[To see an edited version of the interview published by S. L. Sanger in Working on the Bomb: An Oral History of WWII Hanford, Portland State University, 1995, click here.]

Clare Whitehead: I got raised to Tech Sergeant, so he immediately got raised to Tech Sergeant. He said, “Well, we figured it was too bad we did not get married earlier. We would have been generals by the time we retired.” [Laughter]

Stephen L. Sanger: Well, did you know what was going on out there at all?

Clare: I knew in this way. As far as I was in files, I didn’t, but there was a job that certain ones of us in the intelligence had to do. Each one was assigned so many periodicals and newspapers. We had to watch for the word. One of them was “atom.” There was a whole list of words and names that we had to watch for. I had never put it together as an atomic bomb, but I knew there was some kind of atomic device. But I heard nothing, no indoctrination, except we were—

Sanger: Did you sort of put two and two together?

Clare: Yeah, but we were just told, “We do not talk about things. We do not ask questions. We just do our work.” Well, then I got to the point of when a gal in one of the other offices went for her vacation. Then I had to make out a monthly report of where all of the top-secret papers were. I was only cleared for “Secret” and of course, it meant I had to write such and such a paper and where it was and such and such a paper. Well, I got a lot of information from that just by reading titles.

Vincent “Bud” Whitehead: That reminds me. I got a lot of information from the files. They made me in charge of headquarters. Everybody had to take their turn at answering the phone. It was a 24-hour service. I went through all of the files. Of course, they were all under lock, but I could pick all of the locks. [Laughter] So I picked the locks and I found out that they did not fancy me very much as an agent. [Laughter]

Sanger: Oh, is that right? You read your personnel records?

Bud: Oh, yeah.

Sanger: When did you get married?

Clare: Vincent was born in ’46 so it was in October of ’45.

Sanger: You were not married while the war was still going on?

Bud: Oh, yes.

Clare: Yeah, we were both still in the military.

Sanger: I mean married when the war was going on.

Clare: Yeah.

Sanger: Because it ended in September.

Clare: No, the war had ended, but I was still living in the WACs [Women Army Corps] dorm. Do you not remember that wild party we had that night? Did you not go?

Bud: Yeah, I went.

Clare: Oh, Lord, that was a shameful affair. [Laughter]

Sanger: In the WACs dorm, the women’s dorm?

Clare: Yeah.

Sanger: The women’s dorm?

Clare: It was no going off in the various bedrooms. It was just a wild drinking party, is all.

Sanger: Did that sort of thing go on quite a bit?

Clare: Oh no, uh-uh.

Bud: You did not. I was so damn busy, I did not even have time to scratch my back.

Clare: Oh, no.

Bud: It was a 24-hour job and they did not give a damn when I slept.

Clare: We were always encouraged to stay with the military intelligence crowd. I do not think there was anybody that partied with DuPont or anyplace else.

Sanger: In other words, there was not any crossing over.

Clare: No, they did not want it.

Bud: Every plan that was made there was called a matching strip. You knew what was in that area. The guy that was working on the sub-strip, he knew what you had done up to that matching. He made his connections there and then he did the rest. That is the way—the whole thing was that way. The need to know was the basis.

Sanger: You lived in the men’s dormitory in Richland then?

Bud: No, I stayed in the dormitory until I was given the safe house.

Sanger: Oh, I see. That was a regular house?

Bud: Yes.

Clare: Yeah. That is the house we lived in after we were married.

Sanger: Oh, it is? But you lived in the women’s dorm in Richland after you left the camp?

Clare: Yes.

Sanger: You stayed at Hanford for a while after the war, then?

Bud: No.

Clare: Yeah, because—

Bud: Because I was still in. She was out.

Clare: Let us see. I got my discharge in March ’46. You came up with your points in May.

Bud: Yeah, May 5 is when I got discharged, of ’46.

Sanger: You were still in Hanford then, both of you, when you were discharged?

Clare: Yeah.

Sanger: But you were married by then?

Clare: Yeah.

Bud: Yeah.

Sanger: Where did you go then?

Clare: We moved back and forth.

Sanger: Have you been here ever since?

Bud: I went back to work for the Corps of Engineers, but this time is not the same.

Sanger: You stayed with them?

Bud: I stayed with them until I retired.

