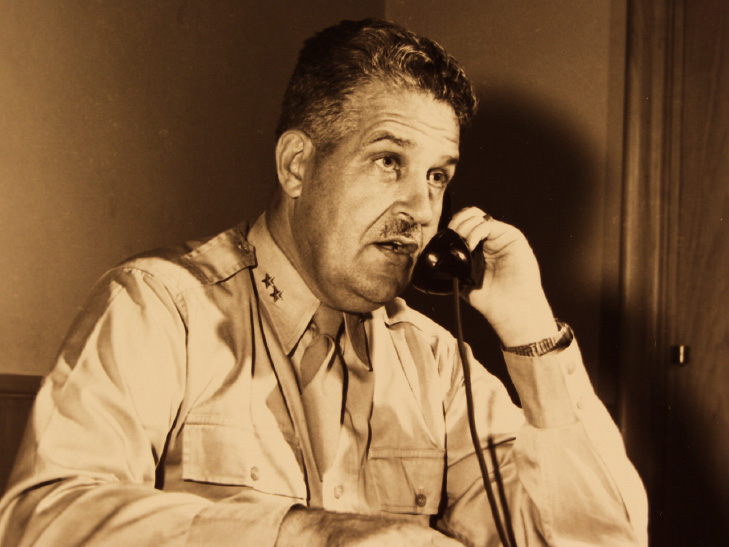

[We would like to thank Robert S. Norris, author of the definitive biography of General Leslie R. Groves, Racing for the Bomb: General Leslie R. Groves, the Manhattan Project’s Indispensable Man, for taking the time to read over these transcripts for misspellings and other errors.]

Stephane Groueff: Now I wanted to ask you, General, a few personal questions about your background, about your life, about your childhood, your education.

General Leslie Groves: Well, you can start right off.

Groueff: And as the Groves family, I wanted to ask you, you told me that you have––

Groves: Yes.

Groueff: This book list. I have the facts of your career, who is who and press releases. I would like something more about your formation, about your way of thinking, your education. So could we start from the beginning? You were born in Albany. You were son of a—

Groves: I was born in Albany, New York, August 17th, 1896. I was a junior. My father was a Presbyterian minister who had the Sixth Presbyterian church in Albany. He was brought up on a farm. He was born in 1856 about eight miles outside of Utica. As a farm boy, he was the first one of his family to receive higher education beyond a preparatory school level. And he went to Hamilton College, which was not far from his home.

After graduating from Hamilton College in 1881 he spent the year, I believe, teaching school up on the St. Lawrence River. Name of that town was— I do not know at this time.

He then studied law in Utica in a lawyer’s office and was admitted to the bar by the Supreme Court of New York State in 1884. After practicing law for a few years, he then entered Auburn Theological Seminary and graduated from there in 1889. He was then at a small church in McGrawville, New York and from 1889 to ‘91 and then in Albany from ‘91 to ‘96. On December 28, 1896 he became a Chaplain in the Army.

Groueff: The year that you were born.

Groves: Yes. As a matter of fact, he had been asked by the Secretary of War, the then Secretary of War, Mr. Daniel Lamont of the Cleveland administration, a number of years before to become a chaplain. But he had turned it down and then apparently Mr. Lamont came back and more or less insisted. Mr. Lamont knew him very well, as I think he came from McGrawville. My father served first at Vancouver Barracks where the 14th Infantry was stationed.

Groueff: Where is the Vancouver Barracks?

Groves: Right opposite the Columbia River from Portland.

Groueff: I see, it is in Canada.

Groves: No, Vancouver, Washington.

Groueff: Oh, Vancouver, Washington, I see.

Groves: Yes, it is a town across the river from Columbia. And Vancouver Barracks was an old frontier post that had been sort of a headquarters for all the control for the states of Washington and Oregon.

My father went to Cuba in 1898 with the Eighth Infantry and then returned from there. He had yellow fever down there and came back in very poor physical shape. He went with the 14th to the Philippines and joined the 14th Infantry there, and he was there in 1900 and 1901. And he also was a member of the 14th Infantry in the Boxer expedition to China.

I think that about does it. As far as his father was concerned, he was born in Massachusetts at Brimfield, which is not far from Sturbridge, a few miles. And then he left there and moved over to near Utica.

His father was also in Brimfield, born in Brimfield, I believe. Let us see, hundred and seventeen. His father was born in Brimfield in ‘72. And he was a farmer all his life as was my grandfather. He always lived at Brimfield.

