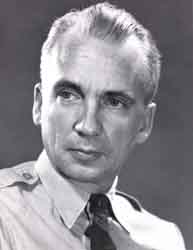

Martin Sherwin: This morning I am making arrangements to interview Norris Bradbury in Los Alamos, New Mexico. January 10, 1985.

How would you characterize the major problems that [J. Robert] Oppenheimer had when he first got the job as the administrator for Los Alamos? Or at least, when you came on?

Norris Bradbury: Let’s get this clear. I did not come on the scene until quite late. The place started in 1943, spring of ’43, as you know. I turned up here in the summer of ’44. I was a latecomer. I was in the Navy at the time, and I did not come up here until after Admiral Parsons, Deak Parsons, came. I worked for him back at the Naval Proving Ground.

Sherwin: What brought you here?

Bradbury: He did. Naval orders.

Sherwin: I see. There must have been some—

Bradbury: Well, there was a reason. I was a physicist. I had been teaching at Stanford up to the start of the war, but I was also a reserve naval officer. As soon as the war was even in prospect, I was called to active duty. I went active duty, I guess, in January of 1944, and I was sent here. Not here, Admiral—well, he was then Captain Parsons. In the course of things, he disappeared, and in the course of things, I disappeared with him. [Laughter] Parsons was right here.

I was sent here in a blue suit and khakis. That is how I happened to get here. It was a surprise to me, I have to say. We were shown ordnance research at Dahlgren. That is the U.S. Naval Proving Ground. It is near Fredericksburg. It is south of Washington. We were doing ordnance research, and he was chief of the experimental department, Admiral Parsons. I did not know what was going on here at all. I did not know about all this. I was faintly aware there might be something going on, but that is all.

Sherwin: What kind of physics did you do? Your PhD was on what?

Bradbury: I did my PhD and most of my research was in the field of gas ions, not nuclear physics. I did maybe one or two papers on nuclear physics with a physics bloc as a junior author, but my basic field is conduction, electricity and gases, gas ions, things of that sort.

Sherwin: Did you work with [George] Kistiakowsky?

Bradbury: Let’s get on to that, then. I was sent here. I guess it is reasonably common knowledge. By the later part of ’44, it had become clear that plutonium was going to be no good for the gun-type weapon. It had too much of a background [neutrons]. It had to be a faster assembly business than that. There was an idea sponsored and well-developed by Seth Neddermeyer, that you might be able to assemble things not in a lineal fashion with a gun, but in an implosion circle system. For reasons not known to me—it was a brilliant idea and Seth had it, but he was not going to work very hard at it. This is all I can comment on it. He only worked with a few people, but all that simply wasn’t enough. Because if you didn’t do that, the whole Hanford effort was going to be a total waste of time.

Oppie decided to beef up the implosion idea. I do not know when he brought Kistiakowsky in. I don’t have that date in mind, but I came afterwards. Kisty got admitted, I suspect, at Parsons’ suggestion. [On Bradbury:] “Here’s a physicist, who knows about physics. He had done some administrating, and then of course had his career as a ‘naval officer.’ He knows something about HE [high explosives] because he had been doing ordnance. Why don’t you get him?”

“I’ll get him if you want.” [Laughter]

This is in uniform, and you go where you are told. So I was suddenly directed to report to Albuquerque. I did so, and there was my old pal, Captain Commodore Parsons. I was driven up here and he says, “Here is what we want you to do,” probably in defiance of all the security regulations.” [Laughter]

Sherwin: They had you already.

Bradbury: They had me anyway, so I was not going anywhere. [Laughter] Well, I was not entirely happy to come here. I was happy at Dahlgren.

Sherwin: Were you married at the time?

Bradbury: Yes, and with children. Two children, and one on the way. I had a sort of dismal premonition that once I got here, I would never get away, and that turned out to be right. [Laughter] I did not know much about the project, but I suspected we would not be on loan very long if we were on loan then. Certainly if the project was successful, we would not be on loan very long, and so I would never get away, short of total incompetence or something. [Laughter] That is how I got here, and I never did get away, as I predicted. I guess I have never regretted it. We had fun.

Sherwin: When you were here, what—

Bradbury: You asked me questions I have skipped, I am sorry to say, about what was Oppenheimer’s first problem?

