Stephane Groueff: Mr. Hobbs, part two. So to go now to how you were contacted for the Manhattan Project.

J.C. Hobbs: You see, [Ludwig] Skog was one in the group and had me in on –

Groueff: And [William Francis] Gibbs.

Hobbs: I had a chance to sit in meetings with him probably half a dozen times. That is really the first time I had any personal contact. He had come to the plant, but that was E.G. Bailey, the Vice President of Commonwealth Edison Company, was my old friend. We had worked together since 1911.

I felt that I owed it to the utility company. Which really, I was giving it to the people of the country. When I give a new invention to the public utility, it is because they use it and the public gets the benefit. Some of the politicians are getting kind of rambunctious; they are not giving the utilities credit for having, for instance, saved four and a half pounds out of five pounds of coal per kilowatt-hour. And they are going to have an investigation and rate cutting because they think they are making too much money. Actually, they are limited in their amount, and it comes back to accounting and bookkeeping as to whether it is a replaceable value or whether it is a depreciating value.

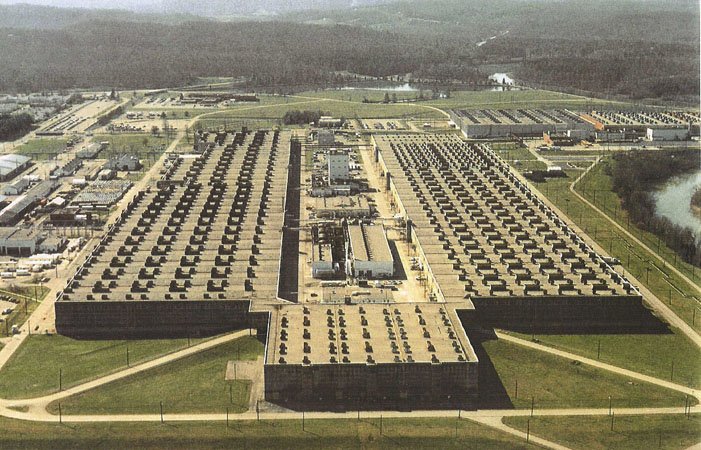

Then Skog stopped by New York on his way from Oak Ridge after he had been down there on this electric plant to have a talk with [Albert] Baker and report on things rather than write a lot of letters, which were taboo in those days anyway. I think I wrote two or three letters in two years.

Groueff: Really. At Oak Ridge?

Hobbs: Oak Ridge.

Groueff: Only two or three letters?

Hobbs: Yeah. You see, that was super-secret. They told me when I went in, because I would not go in unless I knew what kind of a product and what it was. They told me in the first conversation, “When this plant goes into operation, the war ends.” So that meant they had a lot of confidence and that is what actually happened. It did not win the war, but it made a good punctuation mark, a period, and it saved a whale of a lot of American lives.

Groueff: Oh yes, absolutely.

Hobbs: And billions of dollars in costs, because it cost $100,000,000 a day I think to run the darn war. Anyway, so he stopped by and – I am sorry, most of my records are north. We had a main office up there. That is the old headquarters. And I have a letter, which Baker wrote to the government in February ’43 and outlined a situation at the time they brought me in. The reason of this letter is that because I had come from an active company as a top man and had high income, why, even on a half-rate pay. You see, I would not give up my Navy work. I said, “I will help you, but only on a half-time basis.” So I agreed to –

Groueff: So you continued with the Navy, but not with the other company.

Hobbs: Oh, the other company I had already quit. They wanted to compromise with some racketeer labor.

Groueff: I see.

Hobbs: I had good advice from an old, old friend of mine, formerly with the boiler company, but at that time head of a company, which was a small company. Their annual income was something over a billion dollars. And this fellow was in charge of 65 manufacturing plants all over the world. I knew his employment experience, which I can narrate at great interest. So I called him in connection with our situation, and he gave me the picture and exactly what I was doing.

But we had some lawyers on our Board and had an advisor, just like this consultant in New York. This consultant from Cleveland, legal consultant, said to me over the phone, “I am not sure your advice is good.” Here was a lawyer that sits in an office and does not know anything about labor. Socialite lawyer – but money and a big name and so on – telling me that the advice of a man who runs 65 factories, big ones, all over the world, was not good.

What did I do? If the directors do not want me. Again, when I went out, the President said to me, “I wish I was going with you.” You know, that type of thing. You cannot get results if you do not have cooperation. If you have cooperation, fine.

Well, when he talked with Baker – I have to be careful now just what I say. To make a long story short, Baker told him they were in real trouble. And they wanted somebody to correlate a program to solve a lot of problems, which they had not been able to solve. They had been working on it a long time, but they would get up against a roadblock here and a roadblock there. And the theorists were losing confidence because they could see that certain things would prevent it from working at all.

Well, they also, in this letter, said that they had determined before they hired me to find a man who had experience – who was qualified, I think, is the word they used – to build big new things and so on and make them work. Skog, a former associate of Baker’s, gets on the telephone and he calls me in Ohio. I happened to be at home that day, and he says, “J.C., I wish you would come down to New York. I need you.” He could not tell me what it was for, and nobody had ever heard of the Manhattan Project. When I got down there, they told me that I was only one of seven. I think they were pretty stingy with their figures, but only one of seven who knew the whole story.

