Life at Los Alamos

Physicist Edwin McMillan recalls accompanying J. Robert Oppenheimer and General Groves to select a site for the Manhattan Project’s top-secret scientific laboratory.

Narrator: Physicist Edwin McMillan and his wife Elsie once lived in Master Cottage Number One. In 1942, McMillan was working at the Radiation Laboratory at Berkeley, when J. Robert Oppenheimer invited him along on a trip to select a site for the Manhattan Project’s top-secret scientific laboratory.

Edwin McMillan: There were certain requirements for a site. It had to be far from the borders of the United States, and it had to be in an area not close to highly built-up areas, mainly for security reasons. Didn’t want to have the scientists mingling with a lot of townspeople and gossiping about what they were doing.

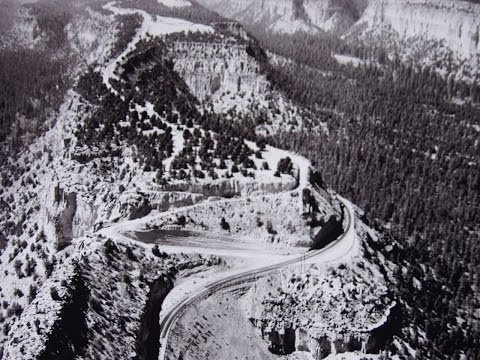

Many places were looked at. Colonel [John H.] Dudley said that he visited most of the small towns in the Southwest. He said he traveled thousands of miles on two-lane roads—one lane for the left wheels and one lane for the right wheels.

Well, this site search headed up. Colonel Dudley had decided, on the basis of the criteria and what he had seen, that the best site was Jemez Springs, New Mexico. So, it was arranged that Oppenheimer and I were to go to Jemez Springs.

Well, soon as [General Leslie] Groves saw it he didn’t like it. There was no argument there. Groves said, “This will never do.”

At that point, Oppenheimer spoke up and said, “If you go on up the canyon, it comes out on top of the mesa and there’s a boys’ school there, which might be a useful site.”

We all got in cars and went up to Los Alamos Ranch School. I remember arriving there. It was late in the afternoon. There was a slight snow falling, just a tiny drizzly type of snow. It was cold. And there were the boys and their masters out on the playing fields in shorts. This is really a place for hardening up the youth.

Soon as Groves saw it, Groves said, “This is it.”

J. Robert Oppenheimer explains why he selected Los Alamos to be the site of the top-secret Manhattan Project weapons laboratory.

Narrator: Los Alamos laboratory director J. Robert Oppenheimer believed that if you had to confine people in an isolated place, you needed to provide them with an inspiring view.

J. Robert Oppenheimer: My feeling was that if you are going to ask people to be essentially confined, you must not put them in the bottom of a canyon. You have to put them on the top of a mesa. It was not a place where you felt locked up.

I will quote Emilio Segrè. When he first came there in April of ’43, he stood by this building that is still there called Fuller Lodge, a sort of hotel. At that time, there was nothing in front of it and you looked out over the desert and to the Sangre de Cristo, which were covered with snow. It was extremely beautiful.

And Segrè said, “We are going to get to hate this view.”

Chemist Richard Baker explains how he was recruited work on a top-secret war project in a secret location – the Manhattan Project at Los Alamos.

Narrator: Richard Baker graduated from Ames College, worked at Ames Laboratory, and then for a company in Chicago as a physical chemist. At age twenty-five, he was recruited to work on the Manhattan Project, but he was not told what he would be doing or where he would be doing it. He remembers J. Robert Oppenheimer showing him a postcard of Ashley Pond with mountains in the distance.

Richard Baker: They couldn’t tell me a great a deal. They just told me that it was a very vital defense project. They told me that it was, from a technical point of view, very challenging, and that they would have no trouble putting me on leave of absence with the company. Pretty much, I joined the project on just what they told me: that it was very important, and would be challenging.

What you did when you started out here like that was, you just put your faith in the people that had talked to you, because you really didn’t know what you were doing or where you were going.

I had never been in New Mexico. The only thing that I recall about that was, Oppenheimer had a picture with him that was taken during the Ranch School days here that showed Ashley Pond over here. It had two swans floating around on it and a canoe. This was taken when the boys were here. Well, it looked pretty good. You could tell by the picture that it was in the mountains, you see.