Groueff: So who are the people from—of moderate condition, farmers or wealthy or—?

Groves: Well, my grandfather had quite a large farm but I would imagine you would call him a prosperous farmer, with a number of hired hands and all of that.

Groueff: I see.

Groves: But of course, life in this country was very simple and they did not have the things that we have today, by any means, so that you just cannot tell.

Groueff: Yes.

Groves: Peter Groves, who was born in 1739, ‘66, was a soldier in the French and Indian War and took part in the Battle of Lake George, which was against the French. He was also a soldier in the American Revolution and was one of the original covenant signers. They were the ones who signed covenants not to buy anything from Britain at the time of the—any imported goods. His father was Nicholas Groves and he was born in Beverly, Massachusetts. The family before that all lived in Beverly. And he apparently was what was known as a husbandman and a prominent man of the town. He moderated the town meeting, members of the board, a selectman, an assessor, treasurer.

Groueff: What do they call them? Husbands?

Groves: Husbandmen.

Groueff: Husbandmen.

Groves: Yes. And he apparently had money because when he moved, when he went to Brimfield, he purchased there several tracts of land containing 101 acres for 300 pounds sterling. And you see, when I speak about him being prominent, it was in Brimfield. His father and the first three generations were in Beverly, and his father was Peter Groves, who was a mariner by occupation, likely a sea captain. And he had various town offices of one kind or another and is what is called a freeman and held a freehold estate of 300 pounds. And his will was given incompletely here.

His father was the son of the original one and he was—the original one was Nicholas Le Groves, who apparently he came from the Isle of Jersey to Salem before 1668. I would guess that that he had jumped ship as was the custom then. Just when he came, what his age was, I do not know. His original name apparently, I would guess from things I learned later about the Isle of Jersey, was Le Grove, which is a very common name in Jersey.

Groueff: So half French?

Groves: Well, he was Jersey, so he was all French.

Groueff: All French.

Groves: And he was a French Huguenot without any question. He had the name Le Grove, Grove, and Groves. His son, some of his children had peculiar names. One was a daughter was La Groves. A son was La Groves. That is the one that started off, no, then another daughter was La Groves.

Then a son who in my line was La Grove, another son was Lagro, L-A-G-R-O, which would lead me to believe that the Lagro guess was right.

And then there was another daughter, Lagroe, L-A-G-R-O-E. And this ancestor, apparently in 1668 he was one of the citizens who signed a petition against imposts to the general court of Massachusetts Bay Colony, which indicated of course that he came there some time before that. Just when we do not know, although they think he was born about 1645. But I think that is a little late to have it. I think it was probably earlier than that.

He married the daughter of—I will just read it. He married Hannah Sallows, born in ‘54, the daughter of Robert and Freeborn Sallows. And she was the granddaughter of Sallows of Salem in 1635, also granddaughter of Peter Wolfe, a freeman of Salem in 1634. And Wolfe was a sergeant and then he was appointed a lieutenant of a trained band of soldiers. He with his wife Martha were founders of the First Church of Beverly in 1667. The church is still there but it is a new building. It is still a very old building.

He was of French origin. His name appears on a list of the French Protestant exiles born “In Partebus Transmarinis” and represented as living in the colonies. They were naturalized by Royal Letters Patent, Westminster, 1682. He was an early settler of Beverly, Mass, where he purchased in 1685 with John Black, a carpenter, in consideration of the sum of twenty and five pounds a certain parcel of upland and meadowland containing four and one half acres, and so on and so forth.

He was a seaman and likely a sea captain engaged in colonial trade with the West Indies. It appears that he spent very little of his time at his hometown. His family soon became members of the Beverly First Church, his wife being one of the first members. I think that is about it.

There was one here who had a very wealthy member of the family that lost all of his money in the Revolution fitting out privateers, none of which were successful. [laughter] Just he was a, I guess, a grandson of the original one. Captain Freeborn Groves. He is educated in England and having a large estate which he inherited from his father, see who his father was. His father was also a sea captain. He is the one who left a long will. But this one, he is educated in England, and being well-known in Massachusetts entertained extensively. He had his Negro servants born on the homestead, all bearing the name of Groves, possibly some slaves.

