[At top is the edited version of the interview published by S. L. Sanger in Working on the Bomb: An Oral History of WWII Hanford, Portland State University, 1995.

For the full transcript that matches the audio of the interview, please scroll down.]

Book version:

Yes, I am “Marse George” in the poem. There’s some mythology connected with all that business with the tubes. As I pictured the situation, Du Pont was under contract to design and build this equipment following the basic data provided by the group in Chicago. So therefore when the group at Chicago gave us what to us was official data we simply had to follow it. Now it happened several times during the design and construction of this place that they recalculated things, see, this was all very new, new physics. They were breaking ground all the time. They recalculated the situation a few times for certain design changes. Well, we proceeded to make them. Then, finally, as time was going, for one reason or another, Du Pont felt we should put a stop to this if possible, and the chief engineer, Slim Read, said he wasn’t going to accept any more changes.

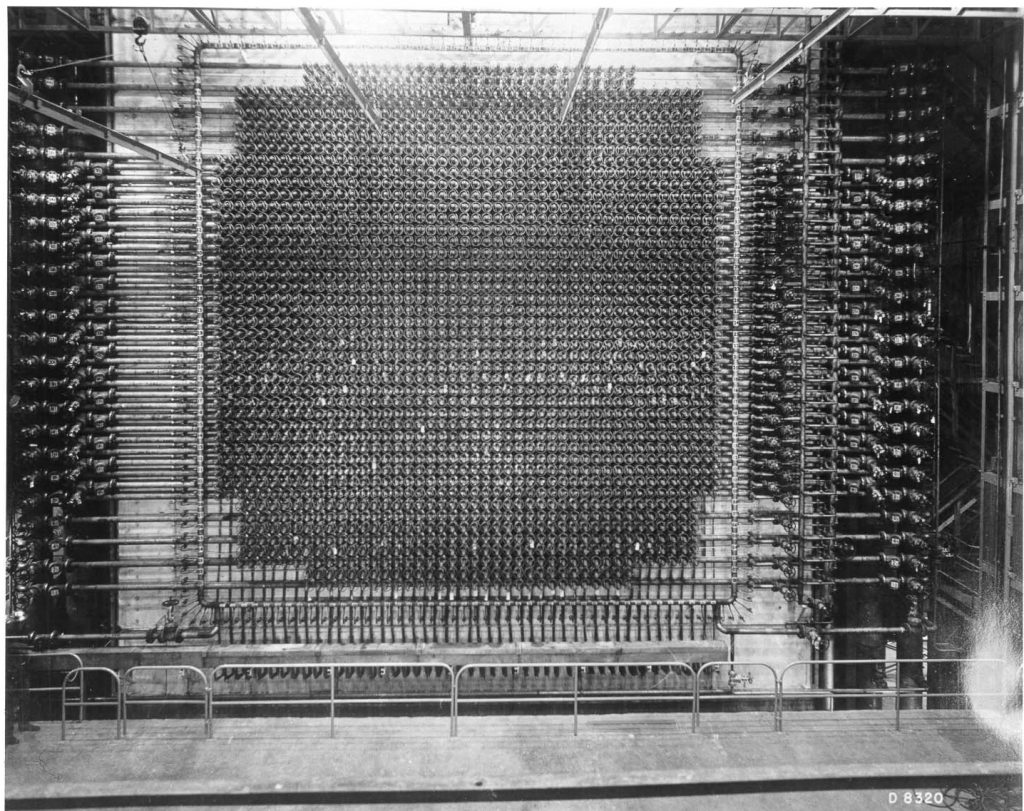

Of course, that is a position you can take but you can’t hold it. So when the Chicago people came through with another change, we had to make it, even though we said we would not make any more. And that is exactly what happened, they came through with another change, and unless we had made it we had every reason to suppose the plant wouldn’t work. That was the change to add some extra tubes. It seems the plant was designed to have a certain driving power in terms of the capacity of the plant to permit the fission reaction. If anything were to happen so that the capacity were diminished, then of course the plant wouldn’t run. We had decided that we keep a 10 per cent safety factor on this driving power, 10 percent excess “k” if you want the jargon.