Sherwin: I will get back to that. You were brought here because of your explosive background?

Bradbury: And physics.

Sherwin: And background in physics. But you also said administration?

Bradbury: I was the first [inaudible] experimental officer at Dahlgren. That means I had a number of the reserve scientists under me, quite a number, and several departments of the experimental office.

Sherwin: So primarily, you were working as a physicist?

Bradbury: Oh, I would say primarily I was working as a boss. You better know, if you want to be a boss, you better know what you’re bossing. [Laughter]

Sherwin: Now, what part of the impolsion device were you particularly concerned with? The lenses?

Bradbury: The HE. Well, all the HE. HE lenses, and what other parts there were. Things that detonated the lenses.

Sherwin: The first infusers, and the electronics. At some point in this latter half of the Los Alamos days, you must have gotten fairly close to Oppenheimer?

Bradbury: Actually, no. Not particularly. I saw him from time to time, but I was working for Kistiakowsky. I saw him at the weekly whatever they called them, the meetings, the colloquium. Everyone went to the colloquium, but he had a senior staff meeting.

Sherwin: The administrative—

Bradbury: I don’t know what it was called. I did not go to it. [Laughter] Kisty went, but I didn’t. I went occasionally when Kisty wasn’t here or something. I was not very close to Oppie, when you come right down to it.

You asked for his first task. One of his first tasks was to assemble the staff, and he did that incredibly well. The thing that struck me primarily about him was his knowledge of people and his knowledge of what was going on. By one channel or another, I remember several occasions when we would get something, some nice results, a nice picture, a nice demonstration of something up in X Division or one of them. Oppie would hear about it probably from Kisty and ask me, “Man, I hear you’ve got some nice results. Could I see them?” You would trot up and show him your photographs or whatever. Always interested, always knowledgeable.

Sherwin: Would you say that he was so knowledgeable, that he actually contributed to suggestions of how to proceed?

Bradbury: In our field, in Kisty’s and my field, I would say no. That wasn’t his field. Where he did contribute, and that again is a piece of ancient history, very strongly was perhaps in intuition or common sense or whatever. A few weeks—and I’ve forgotten was “few” means, one or two or three or something—before Trinity was supposed to be shot off, there was a [inaudible] experiment done here, which made it look as the implosion process was absolute hogwash. It wouldn’t work. In spite of all the evidence they had accumulated before that, this one experiment—

Sherwin: Run by whom?

Bradbury: Beg your pardon?

Sherwin: Who ran it?

Bradbury: I have forgotten. I think that [Luis] Alvarez was probably in change of it, but a lot of people were involved. It was a very large full-scale experiment. Bright idea, in principle. Except it did not work worth a damn, and the results, which it gave after the event, could have been predicted that it couldn’t work. This could not do what it was supposed to. The brains that designed it [laughter] were somewhat abashed afterwards. It couldn’t possibly have been useful. This was not known until some time after the experiment. Now the experts, including me I suppose, had different opinions of how long it was.

My recollection is that Oppie heard of the results, and was wondering whether he should call off the Trinity explosion. The results were so disastrous that if they are correct, it would likely deny everything we know or thought we knew. He talked to me about this. I don’t know where Kisty was, but I was there. He talked to me, what did I think?

I said, “It denies everything we know, and I simply cannot believe it because we have got pictures, electronics, and everything says that what we are doing makes sense.”

Oppie took that sort of vague advice and said, “Okay, I don’t think I know what’s wrong here, but I think I will ignore that and go ahead with the shot.” Of course he did, and he was right. Sometime afterwards—sometime, some people say it was a few weeks, some a few days, a month—what was wrong with the experiment was suddenly illuminated, and should have been thrown out before it was done.

Sherwin: So in other words, the failure of that experiment, or the results of that experiment, didn’t add on July 16th?

Bradbury: It merely gave you a deep sinking feeling in the stomach. “My God, if that experiment is right—”

Sherwin: But you found out that it was wrong?

Bradbury: Later on.

Sherwin: Before Trinity?

Bradbury: No.

Sherwin: After Trinity?

Bradbury: After Trinity.

