[At the top is the edited version of the interview published by S. L. Sanger in Working on the Bomb: An Oral History of WWII Hanford, Portland State University, 1995. For the full transcript that matches the audio of the interview, please scroll down.]

Book version:

I thought the Hanford site was perfect the first time I saw it. We flew over the Rattlesnake Hills up to the river, so I saw the whole site on that flight. We were sure we had it. I called General Groves from Portland, and told him I thought we had found the only place in the country that could match the requirements for a desirable site. I said we had found a place with a spur line railroad, The Milwaukee Road, right into the place where we thought the facilities would be built. And that our property probably would include the switch station between Bonneville and Grand Coulee. Right on that 230-kv line. It had so much in favor of it. An area with almost no people, very undeveloped, it was obvious it had been built by the Columbia River in early times working across the valley leaving gravel behind it. And there‘s nothing better than gravel, deep gravel, for foundations, for earthquake protection, anything you want. It had all the advantages.

I told General Groves “I don’t see any point of going down to Southern California because there are too many strikes against it.” Groves said, “Well you better go ahead with your program. It will only take a few more days.” So we did. We came to San Francisco on Christmas Eve, we didn’t do anything Christmas day except go to a Chinese restaurant for Christmas dinner. We went to Sacramento, to the district engineer there. We pumped him about what there might be in Northern California. There didn’t seem to be much prospect of the combination of lack of people and development, and water and power. We went to Los Angeles, and we drove clear out to the Arizona border. We spotted some good possibilities. But the only water source would have been the Colorado River or one of the aqueducts. They were almost out of the question from the point of view of what hell would be raised if we tapped into either of those. We stayed overnight at Blythe, and spent most of the next day driving around the region.

We went back to Los Angeles, and I called Groves again and said I thought we had done all we needed to do. He said, “All right, come on back.” We wrote our report on the plane on the way back to Washington, D.C. We got there New Year’s Eve. We talked to Groves the next morning, the first day of 1943, and he quizzed us at length about everything but was very well pleased at what we had found. Before the end of the month we had authority to acquire the site.

I think there were two real critical things during the construction period. One thing that occupied the attention of a lot of high-ranking people was the question: Would it be possible to build an operating system that could handle the loading and unloading of the chemical separation cells and to do what-ever they might have to do, could you build a system that would let you put an operating unit that was bigger than this room down into a cell and connect it to pipes, maybe a hundred connections? These cells were built completely pre-fabbed as one piece, to a precision where they could drop it in place, and with equal precision have fittings around the outside to connect it up.

The other difficult thing that caused a lot of concern was the canning of the uranium fuel slugs for the reactors. It was such a critical thing if one of these slugs exploded. And we tested some that did explode, like a hot dog. Solid uranium popped out with jagged edges just like a busted weiner. That might have contaminated the whole process. We never knew for sure if a reactor would operate with some of these slugs exploded. We subjected the slugs to a degree of stress that would not be encountered inside the reactor, and we tested them with high-pressure steam which did not exist inside the reactor.

There were not a great number of scientists at Hanford. Maybe Du Pont had half a dozen top-ranking people, and we had quite a number of visitations from Met Lab people. Fermi, Wigner, Franck came, but Szilard didn’t visit. He was kind of sour because they hadn’t followed his recommendations in the beginning about a couple of things, like helium or sodium cooling.

Wigner was a smart nuclear physicist. I remember taking him around once when we were under construction. I took him through the concrete batching (mixing) plant we had set up and showed him how it all worked, the automatic features. Now it would be considered an antique freak. He ended up that tour by saying, “You know, I can’t understand how you can handle anything as complicated as a concrete mixing plant system.“ He was kind of a funny character. He was responsible to approve all of the Du Pont design plans relative to the operation requirements. I used to talk to him quite a lot because he was often a little delaying factor. We weren’t looking for any delays of any kind.

As far as my working relationship with Du Pont was concerned, of course, we had differences from day one. I was fortunate that Gil Church and Walt Simon (Du Pont‘s project construction manager and operations manager) were people I could deal with and respect, and we had a very good working relationship. I remember one time Granville Read (Du Pont‘s assistant chief engineer) called up Groves and said Matthias and Church were having a big argument about something and what should we do? Groves replied, “Well, if those two guys don’t have some arguments, then neither of them are worth a damn.”

Some amusing things happened. I had a letter one time that came to me, through probably 20 different places in the War Department, from a congressman who had a letter from a guy that worked at Hanford. He told this congressman that it wasn’t bad out there, they had good food and they were getting good pay and working hard but he said the big problem is that all the women in the area were behind fences and it was pretty hard to do it through a fence. I sent the letter back and all I said was, “Imagine that?”

I suppose there were brothels in Pasco, I‘m sure there were, and I‘m sure a lot of those shacks along the river between Richland and Pasco functioned that way. Those were problems to us, mainly because of health. We didn’t want any big, tough health problems to surface. It never happened. Du Pont had quite a group for industrial medicine. We kept them running around looking at all these places. We did some thoroughly illegal inspections, I’m sure.

It’s true the women lived behind barb wire, and we tried to control access. We know we didn’t succeed 100 percent. They would get the gals and go out in the sage brush, occasionally. And they were free enough, except they lived in these barracks.

We made up our minds when we first started that we would put people in barracks regardless of what they looked like. It wasn’t more than a few weeks after we started getting people in our camp that I had a visit from a whole bunch of black guys led by a black minister who said they would rather have their own barracks. They hadn’t had any real trouble, but they figured they would.

I dealt with the unions, and Du Pont and I did a good job of batting problems back and forth and confusing the labor leaders. I did that also with the colonel in Washington, D.C. who was head of labor relations. We kicked problems back and forth. I would say, that bastard in Washington doesn’t know what he’s doing. He would do the same thing, and blame me for all the problems. It worked great. We kept kicking them around until they disappeared.

We had a one-day work stoppage, by the pipefitters and plumbers. We didn’t have much trouble. Joe Keenan, secretary-treasurer of the Building Trades Council, came out from Washington to help us when there were potential problems. He was a great help to us. When I talked to Keenan, I had to guard against making dirty cracks about unions. You got the feeling he was one of you.

We didn‘t try to keep organizers away, we accepted the idea of union organization. We did not have a project contract. We agreed at the beginning with the labor leaders in the region that we would follow standard union practices. We set the basic labor rate at $1.05, the average between Seattle and Spokane. That was for common labor. Electricians and pipefitters got more. We had a fuss with them once, but we settled it, and I think gave them a little increase.

A lot of local people would ask us what was going on at Hanford. We rigged up a cover story right at the beginning. There was a new explosive developed just before the war that I think was called RDX. It was much stronger than gun powder, and dynamite, or nitroglycerin. When we started out, we spent some time thinking about what we ought to call it and what we ought to get together on when we were pressed. We ended up calling Hanford a place to make RDX. Nobody questioned it. Du Pont was known as an ex-plosives maker.

I handled the newspapers early. I got to Spokane, for instance, to talk with the Spokesman-Review and others up there the day the order came from federal court to start acquiring land. That must have been in January, 1943.

I went there, and I went to Seattle and Portland. Another man on my staff, Bob Nissen, covered all the little towns along the Columbia all the way up. I went to Yakima and Walla Walla. I told people I needed their help in keeping this project quiet. I told them it was a big important war project, and that’s all I could tell them. We had very few problems after that.

When I was given this job, I went to the war censorship department. One of the real high-ranking people in that organization was a guy who was a fraternity brother of mine at Wisconsin and we were very close friends. I went to see him and told him we needed all the help we could to keep Hanford from being publicized. He told me you know we can’t censor anything. I said I was asking for his help because he must have quite a lot of influence among the newspapers. He gave me a hot line telephone number and told me any time I had problems, I should call and they would try to intercede.

