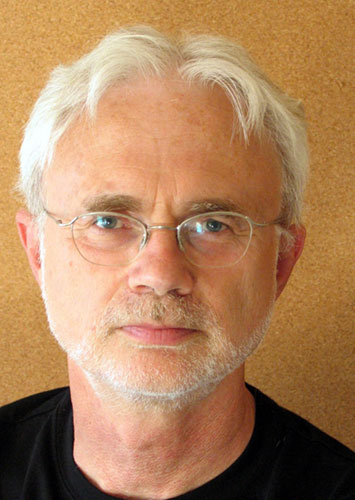

Cindy Kelly: The next speaker is John Adams, who is a composer, as you all know, and composed most recently an opera about the Manhattan Project, “Doctor Atomic,” which opened in San Francisco last October [2005]. We are absolutely thrilled to have him here, as an artist who has grappled with the deeper meanings and expressed them most dramatically in music and in theater in this opera. I’d like to invite John to come and get wired up and begin.

[Applause]

John Adams: Thank you very much, thank you.

I’m a performer and a conductor, and podiums are usually something you stand on, so I’m very restless on a stage. I’m delighted to be here. It’s particularly a special honor to be amongst so many of these brilliant minds who—from what we’ve heard this morning—always see the bigger picture, are not the kind of “tunnel vision” that has become kind of a cliché in our society. People who are deep thinkers. But at the same time, very broad thinkers.

I realize this is a rather unique idea: a composer, a person who deals in sound, and essentially, I think of my craft as one of feeling—that music, above and beyond everything else, is the art of feeling. An example of that is that you can take a scene, let’s say a scene in a movie, and you can completely color the emotional and psychological content of that scene by the use of music. You can make it seem ironic, you can make it seem maudlin, you can make it seem heroic, you can make it seem romantic, all by the choice of the tones that the composer puts to it.

I don’t think people, when they watch television or when they go to the movies, are quite aware of just how subversive and how incredibly precise on an emotional level music is, and how it really dictates the way we feel about something. In a sense, that’s a description of my job.

I was drawn to this topic—actually, it was a suggestion by a woman named Pamela Rosenberg, who is the General Director of the San Francisco Opera. About 1999 or so, she came to me, she had just taken the job, and she said, “I want to commission an American ‘Faust.’ You’re the composer, there’s no doubt in my mind. I think the topic ought to be Robert Oppenheimer and the Los Alamos story.”

I wasn’t particularly interested in the American “Faust.” I thought that “Faust,” while in a sense might be a universal image or a universal myth, that it really was very much a German—or certainly a European—myth, and that we Americans, we really have our own separate mythology.

We can respond to the great myths or to something like Goethe, but we also have Gettysburg and Marilyn Monroe and the JFK assassination and Iwo Jima and the Lindbergh flight, and, certainly, the atomic bomb. I just named these off the top of my head. They’re events, they’re personalities in our culture who have risen to the level of mythology, of being myths. By a “myth,” I mean that it’s a single image, or a single story, or a single theme, which constellates a whole array of impressions or consciousness in our lives as a social unit. That particular social unit I’m talking about is, we as Americans.

The atomic bomb, I think, is the ultimate American myth. First of all, because it’s so captivating. It’s visually captivating. Who hasn’t stood in rapt awe and attention, flipping a book, looking at images of atomic explosions? They are beautiful, in an awesome way. They capture our attention, and they express something that is both conscious and unconscious. I think if you have something that has that ability to touch you, on both the conscious level and the unconscious level, then it is a kind of a myth.

I had already composed several operas about—if not American mythology, certainly really important key events in American life. I suppose, in a sense, I was ripe for taking on this story of Los Alamos and Oppenheimer.

My first opera was an opera called Nixon in China. It’s a funny opera, but it’s also an opera that really takes on some of the great themes of our lifetime. Certainly, the most important of which was the collision of two ways of seeing human existence: the market economy represented by Nixon and capitalism and the Rotary luncheons and small business loans and everything that sort of 1970s Republicanism represented. Or, on the other hand, a communist welfare society, with all its utopian dreams and its terrible dysfunctional realities, represented by Mao.