Sherwin: Oh, so that—

Bradbury: Whether it was a month after or a few days after, but what I am saying is my recollection—

Sherwin: It was definitely after Trinity.

Bradbury: Don’t get me wrong, I think it was definitely after Trinity because I remember it that way. I think you can find people who say it was before Trinity. [Hans] Bethe said, “It must be wrong.” Now maybe he did, I don’t know. These things get a little vague after forty years. I remember Oppenheimer talking about it and talking about it to me. But not in the sense of diagnosing the experiment—to see if I can see any reason why the implosion experiments, which we had done, could be so badly represented or so badly done, that this experiment should be believed.

Sherwin: So through the end of the war, you were sort of once removed from Oppenheimer?

Bradbury: Twice removed, I would say.

Sherwin: By Kistiakowsky?

Bradbury: Once by Kistiakowsky, and then I worked for Kistiakowsky.

Sherwin: Okay. Now, I want to see if you remember a few things that occurred here in the spring of 1945, roughly. There is that famous meeting that I think was initiated by Bob Wilson about a discussion of the future of the Gadget, or the impact of the Gadget.

Bradbury: I wasn’t there. [Laughter] I was not involved in it. Because I was engaged in quite [inaudible] tests that were interesting and important, but my step in working for Kisty was to get the Gadget ready for Trinity, particularly the explosion parts, the implosion parts and diffusing parts, firing parts, that sort of thing. From then on, my job was to get the implosion gadget ready for Nagasaki, to start getting the bombs ready for the bombs after that. I had nothing to do with the gun gadget.

Sherwin: Right.

Bradbury: It didn’t matter where it was going. I was busy at a much lower level of concern. I was at that time mostly working for Parsons, I suppose, who wasn’t involved in these high-level, what becomes of everybody now. So I cannot give you any clue. I do not even know what it was; I wasn’t there.

Sherwin: Were you thinking of staying in the Navy, or going back to Stanford?

Bradbury: I had hoped very much to get back to Stanford. We had built a house there, and I was anxious to get back to my research. I had been propositioned to stay in the Navy and turned it down, figuring very easily that I would never get beyond Rear Admiral, and would be like to be Chief of Naval Research [laughter] if I had stayed in uniform. Civilians who become naval officers don’t get very far, when you get right down to it.

I never considered very seriously staying in the Navy. I did consider very seriously going home. In fact, my mind did not get changed until Oppenheimer called me up to the office one afternoon at about four o’clock and said, “Would you be interested in being director of the laboratory?”

Sherwin: Do you remember when that was? Was that a week before he left, or months before?

Bradbury: I would say it was about three days before he left.

Sherwin: Which was when?

Bradbury: Middle of September. My official tenure as director began after I got out of uniform. They had to get me out of uniform before I could be a director. That meant I had to go out to California and be separated. That Parsons arranged very rapidly, but it still killed a week. So I was acting director from about the 18th, 19th, or 20th of September to 1st of October. I think if you look at the history, it is somewhere [inaudible], but up to that time, I was acting.

Sherwin: Did you ever find out anything more about the process by which you were kept here? [Laughter]

Bradbury: Yes, most of it was unfortunate. [Laughter] I don’t know what you are going to do with some of this stuff. Oppenheimer, I guess, looked around. He had asked [Robert] Bacher first, I am sure. Bacher said, “Nothing doing.” Bacher was always his right-hand man. Bacher said no, he wanted to get back to Cal Tech.

Kisty and most of the other people wanted to get back. Kisty wouldn’t do it for a variety of reasons. He and Oppenheimer never got along worth a hoot, really. Kisty would not do it anyway.

I guess among the people who were available, I was probably as senior [inaudible] at that time as anybody. Apparently, Oppenheimer checked it with [General Leslie] Groves. As far as I am aware, Groves shrugged his shoulders and said, “Okay, if that is what you think,” or words to that effect. I didn’t know Groves to speak of. I suppose I had met him, but I didn’t know him at all. The thing Oppie neglected to do, unfortunately, was a serious breach. He did not ask the University of California, [laughter] who was charged by contract with getting the director of the laboratory.