I told them, all the papers, any time there was news they could use, I would see that they had it. When this thing breaks open, I will see you get the word. I managed to keep that promise the day the first bomb was dropped.

We had one incident where Truman committee investigators turned up, and tried to get into Hanford to see what was going on. We had a deal with (Senator) Harry Truman that his special committee (to investigate national defense construction) would not bug us, an agreement between Truman and the secretary of war. I called Groves, and they were gone the next day.

One of the things I am most proud of is that I didn’t let a British scientific delegation get into the reactor areas and the other closed areas. They had a guy named Klaus Fuchs (the British scientist, later convicted of spying for the Soviet Union) with them. It was after the first reactor was operating, later ‘44 or early ’45. They didn’t have proper credentials.

There was never any indication of espionage or sabotage that we knew of, never any Russian or German activity. We had a few things happen. One guy wrote me a letter from Oklahoma and said he owned a radioactive spring, and would we be interested? We thought here was somebody who suspected something, but he turned out to be a mountaineer who wanted to sell water from a spring. I did have a military counter-intelligence group of 10 or 12 very carefully selected people, most of them with FBI experience.

There were some Indians at Priest Rapids, 30 to 50 of them, and they wanted to fish for salmon at White Bluffs, one of their traditional fishing places. White Bluffs was about 15 miles from their village, which was farther north. I had a number of visits with the Indians and was invited to one of their tribal festivals. They didn’t like the idea of having to get a pass. I had a formal meeting with Johnny Buck, their chief, and explained to him that if you don’t let us give you passes, and you are admitted through our gates, somebody in this big work force might do some damage and accuse the Indians since we gave you free run. I‘ll arrange to take your people up to the White Bluffs island every morning by truck and you can do your fishing and bring you back by night or in some cases maybe let you stay there overnight.

I called them Priest Rapids Indians, but I think Wanapum was their right name. The first time I met Johnny Buck he produced a little weatherbeaten treaty which gave them the fishing rights. I liked him. That guy ruled the tribe. He chased them into the river once a week in the summer.

Hanford was a lot different from my later career. It was very much different in that I had ways of getting things done that put tremendous pressures on people because of the war effort. I had a senior officer in the Army, Navy and Air Force I could appeal to if I ran into problems. That was great. We did everything in record time. We had the authority. We didn’t wait for anybody.

Full Transcript:

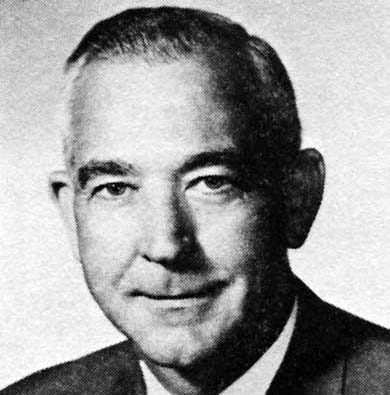

Stephen L. Sanger: What follows is an interview on April 23, 1986, with Franklin Matthias at his residency in Danville, California.

Sanger: I saw Jim Grady and he went with you on the trip to Hanford, right?

Matthias: Yes. Originally Jim was going to be—I thought he was going to be in the operations side of it, but that was the only trip he made and the only activity. Then he got moved and [Walter] Simon got moved, him in charge.

Sanger: You, [Gilbert] Church and [Jim] Grady went to Hanford, and were you sort of the official team that recommended it, or what?

Matthias: Oh no. No.

Sanger: He [Jim Grady] did not go with you to the other places, did he?

Matthias: No, he did not. That is the only trip we made together and the only time I saw him really and associated with him. No, our site selection team—I was in charge and Gil Church and Al Hall. A.E.S. Hall was then their principal civil engineer in the design department.

Sanger: For DuPont?

Matthias: For DuPont. He was a good deal older. Gil and I were about the same age and he was quite a lot older. He kept working on the project.

Sanger: Did he go with you to the various places?

Matthias: Yes.

Sanger: Church did, too?

Matthias: Yes. The three of us made all of this together, except one time we separated because we went to the Yakima Air Base and they would not take the civilians in a plane but they took me. I made a tour around northern Oregon in a photography plane with a transparent bottom.

Sanger: Oh really?

Matthias: Then, I made this trip while they drove from Yakima around through the project from the west. We met then in the Pasco Naval Air Station. All three of us were just completely convinced that we had seen the only place that we could ever find that fit all the requirements.

Sanger: That was you, Church and—?

Matthias: Al Hall. Al Hall helped us considerably, too, in the town planning later. He was in the Engineering Department.

Sanger: Where had you gone, then? I guess that is in the diary you have on file at Hanford, I guess. You went to California, too, right?

Matthias: Oh, yes. We had asked the Seattle district to send us an officer that knew that region well. We met him in Yakima. We had intended to go to Seattle, and the plane travel was all fouled up and we ended up in Yakima. This guy came over to see us to spend some time with us and he did, and he really knew his business. That was Captain George Hopkins.

Sanger: H-O-P-K-I-N-S?

Matthias: Right. He was a big help to us in that area because he knew that country cold. Every little town and every little place. We spent some time in a hotel room in Spokane for a few hours going over a bunch of air navigation layouts, and we had a fair idea of what the requirements for a site, and the size. We knew it was like 600 miles because of the clearances that the scientists had specified. We made a template of a layout of Hanford with all of the protected zones around it and with the reactors located and the separation plants located. All we knew then, there were three of each. We were supposed to get a place for six of each, six reactors and two separate separation areas.

We ended up building three reactors and one of the separation areas that had two buildings in it. Then we used that and put it on navigation maps to get an idea of what kind of towns and what sort of development, what sort of access there was and we had identified about four sites in the northwest.

Sanger: Which was what?

Matthias: Now, we went to the Northwest because of power. I should go back a little bit. We had our meeting on the 14th of December in Wilmington [DE], which was really the beginning of the Hanford project. We had a bunch of scientists there who spent all day trying to figure out what were the radiation hazards, and they did not know but they were speculating. Anyhow, that set up the rules for the site requirement.

Sanger: The distance?

Matthias: The distances and the kinds of things we had to have. We had to have water and we had to have a lot of power. We, of course, wanted a site that was favorable for geotechnical conditions and building, weather, everything that pertained to a good building site.

Sanger: Do you remember, incidentally, if at that time it was known if it would be water-cooled or helium?

Matthias: No, it was not. That argument went on for quite a long time.

Sanger: But they wanted, just in case they used water, they wanted it close?

Matthias: The site requirement specified a large amount of clean water.

Sanger: Just in case, I guess?

Matthias: It was more than just in case. There was a controversy among the various scientists about which would be the most effective and it finally ended up water, partly because we had such a good river near us, I think. I never did follow all the arguments. I know they were there. As long as we had the water available, I did not worry about it.

Sanger: I guess that water was easier and apparently cheaper too, if they could use it.

Matthias: Oh yes. Helium is not a good material to transfer heat. It would have been a more complicated reactor.

Sanger: Was the electricity needed mostly for the construction or for the operation?

Matthias: For the operation. They guessed that we would need, as I remember, something like 150 to 200,000 kilowatts.

Sanger: That is to run the pumps, I suppose?

Matthias: To run the pumps. Whether it was helium or water, it took a hell of a big basic power plant to handle it. With helium, I think it would have been much more because it would have had to circulate a much greater amount.

Sanger: Yes. I think there is a recent book out that mentioned that.

Matthias: Well, this was a big argument. I think it really was settled finally by General [Leslie] Groves who said, “Well, we cannot argue about this forever. Let’s go water. We know how to handle water.”

