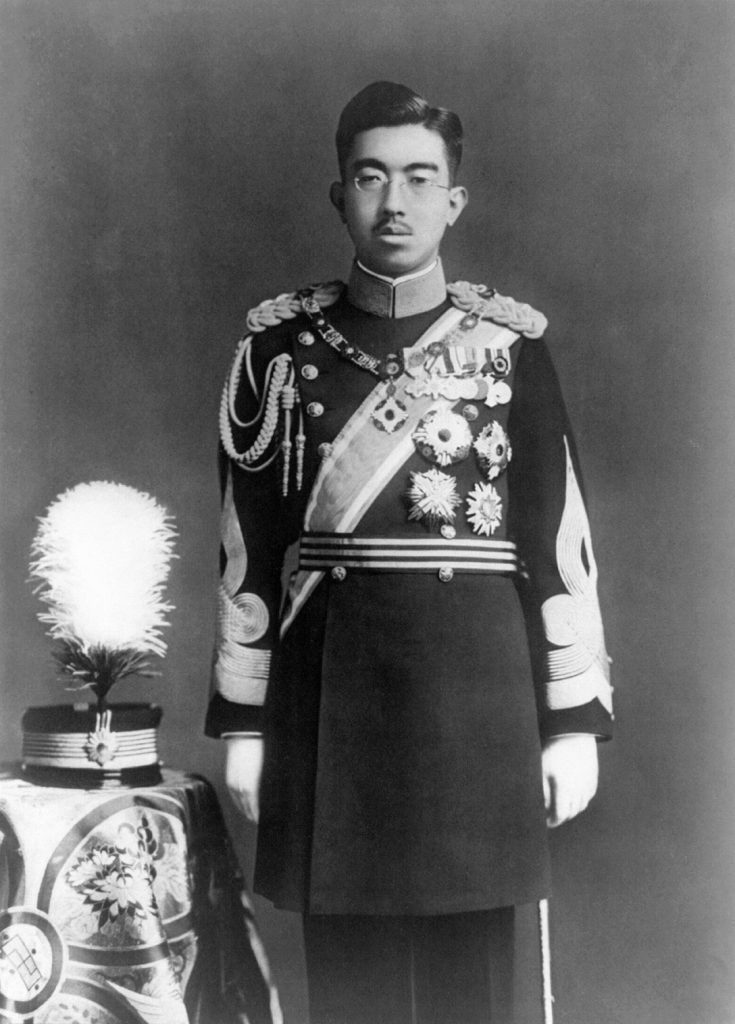

Hirohito (1901-1989), known posthumously as Emperor Shōwa, was emperor of Japan during World War II and is Japan’s longest-serving monarch in history.

BACKGROUND

Hirohito was born in Tokyo during the Meiji Period to the son of the reigning emperor. His father ascended the throne in 1912. In 1921, Hirohito visited Europe; a first for a crown prince of Japan. He was married in 1924 and became emperor in 1926 (after serving as regent for his father).

The emperor was regarded by many as a divine figure according to the traditions of Buddhist and Shinto sects in Japan. In this same tradition, the Japanese nation and race were divinely chosen and protected. The divinity of the emperor was a key component of the concept of the “imperial way,” or kodo, an ideology comparable to manifest destiny in the United States. Kodo promoted subordination of individual citizens to the state and encouraged imperialist expansion. Hirohito’s government advocated this philosophy throughout the period leading up to World War II and this ideology was pervasive throughout society including government and education.

Hirohito presided over the invasion of China, the bombing of Pearl Harbor, and eventually, the Japanese surrender to the Allies. Many historical sources have portrayed Hirohito as powerless. Often these sorces characterized the emperor as constrained by military advisers that were making all the decisions. Some sources have even portrayed him as pacifist. Hirohito was not tried for war crimes, as many members of the Japanese government were. Some leaders of the occupying Allied forces went to great lengths to corroborate his innocence because they believed that preserving the emperor’s office would be useful for carrying out governmental change.

THE DEBATE OVER HIS ROLE

But a growing number of scholars, including Herbert P. Bix in his Pulitzer Prize-winning biography, have said that Hirohito wielded more power than he was given credit for by these types of sources. Scholars who back this alternative narrative attribute the public perception that he was powerless to a concerted effort in Japan to exonerate the emperor. This group of scholars believe that there was an advantage to portraying Hirohito as not responsible for the state’s actions at the end of the war. There are clear historical instances, however, where Hirohito decisively exercised his power. In one instance, in 1936, he moved swiftly to put down a coup among Japanese military leaders. When Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe stepped down in 1941, Hirohito rejected Konoe’s nomination for a replacement. This cleared the way for the elevation of the hawkish and dictatorial Hideki Tojo.

Bix and other authors fault Hirohito for some of the more egregious crimes committed by the Japanese military. The emperor’s office signed off on uses of chemical weapons during the war in China. They posit that Hirohito also knew about the mistreatment of prisoners of war and about the murder of civilians in Nanking, but did not try to stop these war crimes or punish military leaders despite his ability to do so. These cases fit a larger pattern of blame being place upon Hirohito’s inaction.