Groueff: But he called you on the telephone and you accepted to go.

Hobbs: No. All I told him was I would go down and talk with him. So I went down, had a conference, and, of course, I was not cleared for that project yet. So they could not tell me very much.

Groueff: Who did you meet?

Hobbs: Baker.

Groueff: Baker.

Hobbs: Baker and [Percival] Keith, and Baker’s brother-in-law, [Ronald B.] Smith.

Groueff: That was in the Woolworth Building?

Hobbs: That is right. Woolworth Building. Fifth floor, I think it was. Keith’s office was over in a corner, and Baker was back a little ways. When they finally got me to agree on a half-time, they gave me an office next to Baker’s.

Groueff: Who greeted you? Keith and Baker?

Hobbs: Keith and Baker. Yeah.

Groueff: They told you the whole story.

Hobbs: That is right. And they did not tell me the whole story the first time.

Groueff: They told you the story about the diffusion and all.

Hobbs: No, they did not tell me a thing about diffusion or they did not tell me –

Groueff: They talked about technical problems and –

Hobbs: All they said was, “When this plant goes into operation, the war will end.” That was all they had given me at first. Then they started security checks, and I had been checked so doggone many times that they did not have to go very far, I guess, because-

Groueff: There were [inaudible].

Hobbs: And a couple of times. I mean I am on manufacturing. I was building a magnesium plant and that is for government service, and chlorine and all those things. Well, anyway, they gave me a lot of papers, filled out who my grandmother was and all this and that. So I filled those out.

Groueff: But you accepted the –

Hobbs: No, I did not accept it.

Groueff: But your first reaction was favorable?

Hobbs: Oh, my first reaction was that the country needed help. And with Skog, with his past, I knew he was a conservative, with his past. I did not know Baker. I took his word, and as I could not see anything like I could in some of these other plants.

Groueff: You smelled that it was something very big and very important. It was not just one of those –

Hobbs: Well, when they told me, that is why I believed them. So I filled out the papers, took them back. One of them – I would not fill it. I told them I would not work for them if that was insisted. That was this sneaky patent assignment, which anybody that works for a corporation, if he does not have the power to resist it, has to assign all his inventions. Of course, they asked me to as a routine, just a routine employment.

Groueff: To give away your inventions?

Hobbs: Yes. There was no distinction made between past and present and future. Here I was doing work not only for the Navy, but I had my own invention program. I already had 25 or 30 patents.

Groueff: Already?

Hobbs: Already. When I went back, why, they had already decided to hire me after the first conference. I gave Smith, who was Assistant General Manager, the papers and said, “This one I cannot. I cannot work for you if you are going to insist on that.”

He did not hesitate at all. He says, “Okay, we want you.” So that was that.

Groueff: So you kept your patents?

Hobbs: All my present – my patents, my inventions, are my tools in trade. Also, the patents that I had before I went down there have since yielded me too much.

Groueff: A lot of money.

Hobbs: Yeah. No use for it. So I was going in on a temporary basis. Now, I think –

Groueff: They could not wait.

Hobbs: I could not bust up my own thing, and I also had to be free to take care of the Navy. And I had to be free to take care of my other clients. So they took me on that basis and –

Groueff: When did you start?

Hobbs: September 8.

Groueff: September 8, ’43.

Hobbs: ’43.

Groueff: Did you work in New York or in Oak Ridge?

Hobbs: I was in Oak Ridge only three times in the whole time.

Groueff: Really? You did not work there?

Hobbs: No. I had an office right there in Manhattan –

Groueff: In Woolworth. You moved your family to New York?

Hobbs: Oh no. I was not in New York. You see, I only had a half-time job down there. I was not going to – I had a lot of other operations and –

Groueff: Where did you live in New York?

Hobbs: As usual, I stayed at the Commodore Hotel, but only for one day. One of the men there had a room at the Downtown Athletic Club and he was moving out.

Groueff: Oh yeah, Athletic Club, yeah.

Hobbs: The Downtown Athletic Club. You know where that is?

Groueff: Yeah.

Hobbs: He was moving out because his wife was coming to town. They were taking an apartment uptown somewhere. So we fixed that up. I took over the 30th floor corner room, southwest corner, which was higher than the Statue of Liberty torch. I could see over the whole thing. In other words, it is up above the dirt line too.

Groueff: So you lived like a bachelor there. The days –

Hobbs: Yeah, well, I would go to New York, and would not have to stand in line for hours and hours to get a room. I set up an office there because the Navy office was right next door. Gibbs & Cox had several thousand engineers working in 21 West, and this was 19 West Street.

Groueff: How did you work the two jobs? They were full time jobs each, no?

Hobbs: Oh no. Half time.

Groueff: Yeah, but it took a lot of time for you, no? And energy and mental worry.

Hobbs: Well, I tell you. When I got through, I was so weak after a little over two years on that. I had trouble lifting my suitcase from one step to the other out of the subway to catch my train west. Because I was really working night and day then.

Groueff: You are not the kind of inventor who works just the idea. The brilliant ideas come now and then and in the meantime. You are a very steady worker for hours and hours every day.

