“It was an entirely different world,” Eulalia “Eula” Quintana Newton remembered, describing life in the northern Rio Grande valley before the coming of the Manhattan Project. “Our lives changed entirely.”

The Manhattan Project, the top-secret World War II effort to build an atomic bomb, had a profound impact on the communities of northern New Mexico. The Atomic Heritage Foundation (AHF), a nonprofit in Washington, DC, is dedicated to preserving and interpreting the Manhattan Project history. As part of these efforts, AHF has been collaborating with local partners to collect and publish interviews with residents of northern New Mexico about their experiences.

“We are pleased to share these interviews, the first results of this collaboration, on our ‘Voices of the Manhattan Project’ website,” said Cynthia Kelly, President of AHF. “These resources will be available to visitors to the Manhattan Project National Historical Park, students, educators, museums, journalists and audiences worldwide.”

Earlier this year, AHF interviewed Frances Quintana, Lydia Martinez, and Floy Agnes Lee (right) about their work on the Manhattan Project. These oral histories are now on the “Voices of the Manhattan Project” website along with more than 450 interviews with Manhattan Project participants, family members, and experts.

Earlier this year, AHF interviewed Frances Quintana, Lydia Martinez, and Floy Agnes Lee (right) about their work on the Manhattan Project. These oral histories are now on the “Voices of the Manhattan Project” website along with more than 450 interviews with Manhattan Project participants, family members, and experts.

In addition, AHF has worked with Willie Atencio and David Schiferl to publish a collection of interviews carried out with Manhattan Project participants in 2009. Atencio, a longtime employee of Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL) and the Bradbury Science Museum, worked with retired LANL physicist David Schiferl to capture numerous interviews. Both Atencio and Schiferl volunteered their time to conduct the interviews.

“The Manhattan Project was possibly the most significant project ever undertaken by the United States. The contributions of hundreds of northern New Mexicans—Hispanics, Pueblos, and Anglos—need to be documented,” stated Atencio. “We need to hear from the people who were there.”

“I had already been collecting interviews and stories about Los Alamos for years,” Schiferl said, “and heard some surprising stories about Hispanic life in northern New Mexico. When Willie Atencio asked if I could help, I jumped at the chance. I was struck again and again by the talents and skills that had been underutilized until the Manhattan Project came.”

The Coming of the Manhattan Project

In 1942, Los Alamos was designated as the site for the Manhattan Project’s top-secret scientific laboratory. Native Americans and Hispano homesteaders living on the Pajarito Plateau were forced to leave their lands. Victor and Refugio Romero, who lived in a log cabin seasonally on the plateau, were among the people displaced.

“All of a sudden the Army declared, ‘You can’t come and plant any more over here. We’re going to take over. The government wants your land,’” recalled Rosario Martinez Fiorillo, the Romeros’ granddaughter. Today, visitors to Los Alamos can see the restored Romero Cabin (below, left). The National Park Service has identified the displacement caused by the Manhattan Project as an important theme for the Manhattan Project National Historical Park.

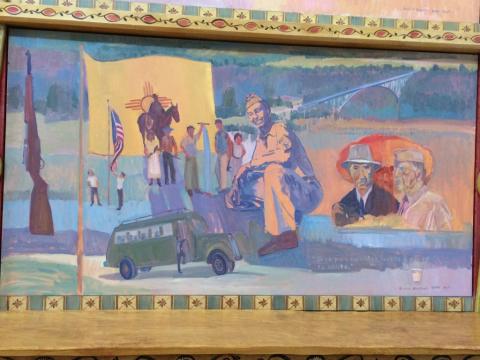

Short of laborers, the Army Corps of Engineers recruited people from neighboring Hispano communities and Pueblos to help build the laboratory and residences. As the interviews document, the Army hired them as construction workers, janitors, housekeepers, technicians, clerks, mess hall staff, mail couriers, maids and other roles. Trucks and green Army buses stopped at the Hispano communities and the Pueblos each morning to pick up workers and take them to jobs on “the Hill,” as Los Alamos was called.

