[Interviewed by S. L. Sanger, from Working on the Bomb: An Oral History of WWII Hanford, Portland State University, 1995]

I lived in the barracks from December ’43 until March. To me, it was fine. Lots of people, they gambled and stayed out all night and things like that, but that wasn’t my cup of tea, as you might say. I enjoyed the barracks life. I had a roommate, a very congenial young man, and I enjoyed eating in the messhalls. Quite a few of the construction workers were kind of a rough bunch. Quite a lot of drinking although I didn’t see too much personally, but I heard about it, and they had fights and ruckuses. I suppose I was sort of naive, and I called myself a good church member.

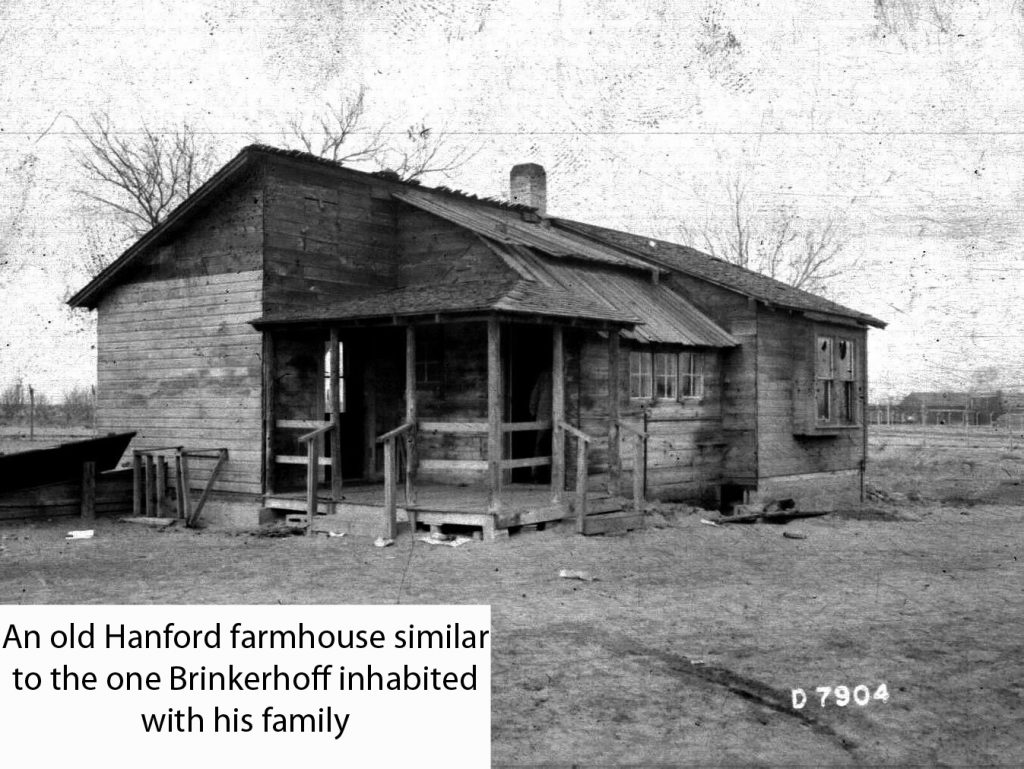

My family came up in March of ‘44 and we got a three bedroom farmhouse. They had a few houses in real nice shape out on the perimeter of the Hanford Camp and we rented one of those. We lived in the farmhouse for about six months. The house was about half a mile south and east of the camp, and I got to live in it because I bugged the housing authority. I was just a fireman, but I had four children, two boys and two girls, from age 1 to 10. They finally said if I would sign a contract that I would move with five days notice if they wanted to tear the house down, I could have a house.

As soon as operations started in July of ‘44, I transferred to the power department in 100-B Area. The power department had responsibility for furnishing all of the cooling water for the reactor, purifying the water and running the settling basins and filters. Also, we had the power house, to generate electricity in case of a power failure, it was coal-fired and was always on ready standby. It was always going, we always were generating some power, but it was put back in the Bonneville power system.

I stayed at B for six weeks, then I transferred to D, and stayed there for about 15 years, until D shut down. I was there when the boiler in the power house started up, and I was there the day they shut it down. My job was cleaning the grates and making sure everything was monitored. We had boiler feed pumps to feed water to the boiler and we had to clean the grates, they were stationary, old ones that had to be cleaned twice a day.

But, to get back to the farmhouse we lived in that summer. When we were there, there were lots of orchards left. Anyone could pick all they wanted. Where we lived, we had everything, apples, apricots, peaches, pears, plums, cherries, all around our house. We had a little irrigation ditch so we raised a real nice garden.

There was no electricity out there, no inside facilities, an outside toilet. Our water was brought to us each day in a barrel with ice in it. We lighted with coal oil lamps. My wife washed clothes on the washboard. We used wood and coal for fuel in a stove. The rent on our farmhouse was exorbitant. If I told you how much it was, you wouldn’t believe me. Seven dollars a month for the rent and a dollar extra for the furniture.

The bus rides were all free, our kids could go wherever they wanted. Whenever I got a day off, we would take the bus up to the river and take the ferry across and walk on the north side of the river. We would go on a Sunday. I’ll tell you what my wife said then, and she said it all these years. That she enjoyed that summer at Hanford in ’44 more than any summer she put in during her married life, and we lived together more than 52 years before she passed away. It was so peaceful and quiet out there. Nobody come to bother us, and we had acres of orchards, a garden spot, and we could walk down along the river.