Sanger: That is interesting, isn’t it, in a way. You were at the Corps before you were drafted?

Bud: Uh-hm.

Sanger: And then went to one of the big Corps of Engineers workplaces as a military intelligence person and then came back to the Corps afterwards.

Bud: Oh, I met a lot of people up there from the Portland district. They knew me as a surveyor down here because they could not figure out what the hell I was doing up there. [Laughter] They did not move across as many lines as I did. If they were a designer here, they went up there designing. The head of the motor pool.

Sanger: That is odd that they took the person who was a specialist at something and put him into something you knew nothing about, right. In the Army, that is.

Bud: Well, they figured—

Clare: A lot of it I think they wanted, don’t you?

Bud: Yes, I think that is what they were looking for. But the fact that I knew what they were doing, that had an awful lot to do with it.

Sanger: Oh, I see.

Bud: That had more weight than any rank or anything else you could have, the fact that I knew.

Sanger: They knew you knew because you mentioned reading those stories, etc.?

Bud: I knew the basic of what these fellows were talking about, see.

Sanger: Did you have quite a bit to do with [Colonel Franklin] Matthias or not?

Bud: Let us see. On my discharge, he wanted me to give the list of my informants.

Sanger: Oh, he did?

Bud: Yeah, and I told him, “No.” Those people trusted me and nobody else.

Sanger: How many people say at Hanford knew what exactly what you were doing? I mean there had to be.

Bud: Nobody.

Clare: Oh, nobody did. I did not even know.

Bud: I was married to her and she did not know.

Sanger: What did you think he did?

Clare: He was the photographer.

Bud: I do not know how I got pulled in. [Charles] Lamb was the photographer. He went to another base, and I do not know where. I forgot. I had to pick up his job, just another assignment.

Sanger: Did you ever actually take pictures?

Bud: Oh, yes.

Clare: Oh, yeah.

Bud: I used to take them for the—see, the state police were not allowed. The Washington State Police were not allowed on the project, only by invitation. I had to take their pictures for them.

Sanger: What, you mean accidents or what?

Bud: Accidents. I saw more blood and guts than any guy in the Army because of automobile accidents.

Sanger: You probably knew Robley Johnson, who was a DuPont photographer?

Bud: No, he and I never crossed.

Sanger: Oh, you did not. Well, he mostly I guess took photographs of DuPont projects.

Bud: Yeah, construction.

Sanger: Also the personnel photographs.

Bud: Well, I had to take care of the suicides and the murders and all of that. They held one man on the—I was down here visiting my folks for three days. They held him [inaudible]. He was a suicide. We had to prove that anybody that died on the project died the way they were supposed to and that it was not part of an espionage deal, you see.

Sanger: Oh, I see.

Bud: We had to prove it.

Sanger: That was part of your responsibility?

Bud: Right.

Sanger: Well, what, did everybody die the way they were supposed to have?

Bud: Yeah.

Sanger: Were there many homicides?

Bud: Well, I just came out to the corpses and took the pictures and made the notations of the weather and so forth and so on. I did not inquire whether they were.

Sanger: Nobody seems to know. I mean there were a lot of stories about knifings and so on.

Bud: Hanford, in the beer parlor there. We had knifings. We had a man every day who was dead with the knifing. A day did not pass. Oh, we had all kinds of other things. Like a girl was claiming she was raped. They asked her, of course. They wanted to know. I don’t know why I was at the police station at that time. She wanted to have this guy arrested because it was rape because she was not of age until after midnight. [Laughter]

Clare: I tell you, there was a bunch of weird people living up there.

Bud: Another time, I was pulled off my job. They wanted this guy arrested for putting something across the fence. On the outside.

Sanger: On the outside?

Bud: On the outside, and he tried to do it through a barbed wire fence.

Sanger: I think I have heard that.

Clare: I am not the nanny.

Bud: We had this gal that was in trouble with a lot of people. I do not know why I was there. I had nothing to do with the case. “I just had to have it,” she said.

The judge says, “Every day?”

“Oh, a lot of the time during the day, judge.”

He said, “Why so many times?”

She says, “I get a headache if I don’t get it.”

Sanger: Where was the judge?

Bud: He was down in Pasco.

Sanger: Oh that is where they took the—

Bud: Took the civilians.

Sanger: The criminals down there?

