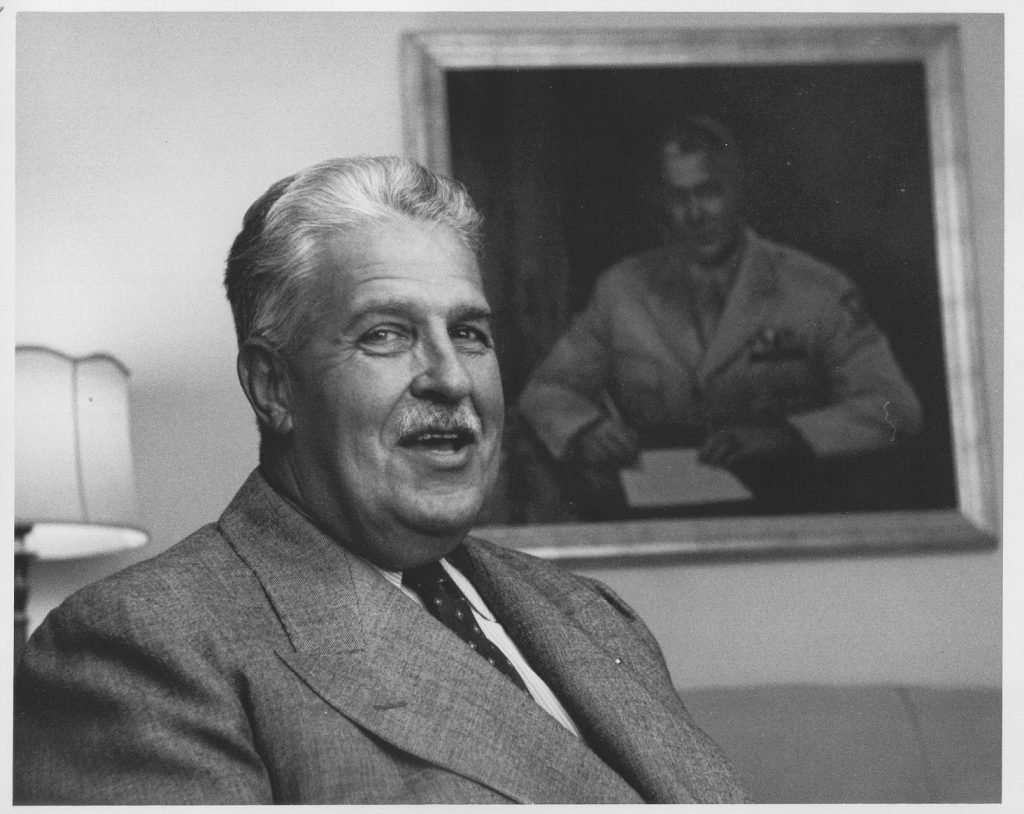

[We would like to thank Robert S. Norris, author of the definitive biography of General Leslie R. Groves, Racing for the Bomb: General Leslie R. Groves, the Manhattan Project’s Indispensable Man, for taking the time to read over these transcripts for misspellings and other errors.]

General Leslie R. Groves: I had seen Dr. Urey in the S-1 committee meeting, I believe. I’d have to check this with the diary. I went up to Colombia [University] to see the work in the laboratories to find out just how far along they were and also to get an idea of where we were going, and was there much hope, and just how much hope in the gas-diffusion process.

I was not particularly impressed with Urey because he seemed so uncertain in his answers to questions and in his general grasp of the project. Urey was a chemist. Dr. [John] Dunning handled the physics for him. It was obvious that Dr. Dunning and Dr. Urey were at outs. Dunning had no respect for Urey. Urey thought that Dunning, not being a chemist and not being a Nobel Prize winner, he couldn’t amount to much either. There was definite animosity. I think that Urey would not have had any feeling of animosity if Dunning had not been what I term, “a go-getter type.”

Dunning was a great talker. If you asked Dunning a question that could be answered by yes or no, he could give you an answer in five minutes. You’d have to break away to stop the answer. I of course tried to deal entirely with Urey, talking to Dunning in Urey’s presence and all of that.

I soon found that things were not in good shape there from many standpoints. It was a typical academic atmosphere. Urey did not have control of the situation. I don’t think that Dunning made any effort to help Urey get control of the situation. That was the general reaction. The more I saw of Urey, the less I liked the situation. He was not a strong man. He had no administrative ability whatsoever. Not only that but in his own technical field he was jumping hither and yawn. I was distinctly not satisfied.

They promised me at the time when I went through the laboratory that they would have a suitable barrier developed in two weeks time and that there was no question about it, they just had a few more things to do. As you know, the barrier wasn’t developed for at least two years later and always it was two weeks more. There were quite a few other things that were not satisfactory, but I felt that in general, outside of the barrier problem, that the theory was right. We believed the theory. The theory seemed to be right. The theory was exceeded to by the British as well as by the people at Columbia. Then we could design the plant with tremendous number of things.

Of course that didn’t mean that we knew everything. We didn’t know anything. But it was a feasible thing to do. Later, it developed that [Percival] Keith could not get any information out of Urey and Urey’s organization, the information that he needed. So Keith had to do a great deal of really the basic research under his own.

Stephane Groueff: But why? Was that from jealousy?

Groves: No. It was inability of Urey to organize his laboratory and the animosity of Dunning and the contempt that Dunning had for Urey. This quarrel got very pronounced and [George] Pegram, the Dean of Science at Columbia, sided with Urey on the grounds, I think, that he had to support constituted authority. But, Pegram, in my opinion, should have come to Bush, under whose direction it really was at that time to tell him that there’s an impossible situation and what did he think should be done, and do something. You couldn’t have the two men there operating as they were.

