Stephane Groueff: Hello, Dr. Wigner?

Eugene Wigner: Yes.

Groueff: Good morning sir. I am calling from New York. I am the correspondent of “Paris Match” magazine. My name is Groueff.

Wigner: Groueff?

Groueff: Groueff, G-R-O-U-E-F-F.

Wigner: I see, Mr. Groueff.

Groueff: Groueff. I will tell you what it is about. I am doing the research for a book, which actually has been commissioned by the Readers Digest. I am doing it for the Digest, on the early years of the Manhattan Project.

Wigner: Yes.

Groueff: I have the help of the Atomic Energy Commission and their historian office. And I am seeing different people in universities. But now I am just working on the part about [Albert] Einstein’s first letter, the famous thing. Some very good material I find in this book by the Atomic Energy Commission, “The New World,” then the New York Times published by Ralph Latt.

Wigner: Yes, and that article I have reviewed, and I am in agreement with it.

Groueff: You are in agreement?

Wigner: With the Latt article, I have reviewed, they asked me to review it. I have reviewed, and I am in agreement with it.

Groueff: Yes, that is one of the reasons I’m calling you, to find out whether all the facts are correct.

Wigner: I think they are.

Groueff: Could I ask you a few details? Because I am writing the story and I try to do it for the large public. I am trying to make it very vivid and more colorful. Could I ask you a few questions about yourself? For instance, if you have some very clear recollection of that day, it was the July 30, I think 1939, and it was a Sunday.

Wigner: Yes, it was a Sunday, yes.

Groueff: And the car that you were driving was a Dodge?

Wigner: I think it was, yes, it was my Dodge.

Groueff: I see. Now Dr. [Leo] Szilard and you, you were speaking what, Hungarian between yourself?

Wigner: You know, I do not remember; some things you forget. We usually spoke German to each other. I do not know why, but I am not sure what we did speak.

Groueff: I see.

Wigner: We probably spoke German, because to Einstein we all spoke German.

Groueff: To Einstein you spoke German?

Wigner: Yes.

Groueff: Do you remember where he met you? Was it in a porch of the house, or in the living room?

Wigner: I think we first met in his dining room and then we moved I think to a porch, yes.

Groueff: The conversation took place on the porch?

Wigner: Well, both places.

Groueff: I see. And how long did you stay, more or less, Dr. Wigner?

Wigner: You know, I really do not know, but I would say between one and two hours, not too long.

Groueff: One and two.

Wigner: Surely not longer. Possibly – I am not very clear on that.

Groueff: I see. Probably it was a very hot day; it was in July.

Wigner: It was hot, yes.

Groueff: You do not have any recollection how you or Dr. Szilard were dressed?

Wigner: No, I am afraid not.

Groueff: Yeah, you see these kind of details probably sometimes make it more vivid.

Wigner: More colorful, yes.

Groueff: More colorful. But what would be the kind of conversation you would have with Dr. Szilard during the long hours of the trip?

Wigner: Well, we probably talked about physics.

Groueff: About physics?

Wigner: Yes.

Groueff: You were very friendly with him before, huh?

Wigner: Oh yes, oh yes, he was one of my closest friends.

Groueff: I see. At that time, what age were you, Dr. Wigner?

Wigner: I was born in 1902, so I was thirty-six.

Groueff: Okay, thirty-six. Did you live in Manhattan at that time?

Wigner: Oh no, in Princeton.

Groueff: Oh, you lived in Princeton.

Wigner: Yes.

Groueff: And you worked in Princeton?

Wigner: Yes.

Groueff: And Dr. Szilard, he lived in—?

Wigner: He lived in the Kingston Hotel in New York.

Groueff: I see. So you went to fetch him from the Kingston?

Wigner: No, no, he was in Princeton.

Groueff: He was in Princeton?

Wigner: We called up Einstein’s house, and we found his address there.

Groueff: Yes.