Short of laborers, the Army Corps of Engineers recruited people from neighboring Hispano communities and Pueblos to help build the laboratory and residences. As the interviews document, the Army hired them as construction workers, janitors, housekeepers, technicians, clerks, mess hall staff, mail couriers, maids and other roles. Trucks and green Army buses stopped at the Hispano communities and the Pueblos each morning to pick up workers and take them to jobs on “the Hill,” as Los Alamos was called.

“We all took a part in it,” remembered Esequiel Salazar, who worked as a carpenter and surveyor. “I think it’s important that people realize that the scientists couldn’t do their jobs if it wasn’t for the cement workers that were putting in the slabs and building their laboratories. The janitors, the laborers, the carpenters, everybody took a part in it.”

Interviewees recalled the strict secrecy measures in place at Los Alamos. Floy Agnes Lee explained how the high security made it difficult to see her father, who was from the Santa Clara Pueblo. “They almost decided that I couldn’t work at Los Alamos because my father might get secrets. But finally, they said, ‘Okay, you can go, but your father can’t come visit you. He can’t get near the lab.’ But I could go visit him. That’s the way we did it.”

Relationships between the laboratory and the surrounding communities were not always smooth. Sometimes, when soldiers from Los Alamos came to dances in Española, fights could ensue. “They would come here to Española, and would be chased away or beaten up,” Lydia Martinez recalled.

Despite these incidents, the interviews also describe a basically peaceful coexistence and shared sense of wartime urgency. Some babysitters and housekeepers formed close relationships with the families of the scientists who employed them, often living with them instead of commuting every day. Many Hispano families lived on the Hill and their children went to school there. Esther Vigil, a child during the war, went to school at Los Alamos alongside the children of scientists. “The opportunities we had were far beyond anything that I had seen,” she described. “It was an education in itself.”

After the war ended, Los Alamos continued to employ members of the Hispano communities and Pueblos. Many worked for the Zia Company, which operated the town of Los Alamos for two decades and maintained the technical areas at Los Alamos National Laboratory until 1986. Some Manhattan Project veterans, such as Lydia Martinez, Frances Quintana, and Eula Quintana Newton, spent decades at the laboratory. Today, nearly 38% of LANL employees are Hispanic or Latino.

Legacy

The interviews include various perspectives on the Manhattan Project and its impact on northern New Mexico’s communities. Quintana Newton worked at the laboratory for 53 years, became a group leader, and received a Distinguished Performance Award. “I was treated royally,” she declared. “I felt that I couldn’t have accomplished any more than I did, considering that I did not have a college degree.”

“People in the area were very poor at that time,” Lydia Martinez (right) said. “There was not a lot of work. Most people did farming. But once the lab came in, everybody started prospering. It was a good thing for us living in the Valley. If it had not been for Los Alamos, it would have been hard, because Los Alamos did a lot for people.”

“People in the area were very poor at that time,” Lydia Martinez (right) said. “There was not a lot of work. Most people did farming. But once the lab came in, everybody started prospering. It was a good thing for us living in the Valley. If it had not been for Los Alamos, it would have been hard, because Los Alamos did a lot for people.”

However, not all regarded the laboratory so positively. In addition to concerns about the laboratory’s impact on the environment, some expressed nostalgia about life before the war. Virginia Montoya Archuleta was born in Los Alamos and spent her early childhood there. Her father, Adolfo Montoya, was a homesteader and the head gardener at the Los Alamos Ranch School. “We didn’t want to give up our beautiful life,” she stated. “We had such a great upbringing that we did not want to leave.”

The Atomic Heritage Foundation is grateful to Willie Atencio and David Schiferl for their collaboration in publishing their interviews, and PAC 8 Community Media Center in Los Alamos for digitizing them. The project has also been funded in part by a grant from the Bonderman Southwest Intervention Fund of the National Trust for Historic Preservation, Los Alamos National Bank, and the Kerr Foundation.

On October 12 to 14, 2017, Northern New Mexico College and the Northern Rio Grande National Heritage Area are organizing a conference called Querencia Interrupted: Hispano and Native American Experiences of the Manhattan Project. AHF is pleased to sponsor the event along with the Los Alamos National Bank.

The conference will bring together scholars, writers and artists to reflect on the Manhattan Project and its impact. AHF looks forward to the conference and continuing to work with local partners to capture the intertwined histories of the communities and the Los Alamos laboratory.