[At top is the edited version of the interview published by S. L. Sanger in Working on the Bomb: An Oral History of WWII Hanford, Portland State University, 1995.

For the full transcript that matches the audio of the interview, please scroll down.]

Book version:

BUD: I was a counter-intelligence agent at Hanford. Everybody was suspicious but mostly it was unwarranted. Everybody was spied on. I had my own network worked up, mostly women. They liked to play cops and robbers. Some of them were stenographers, or women who worked at the hotel. If I were curious about somebody at the hotel, I would ask the girl on the desk what she knew.

I never ran across a spy at Hanford. One German showed up. I pitied him. He was a craftsman and we had a tank that had to go up. It was stainless steel, which was like using gold in those days. It was about 80 feet high, and it had to be exactly plumb. They looked all over the United States for someone who could make stainless steel wedges that could make this thing plumb. And the guy turned out to be this German. He went to his work one morning, then he was on a plane and he was at Hanford. He had been in this country long before the war, but he still spoke with an accent. My orders were to see that he wasn’t fooled with. I was to shoot anybody who made any motion toward him. I had that damn Tommy gun cocked and ready to go. People thought I was pointing a gun at the German, but actually I was there to protect him. He was a nervous wreck.

CLARE: I went into the Army training center in May, 1943. That was down in Georgia, Fort Oglethorpe. I was in the WAAC (Womens‘ Army Auxiliary Corps) at the time. After that they sent us to New York. They wanted us in the Manhattan Engineer District. I learned a little bit there, and then they sent three of us to Tennessee. We worked there, at Oak Ridge, in classified files, and at the last of October, they talked about sending some of us to Hanford. I wanted that, because it was close to Portland, my home. They said no. But I wouldn‘t sign up for the regular Army unless they sent me to Hanford. Guess where I ended up? We were the only WACs at Hanford for a while.

The head of intelligence came to me and said he needed a receptionist and somebody who could type. I was tickled to death. It was a new experience, so I moved to his office at Hanford Camp. I was a secretary for safeguarding military information. After that, I worked at the military intelligence office in Richland. I was the first WAC there, and they treated me nice. Bud and I worked in the same office, and that’s how we met. I didn’t know what he did, because nobody asked anybody what they did.

BUD: I got calls at all times of day and night from informants. I told them they were working for the U.S. government, in a highly-classified job. And not to tell anybody what they did because it might get them killed. I had two old ladies there in their 60s who were especially active.

CLARE: DON’T YOU CALL THEM OLD!

BUD: They were dears, I’ll tell you that, and they gave me some awfully good information. I would just ask them and they would check it out. They knew a lot of people. They lived in a little house just outside the project. They belonged to every knitting society and blanket society. They were busy. If they came across any little thing, they told me. One story they picked up was that we were making rockets, anti-personnel rockets. They told me who had said it. I told my office this person was starting rumors and they took care of it. The guy was young, and unmarried, and he got drafted real quick.