Sanger: I was talking to [Eugene] Wigner, who is still a bit irascible about certain things. He has come back now to criticize DuPont.

Matthias: He has?

Sanger: Yes, saying various things. I am not going to ask you about some of that. He said he would just as soon have built the plant on the Potomac River, as far as he was concerned. There was water there and he was not worried about the radiation danger. I had never heard that before, but I heard other places.

Matthias: He was just Wigner. He was a smart nuclear physicist. I remember taking him around Hanford once while we were under construction. I took him through the concrete mixing plant we had set up at one of the places and showed him how it all worked and all of the automatic features and things. Now, in our very modern practice, that would have been an antique freak. [Laughter] He ended up that tour by saying, “You know, I cannot understand how you can handle anything as complicated as a concrete mixing plant system like you have here.”

He is kind of a funny character. He was responsible to approve all of the DuPont design plans relative to the operation requirements. I know there were other people involved in it, but Wigner was the guy that was really the single responsibility for that. I used to talk to him quite a lot because he often was a little delay factor. We were looking for any delays of any kind.

Sanger: When I talked to him in Princeton—of course, he is quite elderly now—apparently he goes in stages, according to a friend of his. Now he is back on not liking DuPont, and he said that they just did not know anything about nuclear physics and so everything dragged on a lot longer than it should have as a result.

Matthias: He is crazy.

Sanger: He said he could have done it nine months quicker if he had his way.

Matthias: You know the whole business of recruiting DuPont. They resisted Groves for quite a while on that very basis. They said, “We are chemists. We are not nuclear physicists.” Groves settled that by getting them to go to the Met Lab in Chicago and talk to Compton, Teller and Wigner and all of these people. He said, “They will be behind you and do whatever it takes to help you get acquainted, but you know this engineering and construction business better than anybody in the country and we have got to have you.” There was jealousy in the beginning because the scientists wanted to do it themselves, all of it. They wanted to run the whole program.

Sanger: Yes, I have heard stories that Wigner was the ringleader in that, too.

Matthias: He was one of them that pressed.

Sanger: He told Hilberry once to “Give me a hammer and some nails and I will build it myself.”

Matthias: Well, he was full of crap. He did not even know the first thing about it. Hilberry was a great guy, too, and a very big help to me.

We then spent one day finding out where there was power and picking the brains of Corps of Engineers district guys who had been district engineers around the country. We told them what kind of a site we wanted and what we needed without getting into specifics too deep.

Sanger: Yes.

Matthias: Then we talked to the guy who was in charge of power for the Corps of Engineers and electric in the engineering branch of the Corps. We decided that the only places that were practical from a power point of view was possibly in the Tennessee Valley area but more likely in the Northwest. The Shasta Dam was coming in and the Coulee was here. That really directed us to the West coast area. There was not anything in the middle of the country. One of those scientists, and I think Arthur Compton had made this proposal, that it ought to be in the northern peninsula of Michigan.

Sanger: Yes. I heard that from John Marshall.

Matthias: I would expect he would know that.

Sanger: He mentioned he thought it was Lake Superior. He could not remember for sure, but it was up there somewhere.

Matthias: It was the peninsula at the Michigan site way up there. It would have been a lousy climate.

Sanger: But where would you have gotten the electricity here?

Matthias: You would not have any. We would have had to build it.

Sanger: And they had water.

Matthias: We would have plenty of water.

Sanger: It would not have been running water.

Matthias: And a remote area. A pretty remote area. The topography and the geotechnical conditions were not anywhere near, in that region—

Sanger: Rigorous winter, though?

Matthias: Oh, terrible winter up in there. So we passed that by right in the beginning. General Groves was all high on the Horse Heaven Hills area. He had been a district engineer out in this region once. That was south of where Hanford is now.

Anyway, we worked and started out from Washington with a commercial plane flight. We never did get to Seattle. We had to stop off in Spokane when we were in the Northwest. Then we drove all around Grand Coulee clear up into—what is the lake up in western Montana right near there? The big lake?

Sanger: Flathead?

Matthias: Flathead Lake.

Sanger: Not Okanogan?

Matthias: No, it is there. It is not too far. Anyhow, it was in western Montana.

Sanger: Oh.

Matthias: We swung around there and then went to Coulee and we took a look and we spotted about two places in the Coulee area. One of them was just north and west of Grand Coulee in a big plateau area where there was almost no people and no development. That would not have been a bad place, up in the Bridgeport area, up in that region. We would have had to pump water. We probably would have had to build the Grand Coulee pumping station to get the water up, the amount we were talking about. It was about a 3,000 foot lift.

So, this was a very bad mark against the place because that would have been expensive forever and a problem. Anyhow, we covered that. Not thoroughly, but as best we could. Using our map we checked out some of the things that maps did not tell us. Then, with Hopkins’ help we figured we covered that region. Then we ended up at Yakima one night and we spotted about two places in northern Oregon that looked possible. That is when we went to the Yakima Air Force and I got a plane and they had to drive.

Matthias: I made the loop around covering the two places that we had in Oregon.

Sanger: What were they?

Matthias: I do not remember.

Sanger: It could not be in the desert, I suppose?

Matthias: No. It was in eastern Washington, yes. Eastern Oregon, from the middle to the east.

Sanger: Was there a river in there?

Matthias: Yes. There was a river. There was water not too far. We were not too far south of the Columbia in that area. I do not remember the specifics of it. Anyway, we met back at Pasco, and I thought that the site was perfect the first time I saw it. We flew over the Rattlesnake Hills and over up to the river. I saw the whole site on that flight. They drove in from Yakima and then drove to White Bluff and then back to Pasco. We were sure we had it. We drove that night and we stayed in Pasco that night, I think. Then we went to Portland.

Sanger: This was in February, I suppose?

Matthias: No, no. This was in December.

Sanger: Oh, December, okay.

Matthias: This was in December ’42. Anyhow, I think we drove back to Portland that night and Hopkins went back to Seattle. In the meantime, I called the Los Angeles Corps District in San Francisco, giving them some of this requirement stuff and asking them to be ready to tell us about what they could figure out in both offices.

That night I called General Groves from Portland and told him I thought we found the only place in the country that could match for a desirable site and his first question was, “Is it Horse Heaven Hills?”

And I said, “No, it is on the north side of the river from there, but it is up in that part of the country.”

In Horse Heaven Hills the topography is lousy, difficult transportation. We are picking a place that has a spur line railroad from Milwaukee right into the place where we would feel that these facilities were going to be built, and that our property would probably include the switch station between Bonneville and Grand Coulee. Right on that big 230-Kv line that then was a big one, high voltage. They are not any more. They are going up to 500,000 volts in direct current.

It had so much in favor of it. An area with almost no people, fairly undeveloped. It was obvious that it had been built, that whole area by the Columbia River, in early times just working across the valley and leaving gravel behind it. There is nothing better than deep gravel for foundation for earthquake protection and anything you want. It just has all of the advantages.

We were very enthusiastic about it. Church and Al Hall were just as enthusiastic as I was. I said, “I think we have found it. I do not see any point in going down to southern California because there are too many strikes against it, or in southern Oregon.”

He said, “Well, you had better go ahead with your program. It will only take a few more days.” So, we did.

I remember we came to San Francisco Christmas Eve and we did not do anything Christmas Day except go to a Chinese restaurant for Christmas dinner. Then we went to Sacramento and talked to the district engineer there and just sort of pumped him about what there might be in this northern California area. There did not seem to be much prospects of the combination of topography, the lack of people and water and power.

We did not do much more then but to go right down to Los Angeles. We drove with a Corps of Engineers car and the guy from the district all through clear out to the Arizona border, that whole desert area. Through Barstow and that whole region. We spotted a couple of good possibilities that were good in some respects but the only water source would have been the Columbia River or one of the aqueducts.