The first private carriage in Beverly was imported and used by Freeborn. The Revolutionary War was ruinous to him. He refused all the tempting offers made him by Governor [Thomas] Hutchinson and other friends and threw his whole heart and means into resistance to British. He lost two of his own ships, one being captured by the British together with half of his fortune, which he was bringing over from England in there. Later he mortgaged his estate and raised money to fit out a ship with which to make reprisals on the English. Finally, he went down on board of a prize he had taken was himself bringing in, although all his crew were saved. And that was right in the center of town. And they even went so far as to have a coat of arms. [Laughter] I think that tells you the—

No, I think the other thing—Mrs. Groves said to tell you, if you wanted to know what it was and so forth enabled me to do what I did, it was because I had the same ideas and ideals and principles as people who founded this country.

Groueff: That interests me, really. I want to find out what made you the man you are, the way you think, the way you act.

Groves: Well, I would say that we were—my brother and I were talking about it—

Groueff: You had a younger or older brother?

Groves: I had two older brothers, one of whom died when he was about twenty-two [Allen]. He was a very brilliant student and he had done at Hamilton College just about what [General Douglas] MacArthur did at West Point, as far as standing one and everything. He selectedhis subjects on the basis of a lot of money prizes at Hamilton. He always selected subjects on which had the best money prize. [Laughter]

Groueff: And he won them all.

Groves: Oh, he would take a lot of prizes at Hamilton. And oh, he started off with an entrance examination where I think he won that and got a—I think it was 100 dollars plus free tuition for four years. He did very well. But he got an overextended heart and died here in Washington in 1916. My second brother is still alive, and you might talk to him.

Groueff: Yes, I would like to.

Groves: Yes, and although he retired finally from Adelphi College, he is still teaching there this year after one year being away. We were talking about it and he commented on the fact that—he said that he thought we were very fortunate in our upbringing because we were brought up in an educated cultured family that was not interested in anything except in what might be termed “the better things in life.”

My father was away from home a great deal. I did not know him. First time I saw him to know him was in 19—that is, to remember him, was when I was well over five.

Groueff: Where did you live while he was traveling to Cuba or China?

Groves: We were at Vancouver Barracks.

Groueff: Vancouver Barracks.

Groves: We stayed there the whole time.

Groueff: Your mother and the three boys.

Groves: Yes. And then 1902, I had a sister [Gwen] born who died last year. But my mother lived there throughout that whole period, which was customary in those days because the Army was small and when an officer went overseas, why, it was quite customary for the family to remain in the quarters that he had.

Groueff: What kind of quarters? Were they in the barracks area?

Groves: No, no, they were—Vancouver Barracks at that time had a typical officer’s line. It would be on one side of the Parade Ground, if this is the Parade Ground, on this side would be the officer’s line on this side would be the barracks. And ceremonies and drill were all out in this very large Parade Ground.

Groueff: In between.

Groves: Bigger than anything that you would see in France, I would guess. And the officer’s line stretched along here, just one long line of houses.

Groueff: Small houses, individual houses?

Groves: Well, they were mostly—a great many of them were double houses.

Groueff: So you were brought up mostly by your mother the first five, six years.

Groves: Well, for the first five and a half years, my mother alone. Then when my father came back. We were then at Fort Snelling at Minneapolis in St. Paul, Fort Wayne, Michigan which is right in Detroit, and then at Sandy Hook at Fort Hancock.

Groueff: And you followed, the family followed?

Groves: The family was alone then.

Groueff: Yes.

Groves: And then my father got tuberculosis and was sent to Fort Bayard, New Mexico, which was in Silver City, which is the old tuberculosis hospital of the Army. And it also was the general hospital; they took Navy as well, although it was Army run. Then that was in 1903, I think. He went to New Mexico.

Groueff: You followed him?

Groves: That would probably have been in 1904. In 1905, for some reason my mother wanted to get away from Sandy Hook, I think because the environment was strained. We were not with people that we—there were not old friends there.

And so the 14th Infantry, in the meantime, had come back from the Philippines where it had been sent, and it was stationed at Vancouver Barracks. And some way my mother got assurance that if she would come out to Vancouver Barracks that they would give her quarters in anticipation of my father’s rejoining the regiment. This we did. We moved out in 1905 in the summertime. And then we lived there for a year. Then my sister became ill with a bad back, a tubercular back, and it was felt wise to take her to California both for examination and for treatment. And at that time there were very few specialists in this area, and one was in Los Angeles and one was in San Francisco.

And so we moved from Vancouver Barracks. By that time also it had become evident my father would not be rejoining the Regiment in any reasonable length of time. So we moved to Pasadena and where my father came over on sick leave,from Fort Bayard. We lived there in Pasadena, this was in July of ‘46 [meant to say ’06] or June of ’46 [meant to say ’06] And we lived there from then on.