Sherwin: He was having [inaudible]—

Bradbury: Yeah, but that was an incredible mistake, and it didn’t occur to me either. It was an incredible botch on my part, but then I did not know how the place was run. In fact, the first thing I did when I got into the accursed office was to ask Dave Gall, I think, for a copy of the contract. I had no idea what the contract was. The contract at that point was a one-page [laughter] letter. That’s all it was. But this infuriated the University. I’m sure the president of the University—

Sherwin: [Robert Gordon] Sproul?

Bradbury: Sproul then, but his—

Sherwin: Underhill?

Bradbury: Bob Underhill, who was his chief man here. They were madder than hell, and were going to [inaudible] up the contract. This I know from Bob, who later on became my very good friend.

Sherwin: From Bob Underhill?

Bradbury: Bob Underhill. He and I are very close friends. They were going to pull the thing out, but [inaudible] said, “We’ll give the poor bastard a little while to see what he does.” [Laughter] So they politely left me alone.

Of course, I did not realize much of this. I did not realize that I had joined the family until the contract came up for renewal. Then Bob Underhill, with whom I had had increasing contact, said when he came down to negotiate the extension of the contract [between Los Alamos and University of California-Berkeley], “By the way, I want you in on this negotiation.” By that time, he explained to me, “Well look, we have kept hands off of you and so on, but now you are part of the family. You are doing fine. It is going to be your contract. You better damn well get in and help negotiate it.” So I spent the next few days negotiating a contract. From that time on, Underhill and I became very good friends.

Sherwin: So let me ask the same question of you that I started off about Oppenheimer. What were the major problems that you faced?

Bradbury: The same problems he did, actually. He had to pull together a staff. I had to keep a staff. First of all, I had to keep a staff in the face of—everybody in the world at that time was in love with science. The kids here who only had BAs wanted to get PhDs. The kids that had PhDs wanted to get instructorships. The kids that had instructorships wanted to get assistant [inaudible], and so on up the line.

There was a tremendous sort of exodus, perfectly understandable. My job for awhile was just to keep the damn place together. It went down to about, in the course of the next twelve months, went down to 1,400 people.

Sherwin: Would you say that Operations Crossroads had anything to do with the effort to keep things together?

Bradbury: It helped. It helped a little bit. It was a pain in the neck, but it helped.

Sherwin: What got it going?

Bradbury: Admiral Parsons.

Sherwin: Whose idea was it?

Bradbury: Parsons. Deak Parsons.

Sherwin: Now did Parsons stay here?

Bradbury: No. He went right back to Washington to become the head of some fancy research company the Navy had. I’ve forgotten his title. But it was called the Naval Weapons Evaluation Group, or something like that. He was head of that among other things. God, he might have been on the MLC [Military Liaison Committee]. I am not sure at this point.

It was his bright idea, and of course with all respect, he is now dead. He could see the Navy being outclassed by the Air Force, probably not by the Army. [Laughter] But he was going to get the Navy into the sack of kindling, so he dreamed up Crossroads. The first time, it was set for sometime in the spring of ‘45. We could not possibly make it. It was just too quick. I did not have the people, but I did get a lot of people to stay on for a summer operation.

Sherwin: It was dreamed up in—

Bradbury: So ’46.

Sherwin: ’46?

Bradbury: ’46, I’m sorry.

Sherwin: So that fact that it occurred in—

Bradbury: In ’46.

Sherwin: May or June, ’46?

Bradbury: Right. But like I say, it was originally scheduled for some time in April/May, but we just could not make it by then.

Sherwin: It was postponed about a month?

Bradbury: Something like that.

Sherwin: Do you remember when it first came up? Did it first come up November, December, January?

Bradbury: About then. I remember meeting with Groves and Parsons and everybody, when Groves fought like a fiend to have all the Naval ships that were supposed to be exposed in Bikini full of fuel. [Laughter] For obvious reasons.

Sherwin: With barrels of fuel?

Bradbury: No, fuel tanks. Not barrels of fuel, fuel tanks, filled. It was a long argument. It went on half the day, and finally a compromise was reached. Parsons won, of course. [Laughter] And Groves wanted them full.

Sherwin: There was [inaudible] in reverse.

Bradbury: Right, sure. They finally compromised. They would be half-full.

Sherwin: Now, one of the curious things about it to me is that it was initiated by the Navy. The idea was to show that the Navy could survive atomic attack.