We made the change Chicago specified, but we insisted there still be a 10 percent excess “k” as a safety factor, and that’s what saved the day, because to and behold when they tried to operate the place some unexpected things happened and unless we had had this excess it wouldn’t have run. We were glad we had the excess, and the excess was provided in the design by changing certain dimensions and setting the number of tubes of canned uranium in the pile. The net of it was that more tubes were made available than the design called for, to the extent of 10 percent, and that let us operate even in the face of this unexpected phenomenon that occurred on the startup. After that, about the end of ’44 or early ’45, the technical group I was part of was disbanded. My contact with the Manhattan District was terminated I guess even before the Hiroshima job.

Full Version:

S. L. Sanger: Hello, George Graves?

Graves: Yes.

Sanger: My name is Steve Sanger. I’m calling from Seattle. You were the same man that worked for DuPont, right?

Graves: Yes.

Sanger: I have been in touch with Walt Simon.

Graves: Yes.

Sanger: I and another man are trying to write a book about the Hanford Engineer Works during World War II. Do you have a couple of minutes?

Graves: Yes.

Sanger: What I’m calling you about is to get a little information from you about some of the DuPont connections. I had a long talk with Dale Babcock in Wilmington earlier. He was talking about the fuel tubes. It’s true, isn’t it, that you were the person who made the decision to add the tubes?

Graves: Well, in a way.

Sanger: You were given credit for that, weren’t you?

Graves: Well, there’s some mythology connected to all of that.

Sanger: Yeah. Do you mind telling me what did happen, as you recall it?

Graves: Yes. As I picture the situation, DuPont was under contract to build this design and to build it with the equipment following the basic data provided by the group in Chicago, under Arthur Compton. So therefore, when the group in Chicago gave us official data, we said that we had to follow that. It happened several times during the design and construction.

This was all very new, and we were breaking ground all the time. They recalculated the situation a few times and called for certain design changes. We proceeded to make them. Finally, the time was going and for one reason or another DuPont felt that we’d better put a stop to this if possible. The chief engineer said that he wasn’t going to accept anymore changes.

Sanger: Who was that?

Graves: Slim Read. Of course, that’s a position that you can take, but you can’t hold it. So when the Chicago people came through with another change, we just had to make it, that’s all. Even though we said that we weren’t going to make anymore. That’s what happened. They came through with another change. Unless we made it, we had every reason to suppose that the plant wouldn’t work.

Sanger: That’s an extra change, to add extra tubes, you mean?

Graves: Yes. The plant was designed to have a certain driving power in terms of the capacity of the plant to permit efficient reaction. If anything were to happen, if that capacity were diminished, then of course the plant wouldn’t run. I was the assistant, and this is a decision that [Crawford] Greenewalt and his technical group took, rather than we keep a ten percent safety factor on this driving power. It was called a ten percent excess k. We made the change that Chicago specified, though we insisted that there still be a ten percent excess k as a safety factor.

That’s what finally saved the day, because lo and behold when they tried to operate the thing, some unexpected things happened. And unless we had had this excess it wouldn’t have run. The excess was divided in the drawing by changing certain dimensions and getting the number of tubes of canned uranium that ran the pile. More tubes were made available than the design called for, to the extent of ten percent. And that was what was left to operate, even in the face of this unexpected phenomenon that occurred on the startup.

Sanger: So DuPont was interested in adding more tubes than the designers had asked for?

Graves: DuPont decided to add the tubes in order to provide a safety factor over the final design that we got from Chicago.

Sanger: Okay. Was any one person responsible for that decision to add the ten percent?

Graves: Greenewalt and I were together on that. We agreed early in the game that we’d maintain this excess. This is a safety factor against misadventure.

Sanger: You were Greenewalt’s assistant?

Graves: That’s right.

Sanger: Was that the title?

Graves: Yeah, I was the assistant technical director.