Sanger: You mean the Colorado?

Matthias: The Colorado, yes.

We stayed overnight at Blythe at the air base. Yes, it was the air base. We spent most of the next day just driving around the region and then we went back to Los Angeles and I called Groves again and told him that we covered them and that I thought we had done all we needed to do. He said, “All right, come on back.” We wrote our report on the plane on the way back to Washington. We got there New Year’s Eve. We met with Groves the next morning.

Sanger: The first day of the year.

Matthias: The first day of the year. He quizzed us at length about everything but he was very well pleased with what we had found and where it was. He said, “I am going to have to go and see it before I go ahead and promote it hard.” We assumed it was all right and we went ahead and tried to refine something of our boundaries and some of the things that we could find out in the next few days.

Groves then did get out to see the place. I think it was about the 19th or 18th of December [misspoke: January]. That was the time that Gil Church and Grady and I got hung up on transportation. We did not meet Groves there. He got out there on time and went around with our real estate man that we borrowed from the Portland district and saw the place. He was leaving Pasco just about the time we were coming in, early in the morning the next day. Then, he took a train back to Washington and I took a plane and I got there a day earlier.

Anyhow, right that week we got the authority to acquire the site. In the middle of January or a little bit after. That was record time, too.

Sanger: Some of that was leased, wasn’t it? The government leased it? You did not buy all of it?

Matthias: Yes, we kept talking about 600 square miles. It was a little more than that. That included about a four mile strip all the way around except on the southeast where Richland was. We had under our control the guts of this thing plus a four mile strip; over about two-thirds of it. We were over on the north side of the Columbia River only with our leased area where nobody could build and live during that time.

Sanger: So then the government controlled the rest of it?

Matthias: Yes.

Sanger: It was leased across the river?

Matthias: It was leased across the river and was leased some distance to the west and to the east but not as far south as Richland. We included that in the tight control area.

Sanger: You talked about the rest of that. I have just a couple of questions before I forget—

Matthias: Let me tell you something interesting.

Sanger: Okay.

Matthias: One of the things I had always constant trouble with was not being able to explain to all kinds of authorities and divisions that we had to depend on just what the heck we were doing and what kind of demands we were going to be making on them.

I remember one particular case where Gil Church and I spent a couple of days way early in the game, as soon as I was appointed. We worked out a whole bunch of standard letter agreements that would give us the authority and the working arrangements with DuPont what they had to get approved and what they did not. This took a couple of days. Then, I think it was about the middle of February that Groves actually assigned the Hanford job to me. I could find that time but I do not remember it offhand. I do remember that he called me in. I had been doing a lot of work.

Sanger: Talking about the difficulty of not being able to tell people what was going on.

Matthias: We made up pretty much a guest list of all of the heavy construction equipment we needed, automobiles and pickups. We knew it was not accurate, but we had to get a start. I took that to a guy that was in charge of procurement of that kind of stuff for the Corps and at that time it was all centralized. That was in Washington.

[End of Tape 1]

Sanger: What do you suppose the total [number of workers] might have been then, at the highest at the height including the operations and workers, the wives, Army, etc.?

Matthias: I do not know, but I would say that there were probably more like 50,000 people involved with the families that were around. There was a big bunch of them that lived around the area in those shacks along the river and out in the ranches. They would drive in and they would pick up and get gasoline rations.

Sanger: That would have been included in the 50,000?

Matthias: That would have been included in the 50,000. Our camp, I think, was about 45,000.

Sanger: That would have counted like the cooks and all?

Matthias: Oh yes, sure. Everyone.

Sanger: People in the mess hall? And that was considered construction?

Matthias: Of course. All of the employees.

Sanger: There is a figure, I forget where. It is in one of these things and it says 80,000. That cannot be right, though, can it?

Matthias: No. Well, there were 130,000 people recruited to work at Hanford.

Sanger: But, of course, they came and went.

Matthias: They came and went, yes. You can find any numbers in between. Sometimes they are misused because somebody found out something at a point in time and it changed. I remember that number. We had about 130,000 people went through our employment.

Sanger: I think that Robley Johnson mentioned that because he took photographs of them. In this box it mentions there was a little friction there between you and DuPont in ’45, I think, over Richland Village and the way things were going there. It was not anything serious. It mentioned, “Oh, selling too cheap or selling things back to the people,” etc. Also, a dispute about security in some of the outlying areas.

Matthias: I do not know of any specifics that I recall. Of course I had differences with DuPont from day one. I was fortunate that Church and Simon both were people that I could deal with and I respected. We had a very good working arrangement. I did not hesitate to criticize something that I thought was not good, nor did they fail to criticize anything my people were doing.

The guy next to me in that picture is Granville Reid, the guy in charge of DuPont for construction. Not design and operation, but construction. He called up Groves one day and he said that Matthias and Church were having a big argument about something, and what should we do about it? Groves replied, “Well, if those two guys do not have some arguments then neither of them are worth a damn on this job.” I enjoyed complete support from General Groves.

Sanger: Reid up here, what was his relation say to [Frank] Mackie?

Matthias: Mackie was in the design department. He was construction.

Sanger: Okay. Because Mackie, his official title was something like—this is Frank Mackie.

Matthias: Mackie.

Sanger: Manager of War Construction, I think?

Matthias: I think that could be. Reid must have been his superior because we talked Reid into getting Mackie out at Hanford and stay there because they were having to run too many things through to DuPont for decision. Reid would give the decisions.

Sanger: Reid was Assistant Chief Engineer and Mackie was Manager of War Construction. Somebody was above him named Wood who was General Manager.

Matthias: Yes. That is right.

Sanger: These things do not make a lot of difference.

Matthias: DuPont had an entirely separate organization start right from their Chief Engineer. Design and Engineering was one outfit, and this is another empire that is all of construction management.

Sanger: Such a huge company.

Matthias: I just cannot give DuPont credit enough for the job they did for us out there. They gave us the very best people they had. They did not spare any efforts to help us do what we had to do. I thoroughly enjoyed the relationship that I was able to maintain, because that is not normal on a big job like that.

Sanger: Do you recall a great number of scientists there, were there? Physicist types?

Matthias: Not a great number. DuPont had some very highly skilled people.

Sanger: But they were a handful compared to the bulk of them in the Corps?

Matthias: Yes. DuPont had maybe half dozen top-ranked people. We had quite a lot of visitations from the Met Lab people. We had [Enrico] Fermi out there and [John] Wheeler was there off and on for quite a long time, and we valued him very much. And Fermi and Wigner and [John] Franck. We did not have [Leo] Szilard out there much that I remember. He was kind of sour because they did not follow his recommendations in the beginning.

Sanger: I asked somebody if he ever visited and they couldn’t recall. Wheeler, I think, said he did not know.

Matthias: I do not think he was ever at Hanford while I was there.

Sanger: Did you have much difficulty with local people wondering what was going on out there?

Matthias: Not too much.

Sanger: I mean, they wondered, I suppose.

Matthias: They wondered.

Sanger: I think you told me there was an assumption there were explosives?

Matthias: We rigged up a cover story right at the very beginning and when we got pressed we would tell them. There was a new explosive developed just before World War II that I think was called RDX, which was much stronger than gunpowder and dynamite and nitroglycerine mixes. When we started out, we spent some time thinking about what we ought to call it, what we ought to get together on when we were pressed. We ended up calling it: it was a place to make TNX. Nobody ever thought further then. DuPont was making an explosive.

Sanger: They were known as an explosives company.

Matthias: There was some speculation among the workmen about it when we started building six feet thick concrete walls and things like that, that this must be some hot stuff. We did not get much. People were curious, but when they did not get answers they forgot about it.