Bradbury: Let’s give them more credit that. What they would have to do to survive an atomic attack. I mean, what is the problem? They did discover some problems they had not thought of, really. One of the problems was all the stacks of any oil-fired ship has great big screens of them. These, of course, just flew right in and took everything out beneath. They were armor plate screens. When that was discovered, some of their people were surprised. The experiment was somewhat unhappy because the bomb did not go quite where it was supposed to, so you kind of missed the target a little bit. But the damage, generally speaking, wasn’t as bad as you would have thought.

Sherwin: Now they dropped the bombs beneath the surface of the water?

Bradbury: No, the second bomb was lowered beneath the surface of the water.

Sherwin: Lowered?

Bradbury: Lowered. It was not dropped.

Sherwin: But there were no airplanes?

Bradbury: In that shot?

Sherwin: In that shot.

Bradbury: That was Bikini Baker. No, that was suspended from a surface ship, from a tug or something. Dropped down through an open hatch. That was to see what you did to hulls, and I think there were a few submarines involved in that, if I recall correctly.

Sherwin: You were at the Trinity site?

Bradbury: Yes.

Sherwin: Have you followed the various literature and writing about Trinity, that sort of thing?

Bradbury: I see some of it. I get a little fed up with it, frankly.

Sherwin: Why do you get fed up with it?

Bradbury: A little fed up with it. [Laughter] Sorry to discourage you.

Sherwin: Why? That’s okay.

Bradbury: It has been done time and time again.

Sherwin: That’s right. The question that I had—I did not want to ask you to go through it again because there is so much of it all over the place. Are there any things that you know of or you have read or heard of that you think are just fundamental errors?

Bradbury: No.

Sherwin: That are being perpetuated?

Bradbury: No. I would say it has been adequately reported, from my point of view. Again, I have to say that my personal concern with the Trinity shot was to get that Gadget assembled up on top of the tower, and assemble it on top of the tower. I assembled it at the bottom of the tower, and then get the detonators on it and get them hooked up, and then make sure than nobody monkeyed with the pesky thing while I had control.

Sherwin: You sort of sat there?

Bradbury: I sat there. Up until it was clear that nobody else was going to be allowed on top of the tower. All the people were putting up experiments nearby, so one would—off. I would not let anybody come up unless I was there, because I didn’t want anybody monkeying with it. I was responsible for that thing. Even inadvertently, somebody might brush against something. As I stayed there until the ladder was blocked off. There was one delay; I forget now again precisely when this occurred. Probably the night of the 15th. A cable had been broken in filling, ditch filling, that had to be exhumed or replaced.

Sherwin: How did they confirm the break?

Bradbury: Well, you knew where it was. I mean, the gadgets—the ionization chamber or something wouldn’t work. It couldn’t get to zero. You lose that cable, and you just dug it up and you found it. What they had done, was they had—people that are not skilled at [inaudible]. Instead of when you put coax down a ditch, you snake it. Because if you don’t snake it, if you just put it across, the bottom is never flat, so if you turn it, it breaks because it’s apart. That is something that none of us [laughter] masterminds ever thought of.

Sherwin: There you go. When I am to bury stuff put in my backyard now, [Laughter] I have learned something.

Bradbury: Well, give it a little snake.

Sherwin: Do you remember where you were?

Bradbury: Yes, I was a long ways away. I had nothing to do with the center, nothing there of course. I had nothing to do with the firing point. I mean, in building it up. I was through. My job was done. I was up on the hillside about ten miles away, I guess. I was told many times, I was dead tired for quite awhile.

Sherwin: Don’t tell me you slept through it.

Bradbury: No, but I damn near did. Somebody woke me up. Well, there was a reason. It was raining. I was pretty certain, “This thing is never going to go off tonight, so I am going to go to sleep.” Somebody woke me up though. I did not sleep through it. Sorry, can’t add that to your story.

Sherwin: What about when you heard about Hiroshima? And Nagasaki?

Bradbury: Well, I don’t want to sound cruel. There was general jubilation. I had nothing to do with that device. I knew Parsons did. Parsons was on that flight. But there were sure [inaudible] hill parties and celebration. They did not last too long.