That was an opera in which I could utilize these very delicious characters. Writing for Mao Tse-tung was really fun, and writing for Richard Nixon was equally enjoyable. I used them to actually approach subjects that were very, very deep in the American psyche.

The second opera that I wrote was—I wrote in the early ‘90s—called The Death of Klinghoffer, which was an opera about the hijacking of the Achille Lauro. You probably remember the hijacking that occurred. A very small group of four young Palestinians sneaked onto an Italian cruise ship—interestingly enough, with Norwegian passports—and took over the ship and, in the end, murdered one single American handicapped, elderly, retired Jewish man.

I used that opera as a way of trying to get into the darker psyche of America—not so much in its response to terrorism, but in its response to the “other,” the alien, which for American society seems to have become amplified even more over the last ten years or so. Of course, they view us as the alien.

I had a predilection for dealing with these topics, and they’re big, big, gigantic topics. To talk about the atomic bomb, to talk about the moral implications of it, to try to even go near the technology of it, is a very tall order, especially for someone who rarely got above a B+ in math in high school and was very nervous being around scientists, until I realized most of them only want to talk about music.

After Pamela Rosenberg suggested this to me, I went and I read one book and saw one film, and I’m so glad that those were the first two documents that I consulted because they were both of such overwhelming influence on me, and they were both so articulate, and they’re both by gentlemen that are here in the audience.

One, of course, was Richard Rhodes’ Making of the Atomic Bomb. I’ve always wanted to tell Richard I thought it was really an unfortunate title, because the book is so much more than about the making of the atomic bomb. It’s really about a history of physics in the twentieth century, starting with [James Clerk] Maxwell, long before the discovery of the neutron, and going up to the war and dealing with the human elements of it, the scientific elements of it, the political elements of it. It’s an extraordinary piece of work, and it will remain long after many other books of popular science have been forgotten or superseded. This book will, I think, remain.

The other was the film The Day After Trinity by John Else, who has become a very, very close friend in the meantime. A remarkable film, a really elegiac piece of work, very deeply humane. I’m sure you’ve all seen it, those long recollections by Frank Oppenheimer about his brother [J. Robert Oppenheimer] in the countryside here. And then these looming images of Alamogordo and the grainy sort of surreal, not-quite-corrected color of the blue sky, and the images of the Trinity bomb being hoisted up. At that point, I realized that this was the right subject for an opera.

The thing about opera is that it is such an absurd art form. If you think about it, you come into this hall, the lights go down, and these very, very bizarre things happen. People get out on the stage, and they start singing in this strangely arch, highly exaggerated way. Frequently, the text is unintelligible, and the stage changes in a way that’s very unlike film. Because it’s fundamentally a musical experience, it’s also therefore fundamentally a profoundly emotional experience, which is why people who go to a bad performance of an opera are angrier than anyone in the world. A bad opera performance is worse than a terrible car crash, because every imaginable aspect of your being has been offended. On the other hand, when it works, it’s an overwhelming experience, because it involves you on all kinds of levels.

Doctor Atomic was an opportunity to create a work that challenged the audience on an intellectual level, certainly on a psychological level. What were these people really thinking? What was the pressure like in those last twenty-four hours, before the Trinity explosion? Certainly, on a moral level, what was the import of the invention of this? It was touched on earlier this morning in some of the comments by the symposium members.

Then, on just a pure sensual level, music is a very sensual experience. I was able to make music that gave a sense of a storm blowing across the desert, of scientists arguing, and of the final countdown and detonation of this weapon.

I’m sorry I have to stand here today and tell you all about this and not be able to play any for you, but unfortunately, due to union rules of the San Francisco Opera, I’m not allowed to play any recording until the time comes out that there’s actually an official, commercial recording, which hopefully won’t be too long. But I can tell you a lot about how I created the work and also the very interesting libretto, which was compiled principally by my collaborator, Peter Sellars, who’s a very, very deep-thinking and very creative stage director.