Eventually, after Union Carbide was selected as the operator, and discussing the problem with them, we solved it by placing at Columbia as I think it’s an associate director of the laboratory, a Dr. Lauchlin Currie who was a director of research of one the subsidiaries of Union Carbide.

His instructions were very definite: he was to be a subordinate of Dr. Urey’s, but he was to make that laboratory a success. He took over in a very gracious manner. He was a Southerner, charming manner. He gave the push that was needed.

Groueff: He kept trying.

Groves: He kept the whole thing. Urey gradually dropped out of the picture where he wasn’t doing too much. Also, we moved the laboratory away from Columbia eventually and got it into a separate building where there was nothing. You were away from the academic area. The thing started, and they went on. We also saw to it that the men who had various departments, like Sir Hugh Taylor of Princeton, had one of the areas to take care of. Professor [Edward] Mack from Ohio State also got his.

Groueff: Sort of decentralized the whole operation.

General Groves: Yes, we got it away so that Currie was dealing with these subordinate sections. Currie, as I say, was a very smooth operator, very competent, skillful, and extremely able scientist.

Groueff: So he didn’t hurt Urey’s feelings?

Groves: No, he hurt them to the minimum degree possible. We tried to get Urey interested in other things. We sent him to England on a trip to look at certain things over there hoping to see what they were doing, but essentially to get Urey away. Instead of staying and making a careful study of it, he just made a Cook’s tour affair and was back in a relatively short time less than a week, I think. He was extremely nervous. He was so nervous that in talking to him at lunch one day, he was unable to take glass of water to his mouth with one hand. He had to prop both elbows on the table, place the right hand with his left hand on his wrist and then raise the glass to and it was still shaking.

Groueff: From emotions? Was he was an emotional man?

Groves: He was completely worried. For the first time, I think that he was the one who showed the most, but the scientists were in this position. Before that project, none of them had ever had to produce. Nothing important had ever been placed on their shoulders. They did research; if it didn’t turn out well, why nobody cared. They may have gotten $1,000 from somebody to investigate something, and their investigation showed that they couldn’t do it. If they didn’t feel like working; they weren’t creative that day, why, that’s all right. They went out and went fishing or played golf or sat around and talked. There was none of this pressure. There was none of the feeling that “The country depends on me.” There was none of the feeling that, “They’re spending hundreds of millions of dollars on this, and I can’t get the answer today,” and start to shake.

Well, we sent him out later to British Columbia, where we had the plant at Trail, heavy-water plant. It was very carefully arranged that Urey would be taken on a fishing trip and would spend at least a week there.

Groueff: To recover his nerves.

Groves: To get rested and so on and so forth. Urey was born and raised in Montana. So the West was not—and I thought that it would bring him around, but no. He only stayed about twenty-four hours, and then he was just so keyed up that he couldn’t stay.

Groueff: You couldn’t get rid him.

Groves: You couldn’t calm him down; you couldn’t get rid of him. And so, we got rid of him by just generally putting Currie in there, ignoring Urey and all of the rest.

Groueff: Was he curious?

Groves: No. He was scared to death of me. If I looked at him, he’d start to quail.

Groueff: Really?

Groves: Primarily because he knew that I expected results, and he wasn’t able to give results.

Groueff: He was the type of giving you an argument and shouting?

Groves: No. He would talk about me. After the war for example, he would make speeches attacking me. I would appear and immediately he would bow and scrape, and you’d of thought that I was the greatest man on earth, although, just five minutes before he was telling what a terrible fellow I was.

Groueff: It is true that he wrote to the President or to Bush [saying] that this project is—

Groves: He wrote to me, and he recommended that we abandon the gaseous diffusion on the ground that it could not be done. This was after we’d spent maybe a couple of hundred million on construction and research. We had this tremendous structure put in there, which was well along towards completion.

Groueff: The Decatur thing.

Groves: Oh, no. Not Decatur. Down at Oak Ridge.

Groueff: Oak Ridge. And he wanted to abandon, and he said that it’s a folly.

Groves: You can’t do it. He wanted me on one occasion to go on the air, get a national hookup over the radio, and to announce to the American people the danger of the Germans dropping an atomic bomb on the United States.

Groueff: That was before your bomb?

Groves: Oh, yes. This was during the war.

Groueff: When the whole thing was so secret?

Groves: Yes. He also was scared to death that the Germans would use radioactive material against us on our landing. Well, that was a reasonable thing. We took that out of his hands when he first suggested something about that, and had that studied by Arthur Compton. And then on the basis of that, we took the action that is described in my book.

Groueff: But didn’t he demoralize the other scientists because, after all, he’s a Nobel Prize winner with authority.

Groves: He only demoralized them there by his incompetent management. He didn’t demoralize the rest because the rest didn’t have any respect for him.

Groueff: Not by the pessimism.

Groves: No. Of course, it had its effect because it induced these people to say, “Why Urey, the man in charge of it, says that it won’t work.” On that basis Lawrence tried to get me to expand greatly the electromagnetics, which would not have been wise. He used that as his big argument.

Groueff: Dunning, on the contrary, was enthusiastic at the time and not—

Groves: Oh, yes. He was a great optimist. He was such a great optimist that you couldn’t believe what he said.

Groueff: So there were the two extremes?

Groves: There were the two extremes. I lost the paper that I want to take with me.