Sanger: You also worked a lot with John Wheeler?

Graves: Oh yes, John Wheeler was in the group. We had a fairly small group stationed in Wilmington to shuttle between and among the other site. Wheeler was a part of that. He was added as a physicist, which we didn’t have at DuPont.

Sanger: I saw him on my recent trip. He’s in Austin, Texas now.

Graves: Yes.

Sanger: He seems happy there. Do you live in Port Charlotte?

Graves: That’s right.

Sanger: Did you ever visit Hanford after the reactors were built?

Graves: I don’t understand your question. The technical group, which Greenewalt was head of, was disbanded soon after the pile started up. And so my district work was terminated even before the Hiroshima job.

Sanger: Oh, was it? Do you remember when you stopped working for the Manhattan Project?

Graves: Gosh, I don’t remember dates very well. I think it was ’42 when I went in, and I think I was there five years. What was the date of Hiroshima?

Sanger: It was August, ’45.

Graves: Well, you better not take my word for any dates.

Sanger: That’s alright. Mainly I was interested in your work with the design. [Dale] Babcock also mentioned that another suggestion that you had made was that they should make sure that the water was of a certain standard. So you suggested they use locomotive engines to heat the water, etcetera, to test it for corrosion. Do you recall that?

Graves: Yes.

Sanger: He went into that in some detail, so it’s not necessary for you to repeat it. He just said they did find a gelatinous film inside the tubes, which was corrected before the reactors were finished.

Graves: Yes.

Sanger: That’s the way it was, I guess.

Graves: Well one of the things that I was supposed to do on this job was to see if something wasn’t overlooked. As a kind of a sweeper, I wondered about this corrosion with the Columbia River water. So I asked the chief of DuPont’s metallurgical work, a fellow named Maxwell, how you could test for this. And he said the only way you can test is to set it up and run it.

We got a fellow named Cal Kidder to transfer from engineering to us, and he designed and had constructed a pilot plant out of Hanford, which had some of the actual tubes and actual slugs and actual Columbia River water; we set up just to run that thing as long as we could to see if we found any corrosion.

What happened was the slugs in the tube just suddenly began to chatter. The construction was that these cylindrical slugs were held on two ribs in a cylindrical tube. The flow of the water, for some reason or other, made them bounce up and down. They couldn’t operate that way with the noise. So all they did was to put a third rib in to keep them from jumping up. That solved that problem. But we didn’t find any corrosion problem, we found this chattering instead.

Sanger: Yeah. How old are you now?

Graves: Eighty-seven.

Sanger: During the Hanford design period, you did your work in Wilmington, I suppose?

Graves: I was always at Wilmington. I never was located at any of the other sites.

Sanger: Okay. Do you keep in touch at all? Do you ever talk to Lom Squires.

Graves: No, I haven’t talked to Lom since 1960 when I quit, I guess.

Sanger: I see. He lives in Naples, Florida. I haven’t been in touch with him.

Graves: I don’t know whether he’s still there or not.

Sanger: I think he is. I haven’t talked to him. I’ve written him a letter. DuPont got in touch with him for me.

Graves: If you talk to him, give him my greetings.

Sanger: Okay. One of the things that I’ve asked the people who had important jobs on this is what were your feelings after the bomb was used? Are you in favor of it still or what?

Graves: I thought that it probably ended the war and saved the lives of a lot of our people, including my future son-in-law.

Sanger: Is that right? He was in the Pacific?

Graves: He was in the Air Force and getting ready to invade Japan.

Sanger: A lot of people mentioned that. They knew people whose lives were probably saved by the bomb.

Graves: Well I think that was the justification. That was the good part of it. I think Truman took that position didn’t he?

Sanger: Yes. Okay, I was mainly interested in your perspective on that.

Graves: I want to comment on that last point. It’s always struck me that we would have had World War III long, long ago if it hadn’t been for the bomb we held over the Russians heads.

Sanger: Yeah, I think that’s right. Well, thanks a lot for talking with us. This is the sort of thing that I was after.