Hobbs: Well, I do not know how to answer that question, because a friend of mine in New York, he was with the boiler company at that time. I had made a lot of inventions that he knew of and solved a lot of problems. He says, “You solve these things so fast that people think they are not worth much.” He says, “You ought not to give them the answer immediately.”

In other words, if you have a lot of experience, I can usually look at a problem pretty fast and get an answer. But the big thing is then to overcome all objections, and get the thing into practice without somebody botching it all up with some of the weaknesses and features of the old stuff, which is no good.

Groueff: Did they give you a free hand on the Manhattan Project for that?

Hobbs: I want to tell you a couple of other things about the Manhattan Project. I said, “I can only work half time.” I told them that. And I said “No routine, no administrative at all.”

Groueff: Red tape and –

Hobbs: No, nothing at all. So yeah, that is why I wrote a couple of letters. At least that is all I remember right now. I went down and the very first day, they did not give me any specific instructions of any kind. They just wanted me in the picture. Skog knew what I could do, and he probably told Baker something. I do not know what he told him. Baker never told me. But I did find out what Baker was thinking when he wrote this letter to Washington, because they had to go there to get approval for a half salary for me. I mean, for the amount, my half salary.

I think really I was the highest paid executive – not on the Manhattan Project, because I was only getting half pay – but my half pay was so high that it went over what they were allowed to pay full pay without getting Washington’s approval. But having worked in a big company and having lots of fringe benefits – in other words, when I go into a company, I put my money in the company, too.

Groueff: I see. Yeah.

Hobbs: Some of the stock – I was fortunate. There was a family close-held company, but I had some friends. When some of the executives died or something, and the stock had to be sold to pay taxes, they let me in on it. Some of those things have split as much as twenty to one. That was one of the ways I made money because I would do things. Cut coal consumption 1,000 to 300 and that put more money. They told me frankly that in ’32, if I had not been in the picture, they would have gone bankrupt. Because I was in there in ’24 and I had eight years chance to just cut costs and cut costs. One cost in the main engine room, which is a whale of a big engine room, oil costs dropped from $5,400 to $400 a month. I did not use oil for some things. I used waste soda water for lubrication, which was doing a double job of washing the gases as well. So those are things, but I think if I could go back to basic things, I think every worker ought to be required to invest in his own company so as to have an incentive to do the right thing.

Groueff: Yeah, absolutely.

Hobbs: In the government work, I sat in Washington years later on other projects, and we discussed the idea of doing away with the cost plus and the percentages system and putting it on an incentive contract basis, whereby the contractor would be paid extra if he –

Groueff: Improves the –

Hobbs: On a competitive basis, cuts the total cost below a certain thing. Now when I got into this picture, the very first day, in order to know what the thing was all about. I did not go to Oak Ridge, because that is just a bunch of bulldozers and stuff running around. I asked for a drawing of the whole plant. They had the thing laid out. They were putting foundations in. They were building buildings and doing a lot – I think I better delete some thoughts. But anyway, I would not have done it that way at all. But they were so far along, I had to take a job that was half done and throw out the things that were no good.

So what in the world did I do? I took a yellow pencil, and went over this drawing freehand. Made chicken scratches or something, my man used to say, on drawings. Freehand. Then I hunted up the chief engineer, whom I had never met, and took this drawing in and laid it on his big double desk, which fortunately was clear. He looked at it, and then he looked at me. He said, “The original design looks foolish, doesn’t it?”

Groueff: That was the engineer?

Hobbs: That was the chief engineer of the Manhattan Project there. Chief engineer. That was [Allen] Fruit.

Groueff: Fruit?

Hobbs: Fruit was his name. He is not an aggressive type fellow, but I suppose a good fellow for that type of thing. I do not know. He never failed to cooperate. That one idea, without me knowing anything about the detail of their troubles. You see, I just come in, look the thing over fresh. Did not have any, no briefing at all, of any technical operations.

Groueff: All the cascades and barrier, you did not know at that time anything?

Hobbs: I did not know a darn thing the first few hours. I asked this, and from a purely business mechanical standpoint, I took out two-thirds of miles and miles and miles of piping.

Groueff: Two-thirds.

Hobbs: $20,000,000 worth of piping I took out. Just the first – the head of the Army who was stationed in Kellex offices there –

Groueff: Stowers.

Hobbs: Colonel [James C.] Stowers was asked one time when he first knew I was in the picture. He said when the engineering department went up in the air because I had cancelled six months of their work.

Groueff: That was the first?

Hobbs: That was the first day.

Groueff: The first day.

Hobbs: The first day, yeah. Sometimes I think when they were griping about the half pay, nominal pay, not what my actual earnings were – but I just arbitrarily set a figure that was low enough so that the half pay I thought they would not have any trouble with. I think it was 27 [$27,000], something like that. But anyway, they were griping about that and they kept on griping, and I never got any money for six months! Each day I took each problem and I analyzed it. But they were using conventional construction. What I call the T-square triangle method. They told you how many steps were in this process?

Groueff: Yeah, it is written some thousands, two or three thousand or something like that.

Hobbs: More than that. Anyway –

Groueff: That is written. It is out.