Sanger: Of course, this sort of thing went on around the country, secret work like this. Maybe not quite as big as that. Also, you went around to talk to the newspaper editors. Was that early on?

Matthias: That was very early. I got to Spokane, for instance, to talk to the Spokesman-Review and others up there. The day the order came to the Federal Court to start acquiring—and that must have been in January still—I went there and I went to Seattle and I went to Portland. Then, I had Bob Nissen, who was working at Hanford in my staff as a public relations guy. I had him cover all of the little towns along Columbia all the way up. I went to Yakima. I went to Walla Walla. I talked to all of those people just to enlist their help in keeping it quiet.

Sanger: What would you tell them?

Matthias: I told them it was a big important war project and that was all I could tell them. Period. I remember going to Walla Walla. There were two guys that were brothers, the Richardson’s, who ran that paper. I sat there trying to break into them. They stared at me in a cold way and I was in uniform. Finally, I kept trying to find something to say that would register with them. Finally, I said, “Now just to give you an idea about what this is: this project is so important that it is not tied in with any of the normal Corps of Engineers activities.”

I said, “I do not report to the district or the division. I report directly back to Washington.”

They immediately said, “You mean you are not with the Portland District?”

And I said, “No. I have nothing to do with them. They are going to be told to help when we need help, but that is all.” And, suddenly we were friends. They had a hell of a grudge against the Portland District at that time.

Sanger: You went to Seattle too?

Matthias: Yes.

Sanger: And you told them the same thing?

Matthias: Yes.

Sanger: And you suggested what? That they not write about it, or what?

Matthias: I had a little more help than that. When I was given this job, I went to the Department of Censorship, war censorship. It happened that one of the real high-ranking people in that organization was a guy that was a fraternity brother of mine in Wisconsin. We were very close friends. He edited the daily newspaper one year at the university when I was editing the engineering magazine and we really got to be close friends. I knew he was there, so I went to see him and told him that we were going to start this big activity and that we needed all the help we could to keep it from being publicized for security reasons. He said, “Well, of course you know we cannot censor anything.”

I said, “I know that. I am just asking for your help because I know you must have quite a lot of influence among the newspapers.”

This guy had been drafted from Minneapolis where he was editor of one of the papers. He gave me a hotline telephone number and he said that any time I had problems that I could call and they would try and do something to intercede. He even gave me a note to say that I had discussed this with Censorship and they were behind me in trying to keep this under wraps as much as possible. I told them all that anytime there was some news that they could use I would see that they had it. I said, “When this thing breaks open I guarantee that you will get word as soon as anybody.” And I managed to meet that promise the day that the first bomb was dropped.

Sanger: Was there any coverage up to then?

Matthias: I had a few little problems with The Seattle Times. Just about everybody did.

Sanger: In what way?

Matthias: Oh, just that they started writing speculative stories.

Sanger: About what was happening there?

Matthias: Yes, about what was happening behind it. I just tried to keep them from printing anything that was not of real important news value.

Sanger: And you would talk to them?

Matthias: I talked to the editors or somebody.

Sanger: Would they ever bug you with reporters coming around?

Matthias: We had one incident where a Truman Committee investigator turned up and he tried to get into Hanford and he tried to get in to see what was going on. Well, we had a deal with Truman that his committee was not going to bug us, and that was made between Truman and the Secretary of War.

Sanger: So you got in touch with him or what?

Matthias: I called Groves right away and told him as soon as we found out about these guys. We found out, I guess, the first day that he turned up. They were gone the next day.

Sanger: Could they get in or not?

Matthias: No. We did not let them in. They were hanging around there just trying to talk. They had a motel down in Walla Walla, I think.

Sanger: But it was very difficult to get on the reservation?

Matthias: Oh yes. One of the things I am most proud of is that I did not let the British Delegation get into the reactor areas or the closed areas. They came and they had a guy named Klaus Fuchs.

Sanger: Oh. He was along with them?

Matthias: He was with them.

Sanger: When was that? Do you remember?

Matthias: No, I do not.

Sanger: And when the reactor was going?

Matthias: Oh yes. It was after we had one of them operating, at least one of them.

Sanger: So it would have been late ’44 at least?

Matthias: It would have been late ’44 or maybe early ’45. I think late ’44.

Sanger: On what basis would you not let them in?

Matthias: They did not have proper credentials. I found some things that were wrong. I took them around the area away from the important places.

Sanger: But he was along? Do you remember him at all?

Matthias: No, not until Johnny Wheeler started telling me about him, and that was many years later.

Sanger: Did you ever have any indication that you had any leaks or any espionage or sabotage type work there?

Matthias: No. We did not. We did not find anything. We heard some reports and there was some talk that people were not behaving themselves, but we did not find any evidence that there was any Russian or German activity up in the area. We had a few things happen. Some guy wrote me a letter from one of the works down in Oklahoma or some place that he owned a radioactive spring and would we be interested. We thought maybe he was somebody that suspected something, but it turned out to be a mountaineer that had a thing that he was selling water from his spring. We did not ever have anything that looked at all significant.

One of the things though, that we did—I had a counterintelligence group with me. They were about ten or twelve very carefully selected people. Most of them were with FBI experience in something.

Sanger: They were military?

Matthias: They were military but they worked in plainclothes. They were used to working with the FBI. I had a call from the FBI Director out in that region one day and he said, “You know, I am frustrated. I have been told that we are not to concentrate anything on trying to find out what is happening in the Russian Purchasing Offices and other places.” In Seattle and Portland, there was big activity because lend-lease was going on.

He said, “I am sure that the Purchasing Offices are, among other things, a cover for extensive espionage.” He said, “Nobody has told you that you cannot try to find out what is going on these offices, so maybe you can help me a little?”

And so we did. We did some regular work infiltrating into the offices and getting people to keep us posted on what was going on. We did not use it for anything but to give it to the FBI.

Sanger: And that was in Seattle and Portland?

Matthias: Seattle and Portland.

Sanger: The Russians had a purchasing connection?

Matthias: That was a big shipping port, you know, for lend-lease.

Sanger: The FBI man in Portland suggested that?

Matthias: I suppose it was. He tried to reach—I do not know how they were organized.

Sanger: But you did not find any evidence of funny behavior?

Matthias: Oh, we found a lot of suspicious stuff that we turned over to him.

Sanger: But not necessarily to do with Hanford, though?

Matthias: No, no. Nothing to do with Hanford, but we thought this would be a good way to keep on top of anything that might be coming in through the Russians. Roosevelt gave instructions to stay the hell away from the Russians. They were our allies. The Russians did not appear to appreciate that.

Sanger: Is it safe to assume that most of the men working out there were maybe a little older than the normal, because they were past draft age, were they?

Matthias: Yes, there were a lot past draft age but there were a lot of fairly young people too.

Sanger: They were 4F presumably?

Matthias: Yes. They always had something that kept them from being drafted. We had quite a lot. Some of them were darned good people. I participated in labor relations far more than most Army administered operations. I dealt with the unions with DuPont, and they did a good job of batting problems back and forth and confusing the labor leaders.

I did that also with the guy at the Corps of Engineers in Washington who was head of labor problems. We used to kick problems back and forth and I would say, “Well that bastard in Washington does not know what he is doing. But go back and try. I will go back.” And then he would do the same thing; blame me for all of the problems. It worked great. We kept kicking them around until they disappeared.

Sanger: There was hardly any stoppage at all. I think they said once there was a short one?

Matthias: We had a one-day stoppage of work.

Sanger: Of the whole place or just one segment of it?

Matthias: Just the pipefitters and plumbers.

Sanger: And that was the worst? I guess Mackie said when I asked him, “Why did you not have more labor trouble?” and he said because they never had a contract written down. He also claimed that he knew big labor leaders—national—in Washington on a first-name basis so that if you or he or whoever sensed something coming, there was an effort was made to get in touch with them.

