The Atomic Heritage Foundation has more than 500 interviews with Manhattan Project veterans and their families on the “Voices of the Manhattan Project” website. Here are some excerpts in which veterans and their family members recall and reflect on the bombing of Hiroshima.

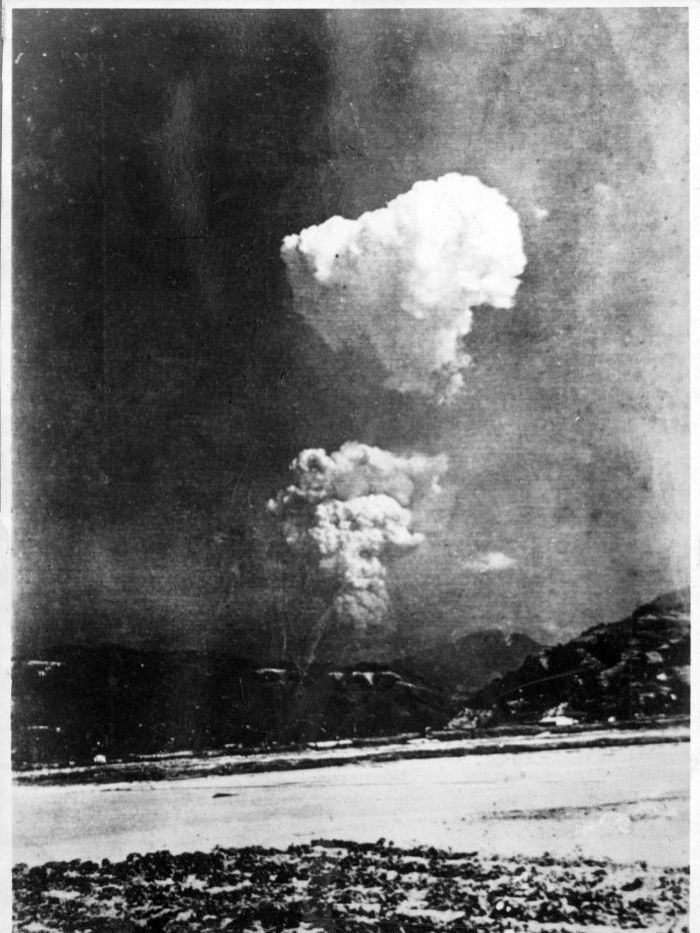

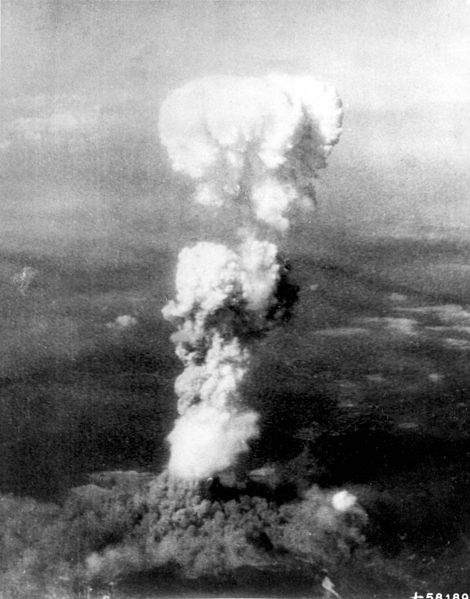

Ray Gallagher, flight engineer, Hiroshima and Nagasaki missions: The morning was a beautiful, bright morning. As we approached, Colonel Tibbets’s bomb doors opened. Major [Tom] Ferebee, who was the bombardier for Colonel Tibbets, let go of the first atomic bomb in history.

We had our goggles on that they had given to us. It was dark. In about a minute, the bomb had exploded. The brightness of the bomb had reached inside of our ship and just lit up the inside of the ship. Once we saw that flash, we looked out. And what all of us saw was something that I don’t think we will ever see, and hope to never see, the rest of our life. The total earth underneath us, the town that was Hiroshima, was completely covered with a huge black cloud. In the center of that cloud was a huge, huge, big ball of fire. At the center, all around it just purple, orange, green, and black. And it was a huge cloud that started its climb up into the sky.