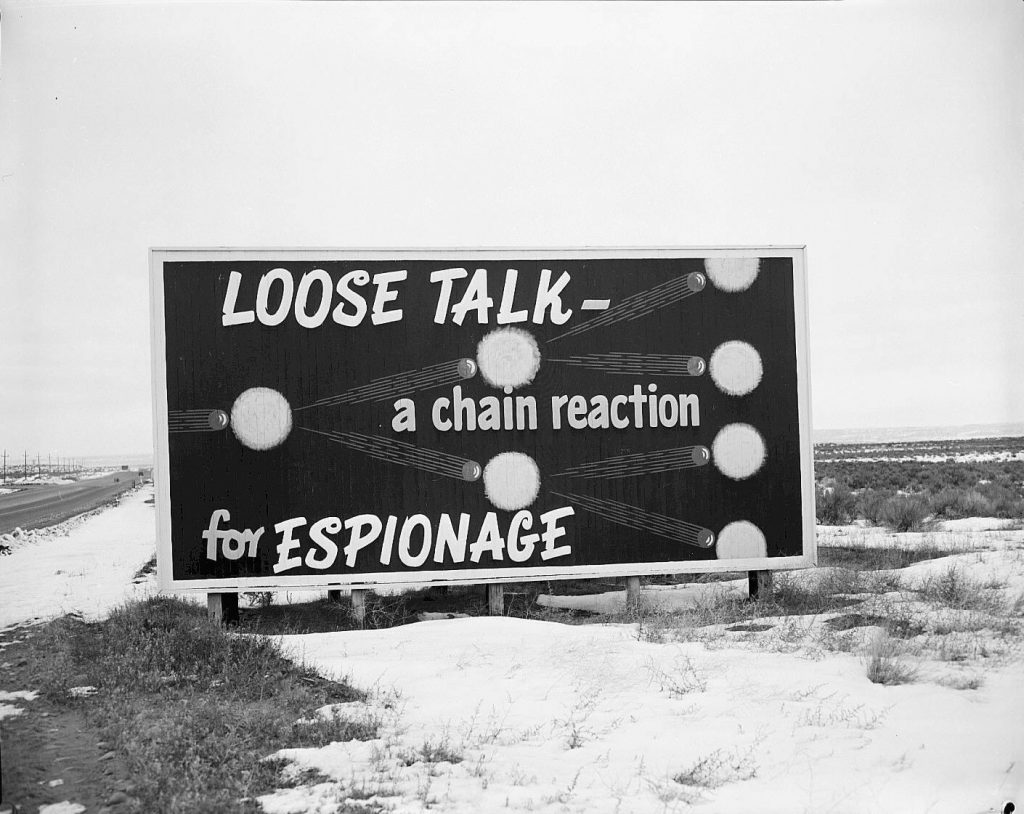

CLARE: When I was in files, I didn‘t know what was going on. But there was a job in intelligence, where each of us was assigned so many periodicals and newspapers and we had to watch for words. One of the words was “atom.”

BUD: That reminds me. I got a lot of information from files. They put me in charge of headquarters, everybody had to take their turn, answering the phones, a 24-hour service. I went through all the files. Of course, they were under lock but I could pick the locks. I found out from reading the files that they didn‘t fancy me much as an agent. Once, soon after I first hit the project, I was not invited to a party. But I put bugs in the house where the party was and I got some very enlightening information. They all hated the officers in intelligence, and they said some very uncomplimentary things about these officers. I got the agents together and I played this thing for them. I was included in every party after that.

CLARE: I didn’t know what Bud did. I thought he was the office photographer.

BUD: The regular photographer went to another base, and I had to pick up his job. Being a photographer was part of my cover. I carried a detective special pistol. I would rather have a brick. In my car was a carbine, a Tommy gun and a gas gun. I was an arsenal. I had an intercept car, a Ford, that thing would do 102 miles an hour.

We had a little plane. An artillery spotter plane. The pilot had been in Europe, and he was wounded and lost an eye. I used to fly with him every morning, to check the fence all around. It took about an hour and a half. We were looking for tracks. We never found any.

CLARE: Has anybody ever told you about the milk shakes at White Bluffs? It was just a little drug store, these people were still there and hadn’t been moved out. The officer of the day would stop at the WAGS barracks and take two or three of us up there for milk shakes. I have never tasted a better shake.

BUD: We did spot checks on telephone conversations. Not everybody, but there were some trunk lines we listened to. Maybe some colonel’s wife talking to another wife. The purpose was to find who was breaking security.

CLARE: I took my turn listening to conversations. The room was right across from the military intelligence office.

BUD: I would record a violation, and the man would be charged or scolded. For instance, there was a code name given to each piece of apparatus, and some of those professors for Christ’s sake would just in the clear say the description. We had a mechanical hand that was used to pick up objects in the separation facility. They spent a lot on that, and that damn fool used the name and mentioned delivery dates. We didn’t have conversation scramblers in those days.

CLARE: But after the Smythe Report was out, secrecy was out. (Henry DeWolf Smythe, a Princeton physicist, wrote the official government publication on the bomb, and described the project in detail. The book was published in 1945, soon after the war ended.)

BUD: Have you ever tried to get an egg back in a hen?

One thing I recall, before the bombs were dropped. I remember a Du Pont guy got up to give a speech and he said, “Folks, I can finally tell you what we are making here. We are making horses’ asses and they go back to Washington, D.C. for final fitting.” You could hear a pin drop, and then that whole crowd fell over. Everybody got drunk after the bombs were dropped on Japan. They finally found out what they were making.

CLARE: Do you remember that wild party? That was a shameful affair.

Full Transcript:

Stephen L. Sanger: An interview with Vincent and Mrs. Whitehead, May 17, 1986, at their residence in Portland, Oregon.

Clare Whitehead: We were there [Hanford] in October of ‘74, wasn’t it? It was when we took that long bus trip.

Sanger: For what?

Clare: We were on a holiday trip.

Vincent Whitehead: It’s outgrown everything we had since the war.

Sanger: Yeah, it’s a hundred thousand people now.

Clare: The old hotel was gone.

Sanger: Was that the transient quarters?