Clare: Well, she had done a guy in with a hot iron because he kept messing around and messing around. Then when she was injured, he lost interest.

Bud: That is another one. That wasn’t this gal.

Clare: Oh.

Sanger: Did those things happen on the project?

Bud: Yeah, on the project, but they were civilian cases and had nothing to do with the military. As soon as we passed them through, you see. It was a civil case. Everything was all lined out, you know: where, what, who, when, and why and so forth. You had to fall within a certain line of procedure.

Clare: Up in Hanford, it was really bad because they had all of these women barracks and they all had barbed wire fences around them, supposedly to protect the women. I do not know whether the men’s barracks had the same thing or not.

Bud: Yes, yes, we had the same thing.

Clare: Yet, here was wives in these barracks, men in these barracks. There was no place to socialize except that beer hall.

Bud: Do not forget the parking lot where they parked the buses. That is where most of them got together.

Clare: Honey, I was a young, innocent thing at that time. I did not know about those things. [Laughter]

Bud: I did.

Sanger: Another guy who worked – he was in food service – said that on weekends that guys would get drunk and go steal dump trucks and load the dump trucks up with women, beer, and mattresses and drive out in the desert. You ever hear that story?

Bud: Oh, yeah.

Clare: I never heard of that.

Sanger: Somebody else told me this. This woman, a physicist’s wife who was in North Carolina, she said that she apparently lived across the street from somebody she thought was in military intelligence. He was in plain clothes and was mysterious. She found out that he got his best information—I do not know how she knew this, but she said he got his best information from the brothels around Kennewick or Pasco. Does that sound plausible?

Bud: Yeah.

Clare: Well, I know who that was. [Laughter]

Sanger: But she said he was married, and he had a beautiful wife who always went with him on these trips.

Clare: Oh, no, that is not who I was thinking of then.

Sanger: That is not the same one?

Clare: That is somebody else. Well, I might know him, if she is good looking.

Bud: Yes, she was good looking.

Sanger: Some of the agents got information from prostitutes, I suppose?

Bud: Oh, yes, but the whole thing was I was not involved in the crime aspects. I was espionage.

Sanger: Anti-or what? That is what counterintelligence is I guess, espionage.

Bud: Espionage, period. My first mistake was I found the guy in Chicago and it was a criminal case. I got the balling out of my life. I was not to spend one doggone minute with crime. If I saw a hold up going on or a murder, I was not to pay any attention to it. I was espionage. “You have got enough espionage to keep you busy. You do not have to go around pumping up murders.”

Sanger: You said you were the only counterintelligence person at Hanford.

Bud: Right.

Sanger: But you had tentacles out?

Bud: I thought there was people watching me, and doing that because they were acting. I did not have any line on that. Of course, it was my job to find out who they were and what they were doing.

Sanger: How old were you when you were out there?

Bud: I was in my thirties.

Sanger: At Hanford?

Bud: At Hanford, yes.

Sanger: Your early thirties?

Bud: I was ten years off of the date and you have got my birth and my age.

Sanger: You are 75, oh, I see, okay. Oh, you are 76.

Clare: He will be 76 in November.

Sanger: How old are you?

Clare: I am nine years younger. No, I am seven years younger than he is. I did tell you.

Sanger: Seventy or seven?

Clare: I am seven years younger than he is.

Sanger: Okay.

Clare: Six and a half to be exact.

Sanger: Sixty—so you are 69?

Clare: I will be 69 in July.

Bud: I was robbing the cradle.

Clare: No, I was “Whitey’s child bride.” That is what they called me up at work. I was Whitey’s child bride.

Sanger: That is not really an incredible amount younger, I would say.

Clare: Oh, no. I was—

Bud: Her friends thought so.

Clare: I was one of the two cases of polio they had ever had in Hanford.

Sanger: Oh, you were? You survived, I see. Any ill effects?

Clare: I still have to wear braces from time to time. I have been down and out for about five years. I have a feeling I am going to have to go back to them.

Sanger: When would that have been?

Clare: Oh, shoot, before we were married. We were married about October, because he had asked me to marry him and I told him no. Because at that point I did not know whether I was going to be full of vim and vigor, vinegar, or whether I was going to still be in trouble.

Sanger: How long were you ill?