Robert Lewis, co-pilot on the Enola Gay: There was this most awesome sight. The city that had been in front of us, with its dignitaries and bridges and trolleys all outlined, was no longer visible. The city was on fire already and the fire was stretching through the countryside and the tributaries. I expected that if we had been able to pretty well destroy this target, we would have accomplished our mission. I did not expect to see the city disappear.

Paul Tibbets, pilot of the Enola Gay: The whole sky lit up when it exploded. By the time we turned around to look at it, there was nothing but a black boiling mess hanging over the city. It was actually obscuring everything but something on the outskirts. You wouldn’t have known that the city of Hiroshima was there unless you had seen it coming in.

The morality of dropping that bomb was not my business. I was instructed to perform a military mission to drop the bomb. That was the thing that I was going to do the best of my ability.

Russell Gackenbach, navigator on the camera plane, the Necessary Evil: I went to my navigator’s desk, picked up my personal camera, and shot two pictures out of the side of the airplane by the navigator’s table. Because at first [the mushroom cloud] starts off, it’s just 2,000 feet high approximately, straight up. Then she starts blossoming out. You see all sorts of colors in there. By the time we got near the city of Hiroshima, the bomb was higher than we were. The bomb blast was higher than we were. It was just like you see in the photographs. It’s very hard to explain.

Russell Gackenbach, navigator on the camera plane, the Necessary Evil: I went to my navigator’s desk, picked up my personal camera, and shot two pictures out of the side of the airplane by the navigator’s table. Because at first [the mushroom cloud] starts off, it’s just 2,000 feet high approximately, straight up. Then she starts blossoming out. You see all sorts of colors in there. By the time we got near the city of Hiroshima, the bomb was higher than we were. The bomb blast was higher than we were. It was just like you see in the photographs. It’s very hard to explain.

Gwen Groves Robinson, daughter of General Leslie R. Groves: It was on the radio, I think that was sort of where we heard about it. It was a big bomb, and there was my father had done all this work. That is how we found out. You do not believe that, but that is the truth. And my mother was truly astonished.

Ben Bederson, physicist and member of the Special Engineer Detachment: On August 5th, we knew the bomb was going to be dropped that night, that they were going to take off that evening. I woke up the next morning, and we have a radio. I turned on the radio, and that is when I heard about the bomb, because it had already been dropped. Announcers were already announcing it, and Los Alamos was already being spoken about. So the secret was out. Everything was done. Hiroshima was devastated, destroyed. The world had changed while I slept that night in a Quonset hut in Tinian.

General Leslie R. Groves, director of the Manhattan Project: I never had any trouble sleeping. I even went to sleep at the most critical time from my standpoint, which was waiting for news from Hiroshima. After I got the news of the dropping, I wrote a report that I was going to make to General Marshall the next morning. This was about 11:30 at night. Then I gave it to Mrs. O’Leary [his secretary], who wasn’t going to sleep—she couldn’t.

I said, “Now I’m going to sleep in here and when the next message comes in, which will be the message after the plane gets back to Tinian, I want you to wake me up, and we’ll go over this report.”

Roslyn Robinson, driver and worker in the administration office at the Chicago Met Lab: I’m glad I was involved in it, if it was a positive thing. But every time I hear of a story of a Japanese person or their family, and that was in the paper or on TV eventually very often, people whose skin was peeling away, people who had different diseases, then I would feel sort of, should I say, guilty of having been a part of that whole operation. All these innocent people who were going about their work, like I tried to do all my life, and then all of sudden they weren’t there at all.

Roslyn Robinson, driver and worker in the administration office at the Chicago Met Lab: I’m glad I was involved in it, if it was a positive thing. But every time I hear of a story of a Japanese person or their family, and that was in the paper or on TV eventually very often, people whose skin was peeling away, people who had different diseases, then I would feel sort of, should I say, guilty of having been a part of that whole operation. All these innocent people who were going about their work, like I tried to do all my life, and then all of sudden they weren’t there at all.