Clare: I think that’s what they called the transient quarters. We always called it the hotel.

Sanger: Because that’s where the Hanford House or—the Thunderbirds—

Clare: Yeah, there’s something else there now, and it’s way back in the river.

Sanger: What my partner and I are doing is trying to put together something that’s more interviews like this with people who were there, either as physicists, or like you, or engineers or anybody, workers. It’s kind of hard to find construction workers. They apparently have moved on, for the most part.

Vincent: When they first did the planning, they had to get the construction going. That was a must, because we were scared to death that the Germans were going to beat us. They had the heavy water plant and the basis of their design was heavy water. It was up in Norway. The British did their damnedest to destroy it. They used their planes and their special pilots and everything. It just never got there. They died. The British were after us to get going on this, but Roosevelt couldn’t see it. He couldn’t see what the hurry was. Then he saw the Axis had shifted their policy. They brought the Japanese into the war, and then we were engaged.

Sanger: How did you get into that end of the Army?

Vincent: I don’t know. I was drafted. I had just finished Camp White. I was the head of surveys there. We were just placing buildings.

Sanger: Where’s that, Camp White?

Clare: Southern Oregon.

Vincent: It’s Medford.

Clare: Honey, he doesn’t know!

Sanger: I thought you said Medford, okay. But you were with the Corps of Engineers?

Vincent: I was with the Corps of Engineers.

Sanger: Oh, you were. Okay.

Vincent: Yeah, I worked with them, and I was in the survey section. They needed somebody to spot their buildings, their roads, and their highways, everything to make a camp. Then from there, I was drafted up in Portland. I came here. Then I was sent up to Fort Lewis, and from there I went down to the Presidio in San Francisco.

Sanger: When was this?

Vincent: This was in ‘42. From there, I was put in academy, because I knew my right hand from my left, I guess. We were teaching the civilians to be soldiers. I just hope I trained enough of them to keep from being killed.

From there, the Colonel told me, “The regiment is shipping.” He says, “You’re not going. I’m not going. We’d never live through to see the shore.”

We were training hard, and we had to be kind of harsh. It was to save their life, but they didn’t see that. They thought we were just being mean. From there, I was sent down to Presidio and told I was in military intelligence and [inaudible]. They sent me down to Stanford to check out a guy down there. Then I was sent to Illinois University, not in Chicago, but in a little town in south.

Sanger: Champaign-Urbana?

Vincent: Yeah, Urbana. At that time, they were flooding the whole area with groups of soldiers that were going to be in these interrogation units. Big planning for the big push over in Europe. From there, I was shipped down to Tennessee. Tennessee had just really got going. Let’s see, it was more finished then.

Sanger: Yeah, Clinton Engineer Works.

Vincent: Yeah. I had trouble with them.

Clare: The Chicago school didn’t have anything to do with you getting there?

Vincent: No, I was sent there. They had a school in Chicago. They were training security agents for this. Down in Tennessee and for Hanford. We had to have agents in there, or the other people got their agents in there. Pretty close to ‘43, I believe. Was it fall of ‘42?

Clare: No, you came down to Hanford after I did. I went to Hanford in September of ‘43. Then you came in late winter, early spring.

Sanger: Of what?

Clare: Of ‘44.

Vincent: Yeah, I had to go to the school there and they had to have an agent in there. We weren’t out to provide the foreigners with agents.

Sanger: What did you do then in Tennessee? [Laughter]

Vincent: I was supposed to do a spot check of their security there. That damned place, I walked through there and nobody questioned me or anything.

Sanger: Oh, you just walked in?

Vincent: I just had the uniform on. I was a plain soldier, and I just walked in there. Any place I wanted to go, I had the uniform. That’s all I needed.

Sanger: That’s all you needed. So that would have been in ‘43 sometime?

Vincent: Yeah. Wait, you said it was—

Clare: I went into the Army in the spring of ‘43. Then in the fall of ‘43 was when I went into the Manhattan Engineer District. Then in the summer I was up in New York, and in the fall I went down to Tennessee. Then it was long towards the last of October when we came up to Hanford.

Sanger: Which year?

Clare: Of ‘43.

Sanger: When you went to Hanford?

Clare: Yeah. So he went to Hanford, I think, in the late winter or early summer of ‘44.

Vincent: I checked out everything.

Sanger: Then you stayed in Tennessee for about how long?

Vincent: I only stayed there about a month, and then I had to go up to the school in Chicago for their training for security people.

Sanger: What did you do then at the school in Chicago?