The first issue when you’re writing an opera is, “What’s the timeline going to be?” It’s not like a novel, where you can stretch out and have a very long timeline. An opera has got to take place in roughly two to three hours. Of course, I always start out with way too much, much too grandiose an idea of what I’m going to cover.

The original thought was that Act I was going to be Los Alamos, the work on the bomb, arguments between Groves and Oppenheimer, the young socialist and communist members of the team coming in with a petition from Leo Szilard and causing all kinds of problems and headaches for Oppenheimer, and then the movement of everybody down to Alamogordo and the test. For some reason, I thought I could accomplish that in an hour. Then, the second half would be ten years later, and Oppenheimer’s horrible trial and embarrassment in Washington. Needless to say, as we got more focused this all got boiled down to a very, very concise period.

Act I, there’s one scene that takes place about roughly two weeks. Ot’s the end of June 1945, and we’re in the lab in Los Alamos. The set was designed by Adrienne LaBelle. She came down here, she spent months looking at photographs, and she said, “You know, it’s really amazing. For such a top-secret project, there’s an astonishing amount of photographs and materials available. They really did document themselves very well.” Maybe that’s why General Groves always seemed to be in a bad mood, because he was always worried about security.

In the first act, we see the chorus—they are the workers—and there are these strange vacuum tubes and heatsinks and generators and all kinds of devices for the final push of creating the work, all the engineering feat that goes on. The chorus comes out.

What I want to say about the libretto for this opera: it is an extraordinary libretto, because every word in it was actually said by somebody, or it at least was written by a firsthand account. It’s a compilation of quotes and comments that people made, including Edward Teller, Robert Wilson, Leo Szilard—we quote the letter that he wrote to Teller—Oppenheimer himself, and a lot of military personnel. What we did is, we just went through reams of material and picked little phrases, and then Peter Sellars put them together.

The very first chorus in Doctor Atomic has the workers, and they’re singing a section from a book I found, which was written by Henry DeWolf Smyth, and it was published in 1945.

But I used this the introduction to this book, which is called Atomic Energy for Military Purposes, and I set this to music.

The chorus comes out and says:

The end of June 1945 finds us expecting from day-to-day to hear of the explosion of the first atomic bomb devised by man. All the problems are believed to have been solved at least well enough to make a bomb practicable. A sustained neutron chain reaction, resulting from nuclear fission, has been demonstrated. Production plants of several different types—

—I do this with a sort of newsreel music, the kind of music you heard in old 1950s black-and-white newsreel—

—Production plants of several different types are in operation, building a stockpile of the explosive material. We do not know when the first explosion will occur, nor how effective it will be. The devastation of a single bomb is expected to be comparable to that of a major air raid by usual methods.

That was certainly an understatement.

A weapon has been developed that is potentially destructive beyond the wildest nightmares of the imagination, a weapon so ideally suited to sudden, unannounced attack that a country’s major cities might be destroyed overnight by an ostensibly friendly power. This weapon has been created not by the devilish inspiration of some warped genius, but by the arduous labor of thousands of normal men and women working for the safety of their country.

There’s a kind of a pride, a sense of derring-do, and almost a kind of Hardy Boys, “We’re going to go out there and solve this problem.” That’s an example of how we incorporated actual original material into the libretto.

Dealing with Oppenheimer and Teller and Robert Wilson, who we chose as a very important character, was really not only a challenge but also a tremendously rewarding thing to do. So much has been said about Oppenheimer, his uniqueness, his highly cultivated background, his astonishing transformation from being a kind of arrogant, difficult, brilliant young professor to the sort of father figure and extremely adept political person that he became upon being appointed here [at Los Alamos].

I reveled, I took so much pleasure in making an operatic character of Oppenheimer, because I realized that he was a person of enormous artistic sensibility, as well as being a great scientific mind. One of the most important things was the awareness of how much Oppenheimer loved poetry. You all know the story—which I imagine is true—that he carried a volume of French poetry, particularly Charles Baudelaire, with him and he had it on the test site. He said later that he named the site “Trinity” after the sonnet by John Donne, “Batter my heart, three-person’d God.”

