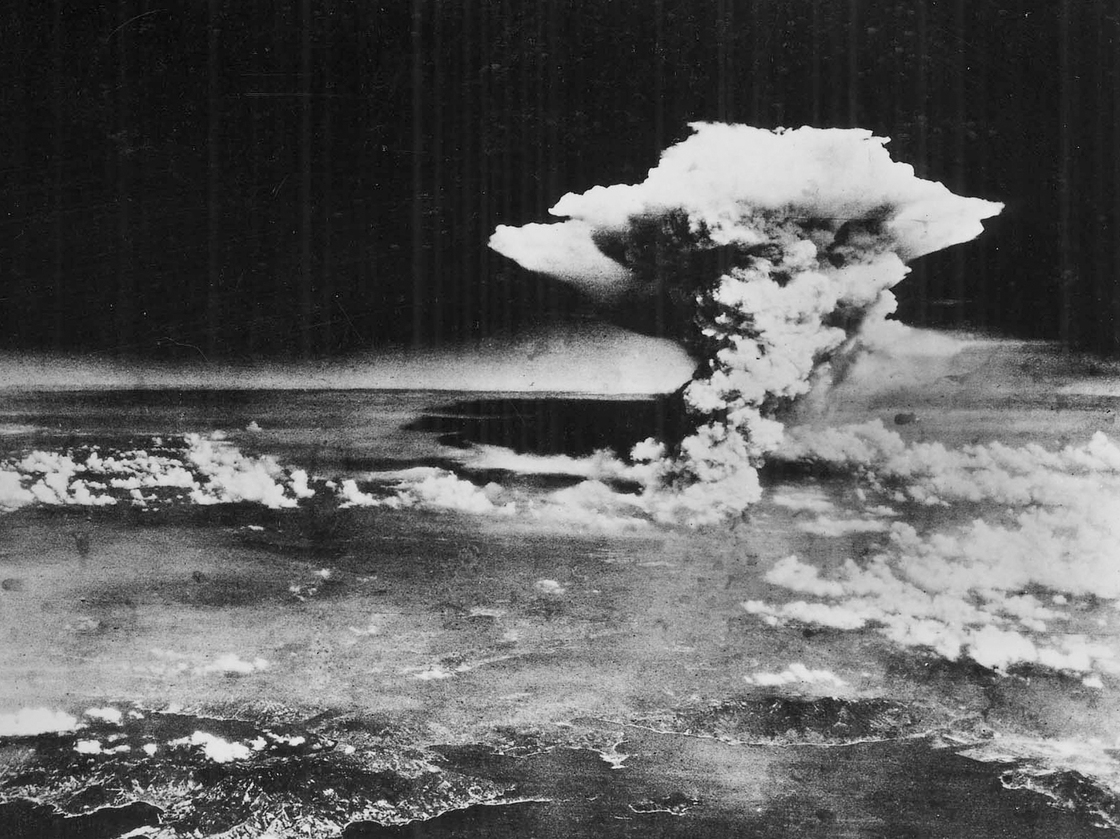

Leo Szilard joined the Manhattan Project in the hopes of developing nuclear weapons before Nazi Germany, but he began to see the possible dangers to peace and international relations posed by the weapons after Germany’s defeat. In July 1945, Szilard circulated a petition to President Truman asking for a peaceful demonstration of the bomb before its use in wartime. Although the petition was signed by 155 Manhattan Project participants at the Met Lab and Oak Ridge, TN, it never reached Truman’s desk, and on August 6, 1945, the Enola Gay dropped the Little Boy atomic bomb on Hiroshima, killing tens of thousands of people. Three days later, on August 9, Bockscar dropped the Fat Man bomb on Nagasaki. On August 15, Emperor Hirohito announced over radio that Japan would surrenader to the Allies.

The Atomic Heritage Foundation’s oral history website, “Voices of the Manhattan Project,” includes more than a hundred interviews with Manhattan Project veterans and their families. Many interviewees recall their memories of the atomic bombing of Japan. Some discuss the moral responsibility of scientists and recall Szilard’s petition. For more oral histories concerning the debate over the bombing, please click here.

John Shachter (Columbia, Oak Ridge): Of course there were a lot of lives saved in Japan. Now, whether we should have tried the bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, or whether we should have demonstrated it offshore in the ocean where they could have watched it, which might have been as convincing. You know, that’s the controversy that’s still going on.