Vincent: I took the course along with all the other students. That was a lie. I had no more got into that place when they said, “What are they sending an agent in here for?” I was supposed to be top secret, the whole damn thing. Everybody knew what the hell I was there for!

Sanger: What did they teach you at the school?

Vincent: They started with the basics. Most of the thing was oriented against the Communists. The Communists just by then had shifted their position from being against us to for us. But they still hadn’t gotten the word to all their agents. So we were there to put the kibosh on that.

Sanger: But this was for the Manhattan Project facilities?

Vincent: Yeah, we wanted to keep that from the Russians.

Sanger: They weren’t as worried about the Germans?

Vincent: We were. They were our competitors, and we were plenty worried about the Germans. The German agents stuck out like a sore thumb.

Sanger: Oh, did they?

Vincent: Yes. When I first hit Chicago, I was told to scare one of the German agents. I was parked outside of his house. I went to the streetcar and read the newspaper over his shoulder, and I didn’t scare him one damn bit. I told the boss about it and he said, “You’ll just have to keep at it.”

I said, “What do I have to do, kick him in the butt?”

The third day was the charm. He finally got the idea somebody was following him around. I hadn’t tripped and fallen on him. Anyway, that was it. The idea was to scare him, so he’d get in communication with his boss and we could then trace the outfit. They had a mail route fixed up that went through Texas and Mexico and down to Brazil. From Brazil, they moved across the Atlantic to Africa, up through France. There was just five days difference in time. That was pretty slick in those days.

Sanger: But then you also went to school as well as tailing German agents?

Vincent: No, just that security school for the agents.

Sanger: Oh, and that had something to do with nuclear energy?

Vincent: I was checked out for nuclear energy. They wanted to know. They had inquiries about me. I was a reader of Astounding Stories. All these scientists were also story writers. You could get what they were thinking off of what they wrote. They had a plan in there about atomics. They had an editor from one of the magazines. He wrote about that. I read that. The kibosh was over secrecy. And anybody that had any mention or read anything about it, they were included in.

Sanger: So how long were you there before you went on?

Vincent: I was there about a week. I moved fast. I thought for a while they weren’t going to let people sleep. Everything was hurry, hurry, hurry, and it wasn’t hurry up and wait. It was “Hurry and get results. When you get results, here’s the next one.” In the meantime [Colonel Franklin] Matthias was touring in ‘42 for sites. Finally, I ended up at Hanford.

Sanger: From Chicago?

Vincent: From Chicago. They shipped me from Chicago back to Tennessee.

Sanger: Oh, they did?

Vincent: I had just gotten down there and they had the tickets waiting for me, and I came back. I met my so-called partner, Charles Lamb.

Sanger: L – A – M – B?

Vincent: Yeah.

Sanger: He was military intelligence too?

Vincent: Yeah. I thought for an instant he was supposed to be looking after me, but I contacted him later and found out, after the war was over, that he didn’t have any idea what my job was. He was to check anything photographic that was taken. He was supposed to put the kibosh on that, but then he was transferred out of there.

Clare: Worked in [inaudible], didn’t he?

Vincent: Yes, but then he was transferred out of there. With Vicki, whom he married.

Clare: At Hanford? He went to officers’ training school, didn’t he?

Vincent: No. They took you out of Army at the rank that you were. We’re working sometimes with colonels and sometimes with majors, and sometimes with privates. You never knew what their rank was, because you were in civilian clothes.

Sanger: What were you in the Army, when you were still in uniform?

Vincent: I was just a private in the Army. I was in plans of training for the regiment.

Clare: Yeah, but that was before you got to Hanford.

Vincent: Yeah, a long time. That was pressure too, because I had to convert these people. They didn’t know what a gun was.

Sanger: So then you went to Hanford. Do you remember when you got there?

Vincent: I remember everybody there had no use for me.

Sanger: Did they know what you were?

Vincent: I don’t know, but they were a suspicious lot anyway. Suspicion was the first thing. Everybody was looking out to see that they didn’t get buried or anything. They had those people were scared to death. They didn’t know what they were producing, or what the idea was. The head man was a major.

Clare: Gillette.

Vincent: Gillette. Razor blades.

Clare: He said why they were the way they were when he came in. The other agents, most of them had families at home, and they had been there for months without a dime of pay. You can understand why their morale was clear down in the dumps, because they were living on what little bit they could save, and on what little bit their wives could bring in with a job.

Vincent: That’s why they were in a hurry for me to get there. They thought there would be an uprising. I sent a telegram that changed that in a hell of a hurry. They got their money.

Sanger: How come they hadn’t been paid?

