“It made a difference. Not an enormous difference, but it made a difference,” Philip Abelson remembered.

Abelson was describing the S-50 Plant, which used the thermal diffusion method he pioneered to separate uranium isotopes. S-50 was one of the Manhattan Project production sites at Oak Ridge, Tennessee. Together with the K-25 and Y-12 uranium enrichment plants, S-50 produced the enriched uranium for the Little Boy atomic bomb, which the U.S. dropped on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. According to Abelson, S-50 helped shorten World War II by seven days.

The Manhattan Project was just one part of Abelson’s diverse scientific career. From his research at the University of California, Berkeley before the war to his years at the Carnegie Institution of Washington, Abelson made many contributions to 20th-century American science.

Lawrence & Oppenheimer

Abelson was born in Tacoma, Washington in 1913. After graduating with both a Bachelor’s degree in chemistry and a Master’s degree in physics from Washington State University, Abelson began a fellowship as a teaching assistant at the University of California, Berkeley in 1935. There he worked with Ernest Lawrence on his cyclotron. As soon as he arrived in Berkeley, Lawrence put him to work right away.

“Right then and there, he asked me to paint the cyclotron,” Abelson recalled. “It had been a dirty black, and he wanted it a battleship gray. He had the paint there and the brush, so I started to paint. Pretty soon, all of a sudden, I had a companion in painting. Ernest Lawrence was painting too. Between the two of us, we painted the cyclotron.”

As a graduate student in a team of postdocs working in the famous cyclotron laboratory, Abelson soon became consigned to leak-detecting duty. Constructed in part with beeswax and rosin, the cyclotron often sprang leaks when the magnetic fields were adjusted.

In one instance Abelson remembered being alone with the cyclotron when J. Robert Oppenheimer, a professor at Berkeley at the time, entered the laboratory: “He looks around, eyeballs the place. He sees that I’m the only person there, and of course, being a poor graduate student with no theoretical background, I was a nonentity. So he didn’t waste any time on me.

“Oppenheimer moved over to the backboard to write something to the effect: ‘Cocktail party to benefit Loyalists’ [the Loyalist side in the Spanish Civil War]” and then left.”

Half an hour later, Lawrence entered the lab to check on Abelson and the cyclotron. Abelson recalled his reaction:

Half an hour later, Lawrence entered the lab to check on Abelson and the cyclotron. Abelson recalled his reaction:

“Lawrence looked around to see what was going on and his eyes fell on the blackboard. Lawrence had the habit that when something really agitated him, he would clench his jaws… He kind of stood there for a moment. Then he slowly walked over to the blackboard and he took an eraser and erased off what Oppenheimer had written.”

Abelson believed this incident was a factor in Oppenheimer and Lawrence’s eventual falling-out. “In my mind this was the beginning of a split,” he stated. Knowing Lawrence to be “a very proud man,” Abelson hypothesized that Lawrence perceived Oppenheimer to have “invaded his domain and was inciting his students to do something that he did not approve of.”

In addition to these men, Abelson also interacted with other future Manhattan Project scientists at Berkeley, such as Chien-Shiung Wu. He remembered taking the same preliminary exam:

“I had the misfortune that there was a young Chinese woman [Chien-Shiung Wu] who took the exam the morning that I was to be examined in the afternoon. Wu was a brilliant scholar and passed with flying colors. That afternoon, by contrast, I was practically illiterate. But they didn’t flunk me. Lawrence was a big man on campus and it wouldn’t have been diplomatically feasible to flunk that guy.”

From the Naval Research Laboratory to Oak Ridge

In 1939, after he received his Ph.D. in nuclear physics from Berkeley, Abelson moved to Washington, D.C. There he worked at the Geophysical Laboratory at the Carnegie Institute of Washington. In 1940, he and Edwin McMillan co-discovered the radioactive element neptunium.