Hobbs: Yeah. That one thing saved a whale amount of money. Saving money on that project had no weight whatever. Any amount of money you wanted to spend could be spent. Yeah, well, I was the one responsible for that plating.

Groueff: The story they told me: the only metal they found would not be corroded by the gas would be nickel, but there was not enough nickel in the world to build the pipes.

Hobbs: That is right. They had priority, too, over the Navy, and the aircraft, and other people. They were actually building the valves out of solid alloys. That was a whale of a big problem. I would not go along with that. When it comes to the pipe, why, even when they got to the plating. It happened that the President of Republic Steel and I were old friends in Pittsburgh, when I was with another steel company. His wife and my wife went to the same college together, and so on. They were expecting to ask Republic to build a special plant to build this pipe. And all I did, my general modus operandi – is that the way you say it?

Groueff: Yeah.

Hobbs: Was to look and listen. I attended staff meetings, and I would listen to all these people. I usually sat back in the corner somewhere at the end of the table and just listened. A lot of the things I heard, I knew were not right, but I did not object because you get into all kinds of discussion, and I was not a doctor. So they shipped stuff over from England that they had experimented with over there and decided was all right. I looked at it, and shook my head and put it down on my desk. A couple of weeks later, I looked at it, and it had gone to pieces as I expected. It was rubber. Some of the things, they would come in one week and say, “It was all right,” and the next week they would come in and say, “Oh, we had trouble.” Well this plant had to be built so it would run at least until the end of the war. It has been running ever since.

Groueff: Yeah, I guess. The first try had to be the right one. You had no time to –

Hobbs: That is right. Well, it is just like me, when I build a boat here and I start it across the Gulf Stream or somewhere else. I cannot have it go to pieces in the middle of the Stream. It is not good. In other words, that is the type of basic training I had, one man responsible for all the operation. When we go out here in the old days, why, we had to be able to come back.

Well, the Republic thing: afterwards, one of the official committeemen – when I was just going around listening. But it so happens when I knew some of these people. I could ask them pointed questions, and they knew my past. They knew I would not be satisfied with anything except the correct one. They were not interested in getting the job particularly. So when I decided with Charlie White that it was not a Republic Steel job.

Because in the first place, the way they were going to make it was going to plate steel and roll it up and weld it. And then spark off the flash and then still leave a little streak of bare iron in there. Which was not good, but they thought they could get along without it, if you can build something without doing that. The main thing was they did not even know what sizes and what lengths of pipe they needed at that time. That was earlier.

So that is not practical. You cannot build a plant to run a half a day to produce all the pipe or whatever it is. Because they have big builds there. And not know what you are going to make. So this fellow said, “I did not know which side of your mouth you were talking out of.” Well, when I found it was not right for him, then this other Bart [Manufacturing Company] thing was the right answer. You have got Bart in the picture, did you?

Groueff: Which one?

Hobbs: Bart. They did the plating job. I went over and inspected that job.

Groueff: That was from New Jersey?

Hobbs: Yeah, right across the river. I also went down to Philadelphia, I guess it was. No, Chesterville. We inspected a piping company down there that was bidding on it. But they did not get it. Speaking of piping, when the Vice President of Midwest Piping, who came into the picture: they were the ones that really put the stuff together. And I was going over changes and details.

This piping, I just passed over a lot of problems, which I did not even know existed at the time I passed over it, but I would have done it anyway. For instance, the piping joints were ones that Baker and Skog had designed in Chicago. This is what they called “Sargol” joints. Instead of Sargent & Lundy, they called it Sargol. Big heavy bolts and flanges, and a flange that came up through, and then they would weld – the edge of the pipe would be flanged out and weld the edge and it would hold it together. It would take millions and millions of those things. And they could never have made it tight. I did not pay attention to that, but as soon as I saw that joint. Did they tell you how tight this piping had to be?

Groueff: Absolutely vacuum, no?

Hobbs: Well, one of the expressions that I think is easy for the ordinary people to understand: if you put a full vacuum on it, the leakage has to be so small that it would take 87 years for the pressure to come back up to atmosphere.

Groueff: 87?

Hobbs: Years.

Groueff: So it was practically impossible at the first site.

Hobbs: All the construction in the beginning.

Groueff: Over millions and millions of pipes.

Hobbs: I know one case where there were six valves ready to ship out of Chicago. They would not pass the test. Fortunately, they had this mass spectrometer test, which was very sensitive. And they would not pass the test. You know where the leakage was? The leakage was going through three feet of solid monel metal. Three feet! It was not actually solid. It was coming through the valve stem.

When you roll a piece of metal, if there is any defect in the original ingot, it is like a piece of glass. You can take a glass tube, and you can heat it and you can pull it forever. If it is a tube to start with, it still has a hole in the center when you get down to even fine hairs. It still has a hole. If you have a defect, what we call a pipe. That is a shrinkage crack in the ingot when you pour it. The ingot is not handled in the right way, and at the right temperature and the bubbles do not have a chance to get out, it leaves that. Well, if you take that ingot and roll it out or draw it out into long rods or tubes or bars, and then use those for valve stems. The leakage through the length of that rod was enough. They were fussing around there, and I happened to be in Chicago that day at the Crane Company and I heard about it. I was not interested in the manufacture of any one thing. I was interested in the whole thing. And I started in and then I went from place to place, looked at the stuff.

