In 1935, Lise Meitner, Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmanm worked feverishly to sort out all of the substances into which the heaviest of natural elements transmuted under neutron bombardment. By early 1938, they had identified no fewer than ten different half-life activities. At the same time, Irène Joliot-Curie began looking into uranium and came up with results which contradicted those of Hahn and Meitner. The debate raged on.

Not long after, Hahn and Strassmann succeeded in identifying no fewer than sixteen different radioactive substances with varying half-lives. Three of these substances were previously unknown isotopes, and were thought to be isotopes of radium. After several more weeks of tedious work, it seemed that these “radium” isotopes must be barium, element 56, slightly more than half as heavy as uranium.

At first, Hahn and Strassmann could not believe the results. They immediately cabled Lise Meitner, who had fled to Stockholm after her Jewish origins came under question when the Nazis marched into Austria. Her reply seemed to suggest that although the barium discovery appeared to be “impossible”, they should keep an open mind. Hahn and Strassmann continued with further refinements and again cabled Meitner: “Our radium proofs convince us that as chemists we must come to the conclusion that the three carefully-studied isotopes are not radium, but, in fact, barium.”

On January 3, 1939, Otto Frisch returned to Copenhagen from visiting his aunt, Meitner, and informed Niels Bohr of Hahn’s “barium” hypothesis. Bohr was intrigued. That same day, Meitner cabled Hahn again: “I am fairly certain now that you really have a splitting towards barium and I consider it a wonderful result for which I congratulate you and Strassmann very warmly…You now have a wide, and beautiful field of work ahead of you…” What they had succeeded in doing, for the first time, was “splitting” an atom.

To be sure, Hahn and Strassmann’s results needed to be replicated. Using his own lab in Copenhagen, Frisch conducted several experiments with a simple ionization chamber and confirmed Hahn and Strassmann’s results. Over the following weekend, Meitner and Frisch conferred by phone to prepare two papers for Nature, which featured a joint explanation of the reaction and Frisch’s report of the confirming evidence of his experiment. Both reports—”Disintegration of uranium by neutrons: a new type of nuclear reaction” and “Physical evidence for the division of heavy nuclei under neutron bombardment”—used the term “fission” for the first time to describe the reaction.

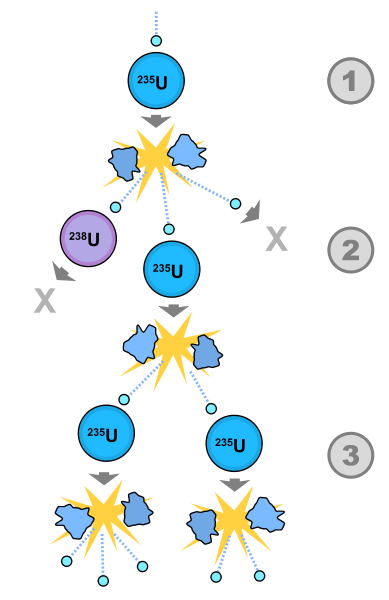

News of Hahn and Strassmann’s discovery spread rapidly. Leo Szilard, having read the Hahn-Strassmann paper, wrote to Lewis Strauss on January 25, 1939: “I feel I ought to let you know of a very sensational new development in nuclear physics. In a recent paper…Hahn reports that he finds when bombarding uranium with neutrons the uranium ‘breaks up’…This is entirely unexpected and exciting news for the average physicist. The department of physics at Princeton, where I have spent the last few days, was like a stirred-up ant heap. Apart from the purely scientific interest there may be another aspect of this discovery, which so far does not seem to have caught the attention of those to whom I spoke. First of all it is obvious that the energy released in this new reaction must be very much higher than all previously known cases…This in itself might make it possible to produce power by means of nuclear energy, but I do not think that this possibility is very exciting, for the cost of investment would probably be too high to make the process worthwhile. I see…possibilities in another direction. These might lead to large-scale production of energy and radioactive elements, unfortunately also perhaps to atomic bombs. This new discovery revives all the hopes and fears in this respect which I had in 1934 and 1935, and which I have as good as abandoned in the course of the past two years.”

News of Hahn and Strassmann’s discovery spread rapidly. Leo Szilard, having read the Hahn-Strassmann paper, wrote to Lewis Strauss on January 25, 1939: “I feel I ought to let you know of a very sensational new development in nuclear physics. In a recent paper…Hahn reports that he finds when bombarding uranium with neutrons the uranium ‘breaks up’…This is entirely unexpected and exciting news for the average physicist. The department of physics at Princeton, where I have spent the last few days, was like a stirred-up ant heap. Apart from the purely scientific interest there may be another aspect of this discovery, which so far does not seem to have caught the attention of those to whom I spoke. First of all it is obvious that the energy released in this new reaction must be very much higher than all previously known cases…This in itself might make it possible to produce power by means of nuclear energy, but I do not think that this possibility is very exciting, for the cost of investment would probably be too high to make the process worthwhile. I see…possibilities in another direction. These might lead to large-scale production of energy and radioactive elements, unfortunately also perhaps to atomic bombs. This new discovery revives all the hopes and fears in this respect which I had in 1934 and 1935, and which I have as good as abandoned in the course of the past two years.”