Jacob Beser, radar countermeasures officer and the only person to be on the strike plane on both the Hiroshima and Nagasaki missions: Eighty-five percent of the survivors within three thousand feet of the explosion suffered some form of radiation disease. This is something that people ask. Didn’t we know, didn’t we anticipate? We did not know the extent. We did anticipate that anybody within a radius of several hundred feet would be hurt badly by radiation, but they would also either be blown to hell or burned. So as a separate entity, and as a prolonged aftereffect, we were a little naïve.

Al Zelver, Japanese language officer in the US Army: Nobody had seen anything like this. I thought, “Well, if you have seen one bombed-out city, you have seen them all,” but that’s not true. When I got to Tokyo, it looked very different from Hiroshima. In Tokyo, the cities were just blocks and blocks of ashes. In the central area, all the buildings were still standing. But in Hiroshima, big reinforced concrete buildings were tipped over on their sides. All the windows were blown out. Everybody inside it, of course, had been obliterated. I am sure that this would be debated and disagreed with by many people, but in my view, it was a war crime. It far exceeded what was needed to get the Japanese to surrender.

Edward Teller, physicist and father of the hydrogen bomb: It is a remarkable thing. I have been asked again and again whether I have regrets. If you had the choice that something simply was in the long term unavoidable should be first done by the United States or by the Nazis or by the Soviets or by someone else, would you have regrets to make sure that we did it first?

Kathleen Maxwell, physicist for Kellex in Jersey City, NJ: I think all of us wondered, “Well, we have done it. We’ve saved one terrible thing [i.e. prevented an invasion of Japan] and done another.” I think, what would have happened to all the men who were in the service at that time? A lot more would have gotten messed up with without the atomic bomb.

Kathleen Maxwell, physicist for Kellex in Jersey City, NJ: I think all of us wondered, “Well, we have done it. We’ve saved one terrible thing [i.e. prevented an invasion of Japan] and done another.” I think, what would have happened to all the men who were in the service at that time? A lot more would have gotten messed up with without the atomic bomb.

Fred Vaslow, physical chemist: It’s been very controversial, “Should we have dropped a bomb? Was it a horrible thing to do?” Yes, it was a horrible thing to do. But this was a time of horrors. There was a firebombing of Tokyo, which killed all those people. There were the horrors of Europe with the Nazis, and the horrors of the Japanese in Nanking. There were any number of horrors, so this was another one of these horrors. To me, this bomb ended the horrors. History won’t tell us what might have happened. All we know is that this bomb was dropped and a few days later the war ended.

Jean Bacher, “computer” at Los Alamos: Just after Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the first group of observers came back to Los Alamos. They were so appalled and just stunned that people would just gather together in the evenings and just talk about it and try to grasp what had happened. I was just absolutely undone. I went home and I could not go to sleep. I just really shook all night. It was such a shock to me. I am sure that there were others that had the same experience. Such a very deep experience, it never leaves you.

Leona Woods Marshall, physicist: In wartime, it was a desperate time. I think we did right and we couldn’t have done differently. When you’re in a war to the death, I don’t think you stand around and say, “Is it right?”

Norman Brown, chemist and member of the Special Engineer Detachment: Most of us at Los Alamos felt that the nuclear weapon should not be used in war first, that it should be demonstrated to the Japanese before it was used. But the powers that be decided that they were going to use this weapon.

Norman Brown, chemist and member of the Special Engineer Detachment: Most of us at Los Alamos felt that the nuclear weapon should not be used in war first, that it should be demonstrated to the Japanese before it was used. But the powers that be decided that they were going to use this weapon.

So the first one went to Hiroshima. Although we were distressed, most of us, at the fact that it had been used, we were, in a sense, relieved that the results of our efforts had finally been used. And relieved that the news of the work at the Manhattan Project was now public, so we felt freer to talk.

We did not really know much about the devastation until long after the bomb had been dropped. Subsequently, when I learned about it, of course, I was devastated. I visited Hiroshima and Nagasaki in the 1990s and went to the memorials. The one in Hiroshima was particularly moving. And what impressed me most about that, besides all the photographs and evidence that we could see on the ground of the devastation, was the fact that the main burden of the exhibits of the museum in Hiroshima was an anti-war message. It was not any resentment toward the United States for having dropped it. It was an anti-war message.

