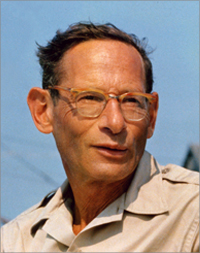

Martin Sherwin: I’m interviewing Robert Serber at his home in New York City. Date is January 9th, 1982.

Let me just begin at the beginning and ask you, how did you get to Berkeley? Why did you go there?

Serber: I got my degree at Wisconsin with [John] Van Vleck, and that was ’34. You didn’t have very many choices of what you can do. But I got a National Research Fellowship, which, if I recall, there were only five of them available that year. That was a year when the new membership of the American Physical Society was thirteen.

Sherwin: Thirteen people in it? In 1934?

Serber: Thirteen in 1934. I mean, it was really alone. The other day, about six months ago, I was looking for a birth certificate or something in a drawer, and I came up with a diploma for that fellowship and it was signed by the committee. It was really an amazing document. I have it framed in my office. [Abraham] Flexner was the chairman, and there was [Robert] Millikan and Compton.

Sherwin: Arthur?

Serber: Arthur Compton and [Roger] Adams and [Floyd K.] Richtmyer and [Theodore] Burkhardt and [Gilbert] Bliss.

Sherwin: Just everybody.

Serber: Everybody. Then [Isador I.] Rabi saw it, and he said, “Those guys didn’t let any power out of their hands.”

Sherwin: That’s right, if one was doing it, the others had to do it to make sure they can watch.

Serber: That’s right. They wouldn’t even give a fellowship without them doing it for themselves.

Sherwin: That’s right. Yeah. So in ’34, you got the fellowship, and why did you pick—?

Serber: I didn’t pick Berkeley. Van [Vleck] suggested that I go to work with [Eugene] Wigner at Princeton. Started to drive east from Madison. My wife and I, both families were in Philadelphia, we’re going to Philadelphia then to Princeton. But we stopped to go to the Ann Arbor summer school, which of course has quite a role in the history of American physics.

Sherwin: Yes.

Serber: Oppie was there. He has an appealing character. After listening to a woman coming somewhat friendly with him, we changed our minds.

Sherwin: Turned around [laughter].

Serber: Right. Turned around and drove out to California instead.

Sherwin: That’s a great story. Let’s sort of focus on that for a minute. What would the dates be?

Serber: That would be the summer of ’34, was the summer school.

Sherwin: Right, but I mean would it be June or July?

Serber: It was probably July for the summer school.

Sherwin: Okay. Now, how did you stop by? Did you need an invitation to do that?

Serber: I don’t think so.

Sherwin: You just knew about it?

Serber: I think I just showed up.

Sherwin: Yeah. Who else was there that summer?

Serber: Let me think. R. H. Fowler was there, and I remember [David] Dennison and [George] Uhlenbeck. Let me see, who else was lecturing there? There were a lot of people there. I remember Fowler and Oppenheimer were lecturing.

Sherwin: Do you remember the subjects that they were focusing on?

Serber: Fowler was lecturing on quantum statistic and [inaudible] solid state application. But most of the discussion was about the Dirac theory.

Sherwin: Okay. Was this something you were particularly interested in?

Serber: No, it’s something I hadn’t known anything about. I mean, I knew about the Dirac equation, but not about what was going on in the problems they were work—what they were actually worried about were things like the Klein paradox and the meaning of negative energy sites. But then, I had been working on atomic and molecular problems.

Sherwin: What did Oppenheimer talk about? Do you recall?

Serber: Not very specifically.

Sherwin: Yes, of course.

Serber: Except it was about the properties of the Dirac equation.

Sherwin: Oh, I see. He was focusing on that. Do you remember the first time that you saw him or heard him?

Sherwin: Ah, yes. The Dennisons were teetotalers, huh?

Serber: Well, it was in the Midwest. In those days, it was sort of frowned on.

Sherwin: I see.

Serber: I remember when we first went to Illinois, the local liquor store had a truck that said “Candy” on it.