Wigner: And we started from Princeton. It is a very long trip, huh?

Wigner: Well yes, about two hours, three, but that is not unusual.

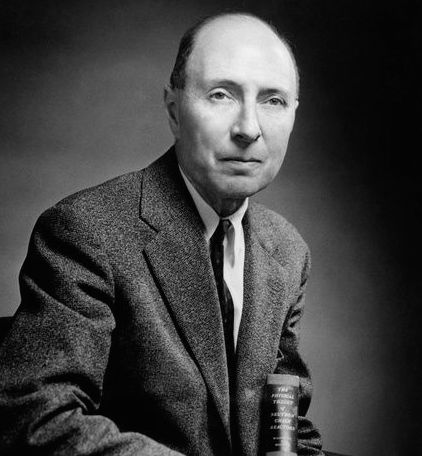

Groueff: And another thing I would like to have about you, Dr. Wigner, is some description of your life and career before that. You said you were age thirty-six. Could you tell me, in a few words, where you were born?

Wigner: I was born in 1902 and I am sixty-two years old. I was born in Hungary and went to high school there. My father was a director in a leather factory.

Groueff: In what factory, leather?

Wigner: Leather, leather tannery. I had an excellent high school into which I went, called Lutheran High School in Budapest. In particular, my mathematics and physics teachers were outstanding people with a true interest both in their subjects and also in the students which they had, I mean, in the pupils.

Groueff: Yes.

Wigner: And my college studies I did at Technische Hochschule. I think you probably –

Groueff: Yeah, in Germany?

Wigner: In Berlin, yes, in Germany, in Charlottenburg, it was called at that time. I studied chemical engineering. But I became increasingly interested in physics so that my thesis, my doctoral thesis, was already borderline between physics and chemistry, and had relatively little to do with engineering. It was rate of chemical reactions. I got in under the influence of a Dr. [Michael] Polanyi, whose name may be familiar to you.

Groueff: Dr. who?

Wigner: Polanyi, P-O-L for Louisiana, A for Alabama, N-Y-I.

Groueff: I see, a Hungarian.

Wigner: Correct, correct, yes, another Hungarian. He is now quite a philosopher.

Groueff: I see.

Wigner: He is in Oxford.

Groueff: He influenced you in your formation and your philosophy?

Wigner: Yes, he influenced me very strongly, particularly, as you say, in my philosophy and understanding of what science is all about, what science is for, how far science can go.

Groueff: I see that you then belong to this kind of scientist who are not only interested in their specialty, but try to see the philosophical, cosmological.

Wigner: Most scientists are. They talk a variable amount about these questions, but most of us are quite interested in broader questions than our specialties.

Groueff: At that time, did you know some of the scientists that later played an important role in the Manhattan Project like Szilard or [Hugh] Taylor?

Wigner: Yes, Szilard I met in Berlin, and we became very close friends. He is perhaps one of the most imaginative people whom I ever met. [John] von Neumann I knew from high school, and I saw him quite frequently in Berlin.

Groueff: Von Neumann?

Wigner: Yes, he was as great a mathematician as we had in the last twenty-five or thirty years.

Groueff: Yeah, I have heard some scientists say that he is a genius.

Wigner: He was. Unfortunately, he died about five or six years ago.

Groueff: I see. Did you meet [Albert] Einstein?

Wigner: Oh yes, oh yes, I met Einstein, [Max von] Laue. Eventually I met all the grand people, [James] Franck even, all the outstanding people. But Einstein I knew reasonably well. Franck and Laue I knew only – I do not think they would have recognized me.

Groueff: But Einstein you knew in Berlin during your student years?

Wigner: Yes, yes, reasonably well.

Groueff: Were you interested at that time in Berlin already in the atom and the possibilities of splitting the atom?

Wigner: No. The atom, you know, atom is a concept which means something different for the theory-man and for the physicist. Atom is the outside of the electronic cell. And of course, the principle interest was in that. What the theory-man now means by atom is what we call the nucleus.