Vincent: Stupidity.

Sanger: They were in the Army though?

Vincent: They were in the Army. What was that lieutenant’s name? No, he was a captain.

Clare: [P.B.] Mountjoy was a lieutenant then. He got his captaincy later. It wasn’t very much longer after that that he was transferred.

Sanger: That was the reason?

Vincent: Yeah, he just didn’t do his work.

Sanger: How many men in the detachment there, the military intelligence group?

Vincent: You could never tell. We were coming and going. We had men that came from Romania and Turkey.

Sanger: You were all in plain clothes?

Vincent: All plain clothes.

Clare: We didn’t know anything about that, right in the office?

Vincent: Right. I had the safe house.

Sanger: Where was that?

Vincent: That was right in the project down in Richland. I had to meet the training. They would tell me there were so many agents coming in. They didn’t give me the names or a damn thing, but I could just watch and see. Their training showed up, and I’d contact them.

Sanger: What sort of training? How do you tell?

Vincent: If you tap one of those men on the shoulder, you were laying out on the ground. Their reflexes were just like that. You just had to do something that would call attention to yourself.

Sanger: And they would react?

Vincent: They would react.

Sanger: But then they stayed with you for a while?

Vincent: They stayed with me until they had their paperwork cleared for them, and they were sent to their new assignment.

Sanger: Which might be what?

Vincent: I didn’t know. I didn’t care. All I wanted to know was to get rid of them.

Clare: Was it days or hours or weeks?

Vincent: With some men it took weeks. With some other men, it took twenty-four hours.

Sanger: What were they doing in the interim then?

Vincent: They were stuck right in that house. They didn’t walk outside. They didn’t look at the grass grow.

Sanger: Why was it they came to Hanford for that transition?

Vincent: I can’t understand the Army’s ideas of what organization is. I just thought it was a disorganized mob, that’s about all.

Sanger: What were you doing as far as Hanford was concerned?

Vincent: I had to watch these agents. I had to see there were trainloads of people coming in. The contractors were bringing their men in. I had to watch over the setup and make sure that these people were screened. If something just didn’t look right, then I got somebody else.

Sanger: When they went through the personnel screening?

Vincent: Yes.

Sanger: What would your attention be called to?

Vincent: Somebody that was inquisitive about something, we had no use for.

Sanger: What would you do in that case then? Put somebody on them, or what?

Vincent: No, I didn’t put anybody on them. I’d just report it to my boss and he saw to them. I was so dang busy I just couldn’t fool around with that kind of crap.

Sanger: How would you find out? Would you talk to the personnel people? How would you know that somebody was inquisitive, out of all those thousands?

Vincent: There was our own security people. They condensed things. A thousand people, they were screened by the contractor. I think it was DuPont.

Sanger: Yeah, DuPont.

Vincent: They’d screen them, and if anybody stuck out they contacted our people. Then our people would screen them. Some agents, I’d have coffee with the agents. That was normal.

Sanger: Would you be called counter-intelligence?

Vincent: Yes.

Sanger: Any idea how many people like you were there?

Vincent: I was the only one of us for Hanford. I got assigned to Hanford, and other people were assigned down to Tennessee and down south. Each one came through us. It filtered through us, and then we saw to it that immediate action was taken.

Sanger: Who were you dealing with, military police or military intelligence?

Vincent: I was dealing with all of them, and I reported to Washington, D.C.

Sanger: Did you have any idea how many cases you worked on, or how many people were called to your attention for some reason? Were there lots of instances of suspicious characters?

Vincent: Everybody was suspicious, and mostly it was unwarranted. Everybody was spied on. I had my own network worked up, mostly women. They liked to play cops and robbers.

Sanger: What would they be doing normally?

Vincent: They were stenographers, people that worked in the hotels.

Sanger: So they would hear things or pass things on?

Vincent: If I was curious about somebody that was at the hotel, I’d ask the girl there what she thought.

Sanger: Did that work pretty well?

Vincent: Yeah. Put every male critter near a female and he’s interested.

Sanger: Did you ever come across anybody who seemed to really be genuinely a spy?

Vincent: Back in college, yes.

Sanger: But not at Hanford?

Vincent: Not at Hanford. We had visitors from Moscow. But our agents, they turned out every agent they had on the project. They couldn’t take a sip of coffee without us knowing about it.

Sanger: They were scientists or what?

Vincent: No, there was KGB men.

Sanger: How did you know that?

Vincent: We were told that they would arrive on such and such a train, and there was an agent with them.

Sanger: Then what would happen usually?

Vincent: They couldn’t go on the project.