Groueff: 1906, you mean.

Groves: 1906. Then in 1908, my father was allowed to leave the hospital, I believe it was in 1908, and was stationed at Fort Apache, Arizona, which was sort of a convalescent duty, you might say. In other words, the doctors felt that he could perform that duty perfectly satisfactorily, and that with time they could then decide whether he could go back to join his regiment no matter where it went. So 1908 until 1911 at Christmas he was stationed there.

I spent the summer—I spent about six months of 1908, I think starting in May and winding up in November, with him over there. My mother and sister were there for up until about September, and then I was there alone. I would have stayed there. I went to school there in a post-school taught by a Corporal, I believe, one-room schoolroom not much bigger than this room.

The teacher was a very good teacher. He had about a year and a half to two years of high school, which of course meant a great deal more than it does today. And he could teach all the subjects. I was then in the sixth grade. If I had stayed, I would have finished the eighth grade that year.

Groueff: The first five grades you took in Pasadena?

Groves: No, I had taken—go back. I had taken the fifth and fourth grades in Pasadena, the third grade in Vancouver, and the second grade in a one-room schoolroom at Sandy Hook, New Jersey. It had one of those hot stoves in there. I think I was taught privately for the first grade. That is, my aunt who lived with us most of the time ran a little post-school for children they could not get into town.

Groueff: Your mother’s sister.

Groves: My mother’s sister. Then they had maneuvers and the troops left for Apache and took my schoolteacher with them and my father sent me home. [Laughter] And I then went to a school in Altadena, which was just north of Pasadena where we really lived, it was in Altadena. And after the first six months we moved and bought a house and lived in Altadena.

So I went there for the remainder of the seventh grade and the eighth grade. And then to Pasadena High School for a year and a half. And then in the summer of 1911 I spent the summer with my father in Arizona. He would come home on leave from time to time, but of course the leaves were only a month a year, you see. But so essentially you might say we were brought up by my mother.

Groueff: What kind of a woman was your mother? Strict?

Groves: Just like any normal mother of that day was.

Groueff: You were very influenced by her?

Groves: Well, I imagine so, and also by my father. And I never heard one single word of dissention between my mother and father at any time. I never got any feeling of anything, excepting my mother once said she bought some land next to our house and she had money enough in the bank to buy it and pay cash for it. And she said, “You know, I don’t think your father would like this.” And the reason that she said it was because there were some friends of ours that wanted to buy it. But that would have jammed everything up too tight and we just did not want them there, my mother did not. And this you cannot mention because my sister later married the son of that family. So you have got to leave that out. [Laughter]

My mother was a great card player, as was my aunt. My father said that the card playing was a waste of time, but that was all that was ever said.

Groueff: What did they play at that time, bridge?

Groves: No, I guess they played straight bridge and a game called 500 a great deal. And I think that was essentially it. As a result of that, I was always a very good card player.

Groueff: Since your childhood.

Groves: But I do not play anymore. I stopped playing because my wife is a terrible one, hated it. And I did not like all this introduction of rules.

Groueff: What is your game, bridge or poker?

Groves: No, I did not play—I do not play anything, just too much—I do not have the time.

And I just figured that so long as she did not like to play and as long as they were starting all of this playing by rules, I was not interested. It ceased to be a game then and became just, what is the rule for this and the rule for that.

Groueff: Was your mother an educated woman?

Groves: No, no, she was—I think all girls of her time, I do not know just how far she went in school. As far as I know, did not go anywhere.

Groueff: Your aunt was more educated?

Groves: No. The average girl of that period—her father, my mother’s father, was in the Civil War. He had been a prisoner of war at Andersonville and at Libby prison for about two years, I guess, or more. His whole Regiment less a Company was captured in the West. And like all men who went through that prison privation, and it was particularly worse than anything that we read about in this war and the Germans and the Japs and everything else, because the South just did not have anything to give them, you see. Was not a case of starving them deliberately, it was a case, “Well, we do not have anything.”

Groueff: They could not give you—

Groves: “We cannot give you what we do not have.”

The result was that he ran a general store in a little town called West Winfield, about twelve miles from Utica and then the family moved into Utica. I think that he just was a complete failure.

Groueff: Your grandfather?