Groueff: The nucleus.

Wigner: There was no real interest in those days in the nucleus. People felt that we must first understand the electronic cell, and that there is a much better chance to understand that. Of course, that was quite true.

Groueff: Yes. What was your main interest, specialized interest in physics that time in Berlin?

Wigner: The rate of chemical reactions.

Groueff: The chemical reactions?

Wigner: Yes, and statistical mechanics. Statistical mechanics, I became principally interested as a result of contacts with Einstein.

Groueff: So you used to see Einstein in Berlin? Was he one of your teachers or just as a—?

Wigner: Well, you see, he was at the university. So formally he was not, but I went to a seminar, which he conducted of statistical mechanics, and I benefitted very much from that.

Groueff: Now when we were talking about your childhood and youth, what kind of family did you come from? You said your father had a tannery, but would you describe it as a middle class or aristocracy?

Wigner: Not aristocracy.

Groueff: It was a middle class, well off?

Wigner: Middle class, yes, well off, well off, definitely.

Groueff: A family with the cultural interests and background?

Wigner: Yes, my grandfather was a physician. We knew only one grandfather.

Groueff: So you had it in the family?

Wigner: Well yes, to some degree. My father became an orphan rather early. In fact, he was a half-orphan when his father died when he was three, and his mother died when he was about twenty-two.

Groueff: I see.

Wigner: He early had to earn his living, very early.

Groueff: So he was, in a way, a self-made man?

Wigner: Yes, yes. Well, the owner of the factory where he worked was a friend of his mother’s landlady. So that helped.

Groueff: But you as a young man, you did not have any problems, material problems, I mean?

Wigner: No, no. I never had any material problems in my life and I do not know what that means.

Groueff: What were your interests as a young man, outside of studying? Did you have some hobbies or music or reading or sports?

Wigner: I used to fence.

Groueff: Oh, like all Hungarians. [Laughs].

Wigner: I was like all Hungarians, yes. I liked to skate, but I did not have any. But of course, I read as most people do, a good deal of literature and [Sigmund] Freud and [Oswald] Spengler.

Groueff: Spengler, yes.

Wigner: But I did not have an outspoken hobby which would have kept me very much.

Groueff: Who do you think were the philosophers or writers who impressed you very much as a young man and left some influence? Spengler?

Wigner: Spengler, yes. But Freud much more.

Groueff: Freud.

Wigner: Yes, Freud much more. But of course nobody of my age group could escape the influence of [Fyodor] Dostoyevsky or [John] Steinbeck in particular, who we were much devoted to, much more than –

Groueff: So they were all slightly on the gloomy and pessimistic side, no, your authors?

Wigner: Yes. You know Hungarians are very fond of jokes, and I love humorous books. I knew by heart much of Mark Twain.

Groueff: What was your attitude to people like Einstein or [Max] Planck? Were they your heroes when you were a student? Or were they on sort of an equal basis, for they were much older men who were already famous?

Wigner: You know, I never coveted fame very much. But of course, I had a tremendous regard for that, and was deeply impressed by their accomplishments.

Groueff: I see.

Wigner: I never considered their knowledge, but greater than knowledge of many other people, and it was. But for their accomplishments, for their imagination, and for what they had discovered, of course I had –

Groueff: Bigger respect.

Wigner: A deep veneration, yes.

Groueff: So when you finished your studies in the university in Berlin, what did you do later?

Wigner: I returned first to Hungary for a couple of years and worked in the same leather tannery then where my father worked.

Groueff: As a business?

Wigner: I was a chemist. After about two years, I received an offer of an assistance-ship from a Professor Richard Becker, at the Technische Hochschule again in Berlin. I was there, then he sent me for a year to Göttingen. Then I became a Privatdozent.

Groueff: In Göttingen.

Wigner: No, no, in Berlin. I returned to the Technische Hochschule Berlin.