I was directed once to go to Chrysler, and look the thing over and write a letter. I dictated a letter there, but I left it to be signed by the official, the man who had the responsibility at Cadillac for handling the Chrysler account. Well, that man, he was going to be there the next day. And he had signed it and given it to Chrysler. He picked it up, and took it back to New York, and put it in these files, because he was antagonistic. He was the only one that was antagonistic to me in the whole crowd that I knew of.

I had asked for some drawings of some of the equipment that he was handling. I never got them, and one of those was valves. So the way I got the information was to go to the place where they are building it. Usually, I went at the same time they were having another group there, so I could listen to the conversation as to what they were planning to do and how they were going to work it out. If I felt that they were not going to come out with a good answer, why, I would make suggestions.

After a couple of suggestions, and being kind of passed off because of the domination of this fellow, then I went straight to Crane on the valves. This fellow, incidentally, was a fellow who was allowed to go back to [Morris Woodruff] Kellogg, and Skog was asked to come in as a nominal administrative head. And eventually he did.

Then on this Crane operation, though, after I listened to two meetings, and I knew they were headed for, you say hell-bent for election – they were headed for failure. They had been working for years, more than a year, both Kellogg and them, and they had not produced one single valve that would meet the specifications. Not a valve.

So what did I do? I was only half time. That week I had been up to Allis-Chalmers [Corporation]. I had just timed it so that I could drop back in there. They had a two day meeting, so I stayed both days. And Friday when they quit, and they had appropriated $40,000 for some tools to make some small valves, the two inch and the four inch, I think it was, or maybe just a four inch. Of the kind that were absolutely no good. I would not use them on low pressure. They were what we call a “plug caulk.”

To make a plug caulk, you have to have two major miracles and an impossibility that does not happen. A plug caulk is a tapered plug valve with a hole drilled through it sitting in a case that has to have exactly the same taper. It has to stay the same taper, even though you have got pipes holding on the end of this that are straining. Then you put it out. And the only reason the plug caulk worked in those days was that they had to have lubricant on it to seal the irregularities of machining. It had to be a perfect surface and no joints, not a millionth of an inch even. It could not be allowed to change.

Well, I knew from experience they can – steam piping and some other piping, that there was expansion and contraction going on in all valves. And that in some places there was as much as a 100-degree difference in temperature between the top of a valve and the bottom of a valve due to the natural tendency of the heat to rise. If you had one thing expanding and contracting, and you were not allowed to use any grease. Did they tell you that grease was fatal?

Groueff: Yeah. No grease.

Hobbs: They used white gloves to put the stuff together and just rubbing your hand over the inside of the pipe –

Groueff: Would make a difference.

Hobbs: It might start [a fire]. I saw laboratory results where the valves had been melted down, actually melted metal. The fire started inside. I was not there to see how much grease was there to start with or how much burned up, but anyway, it was enough. We just could not afford to have anything like that start, because eastern Tennessee might have seceded. Another state. After I listened to that, I went back to my hotel room instead of going home. I was due to go home the middle of the week, but I stayed Thursday and Friday. I went to the hotel room. I started to work and at 7 o’clock, a little after 7 o’clock the next morning –

Groueff: You worked the whole night?

Hobbs: No, I did not work the whole night, because I was able to get the thing sketched out. And then I got a little sleep. The superintendent of the Crane plant was a practical fellow, and he had been very nice. He lived in the north end of Chicago and the plant is down the south end. He would stop by the hotel on his way to the plant. He was an early riser, and he usually came by there between 7:00 and 7:30. So I had to be up and have my breakfast and down on the street ready to ride out with him, which I was glad to do. So as soon as I got in the car, I told him the answer. In the meantime, he had showed me what they were making. He had called their valves “monstrosities.” He was not a technical man. He got a lot of kick out of kidding us who were college graduates.

One time they had a big dinner in Chicago, and one of the atomic engineers and I were at a table, and he was at another table over there, and the speaker, who was a brother of – I guess this fellow was a Nobel Prize winner, too. Was kind of razzing the college people and emphasizing, as I think you were emphasizing. What the dickens was his name now?

This meeting was sponsored by four of the national societies. I was a member of three of them, so I thought I was eligible to go. Anyway, I well remember [Clarence] Larson looking over at our table and giving a big smile when he was razzing the college theorists. But anyway, he had told me some of their problems. I did not have to ask him because I knew that type of valve was no good. They had an eight-inch valve there that weighed a ton and was made out of solid alloy.

Groueff: Eight inch, which is a ton?

Hobbs: I am pretty sure it was close to a ton. It is a great big thing and it took a big crane to handle it and all. I disclosed a brand new invention to him.

Groueff: In the car when you were driving?