Groves: Yes, because my father told me something to that effect, he implied it. And he had been like so many men who have been prisoners. MacArthur told me once, he said, “You know, no man was ever a prisoner ever amounted to anything afterward excepting our few that were captured in World War I at the tail end of the war.” And of course in Korea, there had been a few exceptions to that, but very few. I think the present chief of staff of the Army was a prisoner in Korea or a prisoner against the Japanese. But only people who were very young when that happened and who had not gotten anywhere. There have been a very few rare exceptions. But there is something about prison life that does the trick.

In any case, I would say that there was, and I believe that my grandmother actually ran a sort of a boarding house there in Utica to support the family. My grandfather did not live too long. I do not know just when he died. I never knew any of my grandparents, either my grandmothers either. He was Welsh, born in Remsen, New York, shortly after his family got there. My mother’s mother was born in Wales. And she had some very well-to-do Canadian cousins who ran a flour mill at Guelph, Canada, that has now been amalgamated with various other things.

Groueff: So you are half Welsh?

Groves: Yes, half Welsh. All the other ancestry is English straight through, excepting for the original French. Well, there may have been a little here and there, but none that we know about.

Groueff: So the atmosphere at home wasn’t the kind of intellectual or books?

Groves: Oh yes, because that is what people did in those days. And the discussions at the table were always uplifting.

Groueff: They were between what? Your mother, your aunt?

Groves: No, it was between the children and my father and mother, my father if he was there. And it was grownup conversation. And of course at first you listened, and then gradually you started to take part in it. But for example, I understood the Stock Market and various types of securities when I was twelve. [Laughter] My oldest brother used to read the almanac, for example, and I was always trying to keep up with him, of course, when I was five years old.

Groueff: The Farmer’s Almanac?

Groves: Oh no, the World Almanac, oh yes. We could have told you, he could have, the largest hundred cities in the United States with their population, everything else. All the succession of presidents and vice presidents.

Groueff: What kind of boy were you? What were your main interests in playing? Sports or reading books?

Groves: I would say that just what the average boy was of that time. We all had work to do. Of course, on a Post you could not do any work, really. But even though at Fort Apache I took care of our horses and our chickens, which—in the garden, which we had to have or we did not eat anything except in canned goods. I was the assistant milker of a cow and my sister was there. We would borrow a cow from a cattle ranch, you see, beef cow.

Groueff: Where?

Groves: In Arizona. And then the calf would come along with it. The cows would be turned out to graze in the daytime, Indian boy would come along and pick him up. We had a private stable. There were very few. There was only one other along the officer’s line, but a lot of the civilian employees and enlisted men had cows that they borrowed the same way from a cattle ranch. And the calf would be penned up during the daytime. The cow would come home and would be turned loose by the Indian boy outside the gate. And if I was there it was very simple, but if I was not there the cow would start to wander and she would wander all over the Post. I would have to then go out and chase her in, always of course on horseback because we would not think of walking. And you would get the cow in, and the calf would be tied up and you would tie up the cow so that the calf could not get at the cow.

Then my father would milk her. And he always would milk into lard buckets which were the famous—they were most the used cooking utensil in the West at that time. People made coffee in them, they would do everything, boiling. And the lard bucket of that time was normally about two or three pounds, about that high, about that big around, could hold, well, maybe two quarts at the most of milk. And I would stand at the head of the cow and try to keep the cow amused. [Laughter] My father would do the milking. And after it had progressed a certain distance I would then tell Father, “Well, you had better start on a new bucket because that cow is getting ready to kick.” Well, he would always insist that he could get more in and quite often the cow would kick. [Laughter]

And of course there was never any profanity used in our house of any kind. Father would merely say, “Well, you are not keeping it very well amused up there.” [Laughter] And I tried to get him to let me do the milk, to learn to milk, but he said, “No, they never gave a new milker any chance to milk until the cow was ready to dry up.” He said that was an old custom because he said, “You dry up a cow if you do not milk properly.” Well, so I never learned to milk.

Then after the cow was milked we would turn her loose with the calf, and the calf would have the milk all night and then next day she would start to make milk for us. And I took care of two horses. The garden was of considerable size. But—

Groueff: You could ride on horseback since you were a child.

Groves: Well, I started to ride when I was ten years old. We had a horse in Pasadena.

Groueff: And you were quite good? You liked that?

Groves: Oh, I was a good rider. And I liked it very much until I got to West Point, and there with the instruction in riding I decided I did not like riding anymore. [Laughter] I was always a good rider but I just did not like what they did. I wanted to ride. I did not care much about jumping, which of course they do at that time.

