Santa Fe was the first stop for many scientists, engineers, Women’s Army Corps, military police and all others assigned to work on the top-secret project at Los Alamos.

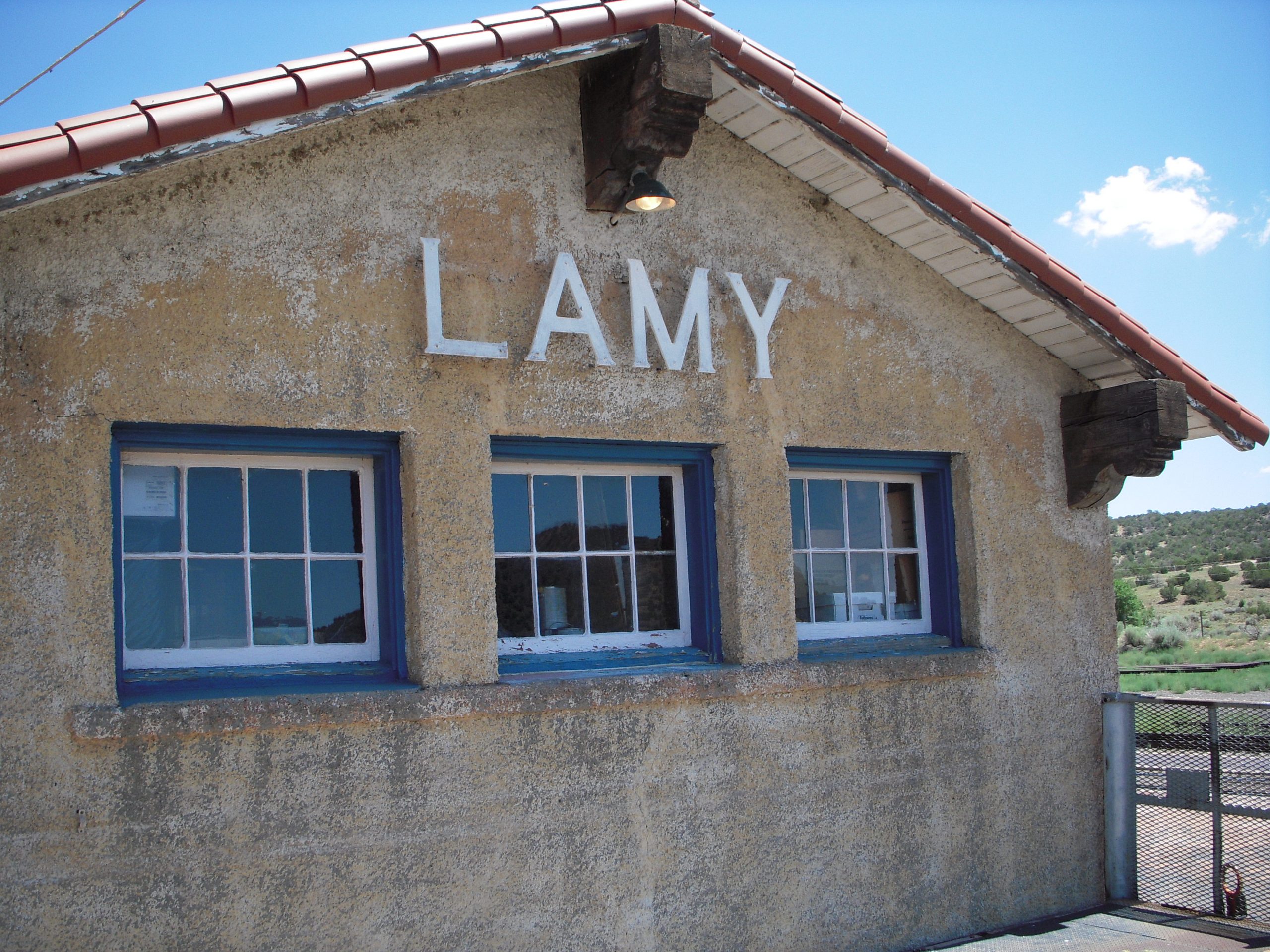

Lamy

Ten miles from Santa Fe, Lamy is the nearest stop on the former Atchinson, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway. Young men and women assigned to work at Los Alamos arrived not knowing where they were or where they were going.

109 East Palace

After arriving in Lamy, the scientists, SEDers, and families were directed to 109 E. Palace Avenue in Santa Fe. The building, constructed as a Spanish hacienda in the 1600s, is located just off the plaza in downtown Santa Fe. During World War II, it was the administrative hub of the Manhattan Project.