Groueff: What year was that?

Wigner: I think I was twenty-six or twenty-five. That means it was around ’27. That is about right, that is right. You can look this up in the American Men of Science.

Groueff: Yes, all this “Who is Who.”

Wigner: Any such men.

Groueff: And then after Privatdozent?

Wigner: The Germans have ranks in great abundance, “nicht beamtete außerordentliche Professor,” but this has not much significance. In ’29, I received a telegram from Princeton University to spend half a year there.

Groueff: Yes.

Wigner: No, it must have been in ’28, because in ’29, the first I spent in Princeton, and then I spent for four years, I believe, four or five years, half a year in Germany and half a year in Princeton.

Groueff: Were some of the European professors already in Princeton, or not, not yet?

Wigner: Dr. [John] von Neumann was. He had exactly the same arrangement.

Groueff: But not [Leo] Szilard or [Edward] Teller?

Wigner: No.

Groueff: Or Einstein or [Enrico] Fermi?

Wigner: No, no. You see, this was still when there was some hope that Hitler would not come to power. I forget when he came to power, about ’32, did he not?

Groueff: Yes, this was much before Hitler.

Wigner: Yes, this was three years before Hitler. The last year it was evident that not much grass will grow for me in Germany.

Groueff: What year did you leave definitely Germany?

Wigner: You know, I do not remember, but I will say ’34.

Groueff: Okay, ’34.

Wigner: It may have been ’33.

Groueff: But was the political reasons important for your leaving?

Wigner: Yes, not important, decisive.

Groueff: Decisive. Were you persecuted, or your family?

Wigner: My mother is entirely of Jewish descent.

Groueff: Yes, so it would be really dangerous for you, matter of life.

Wigner: Oh, I do not know that, but it certainly –

Groueff: Very unpleasant, anyhow.

Wigner: Well I would have been perhaps at most even dismissed from the Technische Hochschule. You remember—I do not know whether you were in Germany in those days—every restaurant had a notice on the door—

Groueff: No, I do not but I remember reading about it, yes. Tell me, was Dr. Szilard of Jewish origin too?

Wigner: You know, I do not know that, and I do not know why I do not know it.

Groueff: But he was a definite enemy of the regime, of Hitler?

Wigner: Oh yes, oh yes. I think probably he was involved in addition to the Jewish, but there is no question.

Groueff: And then you left definitely Germany and went to Princeton?

Wigner: Really not. The situation at Princeton was confused at that time. The number of refugees was very great, as you can imagine. I spent two years at the University of Wisconsin.

Groueff: Did you speak English at that time?

Wigner: Oh, by that time I could speak English, yes.

Groueff: Yes.

Wigner: I must say, those two years got me acquainted with America much more than the full half years or so in Princeton.

Groueff: In Wisconsin?

Wigner: Yes. In Wisconsin I felt at home almost from the first day on, and enjoyed the association with my colleagues deeply.

Groueff: In what town were you?

Wigner: Madison.

Groueff: Which town?

Wigner: Madison.

Groueff: Madison, Wisconsin.

Wigner: Yes, it is the capital. The University is there.

Groueff: And you were a professor there?

Wigner: Yes, a visiting professor, I believe, but all of that did not play much of a role. Yes, at first a visiting professor, then a regular professor.

Groueff: Were you at that time a family man?

Wigner: No. I married a young lady there in this country. She died after about six or seven months of marriage. No, it was a little more than that, perhaps nine months of marriage. That was of course a very terrible thing.

Groueff: So then when the war started, you were a widower?

Wigner: Yes.

Groueff: Did you remarry?

Wigner: Yes, yes, but in 1937, this date I do remember, I returned to Princeton. In 1939, I met my present wife in a summer school at the University of Michigan. And we married, I think, in 1941.

Groueff: Was she a teacher or a student?

Wigner: She was a teacher at Vassar.

Groueff: Oh, at Vassar. And American?