Then of course in California we worked in the summertime from the time I was eleven. I did not do much when I was ten. My father had said I was supposed to help, but I did not do much. And I really did not get started working, I would say, until I was over ten. And I think the first venture was picking English walnuts. We had some enormous trees and quite a crop. I was amazed.

When my sister was so sick this last January I ran into an old friend of hers and she says, “Oh, I remember you very well. We were in the fifth grade together, the fourth grade together.”

I says, “What?”

And she says, “Yes,” and such and such at school. “I always remembered you because any time a question was asked your hand would always shoot up and your hands were just stained so deep brown with that walnut husk that I’ve never forgotten you.” [Laughter] I was amazed. Of course I had no idea.

We walked to school, of course. First place we lived was about a mile, we came home for lunch. And then we moved and it was too far to come home for lunch. It was about somewhere over two miles. I do not know.

Groueff: And you walked?

Groves: We walked both ways. And carried lunch in a paper bag because we did not want a lunchbox because then you would have to carry it home, you see.

Groueff: Were you a healthy boy? Strong?

Groves: I would say that I was healthy from the time I was about six or seven. They tell me that I was sick quite often before that, but I think that is generally true.

Groueff: I see. Were you very strong boy or resistant?

Groves: No, I would not say particularly

Groueff: Running into fights or sports?

Groves: You see, sports in those days were—then I started picking fruit the next year. And unless I went over to Arizona I would work during the summer picking fruit: prunes, apricots, peaches, and grapes. And you could do pretty well at everything but grapes. You would make normally about a dollar a day. I know on one day I made a tremendous record and made $2.50 in picking peaches. You would shake the tree and pick them up off the ground. They were all for [inaudible].

But grapes you had to work like a dog for at least ten hours to earn as much as sixty cents. The reason why is the competition was set by Mexican labor. Our grapes were just like they are in Europe and California. And they would load a box weighing fifty pounds and carry that box out. We could not. We had to use coal hods. And we would pick into those. So that meant we made one extra trip. You see, for every box we made two trips, the Mexican would make one.

But grapes did not bring much. They brought six dollars a ton at the winery. They had to be hauled by team about two miles, I guess. And the picking cost, you see, at three cents a box would have been six cents a hundred, or a $1.20 of that six dollars went to the pickers. And then there would be a boss for the pickers who got paid and then the teaming and all the rest of it. Did not leave anything for the grower. Of course that land now is all—the same grapes now bring around 70, 80, 120 dollars a ton.

Groueff: Did you work after school hours?

Groves: Not at that. During the summer. That was when the picking season came. In the Wintertime I worked on our place, which was an acre and a half of highly ornamental—

Groueff: Flowers.

Groves: Not flowers so much as trees and bushes, and of course they all had to be irrigated during the summer months. I did quite a lot of work on the place and did a lot of things, such as I became quite proficient with an axe and a two-man saw. I used to use a two-man saw by myself. [laughter] And the axe I did very well after an early experience when I sliced my foot open in a brand new pair of shoes, which I remembered always because I persuaded my mother to let me buy some—to buy me some light buckskin shoes that were sort of a light cream color. And this axe slipped somehow, I do not know what went wrong. But anyway came right down on my foot, cut right through the eyelets in the shoe, went right through to the bone, cut it about that long. And to show you the difference in time, what is done today and what was done then, there was a registered nurse who had not practiced, who had gotten married and had gone out of practice, lived across the street. She came over and bandaged it up and dressed it for me.

Groueff: Such a heavy cut.

Groves: No doctor, nothing else of any kind, because people did not use doctors in those days. Today they would have given me tetanus shots, they would have been—oh, they would have taken stitches, would have been a great to-do about it. But as it was, I just sat there while she stopped the bleeding, soaked it in a pan of warm water, and bandaged it up. Of course I still have the scar. It is about that long.

Let me see, what else would be of interest to you.

Groueff: Was it a religious family? I mean, your father being a chaplain, obviously he was a religious man. Your mother, too?

Groves: Oh yes.

Groueff: And you, too, the children used to go to church?

Groves: Oh yes, always went to church. We went to Sunday school and we went to church. And of course when we were on the post, why there was normally one service on Sunday plus the Sunday school which we went to.

Groueff: You were Presbyterian?

Groves: Yes, Presbyterian. And I would say that of course there was another thing, that my father was older than, let us see, he was forty when I was born. But people in those days respected their parents, nothing of this business thinking that anything your parent did was wrong or stupid or anything like that. Nobody was telling him what to do. If he told you how a horse was to be groomed, you groomed it that way. And there was not any thought about, “Oh why do I have to groom that horse, why do I have to groom it because it is just going right out in the stable yard and get all muddy all over again?” There was nothing of that kind.