By the time I arrived here, Ashley Pond—due to construction—had been reduced to just one great big mud hole. No swans. There were no canoes. They were drawing water out of that for construction purposes, you see.

The interesting part of it was, that coming out here through dry New Mexico, I was wondering where all this water of this pond and the swans was!

Elsie McMillan, wife of physicist Edwin McMillan, recalls the intense pressure the scientists at Los Alamos were under.

Narrator: Scientists were forbidden to tell anyone about the project. Elsie McMillan remembers that it was very stressful when her husband was so secretive about the work that so consumed him and his colleagues.

Elsie McMillan: One night I said to my husband, “Why didn’t you tell me you’re making an atomic bomb?”

He said, “My God, where did you learn that?” I don’t think he said, “My, God,” but I will. He said, “You know, you could get me fired.”

But I am very grateful that I knew it was an atomic bomb, because I could better understand when my husband left me, place unknown. When my husband worked all hours of the day and night, when my husband and other husbands looked so drawn, so tired, so worried, I would partially sleep and get up and cook another meal at 3:00 in the morning.

Narrator: Elsie McMillan recalls the tremendous sense of urgency that loomed over the scientists as they worked tirelessly to produce the weapon that might end the war.

Elsie McMillan: Time is going on. Even by that, not quite the end of our first year, they began to realize the emotional strain, the feel of, “You’ve got to get that bomb. You’ve got to get it done! Others are working on it! The Germans are working on it! Hurry, hurry, hurry! This is going to end the war. This is going to save our boys’ lives. This is going to save Japanese boys’ lives. Get that damn bomb done!”

We were tired. We were deathly tired. We had parties, yes, once in a while. I’ve never had so many drinks as there on the few parties. Because you had to let off steam. You had to let off this feeling of your soul, your “God, am I doing right?” You had to, people.

Rose Bethe recounts her son Henry’s battle over spinach with his babysitter, Genia Peierls.

Narrator: Even during the war, Hans Bethe insisted on a two-week summer vacation with his wife Rose. The Bethes’ young son Henry was left in the care of Genia Peierls, wife of physicist Rudolf Peierls.

Rose Bethe: The most amusing story is that we had a friend who had a very vigorous approach to life and quite a loud voice. She was a Russian. When I was going on vacation with Hans without the child, Genia Peierls took over looking after Henry.

Henry moved into her house, and she had full charge of him for two weeks. Now, Genia is a very forceful person and very opinionated. One of the things she thinks is that children should accept.

She began to feed Henry spinach. Henry, of course, knocked it out of her hand first. She wrapped him in a diaper with his arms confined, then started to feed him. He spit it at her. Every time he did one of these things, she would say strongly, “No!”

When I got back and Henry returned to me, and Genia came two days later to see whether I was undoing all the good she had done for Henry, Henry gave one look at her and it was his first word. “No!” he said.

We visited the Peierls later in Birmingham when they had returned to England, and it was no better relation. Henry knew how to behave by then, but he surely didn’t like her.

Vera Kistiakowsky recalls her adventures riding with Sir James Chadwick’s twin daughter, who lived across the street in the Baker House.

Narrator: Vera Kistiakowsky spent two summers in Los Alamos with her father, George Kistiakowsky. She remembers riding horses with the daughters of Sir James Chadwick. Chadwick was a Nobel Prize winner who headed of the British Mission, some 25 scientists from England. The Chadwicks lived across the street from Vera in the Baker House.

Vera Kistiakowsky: The Chadwicks had twin daughters, and they were a couple years older than I was. They liked to ride, and Mrs. Chadwick may have even initiated it. I think the wives at Los Alamos were rather scandalized at the freedom I was given, that I would ride with their daughters. My attitude was that this was a fate worse than death to be condemned to ride with two young ladies, which I did not aspire to be.

Unfortunately, they were used to park riding and didn’t know much about trail riding. By that time, I felt myself to be an expert, so perversely I sort of took the lead in what we did.

Once, when we were taking a shortcut which involved getting off the horses and scrambling up the side of a steep hill, one of the Chadwick sisters unfortunately put her hand where my horse put his hoof and got hurt. That sort of diminished my reliability in the eyes of their family.

However, after riding by myself for a while, the other Chadwick girl said, “Why don’t we go riding together?” So we did—and her horse ran away from her. Of course, it was my fault. Not her fault, but obviously I must be the villain. So that was the end of me riding with the Chadwick girls.