Hanford, Washington, on the beautiful Columbia River, was the site selected for the full-scale plutonium production plant, the B Reactor. Today a popular tourist desination, the Hanford Site proved crucial to the success of the Manhattan Project.

Site Selection

In December 1942, the Army Corps of Engineers worked with DuPont to establish criteria for the selection of a site for plutonium production facilities. The project needed at least 190 square miles of secure space located at least 20 miles from any sizable town and 10 miles from a major highway. Most importantly, the project needed a water supply of at least 25,000 gallons per minute and an electrical supply of at least 100,000 kilowatts.

In late December 1942, three men came on a secret mission that would permanently transform the area. Colonel Franklin T. Matthias and two DuPont engineers had already explored five other possible sites. The Hanford area was the last site they visited. They were quickly convinced that the site was the right one.

The Columbia River provided abundant water and the Grand Coolee Dam, just completed in 1942, could supply electricity. The area was isolated with only about 2,000 residents within 580 square miles.

Displacement

On January 16, 1943, General Leslie Groves officially endorsed Hanford as the proposed plutonium production site. Most residents of the affected area, including those living in Hanford, White Bluffs, and Richland, were given 90 days notice to abandon their homes. Homeowners were compensated based on the appraised value of their homes, excluding the value of improvements, crops, and equipment. Many of the landowners rejected initial offers on their land and took the Army to court seeking more acceptable appraisals. Matthias adopted a strategy of settling out of court to save time, time being a more important commodity than money to the Manhattan Project.

The Native American tribes were also displaced. The Wanapum lost access to their traditional home on the Columbia River, and the tribe resettled in Priest Rapids. Access to their traditional fishing areas was at first restricted and then revoked altogether.

As one chapter of the region’s history ended, a new one began. Within three years, the Columbia Basin became a place of global significance.

DuPont

After the decision to produce plutonium was made, the government needed to draw upon the talent and resources of corporate America to get the job done. General Leslie Groves was familiar with the E. I. du Pont de Nemours & Company, the major chemical and munitions company founded by Eleuthère Irénée du Pont in 1802. DuPont’s manufacturing history and capabilities were impressive.

After the decision to produce plutonium was made, the government needed to draw upon the talent and resources of corporate America to get the job done. General Leslie Groves was familiar with the E. I. du Pont de Nemours & Company, the major chemical and munitions company founded by Eleuthère Irénée du Pont in 1802. DuPont’s manufacturing history and capabilities were impressive.

Despite Groves’ urging, it took a call from President Roosevelt to convince DuPont’s president to sign up for this uncertain venture. Most of all, the company did not want to be branded as “war profiteers” as they had been after World War I for producing gunpowder. This time DuPont insisted that its fee would only be one dollar and all patents would belong to the U.S. government.

DuPont’s managers knew that mass-producing plutonium was to be unlike any challenge they had previously faced. Enrico Fermi’s experimental reactor in Chicago had to be scaled it up thousands of times. Many technical questions, from how to cool the reactor to how to safely extract plutonium from the spent fuel rods, remained unanswered. There was no time for rigorous testing or a long-term pilot-scale facility. DuPont engineers had to use their best judgement to choose an approach and make it work.

Construction

Building the first-of-a-kind production facilities at the Hanford Engineer Works was a formidable management challenge, requiring a massive workforce. During the construction period, 50,000 workers lived in the Hanford Construction Camp. At first they were housed in rows upon rows of tents. By summer 1945, over 1,175 buildings provided housing in 190-person barracks, 20-person huts, trailer camps and service buildings. The camp was the third largest city in Washington.

DuPont attempted to make life for the workers as tolerable as possible. Eight mess halls served fresh baked bread, pies, pastries along with balanced meals. The food was served family style and the workers took about 10 minutes to eat a meal. There was no lingering over a second cup of coffee as there were up to 19,500 diners to serve.

Saturday nights the workers drank beer from the “Patriot Brewery,” constructed specifically for the Hanford workers. Liquor was rationed but there was always some available. Surrounded by barbed wire, men separated from women, the Hanford Camp felt almost like a prison. Many people suffered from depression and homesickness and there were a number of nervous breakdowns.