In Arizona I did the cooking, when we were alone I did the cooking for us for about two months. We started to eat in a Chinese restaurant where the bachelor officers ate and my mother—that is, when my mother was not there. And I ate lunch and dinner there and my father ate dinner there. And we did not mind having flies on the steak that had been broiled [laughter] because you picked those off if there was a fly in the middle of the bread [laughter]. I said to father, I says, “Well, let’s stop going to this restaurant and we’ll eat at home.”

And he said, “Well, you’ll have to do the cooking.”

And I said, “That’s all right. I’ll get one big meal a day.”

And he said, “That’s all right.” So I did the cooking for the noon meal. He got up earlier than I did because he was spending a lot of time out on the target range marking targets. And so he would get up before I would and he would get his own breakfast. And then I quite often would be out, I would try to play tennis in the late afternoon over at an Indian Agency, which was four miles away. So I would ride over, play tennis, and then would ride home and always in the dark, of course, probably get home a little before nine o’clock.

It was a typical American family of that period where we were particularly fortunate in that my father was so extremely well educated. And of course as a minister he had constantly improved that education. My mother was extremely well read and like people of that era there was, after all, besides the normal household operations once you finished with, the only amusements left or occupations were either something connected with sewing or something connected with reading. In other words, it was all uplifting.

My mother played the piano; a great many people did at that period. The conversation at the dinner table was always of an uplifting character. We understood politics. We never had any question as to how on earth is the president elected. We knew about the Electoral College. And it was just like the average boy of today knows all about what TV programs are going be on, we knew that. My father always laughed at us for spending so much time reading the sporting pages of the newspaper and being interested in baseball. But the feeling that there was something better to occupy our time. But there was never any objection to that.

As a boy in grammar school in Altadena I played baseball. I did not play baseball in high school. In fact, until I got to Seattle for my last half year of high school I did not engage in any high school athletics other than just whatever games were being played in the noon time. In grammar school, why it was baseball the year round there, before school, recess, during dinner hour.

Groueff: Baseball.

Groves: And after school. Excepting for a short period when they were engaged in track activity and I was not particularly suited for anything in that, that I knew I was too small. I was younger than any of the rest of them.

Groueff: You played tennis?

Groves: I played tennis a great deal. I started playing tennis when I was about eight years of age.

Groueff: With your brothers?

Groves: With my brothers. My mother played tennis a little at that time then gave it up later. And then I played a great deal in California and I played in Montana some and Arizona and Seattle. For the first time I was in high school athletics, I was in tennis there.

Groueff: And you were quite good?

Groves: I was quite good. But a great deal of my time was devoted to riding. I would ride with my father and I would ride alone.

I would say that unlike the modern youth, we spent a lot of time working and there was no wasted effort. We spent our time either working, studying, or reading. We did not do much studying. My oldest brother and I did very well because we did not have to.

Groueff: Were you good in school in your class?

Groves: Yes, I do not think I had particularly high marks but that was not the incentive in those days. The incentive was to finish. And they would not let me skip a grade so that sort of took the zest out of it. I wanted to skip, but they decided I should not or something of the kind.

We went up to Helena, Montana, Fort Harrison, and my father rejoined the 14th Infantry in Christmas of 1911. And just after Christmas he and I went up there alone for I think about four months, and then my mother and sister joined us and then later my brothers came.

In Montana I rode as much as I could except in the wintertime. And even then we went riding every Saturday because my father said the horses needed exercise. And that was torture but did not make any difference; they just had to be exercised. And the roads would be icy; the horses would slip and slide. Most the time you were at a walk and we would normally ride eight miles and bring them in. Their shoes would be all muddy from mud kicked up, because no matter how icy it was there would always be mud somewhere. And then I would get home, and fortunately for me at that period the horses were kept in a common stable so I could not take care of them, which my father regretted. And then I would come home and would wash his leggings and shoes, and my own and my hands would just be swollen from the cold. That did not make any difference; that is what you were supposed to do. And I did not enjoy riding then, but as soon as the weather got better, the riding in Montana was very fun.