This inaction persisted even where action could have prevented war. The invasion of Manchuria started without orders from Tokyo, but Hirohito acquiesced after being assured that the military could succeed in expanding his empire. Before the war with the US, he underestimated American objections to his foreign policy of formally allying himself with Germany and Italy. He also indicated initial reluctance to go to war, but later confirmed the plan to attack Pearl Harbor despite the objections of some of his advisers. He increased his control over military affairs in the lead-up to Pearl Harbor and attended the Conference of Military Councillors (which was unusual). Additonally he asked for more details on the plans for attack. According to an aide, he showed visible joy at the news of the success of the surprise attacks.

THE SURRENDER DECISION

Hirohito first becomes relevant to the history of the Manhattan Project when he approved of the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7th, 1941. America’s official declaration of war against the Axis accelerated the research effort towards creating an atomic weapon. Additionally, the attack on Pearl Harbor was later used as part of President Truman’s rationale for using nuclear weapons against Japan. Some historians point to evidence that Emperor Hirohito had a chance to end the war earlier when it became clear that Japan could not win. Prince Fumimaro Konoe was the only senior statesman that implored Hirohito to start discussing terms of surrender when the emperor called a meeting of his advisors on February 14, 1945. However, Hirohito did not take Konoe’s advice, maintaining hope through August that the Soviet Union could serve as an intermediary for a negotiated peace. Maintaining the emperor’s office was also a key concern of many other Japanese officials, which caused them to reject demands for unconditional surrender, including the Potsdam Declaration.

Hirohito is generally considered to not have had a very “hands on” role in commanding Japan’s military, despite his ability to order a surrender. This, along with the idea that the Japanese people would be too demoralized by the complete removal of their emperor, is why Hirohito was not tried for war crimes in the same manner as Prime Minister Hideki Tojo after surrender. Because of this, Hirohito’s next significant connection to the history of the Manhattan Project came at the end of the war when surrender began to be discussed later on in 1945.

Hirohito learned of the nuclear attack on Hiroshima at 7:50 pm, local time, on August 6, 1945; approximately twelve hours after it had taken place. Two days later, the emperor admitted that the war could not continue. However, neither the emperor nor the Japanese Cabinet were willing to accept unconditional surrender at that time. On August 9th, the second bomb was dropped on Nagasaki and the Soviet Union began its invasion of Japanese occupied territory and the next day, the emperor’s cabinet drafted an “Imperial Rescript ending the War.” On August 12th, Hirohito declared his intention to accept the Potsdam Declaration to the imperial family.

However, this acceptance of the Potsdam Declaration was not yet officially recognized as the end of the war. Cabinet officials continued to debate conditions of surrender, including how best to preserve imperial power and status. Additionally, during this period after Hirohito’s acceptance of the need to surrender but before its official declaration to the Allied forces, there was an unsuccessful attempted coup by a group who wanted to continue the war. Hirohito’s decision was final, however, and his loss of faith in the war effort forced the hands of both politicians and military men who might have prolonged the fighting.

Hirohito announced his surrender to the Japanese people in an historic radio broadcast. This broadcast was the first time that a Japanese emperor had ever addressed the nation in such a manner. Delivered in formal and elaborate form of Japanese, the “Jewel Voice Broadcast” was notable both for what Hirohito did not say―he never used the word “surrender”―and for what he did say. Emperor Hirohito continued to justify Japan’s aggression during the war, but also put forth a new national mission: “To strive for the common prosperity and happiness of all nations as well as the security and well-being of our subjects.” This new mission was very different from the traditional imperial ideologies of Hakko Ichiu and Kodo, which the International Military Tribunal for the Far East in 1948 sites as, “a constitutional rallying-point, and an appeal to the patriotism of the Japanese people” to support imperialist and militarist policies.

The Jewel Voice Broadcast also addressed the existance of “a new and most cruel bomb, the power of which to damage is indeed incalculable.” However, historians continue to debate how much the bomb actually influenced Japan’s decision to surrender. Herbert P. Bix, the author of the Pulitzer Prize winning book Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan, does not dispute the impact of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, but he emphasizes Japanese leaders’ fears of a populist uprising. Others, including Tsuyoshi Hasegawa, have argued that the Soviet invasion was more influential in the decision to surrender than the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The Soviet invasion destroyed Hirohito’s last hope of a negotiated peace, although, unbeknownst to him, the Soviets had been planning this invasion for months.

AFTER THE WAR AND LATER LIFE

In the immediate aftermath of the war, Hirohito renounced the divinity of the emperor and signed a new constitution drafted by the occupying US forces. This new constitution reduced the emperor’s power to that of a figurehead. Hirohito visited Hiroshima in 1947 and continued to publicly mourn the deaths that took place during the atomic attacks throughout his life. He also expressed some contrition for his role in the war. In 1971, Emperor Hirohito expressed that there were parts of the war that he felt “personally sorry for.”

After the war, Hirohito became more open than any emperor had been before. He regularly appeared in public and made details of his life publicly available. He visited the United States in 1975, meeting with President Ford and placing a wreath at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. Hirohito pursued a life-long interest of his by conducting research in marine biology. The emperor died in 1989 at the Imperial Palace and was succeeded by his son Akihito. In Japan, the emperor takes the name of his era once he dies. The name for his era was chosen early on in his reign and now Hirohito is posthumously referred to as “Shōwa.”