Matthias: We did have some help. We did not have much. Joe Keenan was the guy that we got from Washington that came out to help us when there were some potential problems. He was a real big shot. He was Secretary Treasurer of the Building Trades Council. He came out of the electric unions and later he was President of the International Electricians Union.

Sanger: Was there an understanding or was it a constant battle to keep the organizers away?

Matthias: We did not try to keep organizers away. We accepted the union organization.

Sanger: These men were members of unions generally, right?

Matthias: Yes.

Sanger: But there was not any contract?

Matthias: Well, we did not have any. We just agreed at the beginning with a group of labor leaders in that region that we would follow the standard union practices.

Sanger: On the overtime, do you remember was it paid straight time or added?

Matthias: No, I think it was added but it was before the time when if you were on shift work you got an extra hour of pay that you did not work. Some of those rules have developed since then.

Sanger: Were they making good money when you consider the overtime?

Matthias: There was not a lot of overtime. For a while we worked Saturdays and that was overtime, of course. We had it all organized so we did not normally use much overtime. We had three shifts working on a lot of the stuff so there was not any time for overtime.

Sanger: I notice in this worker relations thing it mentioned that some of the supervisors were expected to work fifty-hour weeks and so on.

Matthias: Oh sure. And the DuPont people—those people did not get a premium for overtime at that time.

Sanger: Some of them were saying they worked six or seven days a week.

Matthias: Yes, they were beyond union levels. We started out, as I say, we set up the basic labor rate as $1.05, which was the average between Seattle and Spokane.

Sanger: That was for laborers?

Matthias: Just common labor. The laborers’ union. I think our electricians and pipe fitters were up to about $1.65. We had some fuss with them at one time about wages but we settled it all and we gave them a little increase.

Sanger: That is detailed in this book.

Matthias: I imagine it would be.

Sanger: There is a good long section in the back about wage scales and some of the difficulties.

Matthias: I always felt good about how we dealt with our labor problems at Hanford.

Sanger: It also mentioned in there some of the high absenteeism, at least at times, high turnover too.

Matthias: High turnover. After a dust storm, the next day we would lose 500 people or so out of our labor force. “Termination Powder,” I think we used to call it.

Sanger: It also mentioned that during the war time there were more jobs, the pay was better and so people had a tendency not work as long before they moved on.

Matthias: That is true.

Sanger: There were, of course, many jobs especially if you were skilled.

Matthias: About the time we were shutting down there was a big—I forget just where now, down in the Southwest or somewhere in there. A lot of our people went there and heard about it and wanted to get in on the ground floor.

Sanger: Yes.

Matthias: But it was not significant damage to us. I think one of the most remarkable things that happened was with our pipe fitters and plumbers. We had a guy from Forrestal, the Undersecretary of War’s office, who was sent out—Groves arranged this—to see all three of the main projects at Los Alamos, Oak Ridge and Hanford. That was after we had gotten going a ways. He arranged for this guy to go, and Forrestal wanted some assurance that these jobs were being well managed and everything else.

He came out to our project and I spent about two or three days with him and covered the whole works. He said, “Now, if we have some problems that we can help at be sure and give me a call.” His name was Madigan. He was a very well-known civil engineer from New York. He was a dollar a year man; very highly competent. He made a tremendous success of his own business in construction engineering.

I think he was out there about the time we were having trouble getting pipe fitters. We spent some time discussing what we can do about it. That is one time he mentioned, “Go down to Texas, there are probably some loose ones down there.” He said, “If that does not work maybe we can think of something else.”

So we did. We went right after to that area and we did not have much luck. We could not even get a decent plane-load to come back. I called Jack Madigan and told him about it and we sat on the phone talking.

He said, “You know, I have been wondering for quite a while if there is any way we could use people in the Army who are on limited service. Could we use them more effectively in the business activities than we can in the Army?” He said, “Maybe there is something to that.”

We talked about it some more and finally I told him, “We figure right now that we need about 600 more pipe fitters for about three months to get back on track and get this work done.” Maybe that was not the right number; it was probably two months.

Anyway, he said, “Well, look. Why don’t we try this? We could release qualified people from the Army, take them off active duty, if they were skilled, we would have to get the union to agree to accept them, but we could send them out there and put them to work. If we discharged them from the Army they would become employees of the contractors and this might be a way to get out of the deadlock we were in.”

And furthermore, if there were guys released from the Army to work out there this could have a hell of a morale effect on all the rest, especially the pipe fitters who probably figured they had a hammerlock on us. Anyhow, we set that up in just a few minutes on the phone and the next week they started coming in.

I told him, “Let’s try it with about 200 or 300. I will get the unions approval of it.” And I did, even though the pipe fitters were a tough bunch to deal with. They did not have much to argue about because they could not supply people.

So they gave them all working permits whether they were union men or not. Their Army records showed whether they were competent pipe fitters or plumbers, and they started coming in from about seventy-five or eighty different Army bases in the country. They were ordered to Walla Walla Hospital for separation from the service.

I remember I took my labor relations officer and I went down to meet the first batch that came in. We got them in before they got processed at all. We got them into this big room and we had, I suppose, forty of them this first time. I explained that we were trying to get some help getting a major project finished that was very important to the war effort and the reason for them to be there is to help us out and that they could get civilian wages, whatever is paid to either the employee or the contractor, but we would expect you to have some influence on your fellow workers to try and get some better productivity out and so on. You have a chance right now to go back to your station or accept this.

I said, “One thing you are going to have to live with a fair restraint on your behavior because I can simply call up Salt Lake City and give them your name and you are back in your station the next day.” There were only a couple that turned it down and in checking into it further they were guys that had such a big family they were making more money in the Army then they would have been there with the extra allowances.

Anyway, we got about 230 or 240 of them on the job. Then I spent some time with the DuPont Company deciding just how we were going to use them. Are we going to make a squad of them to put in an area or mix them up with the other men? We decided to try both. We got about four or five that worked together. All of them were guys that had been on Army reserve. Then, we mixed up some crews. We could not find out much difference but all of a sudden, in one month, we were caught up with our pipe-fitting. It worked so damned good. Oak Ridge was having the same problem and when we got caught up and did not need them anymore the whole batch went to Oak Ridge and they did the same kind of job there for about a month. It was amazing.

Sanger: That was a stroke of genius.

Matthias: It really was. That guy Madigan, he just cleared the way for all of that to happen for me.

Sanger: I noticed this book in here by a guy named Jones who was writing a book apparently for the Army. What was that? There is a little bit in there about the Priest Rapids Indians and this guy Johnny Buck. Apparently there was a note in this box, about how he sent you a note once asking about why he and his people could not go through Hanford to get to the river.

Matthias: Yes.

Sanger: I guess that was just a question of getting through Hanford because they wanted to fish at the Yakima?

Matthias: They wanted to fish at White Bluffs. That is where they had traditionally gone. There are some islands in the river right there, and that was convenient for their fishing. That was about fifteen miles from their Indian village.

Sanger: Which was farther north?

Matthias: Well, yes, just after the river comes from the north and makes the swoon to the east. It is right about that corner. They were just outside of our project area. It is true; the only access they had was to come from Yakima Road around the end that got them into our project and then they had to go out to get to their village.

I had a number of visits with the Indians. I was invited to one of their tribal festivals.

Sanger: I think I noticed that. There is a photograph in there. Yes.

Matthias: Anyhow, I talked to them. They did not like the idea of having to get a pass. I had a formal meeting with Buck, the Chief, and I explained to him, “You know, if you do not let us give you passes and you are admitted formally through our gates, somebody in this big work force or anybody could do some damage somewhere around, and they would accuse the Indians of doing it if we gave you free run of the place.”