Instead of making Oppenheimer say the usual blather that you’ll get in operatic libretto, what we did is that we gave Oppenheimer poetry. At many moments when he’s off by himself—he’s not arguing with an uppity young graduate student, or having to calm General Groves down—but he’s off by himself, and he’s really contemplating how the world is going to change, he apostrophizes in the words of these great poets.

I did set that great John Donne poem at the very end of Act I. Oppenheimer’s alone, there’s been arguing, there’s been the first terrible storm, this unexpected electrical storm that blew up over the test site. He’s finally alone, and this huge plutonium sphere, hanging like literally sort of Damocles over the test site, is illuminated in the background. Oppenheimer sings this poem, “Batter my heart, three-person’d God.”

Batter my heart, three-person’d God, for you

As yet but knock, breathe, shine, and seek to mend;

That I may rise and stand, o’erthrow me, and bend

Your force to break, blow, burn, and make me new.

It’s written in that very elusive, symbolic language of the elusive beast in metaphysical poets. But it’s a poem, a deep poem, of tremendous torment of the soul. The speaker asks that God come and literally batter him, assault him, knock him to the ground, almost kill him, to make him new because he feels that his soul has been usurped, usurped by a dark power. He makes the image of being like a city that’s been taken over by some evil invader. He’s pleading with God to do this violent thing to him, so that he may become whole again.

I think the fact that Oppenheimer could operate both spiritually as well as intellectually on both levels—both as a great scientist, both as somebody who’s delivering the goods for the war effort—but at the same time, able to look beyond that and express it by an awareness of a sonnet like this, is really an extraordinary testament to the man’s universality.

When I was preparing to write the opera, one of the key books was The Collected Letters of Robert Oppenheimer. I don’t know how many of you have looked at them, but they’re really wonderful because they start when he was a teenager. He entered Harvard at the age of sixteen, and immediately started taking graduate course. To kick back and relax, he used to write sonnets and exchange sonnets with his friends. We get this idea of just an incredibly, intensely brilliant young man who was equally able in the physical sciences as well as in literature.

Then, as you read further on in these collected letters, you see the world-weariness, you see the weight of the world coming onto Oppenheimer. In the end, he’s writing these letters to the President of the University of California complaining about his mistreatment in the faculty promotion and things like that, or having to deal with senators. Those letters are an amazing description of the arc of his life.

There are three main events that happen in the opera. One, of course, is getting the “Gadget” ready, arming it, detonating it, and the fact that this storm came up. Of course, every opera composer loves an opportunity to orchestrate a storm, so I got the best of all possibilities in terms of dramatic tension. Not only did I get a nice big electrical storm, but I got an atomic bomb sitting there, waiting to go off.

Robert Wilson, who wasn’t one of the top echelon of players, but he was a young physicist, very committed. I’m sure there are people in the room here who knew him. He also, at the time, was very much a committed socialist, if not a communist. John Else actually had a lot of recorded interviews with Robert Wilson. John generously made those available to us, things that weren’t included in his film.

Wilson describes the fact that some of the young scientists at the very end became very alarmed about the possible use of the weapon, particularly on civilians in Japan. If there are people here who were there and know that this is not the case, I’d love to know. But from my reading and from my understanding, there were several petitions that were attempted to be sent from particularly the young scientists, who believed—naively, probably—that it would actually get onto President Truman’s desk and not be intercepted by some general or some diplomat.

The first thing is this letter by Leo Szilard, which was written and which Teller quotes in his memoirs. I don’t know how many of you have read this letter, but Szilard wrote this letter. Here’s Szilard, the person who actually got [Albert] Einstein to get FDR’s attention to actually start this whole thing. Szilard, by the end of the Los Alamos period, right before the Trinity test, is now concerned with what he believes to be an immoral use of the weapon on civilians.

I set this for Edward Teller to sing. These are Teller’s own words, and getting the rights to use them was not easy because I had to contact the Teller estate. He had already died at that point, and their first answer was, “Absolutely not.” They just assumed that Teller would be trashed in this opera, that it would be another embarrassment and “Dr. Strangelove.”

