Communities of Northern New Mexico

During World War II, residents of the Hispano communities in the Rio Grande Valley and the Pueblos of northern New Mexico were essential to establishing and managing the laboratory and community of the Los Alamos.

Narrator: Historian Jon Hunner describes the often overlooked roles of the Hispano communities and the Pueblos during the Manhattan Project at Los Alamos.

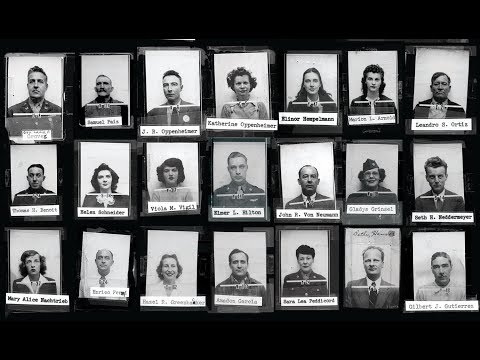

Jon Hunner: When most people think of Los Alamos, they think of the scientists who worked there. Some of them Nobel Prize winners, future Nobel Prize winners. Some of the smartest scientists in the world worked at Los Alamos. But there were other people who made the community go, and one of the key communities that supported Los Alamos were the people from the Valley, from the Española Valley.

Those people were Native Americans, those people were Hispanics whose families sometimes had been in the Valley for generations, maybe even centuries. They would then get on buses every morning and go up the Hill.

Some of them were carpenters who helped build the buildings. Some of them were bus drivers, truck drivers, electricians. Women from San Ildefonso Pueblo were housekeepers and would be assigned to go into different houses and help women, especially who had a lot of children, with their housekeeping duties.

Some people say it was like it a mini United Nations, and that’s not just because of the émigré scientists from Europe who were working there. It was also because of the people from different ethnic groups nearby, from the Española Valley, from the nearby Pueblos who also worked there.

Narrator: Esequiel Salazar was a carpenter and surveyor at Los Alamos. He explains why he thinks the local workforce at Los Alamos should be recognized.

Esequiel Salazar: We should all take credit for that, because we all took a part in it. I think it’s important that people realize that the scientists couldn’t do their jobs if it wasn’t for the cement workers that are putting the slabs and building their laboratories, doing what is necessary to get rid of the contaminated liquids and all the chemicals that were being used.

The janitors, the laborers, the carpenters, everybody took a part in it. I feel that people should get credit for having taken a part, a very important part, in the Manhattan Project.

The Manhattan Project displaced local residents, including the students of the Los Alamos Ranch School and homesteading families.

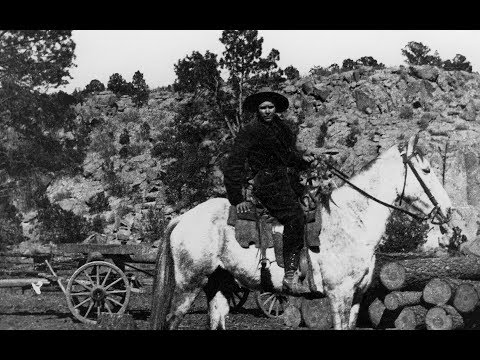

Narrator: When the Manhattan Project took over the Pajarito Plateau in 1942, Hispano homesteaders, including Frances Quintana’s family and Rosario Martinez Fiorillo’s grandparents, were among the people displaced.

Frances Quintana: We had to evacuate, because Los Alamos was taken over. We couldn’t get our belongings that we had there or anything. They didn’t let us. The wagons and buggies and everything that they had. Some of the tools, the machines, they couldn’t get out.

Rosario Martinez Fiorillo: They came and they told him that they had to leave, because they were going to have the soldiers. They called them soldiers or policemen, because they saw them in uniform.

They didn’t have to get out much, but they could not go and plant up there anymore.

They just gave up their land. What else could they do? Because they were frightened by these people in uniform. They came with guns and whatnot, and all of a sudden they came to them and they told them, “Well, you can’t come and plant anymore over here. We’re going to take over. The government wants your land.”

Narrator: Even though the construction of Los Alamos forced people off of their land, large numbers of Hispano and Native workers from the surrounding areas came back to Los Alamos to work on the Manhattan Project. Heather McClenahan describes how families later banded together to win compensation from the government.

Heather McClenahan: Well, in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, the homestead families got together and said, “We really did get a raw deal from the federal government when the Manhattan Project took over our land.” And so Congress, they began working with them, and they set aside ten million dollars for the families of the homesteaders. By the time Congress set aside that money all of the original homesteaders had passed away. And so it was just their descendants who received actually fairly minimal compensation, when you look at thirty-five families and how they had grown and spread over time.

Dimas Chavez recalls the deal his mother made with scientists’ wives, to tutor him in English in exchange for Mexican cooking lessons.

Narrator: Dimas Chavez was only five when his father moved his family to Los Alamos for his job with the Zia Company. Dimas, who spoke only Spanish, struggled to learn English, and he found himself falling behind in school. His mother created a lesson exchange with Lois Bradbury and other scientists’ wives to help him.

Dimas Chavez: I found myself in trouble because as the rest of the class was reading and proceeding, I would translate as much as I could into Spanish and then back into English. I found myself falling way behind. Plus the fact when you are in school with the super students of eminent scientists and so forth who set the bar, I was intimidated, tremendously intimidated.

Well, my mother was a marvelous cook. A lot of the scientists’ wives were basically bored to death, those who weren’t part of the project, and they would just walk around. But they would walk by our house and they would smell these lovely odors coming out of her kitchen.

Unknown to me at that time, they knocked on her door one day and wanted to know, “Why, what is this lovely smell?” and so forth and so on. And Mother, in her way, explained. They said, “We would sure like to know how to cook some of that stuff.”

My mother says, “Well, let’s make a deal.” The deal was, Mother would share with them how to prepare a variety of Mexican dishes, in exchange for tutoring me after school.

The Manhattan Project and the Los Alamos laboratory forever changed the people of the Española Valley. Local residents have a variety of perspectives on “the Lab.” Some believe the Lab has helped the area; others express concern about the laboratory’s impacts on human health and the environment.

Narrator: Oral historian Peter Malmgren has interviewed 150 former Los Alamos workers. He describes their different perspectives about working there and Los Alamos’s impact on the Española Valley.

Peter Malmgren: At the end of each interview, I asked one single question and repeated it. And that is, “if you had your life to live over again, would you go, follow the path again that led you to Los Alamos?” Of the 150, I got 75 saying, “It was fabulous, it was security for my family, education for my family, and I encouraged my children and they have followed in my footsteps.”

The other 75 said, “I would never go near the place again and I would never allow my children to be anywhere near there, because my health was more important than the paycheck.” It was the people who dodged the bullet and were able to live and retire from the Lab without being seriously ill [who] had a lot of positive reasons to praise it. And the other people, a lot of suffering, a lot of loss, a lot of pain.

The Lab has meant life and the Lab has meant death in full measure, both ways.

Narrator: Virginia Montoya Archuleta is the daughter of Adolfo Montoya, who was the head gardener at the Los Alamos Ranch School and owned a homestead. She recalls her idyllic upbringing before the Manhattan Project.

Virginia Montoya Archuleta: We didn’t want to give up that life. That was so beautiful. That was such a great upbringing that we did not want to leave.

Narrator: Lydia Martinez gives her opinion on how the Lab has transformed the area.

Lydia Martinez: People in the area were very poor at that time. There was not a lot of work. Most people did farming. But once the Lab came in, everybody started prospering. You saw everybody improving their homes. There were vehicles, and people buying condos here and there. It was a good thing for us living in the Valley.