And then after a year we moved to Seattle to Fort Lawton, the Regiment moved. To show you the type of the way that we were brought up, when we moved anywhere we went to school the day before the time we left. And we started school, we entered school the day after we got there. So we had just the travel time plus the day of departure and the day of arrival. When we got to Seattle, my father was very much annoyed because their term was ending in a week and they told me to come back in a week. He said he never heard of such a waste of time. [Laughter]

So then when I entered there I decided I would—I said, “Why should I go to high school when I can go to the university just as well” So I finished up my year and a half of high school in one semester plus the summer. I studied by myself in the summer. I took I think five courses and did one outside during the semester, and at the end of the summer I took the examinations in what I had had to do to make up. And I remember one of those was in Civics and Government. And I can remember reading it over and saying, “How on earth do you have to—should anybody have to study this?” Well, of course I knew it all.

And that is the type of upbringing I had, you see, things of that kind I knew completely. I could have taken an examination that was much more severe on government than they gave.

Groueff: Where did you learn it, reading newspapers?

Groves: Reading and conversation.

Groueff: Conversation.

Groves: And my uncle had been a private secretary and a close friend of former vice president—of a man who was later vice president. Well, you just knew it, that’s all, like lots of other things.

Groueff: Did you read some magazines like the Saturday Evening Post?

Groves: Oh we read everything that we could put our hands on. And if it was fiction, we read very fast. It was something non-fiction we did not read as fast.

Groueff: What kind of books? Do you remember some of the books that impressed you or you liked as a child?

Groves: No, none that were particularly well known, excepting I read the ones that my father did not approve of, like the [Horatio] Alger books and the [inaudible] books and all of those any time I could get my hands on them, because I could get them and I would read it in about two hours. The Frank Merrill books, which were the kinds of books that were written for boys of that era. I also read a great, which he did approve of, a great many biographies, the types that were written in those days, such as Garfield, “From canal boy to president,” or something like that. That was the general idea. And I read everything that I could lay my hands on in the way of these simpler biographies before the writers started into explaining there all the queries and quirks that never existed except in the writer’s mind. I think I read Grant’s memoirs, that type of thing, possibly a simplified edition of it.

Of course we all knew American history in those days. We knew geography and arithmetic. There was no hesitation about knowing such things.

One thing I studied that summer that always amused me, I said, “Well, I will take a year of Spanish.” And so I took the Spanish and studied it by myself.

My brother helped me a little. He did not know any Spanish but he was a deep student of Latin and Greek and he said, “Well, I can read it ‘cause it’s so much like Latin.” So he helped me a little bit, not too much. Well, I took the examination and when I got through I think I had about a ninety-seven or something like that for the examination.

And then the inspector, who was a high school teacher, he said, “How are you on your pronunciation?”

I said, “Well, I’m not so good on that.”

He said, “Well, read a sentence.”

So I read a sentence.

He says, “No, you’re not.” [Laughter] But he said, “I think you’re all right. You’ve got the fundamentals here and you can get the pronunciation later.”

The next time I studied Spanish was on the boat going to Nicaragua in 1929. We were on the water eight days and by the time we got there I knew Spanish. I could not speak it.

Groueff: Yes, but you could understand.

Groves: I could write it. And I was in the condition to start understanding it as soon as I got my ear used to it.

So I went to the University [of Washington] that fall. My father said, “I can’t afford to send you to college. You’ve got to stay in high school.” He said I’ve “got two brothers, one of ‘em has just finished and one of ‘em is finished his first year, “And I can’t afford to send you to college.” He wanted me to go to Hamilton.

I said, “Well, Father, I’ll go to the university.” I said, “It won’t cost anything more than going to high school.” Same streetcar fare each way and the same amount of money for lunch, which I think, was probably fifteen or twenty cents. There was never any extravagance.

Groueff: In your family.

Groves: No. My father just did not have the money. And why, we would have a maid, this was customary in those days. But there was never any waste. Having been brought up in a farm where there was no waste. And he also, in his boyhood, his later boyhood, they had the Panic of 18—was it ’73, I think ’73, which was the post-Civil War panic.

See, right after the Civil War there is this tremendous demand for food and everything else. And the farmers were just rolling. And then the Depression came on and they could not get a cent for anything that they sold. My father told me that during that period, the only money that he ever saw paid out was wages to the hired men, which were very small and an occasional pound of tea or coffee for his mother and occasional spool of thread. He said, “We went back from eating brown sugar, which was what they always used, they did not have refined sugar, you see, in those days, to eating maple syrup sugar, which we made.” And my grandfather was a great mechanic. He was a skilled carpenter. He was a skilled blacksmith, a skilled horseshoer.