I remember my wife and Oppie, him, eyes meeting. That was the first I remember of any spark passing between us, and we began to get friendly that afternoon.

Sherwin: I see. Your wife’s name was Charlotte?

Serber: Charlotte.

Sherwin: How long were you there, before you made up your mind that Princeton was second-best?

Serber: Oh, I don’t know. We were there about a month or something. During the course of the month, I asked Oppie if I could come out and he said, “Sure.” As a matter of fact, it turned out that of the five people in theoretical physics that got a National Research Council Fellows, three of them went to Berkeley as I did.

Sherwin: As a result of this summer school?

Serber: No, no, no.

Sherwin: Or, just two of them were going there anyway and you changed your mind?

Serber: Yeah.

Sherwin: Who were the other two?

Serber: Ed Uehling.

Sherwin: Oh, I talked to him. He’s in Seattle.

Serber: And Fred Brown.

Sherwin: Fred Brown.

Serber: He was somebody that dropped out of physics.

Sherwin: Oh, I see.

Serber: But I heard many years later that he became very successful in some associated field, starting a company or something.

Sherwin: Now, things were much simpler in those days. You said Oppenheimer wanted you to go there, so—

Serber: Oh, it wasn’t completely simple, because I wrote to the National Research Council and they said I could change, provided Wigner agreed. So we drove east to see our family and then went down to Princeton. As a matter of fact, it turned out that Wigner had been in Europe all spring and was still there. His acceptance was a purely formal thing. He had gotten a notice and just signed it over. But not being there, the secretary said, “Well, why don’t you go see Ed Condon? Maybe he can give you the release.”

Sherwin: Condon was at Princeton at that time?

Serber: Condon was at Princeton.

Sherwin: I didn’t know that.

Serber: Now, we discovered he wasn’t at Princeton; he was at his place in New Hope. We drove out to New Hope and found Condon sitting. He was sitting under an apple tree drinking, and gave us a couple of drinks.

Sherwin: Real drinks?

Serber: Real drinks.

Sherwin: Not lemonade.

Serber: He said, “Sure, go to Berkeley. I think it’s a good thing to do.”

Sherwin: So you then turned around. This is probably close to the end of August?

Serber: Yeah, and we had an old Nash that we bought for I think it was $120, and it did very well. It got us as far as Rodeo.

Sherwin: So it broke down there?

Serber: We got that close. Of course, in those days nobody owned more than you can load into a car anyway.

Sherwin: Yes.

Serber: We had left it to be repaired and got into Berkeley. We went up and met Oppie in his office. He turned us over to Melba Phillips, who took us around, found us a small apartment to stay in.

Sherwin: So you lived there. What was it? A flat?

Serber: Yeah, it was an old house that had been made into three or four apartments in it, one or two on each floor.

Sherwin: Right. Then the work began. Could you describe what other graduate students besides Melba Phillips were there at that time? Was Philip Morrison there?

Serber: No, no, that was later.

Sherwin: That was later.

Serber: No, this was—

Sherwin: Uehling was there?

Serber: Uehling.

Sherwin: Brown and?

Serber: [Leo] Nedelsky.

Sherwin: Nedelsky.

Serber: Glen Camp.

Sherwin: Is Camp still around?

Serber: I don’t know.

Sherwin: Okay.

Serber: Let me think. I don’t remember. I heard something about him. I asked somebody, but I have forgotten what the answer was.

Sherwin: Okay. Are there any others you remember?

Serber: Arn Nordsieck was in there.

Sherwin: Who was that?

Serber: Nordsieck.

Sherwin: Nordsieck.

Serber: Yeah, and Rodell. Though I’d have to go through and see the ones I’ve already mentioned. Nedelsky, Camp, and Uehling. [Leonard] Schiff wasn’t there yet, he came a little bit later. [Charles] Lauritsen.

By the way, nobody called him “Oppie.” I mean, Oppie was something that came later. It was Opje in those days.

Sherwin: They actually did call him Opje?