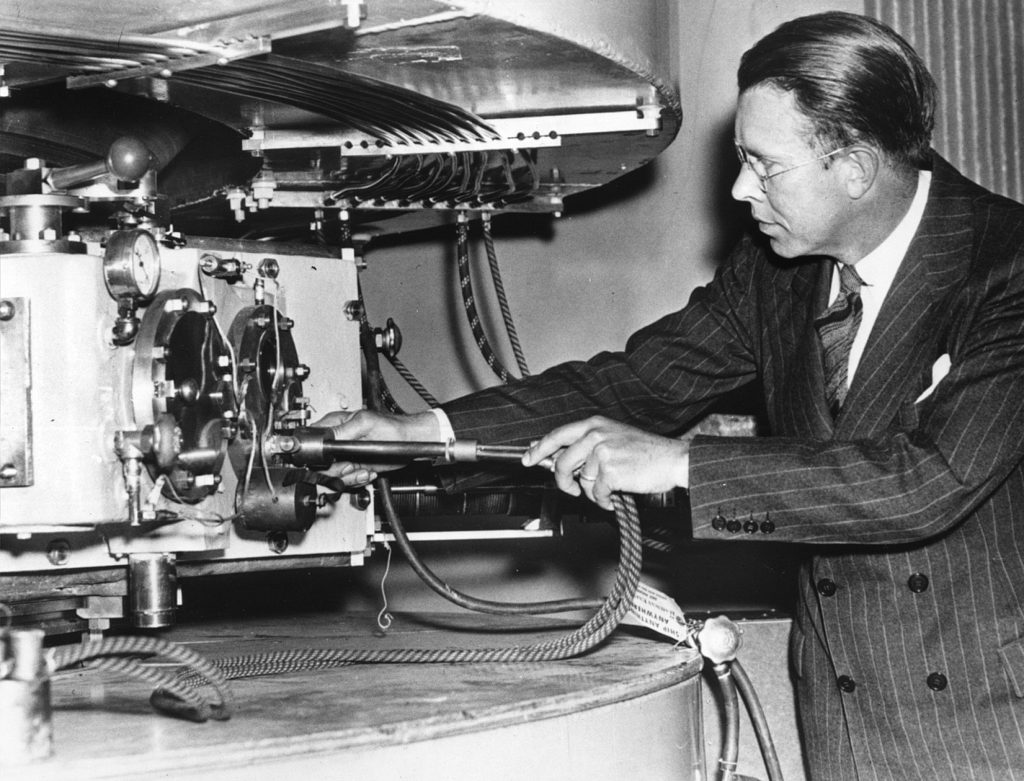

That same year, Abelson began to develop liquid thermal diffusion, a new method to separate uranium isotopes, at the Bureau of Standards. The U.S. Navy was interested in producing nuclear-powered submarines and in 1941 recruited him to work on thermal diffusion at the Naval Research Laboratory. Eventually, Abelson received authorization to build a pilot plant in the Philadelphia Navy Yard. With the U.S. now embroiled in World War II, he worked relentlessly: “I was at it more than twelve hours a day, seven days a week. I wouldn’t go home to bed but would just sleep right there.”

In 1944, aware of the difficulties the Manhattan Project was experiencing with the gaseous diffusion process, Abelson informed J. Robert Oppenheimer about the progress he had made using thermal diffusion. In response, “I got word one day that I was to go to the Warner Theater and go to the balcony at 8 o’clock,” Abelson remembered. “I would be approached by a man who would identify himself and I was to have a one-page summary of the liquid thermal diffusion project.”