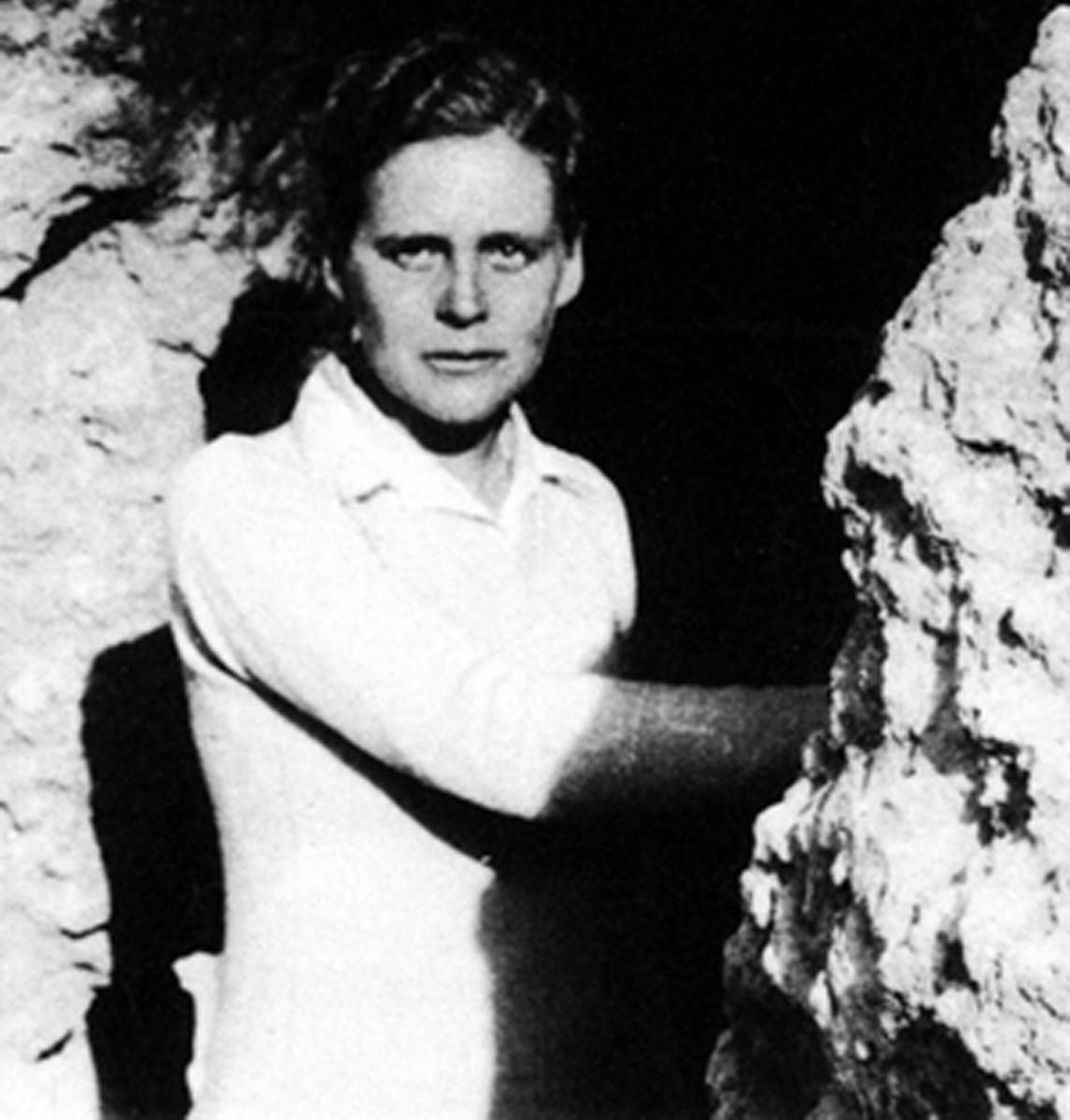

Dorothy Scarritt McKibbin was the first reassuring face the fatigued newcomers saw. At 109 E. Palace, McKibbin informed them that their journey continued another 35 miles along the winding road up to the Pajarito Plateau. In the early months, she dispatched an average of 65 people each day to “the Hill,” as Los Alamos was called. The steady stream of arrivals meant the office was often “bedlam,” as McKibbin described it. She issued passes and IDs and directed newcomers to their homes, received shipments of household items to be distributed to the Hill’s residents, and tended to personal matters as needed.