Serber: Yeah.

Sherwin: O-P-J-E.

Serber: Yeah, that was from his—

Sherwin: From Holland, yeah. Did people call him that or Robert?

Serber: In Pasadena, it was Robert. In Berkeley it was Opje.

Sherwin: Did his students call him by his first name?

Serber: Yeah.

Sherwin: Okay. Is that the way he introduced himself?

Serber: No.

Sherwin: He introduced himself as Robert Oppenheimer? But very quickly people, got the Opje?

Serber: Well, it’s the way he always signed himself in letters to friends.

Sherwin: Yeah. Friends from Berkeley, or also in Pasadena?

Serber: I don’t know.

Sherwin: He was Robert, yeah.

Serber: Well, it’s the way he always signed himself in letters to me.

Sherwin: Yeah, yeah. Do you have any of the early letters?

Serber: No.

Sherwin: No. I had heard that they have disappeared. It was a painful thing to hear.

Serber: Yeah. Well, it was discretion.

Sherwin: I see. Did you burn those, or throw them out?

Serber: We burned them before going to Manhattan Project.

Sherwin: To Los Alamos?

Serber: No, to Berkeley.

Sherwin: To Berkeley.

Serber: Well, it wasn’t the Manhattan Project then. Actually, it was on the payroll of the Met Lab at Chicago, but working with Oppenheimer in Berkeley for a year before Los Alamos started.

Sherwin: Now, when you say it was discretion, why is that? Was there a lot of political content?

Serber: Nothing that anybody reasonable would consider subversive. But our opinion of the FBI and so forth wasn’t—we thought they might interpret them, well, as they would have.

Sherwin: Yes, indeed. Why don’t we talk about that for a while, since we’re on the subject? You got there in the fall of ’34 and you were there until ’38. How would you characterize or talk about the non-scientific activities of those years? There was always a social life, clearly, in Berkeley, and that revolved around Oppenheimer. Why don’t you just talk about that, and I’ll follow the story into political activities.

Serber: Well, you know about the general social life of Oppie and Frankie, and people over to Jack’s for dinner after the seminars.

Sherwin: Do you remember the first time you did that?

Serber: Well, no, not specifically, no.

Sherwin: Okay.

Serber: It was a fairly often thing. There were parties at various students’ houses and then Robert gave them up at his apartment, too. Occasionally, maybe once a month, there would be a party somewhere.

Work went on in the day and at night. Charlotte would come up with me and we would frequently spend the evening at Oppenheimer’s, work until 11:00, 12:00, 1:00, and drink and talk. Sometimes we would go out to the movies, that kind of thing. But the Spanish War was beginning, and the political—

Sherwin: That’s ’36. You mean there was no discussion before ’36?

Serber: Oh no, there was quite a bit of political discussion. Let’s see. When did Oppie’s relatives come from Germany?

Sherwin: The Friedmans?

Serber: Yeah.

Sherwin: Yeah.

Serber: And his aunt Hedwig [Stern]. That must have been about ’36 or something like that. He was quite aware of what was going on in Germany, because his family was involved. There was talk about the things in general. Not much domestic politics, but what was going on in the world.

Sherwin: But before ’36, was there—

Serber: There was no activity. But when the Spanish War started, then the Medical Aid Committee for Spain started in Berkeley. Charlotte was the secretary.

There was a lot of activity, money raising, mostly by way of cocktail parties and having auctions.

Sherwin: Was Charlotte always political involved? Is that how she became secretary?

Serber: Her father in Philadelphia was in the Philadelphia Socialist Party and had been involved in left-wing activities for years and years. Her home in Philadelphia was the general atmosphere.

Sherwin: The three of you were close, as Oppenheimer was to a lot of his students and their wives. Was she a significant part of his political education? Did she often bring up these subjects, even before ’36?

Serber: No. A political part before ’36, I mean, came up. It’s bound to, unless you’re completely closed in from the world, but it was a very small part of the total. It wasn’t stressed in any way. People generally think it was Jean Tatlock then that did the most to needling Oppie about these things to increase his awareness. That’s what everybody thinks.