Construction proceeded at breakneck speed. Each workday was divided into multiple shifts around the clock. Many employees worked overtime and weekends. The complex production facilities and hundreds of support buildings were completed in less than 18 months, a great work of human collaboration.

The Hanford Site

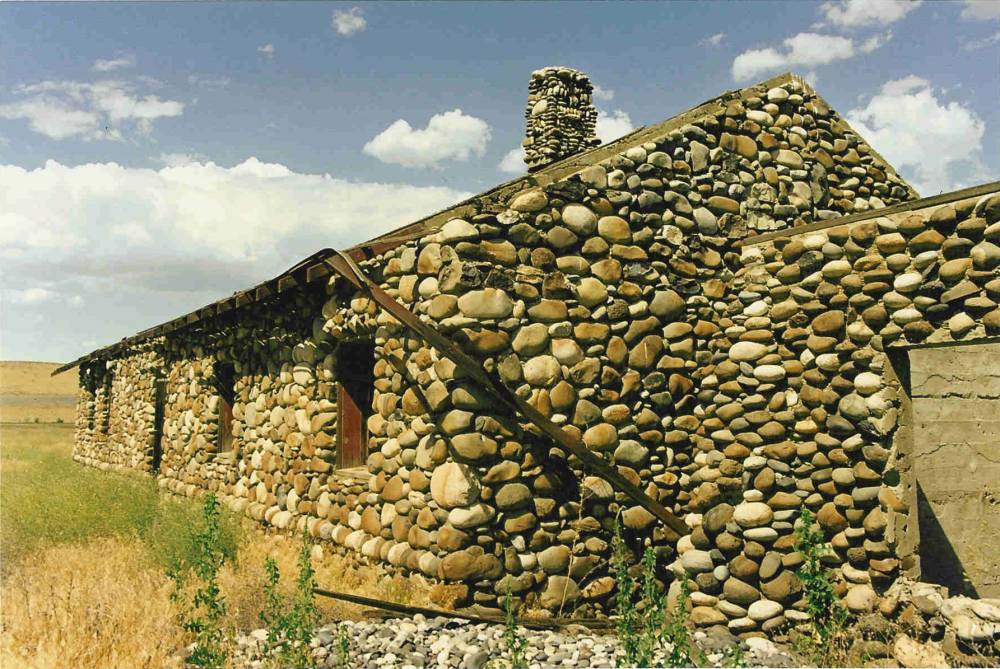

Stretching over 670 square miles, the site was a vast expanse of sage brush and desert. This allowed the different operations to be widely separated and far from the village of Richland.

Stretching over 670 square miles, the site was a vast expanse of sage brush and desert. This allowed the different operations to be widely separated and far from the village of Richland.

In 1943, understanding of the health and environmental effects of different types and levels of radiation exposure was limited. However, precautions were taken to minimize exposures. As part of this, tall stacks were built to help disperse emissions and dilute the gases to safe levels of radioactivity. Monitoring of the atmosphere, environment and workers was conducted to analyze exposure levels and determine if there were any adverse effects.

Producing plutonium at Hanford involved three major operations—fuel fabrication, reactor operations, and chemical separation to extract the plutonium. Closest to Richland in the southeast corner of the site were the fuel fabrication operations in the 300 area.

The reactors were in the 100 area in the northern portion of the site, as far as possible from the town of Richland or about 25 miles away. The chemical separations plants were about 10 miles south of the reactors in the 200 area. Even after 50 years of operations, only ten percent of the site had been used.

Success

Success was achieved when the first irradiated slugs were discharged from the B Reactor on Christmas Day, 1944. The irradiated slugs, after several weeks of storage, went to the chemical separation and concentration facilities. By the end of January 1945, the highly purified plutonium underwent further concentration in the completed chemical isolation building, where remaining impurities were removed successfully.

Los Alamos received its first plutonium on February 2, 1945.