Sanger: But they would be there in Pasco or wherever.

Whitehead: It was in Pasco.

Sanger: But they would be tailed and watched all of the time?

Vincent: There was a man in the room next to me at the hotel.

Sanger: Did that happen very often?

Vincent: No. It happened about three times.

Sanger: I suppose the KGB – they were trying to talk to people and get an idea of what was going on?

Vincent: We never knew what they were up to. We had no way of picking their minds. They were trained people, too, and you never knew what they would do.

Sanger: Did they know that they were being watched?

Vincent: Yes. They’d been very suspicious.

Sanger: How long would they stay? Do you remember?

Vincent: They stayed two days.

Sanger: That’s interesting. Ever any German indication there?

Vincent: No, there was only one German. I pitied him. He was a craftsman. We had a tank that had to go up. They had to be stainless steel, which was like using gold in those days. It was about eighty feet high, this tank, and they had to get it exactly plumb. They searched all over the United States for a man that could make stainless steel wedges that could make this thing plumb. And the guy turned out to be this German. He was from in the north there.

He went to his work one morning, then he was on a plane and then he was over there at Hanford. I was up there. My orders were to see that he wasn’t fooled with. I was to shoot anybody who made any motion towards him. I had that damn Tommy gun cocked and ready to go. People thought I was pointing a gun at the German, and I was there protecting him! [Laughter]

Sanger: So how long was he there, just long enough to do the job?

Vincent: Yeah.

Sanger: Where was that, out at the separation area?

Vincent: No, that was around the project where we were producing stuff.

Clare: That poor little man. I supposed he never knows to this day what he was doing.

Vincent: He was a nervous wreck. He [inaudible] would look up at me, and I was looking down at him, and I was looking all around him to see that there was nobody fiddling, because he was very important. There were weeks tied up in that damn tank. The tank was worth thousands and thousands of dollars.

Sanger: He was the only guy that could do it?

Vincent: He was the only guy that we found that could do it.

Sanger: His German background was coincidental, I suppose.

Vincent: He was in this country before the war started.

Clare: So it was just the fact that he was German.

Vincent: He still spoke with an accent. This guy says, “Say, what are you standing over that guy with a gun for?”

I said, “To see that he isn’t interfered with. And if you step on that damn walkway, I’ll shoot you.” He lost his interest! [Laughter]

Sanger: When did you say that you got to Hanford?

Vincent: It was ‘43.

Clare: It was in the winter of ‘43, ‘44.

Sanger: Somewhere around the first of the year.

Clare: Yeah, around the first of the year, before the weather started getting really hot.

Sanger: Construction was really in its heyday.

Vincent: When I came there, they were building roads before they had the houses. Sometimes they were building the roads after the houses were already built. It was at every stage of construction that you can imagine.

Sanger: Where did you live then, in Richland?

Vincent: I lived in Richland, and I was right in the middle of the women’s area. They had it divided up according to sex.

Clare: The dormitories are still there. At least they were in ‘74.

Vincent: I had a room right in one place that was reserved for visitors, scientists and so forth.

Sanger: Is that the hotel that you were talking about?

Clare: No.

Vincent: Just a dormitory.

Clare: Haven’t you ever been there?

Sanger: Yeah, but I don’t remember any dormitories in Richland. I thought they were all out at the camp.

Clare: No, they had fancy dormitories in Richland.

Vincent: That was where the clerical workers—

Clare: The bank was here, and their restaurant was here where the cafeteria was, and all of that area was full of two-story dormitories. They had hardwood floors and oh, they were fancy.

Vincent: We had to keep the people in. We had a trainload of people come in every day, and a trainload left because they just couldn’t take the weather. Every time the wind blew there, gravel about the size of the end of my finger would blow. It started at four o’clock every day. You could just depend on it. You could set your watch on it. The gale would start, and everything would just disappear.

Sanger: That’s what another guy said. At four o’clock at the camp the wind would come up, and about this much dust and sand came in.

Vincent: Yeah, my wife’s mother came to visit us. Her mother gave her hell because there was gravel and sand at every window. She cleaned it up with a vacuum cleaner, and it wore out every darn vacuum cleaner.

Clare: So my father was sitting by the table when I got home from work that night, or by the windows. He said, “Come on, look.” I felt so good!

Sanger: How did you two meet?

Vincent: She was in the office there, with the security people.

Clare: I went into the training center in May.

Sanger: May of?

Clare: May of ‘43. That was down in Georgia, Fort Oglethorpe.

Vincent: You were in the Army?

Clare: In the Army. I was in the WAAC at that time.

