The 4th episode of “Manhattan” explores Frank Winter’s background as a soldier and scientist. For the first time, the show uses flashbacks. We find out that Winter was a soldier in World War I, for some reason nicknamed “Fat Head” by his comrades. Winter is sent on a mission to collect papers from dead Germans; when he returns, his unit is dead, killed by the gruesome chlorine gas. This glimpse into his past allows the audience to better understand why Winter so closely follows the war’s casualty count, why he’s willing to do anything to do shorten the war – even point a gun at his colleague’s head to convince him to stay on his team.

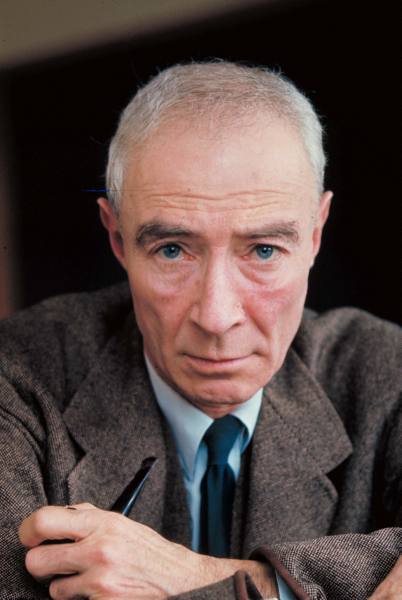

Winter’s fear is underscored by the introduction of a new character, Niels Bohr, venerated by the Los Alamos physicists as “the God of physics.” Having dramatically escaped the Nazis, Bohr is brought to Los Alamos by J. Robert Oppenheimer to consult on the Thin Man bomb. But Bohr is drawn to the implosion program and warmly greets Winter, whom he obviously respects as a person and a physicist.

At the end of this episode, Bohr pointedly asks Winter whether the bomb will be “big enough.” Presumably, Bohr is concerned whether the new weapon will be sufficiently destructive to serve as a real deterrent and effectively end all future world wars, as Winter hopes. Bohr himself seems genuinely skeptical.

In the real Manhattan Project, Bohr and his son Aage shuttled back and forth advising scientists in Los Alamos, Washington, DC and England during the war. However, Bohr became increasingly preoccupied by the legacy of the bomb, how to prevent a nuclear arms race, and other moral questions. We are curious to see whether Bohr will show up again in Los Alamos on the show, and in what context.

“Manhattan” has now portrayed two real scientists in the show: Bohr and Oppenheimer. The actor who played Bohr, although he did a fine job, did not really look like the serious, long-faced Bohr. Daniel London, who played Oppie, does look startlingly like Oppenheimer – except for the eyes. Oppenheimer was famous for his bright blue eyes. In his interview, Dimas Chavez, a young boy at Los Alamos during the project, recalled Oppenheimer’s “majestic blue eyes.” “Manhattan” continues to portray Oppenheimer as brusque with his subordinates, but this episode also highlighted his eloquence in his toast to Bohr. We are looking forward to seeing where Oppenheimer’s storyline goes and which other real scientists the show chooses to introduce. We would love to see Richard Feynman play a prank on somber Frank Winter!

This episode highlights the horror of past war and the threat of future nuclear war. After World War I, the international community banned the use of poison gas in warfare. But, as Niels Bohr explains, discoveries and inventions can have unintended consequences. He mentions Fritz Haber, who won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry and helped direct the German effort to develop poison gas in WWI. Haber’s wife was completely opposed to his chemical warfare work; in 1915, after an argument with him on the subject, she killed herself.

While poison gas was not widely used in World War II (Italy used mustard gas against Ethiopians), a cyanide-based pesticide gas known as Zyclon B was used to kill millions of Jews and other people the Nazis deemed “undesirables” in the concentration and extermination camps of the Holocaust. Ironically, Haber, who worked on the development of the pesticide, was born into a religious Jewish family and much of his extended family was killed in the Holocaust.

As early as April 1944, Bohr recognized that the new weapon “will completely change all future conditions of war.” Like Haber’s work, an atomic bomb is a double-edged sword: it might contribute to ending the current war but also lead to an escalating arms race after the war. While other scientists are focused on getting the job done and ending this war, Bohr is already focused on the very real prospect of a nuclear arms race that will present a “perpetual menace to human security.”

In just four episodes, “Manhattan” has shown a willingness to grapple with the morality of the bomb and its controversial legacy. We are pleased that the show provides several perspectives on the subject, from Winter’s determination to end the war, whatever the cost, to Bohr’s moral issues and concern for the future. We look forward to seeing how this dynamic is played out in the rest of the season.