John Cairncross (1913-1995) was a British literary scholar, civil servant, and Soviet atomic spy. In the 1990s, Cairncross was identified as the “fifth man” in the Cambridge spy ring, which consisted of four other Soviet double agents: Anthony Blunt, Guy Burgess, Donald Maclean, and Kim Philby.

After joining the Foreign Service in 1936, he was recruited by James Klugmann, an influential communist at Cambridge and Soviet liaison, to become a Soviet spy. Following his move to the Treasury in 1938, he transferred once more in 1940 to the Cabinet Office, where he became the private secretary of Sir Maurice Hankey, the Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster.

In his oral history on the Atomic Heritage Foundation’s Voices of the Manhattan Project website, historian John Earl Haynes notes that Sir Hankey was also a part of the committee that supervised the British atomic program. According to Haynes, this would have given Cairncross “access to all the reports that were coming to Hankey’s office” and allow him to “pass them on to the Soviets.”

Besides possibly passing on information from the British scientists’ MAUD Report, Cairncross also provided Moscow with the list of American scientists, who came to England “to meet with the senior scientists of the British atomic program.” This list of names would later be given to the American NKVD (forerunner to the KGB) station in New York, in order to try to recruit these individuals to become Soviet agents.

Early Years

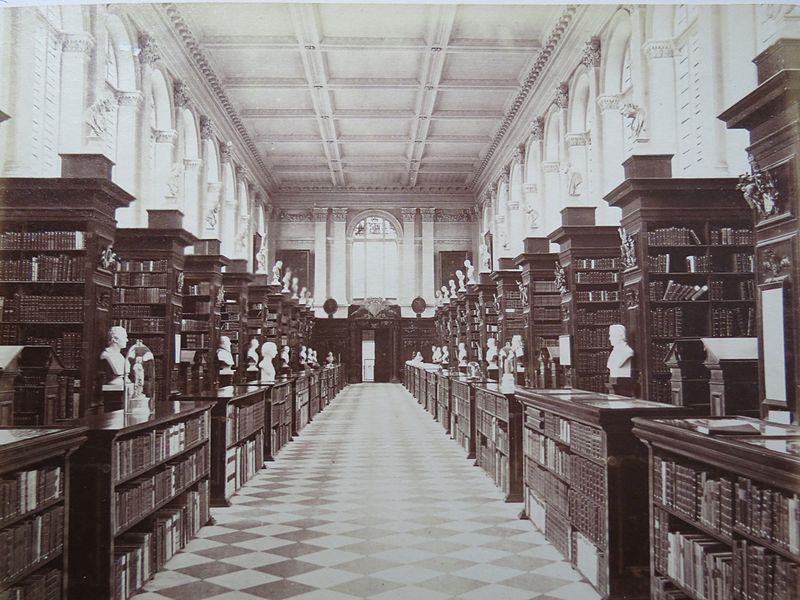

John Cairncross was born on July 25, 1913, in Lesmahagow, Scotland. He was the son of an ironmonger and a school teacher. In 1933, he graduated from the University of Glasgow in 1933 with degrees in German and French. Cairncross continued his language pursuits by studying modern languages at Sorbonne in Paris and Trinity College in Cambridge Univesity.

Later Years

During World War II, Cairncross was recruited by the British armed services to serve as a German translator at Bletchley Park. He worked in Hut 3 of the ENIGMA/Ultra Project, where he helped decode German military communications for the army and intelligence services.

While at Bletchley Park, Cairncross supposedly provided decrypted German communications to the Soviets. Most notably, he alerted the Soviets about German army movements on the Eastern Front, which helped the Soviet army prepare for the German tank-offensive at the Battle of Kursk (July-August 1943). For this crucial information, Cairncross was awarded the Order of the Red Banner, a Soviet military decoration.

In 1944, he was transferred to MI6. The following year, he returned to the Treasury. After World War II, it is believed that Cairncross provided the Soviets with plans about the formation of the new NATO alliance.

After Burgess and Maclean fled England to escape investigation in 1951, handwritten notes from Burgess’ home were found and linked to Cairncross. He was then interrogated by MI5. While he denied being a Soviet spy, he agreed to resign from Civil Service. Following his resignation, he moved to the United States to pursue becoming a literary scholar. While in the U.S., he taught at Northwestern University and Case Western Reserve University.

Following Philby’s defection to the Soviet Union in 1964, Cairncross was again interrogated by MI5 and he confessed to being a Soviet spy. In exchange for providing information about Soviet personnel and other matters, he was not prosecuted and his involvement was kept silent. In the 1990s, Cairncross was identified as the “fifth man” in the Cambridge spy ring by former Soviet intelligence officers.

One of these officers was Yuri Modin, who in 1991 wrote about Cairncross’ role. Although Cairncross denied sharing any information that hurt Britain, Modin claimed that Cairncross did provide information about the progress of American and British scientists in engineering an atomic bomb.

After being revealed as the “fifth man,” Cairncross returned to England and began working on his memoirs, The Enigma Spy (1997), which were published posthumously. At the age of eighty-two years old, John Cairncross died of a stroke on October 8, 1995

For more information about John Cairncross, please see the following references:

- Britannica biography of Cairncross

- The New York Times Obituary for John Cairncross

- The Independent Obituary for John Cairncross

- Profile on John Cairncross that includes primary sources

- John Cairncross’ memoirs, The Enigma Spy (1997)

- Smithsonian Magazine’s article on atomic bomb spies