Hobbs: Going out. And we went from there directly to the atomic secret building, which was off in a corner of the property away from the other buildings. I had already explained it to him, but he went in with me and we talked to the project manager and one of the draftsmen. I asked the draftsman to take my rough sketch there and put it to scale on a ten inch. I like to work on a ten inch because then if you go up to twelve, you add 20 percent usually, plus some adjustments. Where if you go back to five, you can expect none of – it is easy. You do not have to divide by–

Groueff: By eight or –

Hobbs: Yeah, well, anyway this is Saturday now. The rest of the crowd who was supposed to be responsible for all this thing had gone home. I was still working there on my own time. Back at the time this happened, it was two months after I came in. I did not find out that they did not have valves. The Army started complaining the whole plant was being held up with no valves.

I knew a little bit about valves, because I had been working with big valves and all kinds of special valves since 1911, when I first went to work for the light company. My first job was to find out what was wrong with all the main valves in a plant that had 18 boilers in it. They were all going to pieces. They were all Crane valves, brand new design. And I soon found out, I made tests, and that was in 1911. Over the years when it came to my high-pressure work, I had to design all of those, because none of the valve companies had any valve that was really reliable or good and suitable. So my own –

Groueff: You had a big experience.

Hobbs: Well, that was just an incident to my administrative work. But if one feature keeps you from being successful, what do you do? You fix it, do you not? You get busy, and you put some metal around your idea, and do not put anything else around it that is going to cause trouble. I went into the piping job –

Groueff: So if I understood you correctly, because I am quite a layman, the big problem with the valves were with the heat –

Hobbs: They could not be tightened.

Groueff: They would be extended and –

Hobbs: Well, just everything: heat and the weight.

Groueff: And the motion.

Hobbs: Usually because the valves weighed so darn much, they had built a foundation. One of the reasons that they were holding up the plant down there was because they did not know how much steel to put in to hold up these big valves.

Groueff: I see.

Hobbs: Okay. And then if you put a valve like that on a foundation, then they have a long pipe, some of them that big and later up to 42 inches. You put a thing on a foundation and then you put a long pipe out there, and you have some weight going up and down and vibration, what does it do to this valve?

Groueff: I see. And it had to be perfect.

Hobbs: It had to be perfect to start with, and you cannot make a valve perfect. You cannot build a perfect – because when you are machining it, the tool generates heat.

Groueff: Yes.

Hobbs: When that valve, at the time the tool leaves it, it is in a perfect alignment.

Groueff: It is that sensitive?

Hobbs: Oh, sure. Very sensitive. There is a tile patio floor out there. Of course, it has been in there 25 years. But the heat has expanded and contracted that so that it has broken a lot of the joints. It has got to be rebuilt one of these days.

Groueff: So your invention was how to prevent this or how to take into consideration the expansion.

Hobbs: Yeah. In other words, I recognized expansion and I just would not ever fight it.

Groueff: I see. You did not fight expansion.

Hobbs: I did not fight it. I made the expansion so it could go itself.

Groueff: I see. And you could not find the motion or the pressure or the weight.

Hobbs: No, it did not make any difference with my design.

Groueff: So the design was such that it took into consideration all these elements, friction –

Hobbs: Yeah. Take this job as compared with my previous work, which I had done seven years before on my 2,500 pound [boiler] and 1,000 degrees. You really get expansion. With 1,000 degrees, you get about seven inches expansion in a pipe for each 100 feet of pipe.

Groueff: Seven inches?

Hobbs: Seven inches. That is right. Seven inches. So you are dealing not with something as solid. And you know what the other valve companies, everybody usually does when they get something that breaks? They make it heavier and that makes it worse. They have been doing that on boiler tubes. They have been doing it on all kinds of things. They just make it heavier. And here they had this great big monstrosity, which is the accurate name. George Larsen was a mighty practical Swede. He was the superintendent of the big Crane plant, and Crane was the biggest valve company in the world. Is yet.

Groueff: And they built your valves.

Hobbs: They had a contract. Now listen to this one. They had a contract, a secret contract. Of course, even they were not told what this plant was for. All they had was a contract to furnish certain valves of certain sizes to do certain things. They had worked a long time; Kellogg had worked a long time. Kellex. Nobody had come up with an answer, and they were all headed in the wrong direction. They would never get to the right goal if they were going in the opposite way.

So the thing at Crane was that – and this is the secret of my success in the whole operation. I did not go into the picture until they recognized that they were failing. It was not my fault I did not go in earlier. But if I had been in earlier, there would have been all kinds of opposition. Because of numbers, and because of rank and authority, and all that kind of thing, I would not have been able to do the same kind of thing I did in my own plants where I was the top man.

Groueff: In this case they gave you free hand because –

Hobbs: Well, they were in real trouble. And they wanted help.

Groueff: But did they recognize the value of your contribution? For instance, when you designed the new valve, did anyone have to approve it?

Hobbs: Oh yes. The Kellex people had to approve it.

Groueff: I see. But they immediately saw that it was –

Hobbs: Well, it came through remarkably fast. Now keep this in mind. Crane Company had a firm contract with the Army to deliver these valves They were not responsible to Kellex, except that Kellex did have an inspection feature. They were supposed to inspect it.

Groueff: But Crane accepted your design immediately?