Wigner: Yes, indeed.

Groueff: Then you became naturalized American, or you continued to be—?

Wigner: No, no. I was naturalized even before I married first. I think I was naturalized in ’37. Perhaps, no, perhaps in ’35. I think it was ’35, but you know, I do not keep these dates too firmly in mind.

Groueff: But I can find it in the book. Now when you first got connected with this atomic project in 1939, who was the first one to discuss it with? Was it Dr. Szilard?

Wigner: Who was the first one to discuss it with me? Is that what the question is?

Groueff: Yes.

Wigner: Yes, Dr. Szilard was interested in it already from England on. He had some rather preliminary ideas, and ideas which did not really stand out, which proved erroneous that beryllium would maintain a chain reaction.

Groueff: I see.

Wigner: But when he heard about uranium fission—

Groueff: About the experience of [Otto] Hahn and [Otto] Frisch?

Wigner: Yes, about the experiments of Hahn and [Lise] Meitner – not Frisch, Hahn and [Fritz] Strassmann, but I do not know, this is complex, as you know.

Groueff: I have this story. So he heard of that and he was very excited about it?

Wigner: He at once said, “There is a possibility that this will lead to a chain reaction.” I remember that very well because he happened to be in Princeton, and I was in the hospital in Princeton with jaundice. He visited me every day. When he heard of it, almost at once he said, “This may lead to a chain reaction because the fission may emit neutrons.”

Groueff: So he was the first one to bring you the news, and you were in the hospital in Princeton?

Wigner: Right, I had jaundice.

Groueff: Was he very excited about the whole thing, or enthusiastic?

Wigner: I do not know that, but he certainly saw the possibilities, he was a very thoughtful person and very –

Groueff: Imaginative?

Wigner: Very imaginative, yes. In addition to that, thoughtful also. He realized that every new possibility that is given to man has its dangers.

Groueff: Yes, and he saw the danger of Hitler having this weapon?

Wigner: Yes, but that was of course principle in his mind and he thought about it a great deal. He did not feel that he wants to inform the government, because I am afraid very correctly, he felt that that would lead to a great deal of red tape. That was correct. But on the other hand, you cannot do such a project—

Groueff: Without money and without government, yes.

Wigner: Well, he thought that he could interest private people, and he did. But, in addition to that, it is not the right thing.

Groueff: You joined him in this?

Wigner: I was the one who pressed that we should inform the government. After some time, he consented to that.

Groueff: So the people you discussed it with in the beginning were only Szilard and you?

Wigner: Soon enough, this possibility became generally known. But the initial view of the physicist was against, it was negative. They said, “It will not be possible.”

Groueff: But in your intimate group of friends, who were the other people? Was there somebody else that you discussed it with?

Wigner: Not much.

Groueff: Not much. So Szilard was your friend?

Wigner: Yes.

Groueff: Could you tell me something about Szilard at that time? What kind of a man and where he lived and how he lived?

Wigner: Well he was one of the most independent thinkers whom I ever knew. Very imaginative and very independent in his judgment. If somebody rebuffed him, it did not make any difference to him. That was a very important property.

Groueff: Was he very articulate and brilliant when exposing his ideas?

Wigner: No, no. He was not. In fact, rather the opposite.

Groueff: So, his ideas were brilliant but he was not one of the big talkers and brilliant?

Wigner: No, no.

Groueff: Was he amusing to be with? A pleasant personality?

Wigner: Yes, and you know, the views are divergent on that. I enjoyed his company a great deal. Many people intensively disliked him.

Groueff: What was the main criticism of him? Was he too strong a personality or egotistic?

Wigner: People felt that he was inconsiderate.

Groueff: Egotistical?

Wigner: Well he was, in the American sense, highly egotistical. Egotistical means something different from what the German “egoistisch” means.

Groueff: Not egoistisch, but egocentric.

Wigner: Egocentric. He was highly egocentric. But you know, that is not a fault.