I’ve since met a lot of people in the Navy and Army that would have gone to Japan had the war lasted, and there’s no question in their mind that they were pleased to have the war end that way. And I wouldn’t be surprised if it saved a lot of lives, because an invasion of Japan would have been extremely costly on both sides, and would have dwarfed the deaths and casualties in Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Lilli Hornig (Los Alamos): I remember the petition to not to use the bomb as a weapon came around just after the [Trinity] test. And some of my friends in the same group, whatever it was, X something, were signing it. And I thought about it and I thought that was a good idea. I think many of us had really worked on the bomb with the thought that it might deter Hitler. Once the European war was over with, well, a lot of the people left right away. There wasn’t certainly among the scientists the same gut feeling about using it. And we thought in our innocence—of course it made no difference—but if we petitioned hard enough they might do a demonstration test or something like they later did at Bikini and Enewetak, and invite the Japanese to witness it. But of course the military I think had made the decision well before that they were going to use it no matter what. And so we had very mixed feelings about that.

Lilli Hornig (Los Alamos): I remember the petition to not to use the bomb as a weapon came around just after the [Trinity] test. And some of my friends in the same group, whatever it was, X something, were signing it. And I thought about it and I thought that was a good idea. I think many of us had really worked on the bomb with the thought that it might deter Hitler. Once the European war was over with, well, a lot of the people left right away. There wasn’t certainly among the scientists the same gut feeling about using it. And we thought in our innocence—of course it made no difference—but if we petitioned hard enough they might do a demonstration test or something like they later did at Bikini and Enewetak, and invite the Japanese to witness it. But of course the military I think had made the decision well before that they were going to use it no matter what. And so we had very mixed feelings about that.

Leona Marshall Libby (Hanford): I certainly do recall how I felt when the atomic bombs were used. My brother-in-law was captain of the first minesweeper scheduled into Sasebo Harbor. My brother was a Marine, with a flame thrower, on Okinawa. I’m sure these people would not have lasted in an invasion. It was pretty clear the war would continue, with half a million of our fighting men dead not to say how many Japanese. You know and I know that General (Curtis) LeMay firebombed Tokyo and nobody even mentions the slaughter that happened then. They think Nagasaki and Hiroshima were something compared to the firebombing.

THEY’RE WRONG!

I have no regrets. I think we did right, and we couldn’t have done it differently.

Darragh Nagle (Los Alamos): It was absolutely not the scientists’ decision, and how the scientists would have voted if you’d had an election is not clear to me either. I mean certainly, some of the leading scientists like Ernest Lawrence—yeah, I would expect to be a rather hawkish person, but I was not a close associate of Lawrence in any way.

Darragh Nagle (Los Alamos): It was absolutely not the scientists’ decision, and how the scientists would have voted if you’d had an election is not clear to me either. I mean certainly, some of the leading scientists like Ernest Lawrence—yeah, I would expect to be a rather hawkish person, but I was not a close associate of Lawrence in any way.

Evelyne Litz (Chicago, Los Alamos): I was very solemn. I have to tell you, V-E Day I will never forget at Los Alamos. All the GI’s were out and all the jeeps, tooting horns and running up and down the hills, and people were up celebrating, and in our house suddenly there were like twenty people drinking wine. That was V-E Day. V-E Day, wonderful. The day the bomb was dropped there was no hilarity on the hill. None of our friends got together; we were very solemn.

Graydon Whitman (Oak Ridge): Groves congratulated everybody on the job well done and how the importance of the atom bomb was to the conclusion of the war. It was kind of a controversial thing, which I never realized. I don’t think he ever thought about not using the bomb. You know, there were those who wanted to have a demonstration, show everyone how powerful it was, but his view was it was a weapon and it could bring a conclusion to the war. And that’s what was done.

George Cowan (Columbia, Chicago, Los Alamos): All the scientists that I knew of were for a demonstration. The fact that they were for a demonstration was not transmitted to Truman. He was working as the brand-new President at the time; didn’t know beans, I think, about the bomb project. He turned it all over to the Secretary of War, Stimson, and it was run from the War Department. And they weren’t taking advice about demonstrations. They were going to demonstrate that thing over a Japanese city, and that’s the way it went. So I don’t think the opinions of the scientists mattered one way or the other. They just never were transmitted; they never were taken seriously.

Ben Bederson (Los Alamos, Wendover, Tinian): You have to realize that dropping the bomb saved lives, saved American lives. It killed a lot of people, and you can never understand the horror of that. There is no doubt about that, but war is horrible, and the war was going on, and people were getting killed all the time. The Americans were getting killed, and I guess the first thought was to save American lives. It may have saved Japanese lives too. Who can tell how many Japanese lives would have been lost had there been an invasion of Japan? Probably a lot.