Hobbs: Crane and – let me finish the rest of that story. I made this design. They were quitting work at noon. I wanted to catch a noon train so as to get back to – you see, it is 400 miles or so, and lots of hours between Chicago and Ohio: Painesville, Cleveland. So this draftsman, of course, was not fast enough to design a whole valve in three or four hours. So all I asked him to do was to design certain features of it, which were the key features. That is the heart of the thing. The heart of the thing, I would say now, is that you did not allow any surface to slide on any other surface because that would scratch it. And the scratches would be fatal. I knew that I could build a valve that would have a round tubular seat not attached to the body here, but way down here. So that this part could wiggle and do anything it wanted to, and this still would fit the valve itself.

Groueff: This tube is made also of a metal.

Hobbs: Oh yes, this tube is a part of the valve, but it is attached at a remote distance from the valve. Then the valve itself was a symmetrical piece of metal which would not distort when temperatures were different, and it was thin enough so if the temperatures would go. It was pivoted in the middle, so it could wiggle any way that it wanted to.

The secret of this is that this valve was close together down here and then it came out against the seat and it closed. No sliding, no movement of any kind. This plug valve was all sliding. All the other valves were sliding. I could have built a valve that would be just one seat and we would have the gas come up here, we will say, and then come here and go out sideways. Then I would have had one seat that I could have made go up and down. That is what we call an angle valve. But that would have put a lot of friction in the piping system and besides, it is a big, awkward thing. If you have a pipe going along here and want to put a valve in, then you have to go along and put an elbow through there – I mean a valve there – and then an elbow here to get back into line again.

Every time you had a joint, you had a hazard, a chance of a leakage. These all had to be tested, every one of them. In order to test this system, you had to have pipe valves to start with. The valves leaked and you got a leakage in the system, even on the short section, you would not know where your leaks were. Anyway, when you make this unit, where it came down. It was guided, it could not go out until it got right in line, and then it went out on a couple of tracks right into this. Well, I asked these fellows just as soon as they quit work to make a print of what they had done in the way of this layout and send it to me in Ohio special delivery so I would get it Sunday morning.

Sunday morning I got the letter. I got a long letter saying it would not work. So I sat down. In other words, they had not understood the thing. Even the most expert valve people in the world still had not understood. But I was not surprised. You know why? Seven years before, when I asked them to bid on valves for my plant, I gave them a detailed drawing to scale of exactly what I wanted. They sent the head of their Research Department over for a conference. I would not deal with a salesman because I knew that they did not know the technical things that I had to know. I would not buy them. They sent these fellows over, and I had asked them to bid on a kind of a valve that they would offer for the service that I needed. And they come in with the stuff that I knew all about beforehand. I knew it would not work. Then after each one of them – I asked different companies to come in. Then I would hand them a drawing that was colored, each part colored, so they could understand it easily. I am going over the country for my colored drawings, you see.

Groueff: You make your drawings in color?

Hobbs: Well, after they are colored, I would take a crayon and I have a way. I will show you some of those later. I think you would be interested in the practical aspect of that. This fellow that came over, he did not warm up at all. I saw the correspondence file later when he went back to Chicago, and I was just crazy, that is all. They lost my business, of course. Before the war was over, Skog told Crane – now we are getting ready to build some new power stations, and when we build those stations, we want some good valves. And Skog says, “I know the fellow that can do it.”

Of course, in the meantime, I had revolutionized the atomic valve thing. And Skog told him. Of course, he knew about the valves that he had seen when he came to my plant seven years before. So he gets the Vice President of Crane, President of Crane and I together. Of course, I had been together with him for six or eight months to revolutionize the other thing, so they did not need an introduction. But it was – in other words, six years after I disclosed an invention to them that revolutionized the valve industry of the world. There has been probably $50,000,000 or $75,000,000 worth of those valves sold.

Groueff: But at that time, they were secret during the war.

Hobbs: No, my valves.

Groueff: Oh, yours.

Hobbs: My valves, the high pressure. But it took them seven years to get away from their old habits and the tenacity. They had probably gone out to customers and told them no good. Of course, not too many customers knew about these valves. I had used them, and I told some of my friends about it and they knew about it, like Skog. But within a very short time, every valve that Crane sold for the pressures that they were designed for had to be my valve. They could not sell anything else within five years I guess it was.

Groueff: I hope you had the patent.

Hobbs: Yeah, I had the patent some time before, of course. That was one of the patents I had before I went to Kellex, and one of the ones I would not give up to them.

Groueff: The valve, yeah.

Hobbs: That patent has certain features, like this tubular seat. It has certain other things, but I took everything that was good and needed in the atomic picture, and put in some real things and some other things that was also neat which was not needed in the steam valve. That is the difference. You do not have to have a steam valve quite that tight, although it is important. But that is the basis.

Well, I write that letter Sunday, goes in special delivery so that when the same man that left his job at noon and mailed something to me gets an answer when he walks in the office on Monday morning. In other words, I knew that time was a real thing. So [my] time did not mean a thing.

Back at the time I first got into the valve picture, I had already put in more than twice as much time on the atomic project – half of which I paid for. Crane, Kellex, did not pay me for anything for six months. Then they only paid for half of that time. The reason that I mention that is that the United States government is trying to claim now that all those inventions belong to them, because Crane built them. But I not only had to design it, but then I had to force them to do the right job and then I spent time. I kept on spending week after week. Every other week I would be in Chicago supervising the construction. You see it was not one valve. It was a whole series of valves.