I actually had to contact his daughter, Wendy Teller, and explain what I was doing and send her the libretto. She wrote back, and she said, “Well, I think the opera’s basically anti-science, but you can use it anyway.” I don’t know why she thinks it was anti-science.

I guess it really had to do with the issue of—the main theme is whether scientists are responsible for the ultimate use of weapons, or whether they’re simply doing what the government asked them to do and letting the Army and the government make the decision on the use of it. It’s something on which I never came to an ultimate decision myself.

Here’s Szilard’s letter, which I set for Teller.

Many of us are inclined to say that individual Germans share the guilt for the acts which Germany committed during this war. Because, they, the scientists in Germany, did not raise their voices in protest against those acts. Their defense that their protests would have been to no avail hardly seems acceptable, even though these Germans could not have protested without running risks to life and liberty.

We scientists—

Meaning “We here,” particularly at Los Alamos—

working on atomic power are in a position to raise our voices without such risks, even though we might incur the displeasure of those who are present in charge. The people of the United States are unaware of the choice we face, and this only increases our responsibility in the matter. We alone who have worked on atomic power—

He means on the bomb—

we alone are in a position to declare our stand.

Oppenheimer responds:

I think it is improper for a scientist to use his prestige as a platform for political pronouncements. The nation’s fate should be left in the hands of the best men in Washington. They have the information which we do not possess. Men like [General George C.] Marshall, a man of great humanity and intellect. It is for them to decide, not for us.

Then the idealistic young Robert Wilson, who is barely out of graduate school, responds by saying, “Actually, I’m organizing a small meeting at our building. The title is called ‘The Impact of the Gadget on Civilization.’”

Oppenheimer responds to him, “I saw that announcement. I’d like to persuade you not to have it. I feel that such a discussion in the lab, in the technical area, is quite inconsistent with what we are talking about here.”

Wilson responds very angrily to Oppenheimer, and you realize that Oppenheimer is a god to Wilson. He just can’t believe that suddenly Oppenheimer would be, as far as he’s concerned, mouthing words from the Pentagon.

Wilson responds, “These questions are not technical questions. They’re political and social questions. And the answers given to them may affect all mankind for generations. In thinking about them, the men on this project have been thinking as citizens of the United States vitally interested in the welfare of the human race.”

Oppenheimer responds, “I might warn you that you could get in trouble if you had such a meeting.”

It goes on and on, and then Wilson comes out with this petition. This petition really existed, I didn’t make it up. It was a petition that he circulated amongst the workers here.

To the President of the United States:

We, the undersigned scientists, having been working in the field of atomic power. Until recently, we have had to fear that in this war, the United States might be attacked by atomic bombs, and that her only defense might lie in a counterattack by the same means. Today, with the defeat of Germany, this danger is averted, and we feel impelled to say what follows.

Atomic bombs may well be effective warfare, but attacks on Japan cannot be justified until we make clear the terms of peace and give them a chance to surrender.

That’s really the moral crisis that goes on in the first act of the opera. I think what’s interesting is that Oppenheimer, at this point, really felt that he agreed with [James B.] Conant that the bomb should be used in the way it was, and Conant’s famous recommendation that was that it be used in this area that was both an industrial area, but where there were a lot of people—in other words, civilians—so it would make the maximum psychological impact. It’s a kind of unknowable moral crisis.

I’m very deeply aware that two people this morning mentioned the fact—I think it was Mr. Hunter said that his father had gone home to Florida on a short break, and he was going back to what he thought would be his sure death invading Japan. There were many others that felt, if the atomic bomb hadn’t been dropped on Hiroshima, that the war would have cost many more lives.

Now, of course, there’s a lot of historical research pointing to the fact that the Japanese were intensely trying to arrange a negotiation. The main problem had been this one term, “unconditional surrender,” and they were afraid that the emperor would be humiliated. Unfortunately, the Japanese apparently were using the worst possible conduit for a peace probe, which was the Soviet Union. It’s an unknowable thing.

There’s so much to talk about, and I’m not going to go on for too much longer. But I do want to say one thing, which is that this opera is not just about the guys. I really wanted to make a very, very strong theme in it, not only for women, but also for the Native Americans, whose territory this had been originally, and who were here during this, but who are so often left out of the narrative.