Groueff: No, a lot of great men are.

Wigner: Yes.

Groueff: But he was criticized mostly of not considering the opinions of the others?

Wigner: You know he came to a luncheon and paid no attention to people.

Groueff: Yes.

Wigner: You know, if somebody wants to throw a beautiful party and somebody comes in the middle of the dinner, you can understand that. You understand, it is irritating.

Groueff: Was he what the people usually call the absentminded professor?

Wigner: No, no, he was not. He was inconsiderate, frankly, and he was. But you know, there are these faults fall into insignificance if you compare them to—

Groueff: To his mind.

Wigner: Yes.

Groueff: Tell me about yourself, Dr. Wigner. Are you absentminded?

Wigner: To a moderate degree, I would say. My wife would know that better.

Groueff: I never met you unfortunately, but you are not an extrovert man, no?

Wigner: No, I am not an extrovert.

Groueff: You are a rather calm man and modest.

Wigner: Calm? I do not know. But certainly Szilard was extremely lacking in modesty. But you know, all these things are not—if you compare them with real faults such as selfishness.

Groueff: Those faults make the personality more colorful, but not necessarily a worse—

Wigner: It would be lost.

Groueff: Was he a man who had the big tempers and shouting and that?

Wigner: No, no, never.

Groueff: Never. Anything particular in his dressing or in his habits?

Wigner: He was a little carelessly dressed.

Groueff: Carelessly dressed. And smoking or drinking?

Wigner: He did not smoke. I do not remember that he drank.

Groueff: And you, what kind –

Wigner: I do not smoke, but I like a glass of wine.

Groueff: How are you dressed usually, Dr. Wigner? Are you on the conservative side?

Wigner: Yes, I think so.

Groueff: After all these conversations with Szilard, you decided to go to Peconic [New York] to meet Dr. Einstein?

Wigner: I said I would like to write a letter—no, that was his idea. I said I would like to write a letter to the government or to the people who are in charge of such matters. And Szilard said, “Look, if we want to approach the government, we should do it in an effective way, and let us have Einstein write a letter.”

Groueff: Did you contact Alexander Sachs, or was he a contact of Szilard?

Wigner: We both knew him, but since Sachs was in New York, I choose that Szilard took the letter to Sachs.

Groueff: Do you think that Sachs originated the idea, or Szilard and you? Or both at the same times in different ways?

Wigner: I never heard about Sachs proposing this. But you know, I do not know, these are not discoveries on which one keeps priorities.

Groueff: Oh yes, everybody works in different fields, because I know that Sachs was talking already to the President generally about using scientific discoveries in the war. So probably your and Szilard’s idea came just at a good moment.

Wigner: Quite possibly, yes.

Groueff: So he drafted this letter?

Wigner: No, no, Einstein drafted the letter.

Groueff: Einstein did?

Wigner: Einstein on his spot dictated the letter and I put it down on paper. I was amazed how he could dictate a letter without preparation and without going back, “Now, that sentence I want to change,” and so on. He really dictated the letter.

Groueff: I see, yeah, because that is a point. I read several descriptions and they are all very different. The description from Sachs was that he and Szilard prepared sort of the draft, and you brought it with Szilard, then Einstein read it, probably the three of you made some changes or corrections.

Wigner: I do not remember any of that. I may be wrong.

Groueff: Then there was a second visit by Szilard and [Edward] Teller.

Wigner: I understand there was. You know, that escaped my memory until recently.

Groueff: Because you were busy that day so he had to take Teller to drive?

Wigner: I do not know.

Groueff: But tell me, you drove the car?

Wigner: Yes.

Groueff: It was your car?

Wigner: Yes.

Groueff: I see. And what else I wanted to ask you?

Wigner: The address was given to us by Ms. [Helen] Dukas. And we first misunderstood it, because, you know, it is an unusual name, Cutchogue. And then we looked at the map, we found Patchogue. And we thought we misunderstood, and that it is Patchogue.