I said, “Now, relative to your fishing, all the time during construction and after that we will have to work out something different. But I will arrange to take your people and do the fishing out to the White Bluffs Island every morning in a truck. You do your fishing and take it back that night, or we can even in some cases let you stay there overnight. But, we will take care of your fishing problem.” They did depend on the fish for their food. That settled that problem.

Sanger: So you did that?

Matthias: They did all that. I sent a couple of WACs [Women’s Auxiliary Corps] out there to register all of the Indians in the tribe and give them passes. They enjoyed that, too.

Sanger: How many were there about? Do you remember?

Matthias: About thirty in the tribe.

Sanger: That was it?

Matthias: They said in the winter they might have twenty more people that just come in and stay during the winter, but the normal tribe was about thirty.

Sanger: They were fishing for salmon, I suppose?

Matthias: Yes, fishing salmon.

Sanger: And that was during which time of year?

Matthias: That would be late summer.

Sanger: That was Johnny Buck?

Matthias: Yes. Does your publication have a picture of the current Chief? It was in one of your articles a couple of years ago.

Sanger: It may have, yes.

Matthias: It called him Johnny Buck so I think it must be a descendant, because this guy was pretty old. I mean, he was fighting a losing battle of keeping that tribe intact.

Sanger: What did people of your position do at Hanford for recreation? Mostly parties, or what? You did not have a whole lot of time I suppose.

Matthias: We did not have a lot of time. We had parties, yes. We had a club for my staff and officers. When we acquired the site, we acquired all of the land of the irrigation district that supplied water up along the river except one piece of property, and that was west of Richland towards where the Yakima makes its loop, right up in there. It was out in those Flats and it was a ranch, and he was fairly successful. For us to acquire that district—which we needed everything else including the power generating plant and the pump station—there is a principal in law relative to these that the last faithful owner of a district still owns the district. We could buy the land, but we couldn’t buy the district without buying that piece of property. We had to go through a lot of silly legal gyrations to get it but we got it, and we bought it from the guy in a deal that was mutually satisfactory. We made that a little club, an employee’s club for the engineering crew.

Sanger: That was sort of west of Richland?

Matthias: That was west of Richland.

Sanger: Is it still there, I wonder?

Matthias: I think so. It was there the last time I was up there—not the last time I was up there; it was there when I was up there in ’68.

Sanger: That was for Corps of Engineers employees?

Matthias: Mainly for them but they could invite other people. The DuPont people participated too.

Sanger: Kind of like a country club?

Matthias: Just a little club a little bit away.

Sanger: Without the golf course.

Matthias: Yes. We never made it a good-looking place. It was just a ranch house that we occupied but it was a very good morale builder.

Sanger: Did you have children there?

Matthias: No, I did not have any.

Sanger: You would have been there as long as anybody wouldn’t you? Did you move into resident Richland right away or what?

Matthias: I moved to Richland in March of ’43.

Sanger: You stayed until early ’46?

Matthias: Until March of ’46 is when I got out of the Army and left. I was in Richland that long; three years.

Sanger: How does the Hanford experience compare to your later ones with dams and the aluminum operation?

Matthias: Well, there was an awful lot of the same kind of problems. They were major projects and any time you have a major project you set up a new routine for the local activity and social affairs and politics and business and everything else. Richland and Hanford was not any different from that. It was very much different in the fact that I had ways of getting things done that would put tremendous pressures on people that did not want to do them.

Sanger: Because of the war effort?

Matthias: Because of the war effort and because I had a senior officer in the Army, Navy and Air Force that I could appeal to if I ran into problems. They knew who I was and if I called them they knew they had to get busy and try to do something about it, and that was great to have that. But it also gave you a lot of responsibility in that you could not go to them with any simple kind of problem. You had to take care of your own business. I did not have to use it many times.

Sanger: Did you ever have any dealings with anybody in particular as civilians in the area more than other people for any reason?

Matthias: Not an awful lot. I know we did a lot of discussion and planning with the school district in Richland and the principal of that district I got to know fairly well. I do not remember his name now either.

[End of Tape 2]

Sanger: What do you remember about the Japanese fire balloon?

Matthias: That is very interesting. I cannot find any record of where I noted of when that happened. And I think it must have been around Christmas in ’44. And I was not on the site when this fire balloon hit our transmission line.

Sanger: You were not?

Matthias: I was not, I was on a trip someplace. And as soon as I got back I remember my Officer of the Day came around and told me about what had happened. But what did happen was that one of these fire balloons draped itself over the transmission line just over the hill. I cannot remember now the town and place, but it was a town on the road to Portland from Richland.

Sanger: Portland?

Matthias: Pasco.

Sanger: But was it on the reservation?

Matthias: No, it was on the transmission line between Coulee—it was not that far, it was just a little bit off past Richland. The line did not go through Richland, but just a little past, almost within our property.

Sanger: But it would have been south?

Matthias: It would have been south and west of Richland.

Sanger: I always assumed it was on the Hanford.

Matthias: Well I think maybe it was on the Hanford property, but just barely. And I do not know, I just happened to see the place.

Sanger: It just happened once?

Matthias: Just once.

Sanger: But it didn’t knock anything out?

Matthias: Well it draped over the transmission line between Bonneville and Coulee.

Sanger: Is that the main line?

Matthias: That is the main line, the main point of contact. We had a lot of stuff built into both of those major substations. And if there had been a real power outage in that part of Washington, Hanford would have still gotten power from one or the other. Any breaks in between would not have made a difference because we would still be hooked into one, and it was a quick closing breaker set up that we had installed. And we lost, I think it was twelve cycles out of sixty, that is, one-fifth of a second, that this short circuit across the line, by the shrouds of the balloon, short-circuited the thing and knocked out the power. And it went right back as fast as our equipment would make it. But it did shut down our reactor.

Sanger: Do you remember which one?

Matthias: I think it was B, I think it was the first one.

Sanger: Because it momentarily even slight shut it down.

Matthias: Well that was enough, we had it rigged you know. If the power went off, the emergency rods that were suspended above the pile through a series of wells would drop down in and with the cobalt just knock out the radioactivity and the flux. And it shut down the reactor. And when I read about it the next day, I was delighted. They found out the reason was they knew what had happened and started the thing up again. It took about three days to get up to full speed again. But we never had guts enough to test that under a full load. We did not know for sure that that device we had as an emergency shutdown would work. So this proved it for us. It did work. And I used to say, this is the first damage done by direct enemy action in this country.

Sanger: Yes, that is the distinction; it was the only time when enemy action shut down a war plant in the US.

Matthias: Now there is something else about—those balloons were all secret right away, both Army and Navy put the lid on as soon as they found out about it. But there is an interesting story that I think is true that I got from I think the Navy security about the time I was leaving the project. The Japanese started this fire balloon thing with a great fanfare and they were really going to put the US out of business by burning it up. And so the interesting thing to me was—and I knew about these two incidents that had been reported—one it seems to me was in Montana and another one Dakota or some place.

Sanger: There was one is Oregon.

Matthias: Well one in Oregon and one in Montana then. Yes, where they picked up the thing and it blew up afterwards.

Sanger: Yes, it blew up.

Matthias: But the first one was found, I think farther east than that though. And it was reported in a local county newspaper, a weekly newspaper. And then shortly after that, maybe within the same week that this was reported, was the one that was found in Oregon where it burnt. And they figured out what it was.

The interesting thing to me was that this security guy said, they got a report out of Japan two weeks after the first one had been published in this paper, quoting this newspaper about the damage was done by that fire balloon and it had not even exploded. It was there and some kids found it on a picnic. I just could not believe that this was right. Of course, I do not have any evidence that it was. They had no reason to tell me that if they did not want to.