Esequiel Salazar, carpenter and surveyor at Los Alamos: The reaction was mixed. There were people that said, “Oh, they shouldn’t have done it,” and the killing of that many people and everything else. I think that I took a different view, because I was coming of age where I was going to be going to the service. I said, “Well, that saved a lot of American lives. We did what we had to do, because if the war would have lasted longer, we would have lost a lot more people.” That’s what we were feeling we had accomplished.

Mary Kennedy, high school student at Oak Ridge: I was terribly distressed. Thinking of all the dreadful things of the atomic bomb. It was a crucial time in my life. Many years later, I began to recognize that it was a necessity, and it was essential. But at the time, for a young person with high ideals, it was a crushing blow to me. In retrospect, I see so much that I did not see at the time. But it was a painful time for me.

Anthony French, physicist: I would say that I thought the use of the first bomb was justified. I think anybody who had a relative or a friend serving in the Pacific would have been very concerned about what it would take to complete an invasion of Japan.

The Japanese military was certainly no friends of ours. Japan had been very aggressive and therefore any reasonable weapon of war was justified. Once Germany had already been defeated and Japan was the main enemy, the atomic bomb had not been used, I couldn’t see that it would be withheld after that tremendous development work. It would be used most likely on Japan and was very soon.

But I think after the bombing of Hiroshima many people at Los Alamos, including me, were really aghast that another bomb should have been dropped so soon after the first one on Japan. That’s just my personal feeling about it. Japan was not given a chance to assimilate the importance and the nature of what had actually happened at Hiroshima. I didn’t feel that the dropping of a second bomb so soon was reasonable.

Julie Melton, daughter of Project historian David Hawkins: He went to Hiroshima with an official after-the-bomb mission. Sometimes he would talk about it, but I think it was a just searing experience for him. I don’t think any of us who haven’t seen it can imagine what that was like. He was always delighted with the complexities of science and the complexities of life. But sometimes I felt underneath that he was also angry at what had happened, and what was continuing to happen with the buildup of nuclear weapons.

Julie Melton, daughter of Project historian David Hawkins: He went to Hiroshima with an official after-the-bomb mission. Sometimes he would talk about it, but I think it was a just searing experience for him. I don’t think any of us who haven’t seen it can imagine what that was like. He was always delighted with the complexities of science and the complexities of life. But sometimes I felt underneath that he was also angry at what had happened, and what was continuing to happen with the buildup of nuclear weapons.

Jack Widowsky, navigator of the Big Stink, the backup strike plane: We heard on the radio President Truman announcing we had dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima, and the destruction was awesome. We were all charged up for what we did, because we were really—and I say to this day, I am honored and proud that I participated in that. One reason is because we saved thousands of American lives. They had tens of thousands of GIs on Okinawa ready to invade Japan. I have a favorite expression: “If there wasn’t a Pearl Harbor, there wouldn’t have been a Hiroshima.” I think that sums it up. I have no bad feelings that I participated in that, because I feel if the enemy had it, they would have used it.

Val Fitch, Nobel Prize-winning physicist and member of the Special Engineer Detachment: I was a GI and I had many friends in the military. Many of those friends, it turned out, were training for the invasion of Japan in the Philippines. They’ve told me all about this afterwards, thanking me for my participation in the original project. I understand that totally. Somehow people who’ve never been shot at don’t appreciate what it’s all about.

So I would have to say that I was in favor of it. I’m still in favor of it, there’s no doubt. There are any number of people walking around today who wouldn’t be walking around simply because their fathers or their grandfathers would have been killed in Japan, invading that island. I’m convinced of that.

In my own mind, just shutting down that war was in a sense worth it. But that’s not to say we shouldn’t do everything we can to put that genie back in the bottle and keep it there.

Mary Lowe Michel, typist at Oak Ridge: The night that the news broke that the bombs had been dropped, there was joyous occasions in the streets, hugging and kissing and dancing and live music and singing that went on for hours and hours. But it bothered me to know that I, in my very small way, had participated in such a thing, and I sat in my dorm room and cried.