Sherwin: Yeah. I hadn’t known about Charlotte’s activities, and it just occurred to me that that might be something that deserves elaboration.

Serber: Well, I don’t think that was any real influence, no.

Sherwin: Okay. Now, some of the things that were going on before the Spanish Civil War. There was the Japanese war in China, and there was a great deal of concern about that, of Japanese imperialism. Was that ever a subject that you remember coming up?

Serber: No, I don’t remember it.

Sherwin: Okay. It might have?

Serber: Yeah, I mean, it was nothing—

Sherwin: [President Franklin] Roosevelt had been in office only a very short period of time when you arrived at Berkeley. Was there any talk about the New Deal?

Serber: Well, I’m sure there was, but not very much.

Sherwin: Okay.

Serber: I mean, compared to what you would have expected in New York, I think there was a lot less on the West Coast.

Sherwin: Right. Okay.

Serber: West Coast was a lot more isolated in those days than it is now. Traveling was much more difficult, for one thing.

Sherwin: Sure. Did you know Jean Tatlock, by the way?

Serber: Yeah, sure.

Sherwin: Okay. Now, let’s talk about her for a few minutes. There’s some very good stuff in this interview about her, if I can just put my finger on it. There it is. Of course, another influence, you say, was Jean Tatlock, whose views were quite far into the left. Jon [Else] asked who she was, and you describe that, and then there’s a very good summary about Jean’s psychological problems and the relationship between Robert and Jean. I think that it’s really the most useful and penetrating comments that I’ve heard about that. I’d like to see if you would elaborate on it. Perhaps if you just looked at what you said there. Now, what I’d really like to do is sort of focus in on this and see how much more you can recall about this relationship in terms of her problems. Did you know her at all?

Serber: Yeah, yeah.

Sherwin: She was at a lot of parties, I would assume.

Serber: No, no, she wasn’t involved in the parties at Robert’s with the students and that bunch. No, she was never involved in that.

Sherwin: Okay. So how did you know her?

Serber: Well, she was a good friend of Mary Ellen Washburn, who was Robert’s landlady up there at Shasta Road.

Sherwin: Right.

Serber: We used to see her at Mary Ellen’s occasionally, and these things.

Sherwin: How would describe her?

Serber: I’m trying to remember where else we saw her. The times I remember are mostly up at Mary Ellen’s.

Sherwin: Okay. Could you try to provide, in a sense, a composite recollection? Would it be sort of sitting around, just chatting?

Serber: Yeah, yeah. She was fairly tall and very good-looking, and actually looked quite composed at any social gathering. I don’t know whether it was literally manic-depressive case or what, but she did have these terrible depressions.

Sherwin: She had had them even in that earlier period?

Serber: Oh, yeah. That was presumably the cause of all these problems between her and Robert.

Sherwin: How would you describe their relationship when you knew them both?

Serber: Robert always kept that part of his life separate from all—

Sherwin: From his students.

Serber: My relation to him—our relation—was different than the students, you understand, because we were a lot closer than most of the others. He would talk about things to us, and we saw a little bit of his various girlfriends and so forth. But not to be able to tell you anything about how the relations actually went, except we would gather from him that they were up or down and he would be depressed some days because he was having trouble with Jean.

Sherwin: Now, can you recall anything about Jean that would be useful for understanding their relationship? He obviously was very taken with her.

Serber: Well, she was a very intelligent girl and I think really attractive.

Sherwin: And clearly full of activism and life.

Serber: Sometimes.

Sherwin: I see. And, other times she was on the down side. Do you remember any instances where she was talking about social issues?

Serber: No, it’s too long ago.

Sherwin: I’m not surprised that you don’t, but I certainly thought it’s worth asking.

Serber: I never knew her well. Probably a dozen or two dozen times I spent an afternoon or an evening or so. But I don’t remember anything really specific, except a general impression of certainly being left-wing more so than the rest of us.