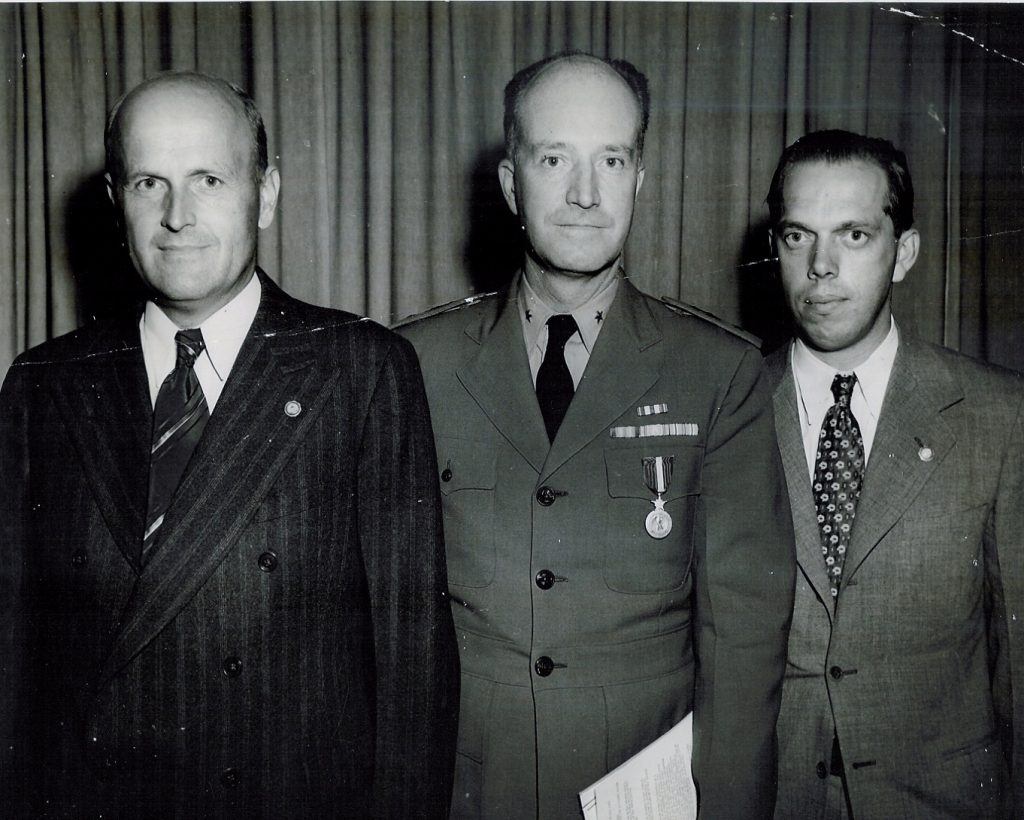

This man was Captain Willliam “Deak” Parsons, head of the Ordnance Division at Los Alamos. Shortly after their meeting, General Leslie Groves ordered that a thermal diffusion plant be built at Oak Ridge. Abelson divided his time between Philadelphia and Oak Ridge to oversee its construction.

In an impressive 69 days, the S-50 plant was completed, with 2,100 columns that all had perfectly round copper tubing inside nickel tubes. The distance between the inner and outer tubes had to be precisely 0.025 centimeters in order for the separation of the isotopes to work.

“It was a really a remarkably fast thing to start from nothing and to do it during wartime,” Abelson reflected. “I certainly would agree that a large component in achieving this fast construction had to be General Groves…He really drove these people to get things constructed, sometimes by stepping on people’s toes or hurting feelings, but the job was always done.”

After being slightly enriched (1-2%) at the S-50 plant, uranium was then fed into the K-25 gaseous diffusion plant and then the Y-12 electromagnetic separation plant. This serial approach ensured enough uranium would be produced for the Little Boy atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima.

Looking back on the Manhattan Project, Abelson said the urgency of the war drove them to complete projects ten times faster than in peacetime. “When people know, ‘Here is the objective and this is what needs to be accomplished,’ they put their minds to it. There’s a lesson to be learned about what happens when people are dedicated to achieving an end, and where there’s teamwork to do it.”

Postwar Work

In the years following the war, Abelson began exploring biology and geology and published an important work on E. coli in 1955. In 1962, he became the editor of the journal Science, where he published his insightful editorials for 23 years. He also served as the director of the Geophysics Laboratory at the Carnegie Institution of Washington, and then as the Institution’s president. Abelson received seven honorary degrees and held membership in many prestigious scientific societies. In 1987, he received the National Medal of Science.

For younger generations, Abelson advised, “If this country wants to have the best chance of succeeding well in the future, it better see to it that its science and technology is top-notch. Because if anything, there will be more developments.”

Abelson passed away in 2004 at age 91 in Washington, DC.

All quotations are drawn from an interview conducted with Abelson in 2002 by the Atomic Heritage Foundation. To listen to a 1966 interview with Abelson by journalist Stephane Groueff, please click here.