Dorothy Scarritt McKibbin was the first reassuring face the fatigued newcomers saw. At 109 E. Palace, McKibbin informed them that their journey continued another 35 miles along the winding road up to the Pajarito Plateau. In the early months, she dispatched an average of 65 people each day to “the Hill,” as Los Alamos was called. The steady stream of arrivals meant the office was often “bedlam,” as McKibbin described it. She issued passes and IDs and directed newcomers to their homes, received shipments of household items to be distributed to the Hill’s residents, and tended to personal matters as needed.

McKibbin was the perfect person for her job and quickly became indispensable as the “Gatekeeper” at 109 E. Palace Avenue and a close friend and confidante of Oppenheimer. She had a warm smile, an engaging personality and was reassuringly calm and efficient. In recognition of her contribution, McKibbin was awarded the title of “First Lady” of Los Alamos and declared a Living Treasure of Santa Fe.

La Fonda

Located at 100 East San Francisco Street, La Fonda (Spanish for “inn”) was a favorite watering hole for the scientists and their wives who ventured down from the Hill for a taste of civilization during the Manhattan Project. Fearing that they might loosen up too much and reveal the project’s top-secret goal, covert government agents monitored Los Alamos residents as they unwound here. Santa Feans were trying to figure out what the secret project was at Los Alamos. Worried that they might guess correctly, Oppenheimer asked physicists Bob Serber and John Manley to go to Santa Fe with their wives to spread the rumor that Los Alamos was making electric rockets.

Located at 100 East San Francisco Street, La Fonda (Spanish for “inn”) was a favorite watering hole for the scientists and their wives who ventured down from the Hill for a taste of civilization during the Manhattan Project. Fearing that they might loosen up too much and reveal the project’s top-secret goal, covert government agents monitored Los Alamos residents as they unwound here. Santa Feans were trying to figure out what the secret project was at Los Alamos. Worried that they might guess correctly, Oppenheimer asked physicists Bob Serber and John Manley to go to Santa Fe with their wives to spread the rumor that Los Alamos was making electric rockets.

Castillo Street Bridge

Castillo Street Bridge

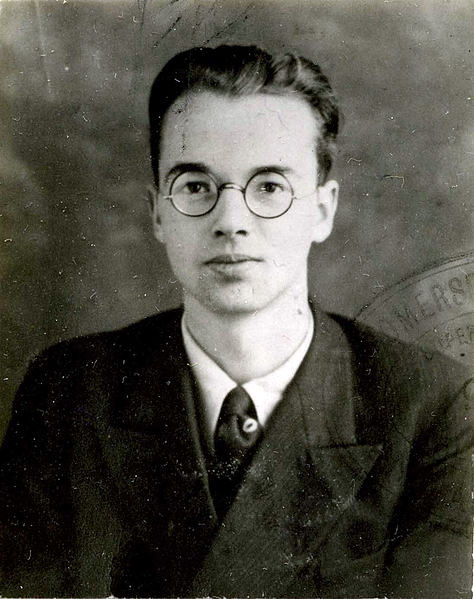

Another historic site in Santa Fe, the Castillo Street Bridge at Paseo De Peralta was where German physcist and Soviet spy Klaus Fuchs agreed to meet his Soviet Agent, Harry Gold, on June 2, 1945. Fuchs met with agent Gold many times over the summer of 1945 and gave the Soviet Union valuable data. Together with two other sources, Fuchs enabled the Soviets to expedite their atomic bomb development by at least two years.

Otowi Bridge

For more than twenty years, Edith Warner and her companion Atilano Montoya (nicknamed “Tilano”), an elder of the nearby San Ildefonso Pueblo, lived in a small adobe house next to the Otowi Suspension Bridge. “Otowi” in Tewa means “the gap where water sinks.” The house became a cultural crossroads between local ways of life and the Manhattan Project.

Dinner at the house at Otowi Bridge was booked weeks in advance. The house was decorated with beautiful Native American artifacts, pottery and paintings. Up to ten guests dined together at a single long, carved table. The natural light from the fireplace filled the room with a cozy glow. The food was simple and delicious: a stew with fresh herbs; posole, a Native American dish made with parched corn; poached fruit; and Warner’s magical chocolate cake.From 1928 to 1941, Warner was in charge of meeting the “Chili Line” railroad on its way to and from Santa Fe. With the outbreak of World War II, the train service ended. Warner agreed to Oppenheimer’s request to serve meals exclusively to Los Alamos scientists and their families in 1943.