Sanger: What was that?

Clare: The Women’s Auxiliary Army Corps.

Sanger: What does that mean? What’s the difference between that and the Women’s Army Corps?

Clare: The Women’s Army Corps, you were in the Army. If you were in the Women’s Auxiliary, you were not in the Army.

Sanger: I see.

Clare: So then they put us over in the staging area in CCC [Civilian Conservation Corps] bunks and CCC barracks, and the whole bit. We waited, and we waited, and we waited, and we waited, because we didn’t know what was going to happen to us. There were two of us.

Sanger: That was in Georgia?

Clare: That was in Georgia. Then all of a sudden they said, “Get packed. You’re on such and such a train for New York.” We still didn’t know what we were going to do. They wanted us up in the Manhattan District, and they couldn’t get transportation for us. They were all set to fly us up, when they managed to get a train there. There was Lieutenant House, who was the head of the group, the Master Sergeant, and two other girls.

Sanger: What had you been doing, secretarial work or what?

Clare: That’s what I finally ended up doing. So we stayed up there and learned a little bit about Dewey Decimal, and how they did things. Chip stayed and the two girls, Devon and I, went down to Tennessee. We were the first three WACs down there.

Sanger: That would have been about what?

Clare: That was in August of 1943.

Sanger: You worked there?

Clare: We worked there in central files. We had the classified files.

Sanger: You were kind of working for the Corps of Engineers?

Clare: No, we were military and we worked for the Manhattan Engineering District. We stayed there, and then around the last of October, they were talking about the detachment that was coming out here, to Hanford. I wanted that detachment.

Sanger: Why was that?

Clare: Because it was close to home.

Sanger: Where are you from?

Clare: Here.

Sanger: From Portland?

Clare: Yeah. I wanted to work out here. I can work out here just as well as I can work back in Tennessee. They said, “No. You’re not on the list, and we can’t put you on the list.” I didn’t sign up to go down to be sworn into the regular Army, and I didn’t say anything.

Finally they called me into the office and I said, “I want to go in that detachment.”

They said, “I’m sorry.”

I said, “That’s great, then I just won’t sign up into the regular Army.” Guess where I ended up? There were six of us, plus Lieutenant [inaudible], that came out here. We were the only WACs out there for quite a while.

Sanger: Where did you go first at Hanford?

Clare: Actually, I lived right in Hanford for quite a while.

Sanger: At the big camp?

Clare: At the main construction camp.

Sanger: Yes, along the river there.

Clare: I don’t know if they’re still there, but they had those great big H-type barracks.

Sanger: No, there’s nothing there now.

Clare: They had them, single-story. Your laundry and bathrooms were in the cross of the “H.” The WAACs had one part of that.

Sanger: So you lived with another woman in this one room?

Clare: Oh no, we had the whole list. By that time, there’d been a lot more WACs brought in. After the first of the year, they brought a lot of WACs in. We had that. We stayed together. I don’t know about the men, but the WACs were not encouraged to have social contact with the ordinary people.

Sanger: The construction workers, you mean?

Clare: Yeah.

Sanger: Do you recall about how many WACs there were?

Clare: Oh, twenty-three.

Sanger: You were all doing more or less the same thing?

Clare: I don’t know. Most of the ones that I knew were either doing teletype or secretarial work. I don’t know what the girls that worked in the areas – I have no idea what kind of work they did, but I assume it was the same kind of secretarial work.

Sanger: What were you doing?

Clare: I was a secretary. I started out working in central files again. A gal in central files tried to do me in. It was a silly thing. I went on leave, which I had permission to do, leave at a certain time. She went down in the safe and stayed there. When I left, I went to the safe, and fortunately I had people that heard it. I told her, “I’m leaving now.”

She said that I left without telling her, and leaving all of the papers that were on the desk and in the safe unattended. They were all set to get me in trouble. I don’t know if she thought I was going to get court martialed or not. She really thought she had me.

Sanger: How old were you then?

Clare: I was about twenty-three.

Sanger: What’s your first name?

Clare: Do I have to tell you? My first name is Clarabel, but I go by the name of Clare.

Sanger: C-L-A-R-E?

Clare: A-B. Yes.

Sanger: That’s an old name, isn’t it.

Clare: Clarabel the cow!

Sanger: Two words.

Clare: No, just one word. C-L-A-R-A-B-E-L.

Vincent: That was just the time when the funnies had Clarabell the Clown. I mean, that’s why you were named that.

Clare: No! I was adopted, and my mother doesn’t know where my name came from, but for some strange reason, they kept the name that was on my birth certificate.