Groueff: Who gave you that first address, you said?

Wigner: Ms. Dukas.

Groueff: Dukas, that was –

Wigner: The secretary of Einstein.

Groueff: The secretary of Einstein. On the telephone?

Wigner: Yes.

Groueff: And you started from Princeton, and Szilard came first to Princeton?

Wigner: We were both in Princeton and we phoned Ms. Dukas.

Groueff: Where did you live at that time in Princeton?

Wigner: At 120 Prospect Avenue.

Groueff: At 120 Prospect Avenue. Did you have children at that time?

Wigner: No, no, you see I was not—

Groueff: Ah, that was ’39.

Wigner: Yes, I had no children from my first marriage.

Groueff: You were a professor at Princeton then?

Wigner: Yes.

Groueff: After the letter, in the year 1940, you participated in some conferences with government people, with the Briggs Committee?

Wigner: Yes, yes.

Groueff: But you continued to be a professor at Princeton?

Wigner: Right, right. At first I felt it may be better if I do not participate in the work, because I did not want to get into completion with Szilard. But it soon became evident that I do much more good if I do participate in it.

Groueff: Yes.

Wigner: And Ed Creutz, C-R-E-U-T-Z.

Groueff: Creutz, yes.

Wigner: And R. R. Wilson.

Groueff: Wilson.

Wigner: And Thomas Snyder, S-N-Y-D-E-R.

Groueff: Snyder, yes.

Wigner: Started a small project in Princeton, which the reserves of which proved very useful later on. Very useful.

Groueff: In what field was that?

Wigner: That was in the—well, I do not know how familiar you are with the subject in resonance absorption.

Groueff: But it had to do with the Manhattan Project?

Wigner: Oh yes, there was no Manhattan Project then. Yes, it was uranium.

Groueff: Uranium.

Wigner: Yes.

Groueff: So you worked on uranium, but later did you not work in the plutonium thing in Chicago?

Wigner: You see, the plutonium is made by having achieved reaction with uranium.

Groueff: Yes, but the reactor in Chicago, you worked on that too?

Wigner: Yes. This was one of the elements that was necessary to know before the reactor could be built.

Groueff: Were you working with Fermi at that time?

Wigner: No, Fermi and Szilard to some degree worked together in New York, and to some degree, separate. I think you probably know that [Herbert L.] Anderson and [Walter] Zinn are two of the collaborators.

Groueff: Yes. And later, Compton.

Wigner: Compton came in on Pearl Harbor Day, so to say.

Groueff: Yes, and they moved the whole thing to Chicago.

Wigner: Correct.

Groueff: And did you move with them?

Wigner: Yes. I think we moved about the first of April.

Groueff: So in 1942 – that was December ’42?

Wigner: In ’43 we moved to Chicago.

Groueff: And you lived in Chicago then?

Wigner: Yes, for about three years. I think we moved back almost on Pearl Harbor Day.

Groueff: You stayed there until the bomb?

Wigner: Yes.

Groueff: You did not work at Oak Ridge or Los Alamos?

Wigner: Not at that time. I visited Oak Ridge several times, but I did not visit Los Alamos until after the war.

Groueff: And did you go to Hanford in connection with –

Wigner: Yes, I was once in Hanford, but it was not significant.

Groueff: So your main job was in Chicago?

Wigner: Yes. We designed the Hanford reactors, the theoretical physics group. I was the leader of that. Designed the Hanford reactor, which was then built by the DuPont Company. But of course, the detailed design was done by DuPont. But we reviewed all the drawings which were pertinent. That was our principle job in Chicago, after we had designed the Hanford reactors in Princeton.

Groueff: So you worked mostly with the group of [Arthur] Compton, Fermi, Zinn?

Wigner: You know, not, because Compton was the director of the project. You did not see him terribly much. Fermi worked on the experiment establishing of the chain reaction. We worked on the design.