Sherwin: Right. Now, you said in the Else interview that Kitty [Oppenheimer] knew about this relationship between Robert and Jean. In what sense did you mean that? When Robert went off to comfort her in these kinds of situations—let me ask this. Was Robert concerned that she might commit suicide?

Serber: Yes, I think he was. I know when she did commit suicide, Mary Ellen called up to tell me to tell Robert.

Sherwin: Mary Ellen?

Serber: Washburn.

Sherwin: Oh, I see, okay. That’s his landlord?

Serber: Yeah.

Sherwin: She committed suicide when?

Serber: That would have been ’44 or something, ’43.

Sherwin: Okay. Everybody was already living at Los Alamos when that happened?

Serber: Yeah.

Sherwin: Okay.

Serber: Robert had already heard. I don’t know how. But he was very broken up. But, I mean, remember it was [inaudible] between us, it wasn’t anything unexpected.

Sherwin: I see.

Serber: It was clear that it was a thing that he had been worrying about. As far as seeing it, a year in Berkeley, the Oppenheimers were living on Eagle Hill, and they had a little apartment over in the garage and they lived in that garage. I remember I was driving home and I saw Robert and Jean. I saw them walking on the street in conversation a block or so from the house. It surprised me, knowing he was still seeing her. But then later on, Kitty told me that she knew all about it. Robert would tell her that Jean was in trouble, and he was going to try and see what he can do.

Sherwin: Did she ever explicitly threaten suicide or try to commit suicide before she actually did that?

Serber: I don’t know.

Sherwin: Okay. What kind of evidence do we have for establishing the case that Oppenheimer’s relationship to her was concerned with the suicide issue, in terms of her deep psychological problems?

Serber: I don’t know. I mean, I don’t know if there was any—

Sherwin: Was she seeing a psychiatrist?

Serber: I don’t know.

Sherwin: Okay.

Serber: I don’t know that there was any connection with the relations, Oppenheimer would not have made any particular difference to what happened. Of course, there was a relationship, in the sense that was one part of the whole problem, part of her whole life. But not specific, and that wasn’t a reason.

Sherwin: Right. Well, what I’m getting at is that General [Leslie] Groves and the Gray Board and all those people put the crudest interpretation on this visit and overnight stay with Jean Tatlock. This explanation that you give in the Else interview is the most sensitive.

Serber: Well, that was the way the relationship had been for several years. I’m sure that’s what happened, that Jean called up in desperation.

Sherwin: Which she had done before?

Serber: Which she had done—I don’t know frequently, but at least several times before.

Sherwin: Even when he was in Berkeley at the time, and Kitty was aware of this and that Robert would go over and walk the streets or talk to her in the living room? That sort of thing?

Serber: Yeah, I mean, that’s the way it had been, and undoubtedly this was the same situation.

Sherwin: Okay, good. Well, going back to your arrival in Berkeley and studying physics, what did the program look like in 1934? Was there immediate distinction between experimental and theoretical?

Serber: Oh, yeah, sure.

Sherwin: You’re in experimental physics?

Serber: Theoretical.

Sherwin: You’re theoretical.

Serber: Yeah.

Sherwin: Why did I—okay.

Serber: There was a distinction of who did what. Of course, we had more professional and social life. It wasn’t separate. I mean, Ed McMillan in particular was a joint part of the group, and Luis Alvarez, although not to the extent Ed was.

Sherwin: And they were working with [Ernest] Lawrence?

Serber: They were working Lawrence.

Sherwin: Did you take three courses or two courses?

Serber: No, I was a post-doc, I didn’t take any courses.

Sherwin: Oh, that’s right, okay. So, you were working on what problem?

Serber: Well, vacuum polarization. We knew that [William] Pasternak, the alleged discrepancy in the hydrogen spectrum. This is three-hundredths of a wave number. Ed Uehling was working on the hydrogen case and the vacuum polarization for us, for a Coulomb field. I generalized it to him, to an arbitrary field, what nowadays would be called a proton propagator. At first I had to learn about quantum field theory, which I read what was in [Paul] Dirac’s book, but that’s about all I knew. I had to learn a lot about that and then I had to learn what Dirac and [Werner] Heisenberg and [Leonhard] Euler and [George] Gamow, treating infinities.