Groueff: And they were different and hundreds or thousands of them?

Hobbs: All different in dimensions. Yeah, there were thousands of them.

Groueff: Thousands of them. And very different dimension and different shapes?

Hobbs: Oh yes. And for different services. I think all together there was 65 different valves. Each one had to be different. We even designed – as I had done either before or since – the valves for a regulator company that had a regulator contract with the Army to furnish the regulator valves. I designed those regulators and all so that they would use the same body for the regulators that they used for standard manual operation, for automatic.

And that, of course, is a very valuable thing for an operating unit – and also so that you can take any valve and put a regulator on it. You do not have to have a special. That is nice too. And even the big valves, where we operated with motors. Crane says that’s what their standard practice is, and they would not build them any other way, they had to put all the motors on all the valves in Chicago and then ship them to Oak Ridge. I said, “Nothing doing.” The best motor operators were made in Philadelphia by the Limitorque Company.

Groueff: What company?

Hobbs: Limitorque.

Groueff: Limitorque.

Hobbs: Limitorque. In other words, there is a limit on it, so that the motor does not tear the valve up when it gets to the bottom or top. I think it has another name too, a gear company: Philadelphia Gear Works. Philadelphia Gear Works is the one. One of Skog’s men was in on this picture, because he was the electrical man and he kicked like a dickens about one thing in particular.

There was another company, the Cutler-Hammer Company in Milwaukee, that built valve operators too, but they were different. They were not as good as the Limitorque. In other words, I saved just on the motors themselves, the motor operators, and I made these so that they could put a motor operator on any one of these big retractable disc gate valves. Any time. Start out hand operated. They want to make it a motor operated or remote control some time, they could do it.

They shipped one motor for each size of valve to Chicago. They tested it, and also tested the conversion piece that they put on. Some of these motors, on almost all of them, were located not even on the same floor with the valves. We had an operating room above, and I put the motor operators on the top of a small flagstaff, so it could wiggle around any way it wanted to within a certain limit, so as to let the pipe move without putting any strains on the things.

Groueff: On the valve, yeah.

Hobbs: In other words, I had two pipes, one inside of the other. One of them attached to the body and the other attached to the stem. And the push and pull were concentric. You could go around the corner, and push and pull, and still make it work, although naturally we did not recommend anything except straight.

But getting back to this illustration I told you a while ago, where we free designed quite quickly. I never saw or heard any whimper of any kind about wanting to go ahead with the other valves from anybody. We got into production quick. Why? These new valves were very much simpler. We made them out of ordinary steel pipe, nickel-lined, nickel-plated. The parts were nickel-plated. They were made of steel plate. The whole valve weighed about 25 percent as much as the other valve, and cost less than 25 percent.

Groueff: Wow. Yeah, yeah.

Hobbs: So the Crane contract, which had been made for $25,000,000 for part of the valves for Oak Ridge, just the first big batch they got out.

Groueff: It cost them?

Hobbs: $25,000,000. They got for a little over $6,000,000. But the big thing is you did not have to use a whale of a lot of alloy or nickel. You did not have to wait for the plates to be clad down in Lukens [Steel Company], Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, and shipped out. And big presses and all kinds of stuff and just –

Groueff: And you did not use any lubricant?

Hobbs: Oh no. No, absolutely not.

Groueff: It was all moving without any –

Hobbs: As far as the lubricant is concerned, we had guides there that were made of a bronze. Which previous experience had told me if you have a high-lead bronze, you can operate it dry with a pretty good load on her without having any galling.

Groueff: The bronze serves as a –

Hobbs: As a lubricant. It has lead in the bronze itself. I had previously seen in New York at the Grand Central Palace a demonstration of these special leaded bronze bearings, where they had the shaft running. The bronze was red-hot and the visitors going along could light their cigarettes on the red-hot bronze and still the shaft was not damaged. I had had a problem in connection with pulverized coal. I did not mention that back in the early days, when I went from stokers to pulverized coal. I pioneered that in Pittsburgh. I wrote a paper on that and got a Silver Medal on that. And that perhaps was one of the reasons that the Diamond Alkali [Company] wanted me, because they had pulverized coal in there.

Both the President of the company and this Vice President – you see, the deal was made when the President was in Europe. He had gone to Europe at that point for the Vice President that hired me. And they had both attended a meeting at the William Penn Hotel where the ballroom had been filled listening to my lecture on this pulverized coal. I spent about $50,000, I think, on building a special boiler and a special pulverized coal at our big power station. I told our people that pulverized coal was not practical, but that we could not wait, we should not wait, for other people to develop it. It had possibilities. It was like the gas burners, if you follow theory through and made the practical thing so that you could use it.

That became the basis, and when I built this largest boiler in the world, I used pulverized coal in Pittsburgh. Then, when I went to Painesville, the first thing I did was to take four of these old stoker-fired boilers, and threw out the stokers and made a boiler. I think the old ones were 500 horsepower and the new was 1,200. Two 500s plus 200 horsepower more of tube surface in a certain arrangement, in a pulverized coal much bigger furnace, was the answer to that story.