Groueff: Of the real one?

Wigner: Of the production reactor.

Groueff: But was not the pilot reactor built first, or to be built in Oak Ridge?

Wigner: It was built. But that was designed by one of the collaborators, who is now Director of Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Alvin Weinberg. Took him probably two weeks to do it. You see, we had all this under control, and we could design low power reactors at the drop of a hat.

Groueff: But the big reactor in Hanford was designed by you and your group?

Wigner: Yes. Weinberg was a member of that group, and once he took off two weeks to design the reactor here.

Groueff: Who were the members of your group who designed the Hanford?

Wigner: There were several, about ten or twelve people, but the principle ones were Alvin Weinberg, whom I mentioned, Gale Young.

Groueff: Jung?

Wigner: No, Young, like a young man.

Groueff: Ah yes, young.

Wigner: And O-H-L-I-N-G-E-R.

Groueff: Yes, [Leo] Ohlinger.

Wigner: These were the principle, and I cannot enumerate the rest of them.

Groueff: And yourself.

Wigner: And myself.

Groueff: You were the sort of the chief of the project of this particular group?

Wigner: Yes, I was the head of the group.

Groueff: Who was your sort of direct superior?

Wigner: My superior was Fermi, but he did not interfere at all in the work.

Groueff: Did you have to work with General Groves? Did you have contact?

Wigner: I knew General Groves. I saw him several times. Frankly, of course, often I was terribly irritated by him. But in retrospect, I must say that he never told me a falsehood, and that is more than I can say for many other people.

Groueff: He must have been a very strong and rather difficult man if you are nothing, in his kind of –

Wigner: Yes, I think that is so, but he was honest.

Groueff: Honest and open.

Wigner: And open. As I said, he never told me a falsehood, which means something.

Groueff: Yeah, why do you think most scientists were irritated by General Groves? What side of his character or behavior was most criticized?

Wigner: He did not, of course, understand what science is. He was distant. He maintained strict security, the purpose of which we did not understand.

Groueff: Yes, but in his relationships with the scientists, was he polite?

Wigner: Yes, he was. He cultivated them. He was not at all—

Groueff: He was not shouting, giving orders?

Wigner: No, no. He was a soldier, of course.

Groueff: So could you describe it as sort of—he was polite, correct, but distant and cold?

Wigner: He was not even very cold.

Groueff: He was not, okay.

Wigner: No, no, no. You see, in retrospect, these things change a little bit. For instance, we did not agree with his choice of DuPont as contractor. And we felt that he did not listen to us when we advised him to do otherwise.

Groueff: Because you wanted to build the whole thing, the Hanford reactor, to be built by Chicago group?

Wigner: Well, no we did not go that far, but we thought it would be better, first of all, if the collaboration is much more intimate. You see, the DuPont first did not know what it is all about. Fermi always started his discussions with, you know, “The neutron is a tiny particle.” We hoped we would get some people who knew already that the neutron is a tiny particle.

Groueff: Yeah, but as you say, when you look back, do you think that he was a good man for the job?

Wigner: I think rather good. I do not think he was unique, but I surely do not have any grudge against him. In retrospect, I think he was as good as we could expect. You see, I am not enthusiastic about it, but I am sure we do not think—

Groueff: How were the relationships of the scientists and of your group with Dr. Compton?

Wigner: Very good, very good, yes.

Groueff: And with Fermi?

Wigner: Excellent, excellent. Well, Fermi was one of us.

Groueff: So it was in Chicago that the relationship between the scientists was very friendly and good?

Wigner: Yes. There were some difficulties in the chemistry division, but nothing in the physics division, nothing.

Groueff: Sometimes there are a lot of jealousies and personal intrigue. Like I understand in Columbia, the atmosphere was very bad.

Wigner: I heard some thing or other, but there was nothing of that in Chicago.

Groueff: I see. Well, it was very kind of you, thank you very, very much Dr. Wigner.