Sanger: This one though at Hanford never burned, it just shorted it out?

Matthias: It never burned.

Sanger: Do you remember, were they made of paper, the balloon part?

Matthias: I do not know what they were made of, no, I do not know.

Sanger: This guy Grady, I guess went back to Hanford later, and he was in—

Matthias: Oh yes, well he could have. I do not think he had any formal—

Sanger: Yeah, he said he ran the peripheral thing, maintenance and so on.

Matthias: Oh yes, that could be.

Sanger: Anyway I got a letter from Simon the other day, who is interested in this project, and he said that he remembered counting forty or sixty that he had seen go over Hanford, that part of the country, high, really high up. And he assumed that is what they were I guess, because they launched 8,000. He seemed to know something about it. And he described the one that came down.

Matthias: There has been some publication about it.

Sanger: Yes there was. He has a little booklet he showed me once about it. But that was a fluke in a way because it was the only plant that was—in fact John McPhee mentions it in a book about atomic energy that he got from Wheeler I think, or some of the details about it.

Matthias: Wheeler would have been around there then because he spent quite a lot of time after we got that first reactor going, because on September 19, 1944, we started the first reactor.

Sanger: Did you ever know Leona Marshall?

Matthias: Yes, oh yes.

Sanger: She is at UCLA.

Matthias: I can tell you where I met her. One of the things that I had to do on the side was some work when the Met Lab set up the Arlington Station, just south of Chicago. I met Leona Marshall there, but that was not her name then.

Sanger: It was Woods.

Matthias: Woods, yeah.

Sanger: Originally, then it was Marshall, now it is Libby, because she divorced and married Libby.

Matthias: Yes, but she was a great gal.

Sanger: I guess she was about the only woman—

Matthias: About the only woman of consequence.

Sanger: Physically she was out there, right?

Matthias: Yes that is right. She was there for quite a little while.

Sanger: I think she said her and her husband were out there for about a year and a half, because they had a kid and for some reason they would not let them leave.

Matthias: I think they came about the time I left or a little before, I do not remember for sure. It seems to me, though, I did meet her when she came out there.

Sanger: Yes, her husband was one of the babysitters on the reactor and one of the physicists who was around in case of trouble. Well I guess she did the same thing, but she worked with Fermi whenever he would show up.

Matthias: Oh yes, because they worked her very close together in the Met Lab before.

Sanger: And she was the only woman who was present at the first reaction to the chain reaction in Chicago.

Matthias: Yes. I do not understand why DuPont does not have, or the office in Richland does not have some record of that balloon.

Sanger: Oh, they do not?

Matthias: Apparently they do not, I have had several letters from people who want to know about it, and my notes do not carry it, but I remember it so very distinctly.

Sanger: Well that is funny, well Simon, coincidentally in this letter I got from him, mentioned it.

Matthias: I know they know it happened, but I have never been able to get a date.

Sanger: You do not have that book by John McPhee probably, “The Curve of Binding Energy”?

Matthias: No, I do not.

Sanger: It is in there and I do not know if there is a date or not. Wheeler talked to him about it, they used to be neighbors I guess in Princeton, and he may have a date, there must be a date in there, maybe not though.

Matthias: Well, I do not know.

Sanger: Well, it would have been after September, we know that since the reactor was operating.

Matthias: Well, it was after that and the reason I remember it, I think it was the time when we had the Kay Kyser band up at Hanford, at the camp. And this, I think, was just before Christmas.

Sanger: Hmm, maybe that was ’44.

Matthias: That was ’44.

Sanger: Yes, because the camp was deserted by what February or March.

Matthias: Oh that is right, but it was going strong at Christmas time. We cut our forces 25,000 people in about three weeks.

Sanger: When construction was more or less over.

Matthias: When we started the third reactor, which was closest to the Hanford camp. And we moved a whole bunch of people down in the 300 area where we had some barracks and some other things.

Sanger: I once read a booklet, maybe a ninety-page booklet on fire balloons, and I think it is a government publication. Surely that would mention that in there.

Matthias: I would think so, but that was secretive as hell.

Sanger: A friend of mine is interested in that for some reason, he lives in Hawaii. I will have him send me that, I think that is his book, and if it is in there, I will make a copy of it.

Matthias: That would be great; I would like to have that. But sure, I know most of these people, probably four or five I do not.

Sanger: This guy here, [Cyril] Smith, was a metallurgist at Los Alamos. He was the chief metallurgist, he was in charge of the plutonium that came from Hanford. And I just talked to him because I wanted to hear a description of what they did to it. And he was the guy who put it in the Trinity bomb. “So the bomb fit in your hand,” he said, “Very nicely, that was the biggest thing.”

Matthias: I did a lot of speeches after the bomb dropped and Hanford was not too much interesting to me after we got it into operation. Operation is always a dull kind of an activity compared to the fuss and pressures of construction it was nothing. So I spent about all the time until I left running around the Northwest giving talks about the project.

Then I went to Brazil and I gave a talk on it in San Paolo to the Formal Engineers Association, and in Rio [de Janiero], because I worked in both cities. We came to San Francisco once and I may have talked to the Electric Club here, and there were about 500 people at that point. And we were sitting up in the hotel room the afternoon before and I had Milt Sidell, who is my Public Relations Officer, and somebody else—probably Joe Sally, he was my man on Operations. Anyhow, we were sitting there and I said, “You know, they keep asking me questions, how big was the bomb? How much plutonium was in the bomb?” And I could not tell them, I did not want to.

Sanger: You knew though?

Matthias: I knew. So we sat there that afternoon and figured out how many atoms of plutonium were in it. And it is like something times 10 to the 25th power, you know.

Sanger: Yeah, yeah.

Matthias: And so I used that after that frequently and everybody laughed, and that was the end of it. But in San Paolo, I made that statement and a guy in our company, a Brazilian engineer, came up to me the next day and he said, “I make that about twenty-five pounds, how close am I?”

And I said, “You are closer than you ought to be!” [Chuckle]

That was it. It was about twenty pounds. And they say that the real explosion was about three or three and a half pounds.

Sanger: Yeah, Smith said that it was about as big as an orange. He said it was warm.

Matthias: Yeah, it’s a very heavy metal.

Sanger: One figure that has been given is about fourteen pounds in one of the books, but there was not any source for that. But it’s in that ballpark.

Matthias: It’s a small amount, really.

Sanger: He was a real interesting guy. He had never been to Hanford before and he just dealt with it after it was made into plutonium oxide. It was a pink powder by the time he got it, it had been changed from the syrupy nitrate.

Matthias: We shipped it as a nitrate solution.

Sanger: I’ve spoken to [Walter] Simpson, that lieutenant who ran the convoys. He lives over there, he is retired and he lives along the levy there in Richland. Apparently he does nothing but eat and drink beer and he has hobnobs with his buddies, but he was quite a talker. And one of his old drivers, a sergeant, is his friend now and they are retired together.

Matthias: That was a good operation but it took us quite a while to come to it.

Sanger: Yeah, I imagine. After you were done with the plutonium, it was stored in some bunkers wasn’t it? In the mountain?

Matthias: Yes, in Hanford.

Sanger: There are photographs of them in DuPont’s unpublished history. I suppose they are still there?

Matthias: All I saw was the gate. I suppose they are still there. I don’t know.

Sanger: It had a description; it didn’t say what, but I think it said it was for product storage or something.

Matthias: Yeah. We stored it in the same boxes that we shipped it in so that you couldn’t get any of it to a critical mass.

Sanger: Then it went into some sort of container in the converted ambulances.

Matthias: Right.

Sanger: And it was kind of a syrupy solution?