Sanger: Well, that’s normal, I suppose. Then how did you get together then?

Clare: After I had the trouble with this gal. I mean she was a nasty one. Nobody else could work with her either. They finally transferred her someplace else.

Anyway, the head of intelligence came to me and wanted to know, “I need a receptionist and somebody that could do typing and stuff for me. Will you do it?” I was tickled to death to get away: a new experience. So I just moved down to his office, and I worked down there.

Sanger: Which was in Richland?

Clare: No, still in Hanford, in the old military intelligence office in Hanford.

Sanger: At the camp.

Clare: I went to work then as a secretary for safeguarding military information. Bill, who was the head of it, wanted to have an office in Richland. He wanted one up in Hanford too. So I was the one that went down to Richland. I was the first WAC that went down there. Boy, did I get treated nice. All of those girls liked me so well. I worked in that office all the time, and it was quite a bit later before the gals moved from the Hanford camp down to Richland to work.

Sanger: So that’s when you met?

Clare: Yeah. We worked together in the same office, and in the same building in Richland. He was in Hanford too at the same office, and it just went on from there.

Vincent: We worked both places, and still nobody knew what I did. They were too scared to ask what the hell I was doing.

Clare: That’s the way a lot of them worked. I didn’t know what the other girls did, but it was something you just didn’t do. You didn’t ask anybody. It was just accepted that you didn’t ask anybody what they did.

Vincent: That was the training. That’s the office staff in central. The Colonel’s secretary was one of my girls.

Sanger: Where did you get your best information, besides from the hotel clerks and from some of the stenographers?

Vincent: They knew my telephone number. I got calls at all times of the night and day.

Sanger: What kind of a story would you tell them, when you would ask them to keep their eyes open?

Vincent: I told them they were working for the U.S. government. It was a highly classified thing, and you weren’t to tell anybody what they worked on, because it might get them killed. They had quite a story.

Sanger: They probably loved it.

Vincent: They did. I had two old ladies there that were in their sixties.

Clare: Don’t you call them old! [Laughter]

Vincent: They were dears, I’ll tell you that. They gave me some awfully good information. I would just ask them and they would check it out. They knew a lot of people.

Sanger: Did they work in the hotel?

Vincent: No, they were citizens. They had this little house just outside the borders of the place. They knew all of the other people there in town.

Sanger: So they had a network of their own.

Vincent: Sure. They belonged to every knitting society and blanket society. They were really busy. If they came across any little thing they thought they should mention, they told me.

Sanger: What might be an example of something they might hear that they would find suspicious?

Vincent: There was one thing. Nobody knew what we were doing.

Sanger: What was happening out there.

Vincent: One story that they picked up for me was that we were making rockets, anti-personnel rockets.

Sanger: So they passed that along to you and told you who had said that? What would you do about that? Then you would pursue it?

Vincent: I just sold it as, “This person is starting rumors, and it would be a good idea to keep track of him.” I told the office where I worked. They said OK, and they took care of it. The guy that had said that was quite a young fellow. He wasn’t married, so he got drafted real quick, and he ended up in the Army. [Laughter]

Sanger: Did you personally have an idea of what was going on out there?

Vincent: I knew all about it from the first.

Sanger: That’s so you could recognize—

Vincent: I was pretty shocked when I got in there. Oh, about a month, Charles Lamb and I [inaudible]. I thought the Major knew what I was there for. He called me into the back room, and Charlie Lamb, and said, “This is highly classified and I don’t want it to get out. We’re making an atom bomb.” Hell, I knew that a year ago!

Sanger: You learned that in Chicago?

Vincent: I learned that in Chicago when they interrogated me, because they wanted to know where I had gotten this information from Astounding Stories.

Sanger: Astounding Stories. Was that a magazine?

Vincent: Yeah. That was a scientific magazine.

Clare: It was a story-type magazine, wasn’t it?

Vincent: Yeah.

Clare: We used to take it all the time. There was another one that we used to take all the time called Analog.

Sanger: In other words, fiction?

Clare: Yeah.

Vincent: Science fiction, and it was these people that were actually making the damn thing that were writing.

Sanger: For fun?

Vincent: For fun and for money. You think those scientists made a lot of money? Forget it. The government paid them just like anybody else. I got my private’s pay, but I didn’t have a chance to spend it.

Sanger: Is that as far as you advanced?

Clare: Shall we tell him?

Vincent: Yeah, she and I got married, and intelligence all of a sudden found out my rank. They didn’t know whether I was a general or whatnot. I carried on like I was.