To accomplish the enormous, complex task of building the world’s first atomic bombs, the U.S. government forged partnerships with major American corporations. Cooperation between the military, scientists, and private industry was especially important in solving one of the Manhattan Project’s most daunting challenges: how to separate fissile uranium-235 from its much more abundant relative, uranium-238.

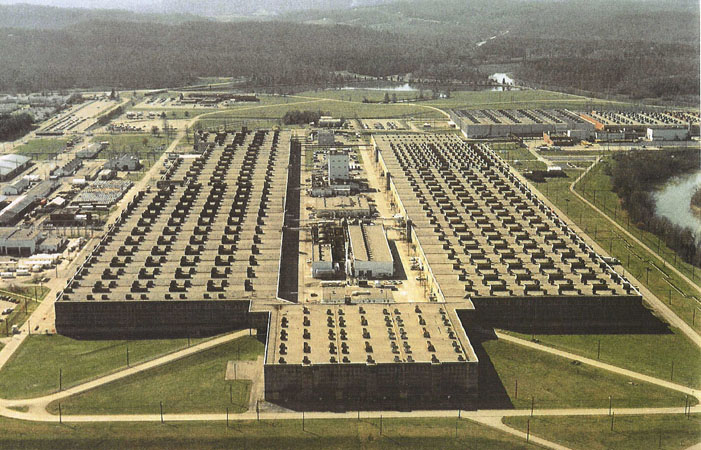

Manhattan Project leader General Leslie Groves authorized the construction of the K-25 plant at Oak Ridge, Tennessee to produce enriched uranium using gaseous diffusion. For gaseous diffusion to succeed, engineers had to construct thousands of large, cylindrical metal containers, or diffusers, to enclose the barrier material that separated the uranium isotopes. To build the diffusers, General Groves turned to a manufacturing powerhouse: the Chrysler Corporation.

On April 2, 1943, Groves and his top aides met with Chrysler president K.T. Keller in Detroit. The company agreed to take on the project even without knowing what the barrier material would be. “To laymen, the thing [the Manhattan Project] sounded almost incredibly fantastic,” Chrysler’s 1947 official history of its Manhattan Project work, appropriately titled Secret, recounted. “But if the United States Government thought it practicable, this, Mr. Keller said, was all that the Corporation needed to know.” Chrysler was awarded a $75 million contract.

Chrysler established offices at 1525 Woodward Avenue in downtown Detroit to oversee the top-secret “Project X-100.” Only the company’s highest executives knew the true nature of the project. Dr. Carl Heussner, director of Chrysler’s plating laboratory, was tasked with designing plating that would prevent the uranium hexafluoride gas used in the gaseous diffusion process from corroding the diffusers.

Using solid nickel, a metal that uranium hexafluoride does not corrode, for the diffusers at K-25 would have exhausted the entire U.S. nickel supply.Instead, Chrysler proposed to use thin, electroplated nickel on steel, which would use approximately 1,000 times less nickel. The Kellex Corporation, responsible for building K-25, and the Columbia University scientists that had developed gaseous diffusion were skeptical that the plan would work. “I asked them why we could not nickel plate it,” Keller remembered. “And they told me it could not be done, that they had already spent one hundred thousand dollars.”

Chrysler went ahead anyway. Heussner was able to produce corrosion-resistant plating within two months. Keller recalled hearing the news from Heussner: “He showed me the tank…He said he had it done and he thought it was all right. I went down and looked at it with him and he had a broad smile on his face.”

Chrysler sent a sample to Kellex. Several weeks later, laboratories confirmed that the nickel plate would indeed work. The next challenge was to find a place to assemble and plate the diffusers, which required a massive amount of space – more than 500,000 square feet. Chrysler revamped its entire Lynch Road factory in Detroit to manufacture the diffusers, which included installing a special air-conditioning and air filtration system to ensure that other materials did not contaminate the nickel.

Keller described Chrysler’s task at Lynch Road: “Take the raw cylinders, machine them, plate them, put in the heads, put in the barrier tubes, seal them tight on the ends, put in the end pieces, weld it all together, test it for leaks.” This process employed several thousand workers and required exacting detail, including the precise drilling of some 50 million holes on the end pieces.

By the end of the war, the company had delivered a thousand carloads, and more than 3,500 diffusers, to Oak Ridge. Chrysler’s work was instrumental in producing enough enriched uranium to build the “Little Boy” uranium bomb, which was dropped on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. These diffusers would successfully operate at K-25 until the 1980s.

Secret quotes from a letter of thanks General Groves sent to President Keller: “No one outside the K-25 portion of the project can ever know how much we depended on you and how well you performed. Those of us who do know will never forget how important your work was and how well you did it.”

Chrysler’s work exemplifies how cooperation between the government and private industry was essential to the development of the atomic bombs. The development of new technologies and the growth of the defense industry are legacies of the Manhattan Project that continue to influence our world today.

You can find more information about Chrysler’s role in the Manhattan Project on AHF’s Voices of the Manhattan Project website, which includes two interviews with Keller.