The narrative is really one of guys, the brilliant young scientists and the Army, and it’s easy to overlook the fact that there were many women here. Not the least of which was Kitty Oppenheimer, Oppenheimer’s very complicated and emotionally explosive wife, who was obviously miserable stuck in Los Alamos and having to behave as a kind of social director of the activities here. And who herself was a scientist, and who had been married to a communist organizer in the mines in Pennsylvania, and then who had gone off to fight against Franco.

What I did with Kitty Oppenheimer—we didn’t have any quotes of her—but I invested in her what Goethe calls the “das Ewig-Weibliche,” the sort of “eternal feminine.” She becomes a kind of Cassandra figure, a woman who understands on a much more intuitive level the human impact of what’s going on. We found an amazing poet, who lived during that same time, a woman named Muriel Rukeyser. We put Muriel Rukeyser’s wartime poetry into Kitty Oppenheimer’s character. It’s very profoundly affecting to hear these pronouncements about the dark side of her awareness.

Also, there’s a character who is a Tewa Indian, who was Kitty’s maid, the Oppenheimer’s maid. As the countdown goes on, as the opera ends, we have the test site, we actually are on the desert floor in Alamogordo. The bomb is there, the scientists are sweating bullets, they’re arming it, Groves is waiting for the weather, he’s screaming at the weatherman. Off on the side, back in Los Alamos, we see Kitty and her Tewa maid taking in this event from a distance, but knowing its import. We get this very, very powerful feminine theme, and people with an awareness of a different cosmology as the Native Americans had. Then over on the side, the sort of super, super scientific activity, the ultimate end of which is profound violence.

The opera ends in a very unique way. All during the writing of this opera, I was completely freaked by how I was going to end the opera, because trying to orchestrate an atomic explosion would just be laughable. That’s something for Stephen Spielberg to do, but an opera composer? It would be just really silly. But I knew that it would be a cop-out not to have the detonation.

I worked it out basically by creating a gigantic orchestral countdown, where the orchestra becomes one clock, and then another clock going at a different pulse and another pulse, until you get a whole orchestra of clocks counting down and then getting faster and faster. Of course, as that happens, time slows down—just like the quote from I. I. Rabi this morning that Richard Rhodes said, how that last two minutes was the longest of his life. In effect, the last two minutes in my opera before the bomb goes off lasts twenty minutes. I stretch time, and then the bomb goes off.

Peter Sellars has an astonishing moment where everyone is hunkered down on the stage as the bomb goes off, and this brilliant orange-red light floods the entire opera house. All of the characters, the scientists and the military people, they all look up into the audience, and you, the audience, become the bomb. There is this “Opera house does rock and roll” for several minutes.

Then, the very, very last thing is, coming from loudspeakers way off in the distance, the voice of a Japanese woman. What I did is I found some records of quotes that survivors had said. Actually, some of them were from the John Hersey book [Hiroshima]. One is just of a woman asking for water, and you just hear that over and over again, just this Japanese woman very, very quietly and very, very respectfully asking for water. That’s the very last thing you hear in the opera.

If there are any comments or questions, this is such a rare opportunity for me as a composer to be among scientists. Maybe some of you who actually knew these people or were at the event, I’d love to engage in the few minutes that we have if anybody has any questions or comments.

Unidentified Male: Speaking of the upcoming recording, much of what you’ve talked about seems very, very visual and very audience-interactive. That seems like it’s going to be difficult to put out in a recording. Are there any plans for a DVD?

Adams: Yeah. The question is: “It sounds like it’s so profoundly visual; will there be a DVD?” There probably will at some point. Operas are phenomenally expensive to produce. I would say, probably after the Pentagon, the opera company loses more money with more glee than any other activity I can think of. But, I would assume at some point.

I frankly think that opera put on film or on DVD is just very weak. You can’t get the same experience. But, as an audio experience on a CD, I think it really works because you can just close your eyes and use your imagination.

Good. Okay. Well, thank you very much.

[Applause]