Sherwin: So you audited Oppenheimer’s quantum course?

Serber: No.

Sherwin: No. You just talked to him about it?

Serber: I took a few weeks of reading, and then Ed did his half and I did my half of the problem. Then we worked on things like the self-energy electron and tried various regularization schemes, and found out we couldn’t make any of them work consistently. Meanwhile, nuclear physics connected with a radiation lab in Berkeley and with Charlie Lauritsen’s work in Pasadena. Did nuclear physics. Particularly there was the Oppenheimer-Phillips process at that time. Some of the most important things that came out were the isotopic spin selection rules and the analogue states, which by the way, were completely forgotten for sixteen years and rediscovered only after the war.

Sherwin: Well, that happens. Would you say that the kind of work Oppenheimer did in some way related to black hole research?

Serber: That was somewhat different. I don’t think it was forgotten. I mean, it just didn’t find an application until later. But [inaudible] nuclei, that was about the first thing I did in nuclear physics. That also was not noticed until rediscovered by Wigner a year later.

Sherwin: I see.

Serber: It was Willie Fowler’s dissertation.

Sherwin: How would you describe to a lay audience the general thrust of physics at this period of time in Berkeley, the kinds of things that the Oppenheimer group was interested in? The particular keys that you were looking for, for unlocking issues?

Serber: First of all, the electrodynamic thing. Now, Oppenheimer and his group did the whole bunch essentially, independently and simultaneous, like the Bethe-Heitler formula and all that. Oppie would publish a letter one week and then within a month, one way or the other, the Bethe-Heitler would come out where Oppie had just had a letter, which usually had something slightly wrong with the answer. I mean, ideas were right, but the details weren’t quite worked out, and then you’d get a complete paper from Dirac giving it.

Sherwin: On all the details.

Serber: In all the details, or from Bethe.

Sherwin: Would you say that that was, in a sense, a modus operandi, that Oppenheimer was sort of a spark? You know, he liked the ideas and he would—

Serber: No, no.

Sherwin: No.

Serber: Working the same way on the problems.

Sherwin: Okay.

Serber: This is Oppenheimer. Well, it’s more a group of students. They were talking about the whole rest of the world, like half a dozen problems. Surprising that they were able to—everybody saw the same problem. What was remarkable was that Oppenheimer and his group, all by themselves essentially got something on all these problems. They had about the same time as the competition. But since the competition was dozens of people, it’s not remarkable, each one would be working on one problem and get it done in an elegant way.

Oppie’s bunch had just sort of taken the problems. They got the high energy limit of the formula, and it had not been completely worked out, and publishing things as letters. I don’t know whether it was more an American way of doing things, or just a realization. The competition was so rough, they couldn’t stop and wait to do a good complete job and write up a paper. They would always be beaten.

Sherwin: I see. Well, that’s interesting. What I’m groping towards is trying to understand the style.

Serber: Now, Oppie was extremely good at seeing the physics and doing the calculation on the back of an envelope and getting all the main factors, except the two’s and so forth right, that kind of thing.

Sherwin: Was he an impatient—

Serber: But then as far as actually finishing, doing a nice complete elegant job the way Dirac would do, that wasn’t Oppie’s style.

Sherwin: Okay. That’s what I was—I mean, it was specifically Dirac and Bethe, too, was like that.

Serber: Bethe, too. Bethe sits down and writes it out, how to calculate, and then sends it off to the journal without changing. He doesn’t write a paper. He just does the calculation, and sends it off.

Sherwin: I see. And they’re always very precise and very complete?

Serber: Very precise. Oppie was the idea and getting at about how big it is and doing a limiting case which makes it easy, and do it fast and dirty.

Sherwin: Yeah.

Serber: He’s like the American way of building a machine.