Clare: I was in the hospital for two weeks. I was on leave for two weeks. I did not go back to work. I never did go back to work full time, did I?

Bud: No.

Sanger: People forget what a big thing polio was.

Clare: The medical officer that we had out there, I am surprised he did not kill everybody that was there because he did not know medicine for the birds. I went to him sick two or three times before I finally became acutely ill. All he would say was, “Oh, you have got muscle problems,” or “You pulled a muscle,” or something of that sort.

I was very fortunate. Finally, one night I became acutely ill and they took me in to the hospital. They did all kinds of tests. Then, the next day, all the DuPont doctors came in. There must have been four or five. They had as one of their doctors an epidemiologist from Montreal. He worked there. That was his field.

Bud: There were ton of Canadians. He was Canadian.

Clare: Then I had a private nurse days. I did not have a private nurse at nights, but days I had a private nurse. It was just about the time that Sister [Elizabeth] Kenny came out with her findings. Boy, I tell you, I spent hours all day long with those hot packs on that I thought was going to kill me off, but they helped so much.

Sanger: You are talking about the Army doctor?

Clare: Yeah.

Bud: Yeah, it did not matter how good or how bad the Army doctor was. That is the doctor we went to.

Clare: Oh yeah, you had no choice. But he had a little kid. That boy was 18 months old. He had taught himself to read.

Sanger: Oh, he did?

Clare: He had taught himself to use a typewriter.

Sanger: He was the doctor’s son?

Clare: He was the son.

Sanger: What was his name, do you remember?

Clare: The son?

Sanger: The doctor.

Clare: [Inaudible] Max Dubin. As a doctor, I mean I probably would not have been here today if it had not been for the DuPont doctor.

Sanger: They were a higher order, were they?

Bud: Oh, they were.

Clare: Far, far higher and more experience. He would come in to see me every day. He said, “Well, what did your doctor tell you to do today?”

I would say, “Well, this and this and this.”

He said, “Yeah, that is exactly what I told him to do.”

But the other man was a DuPont man and he died. They did thorough studies after that to see if they could find a spot where we had been at the same place, or had eaten at the same place, or had been in the same party or something. Never had we ever crossed. We were the only two cases.

Sanger: Oh, is that right?

Bud: He was sent away in a lead casket. That is what I could not understand, but they told me they were afraid of an epidemic. Of course, polio in those days was a scary thing.

Sanger: You still know any people who were out there when you were, during that period?

Clare: Johnny Gaughan and his wife were up here about two years ago. We still get Christmas cards from Bill and Hazel Eisenhart.

Sanger: What did they do?

Bud: He was head of security.

Clare: Safeguarding military information.

Bud: Yeah.

Sanger: He was in the Army?

Clare: Yeah.

Bud: He was in the Army. He was a lieutenant.

Sanger: Where does he live?

Clare: He lives in York, Pennsylvania. Then [inaudible], shoot, I thought his address was around here someplace. He is just remarried. He lives down in Florida.

Sanger: What did he do?

Bud: He was an agent.

Clare: He was an agent, but he worked with us. I do not know if that was his total job.

Sanger: But he was not espionage?

Bud: No.

Clare: No, he was just an agent.

Sanger: What did they call that, just military?

Bud: Security agents.

Sanger: Military security or what?

Bud: Military security. That was the highest, see. There was the MPs below them. Below the MPs were the DuPont people. Anybody that came in privately had to go through all of that.

Sanger: Well, DuPont had more or less their own civilian force?

Bud: Oh, yes.

Sanger: They were called what, just DuPont security?

Bud: DuPont security.

Clare: I am just trying to think. Gosh, I cannot remember.

Sanger: Do you remember a guy named McHale, Francis McHale?

Clare: Oh, Mac McHale, I was trying to think of his name, sure. He was still up in Richland last I knew.

Sanger: Yeah, I talked to him. I do not know how I ever found him, but he was a DuPont security worker.

Clare: Yeah, yeah, he was DuPont security, but he married a WAC.

Sanger: Oh, he did.

Clare: I think he is divorced though now.

Sanger: I did not ever see him. I talked to him on the phone.

Clare: Don’t you remember when we were there? We tried to call him and he was gone.

Bud: Always away.

Clare: Well, we were only there that one night and we could not get a hold of him, yeah.

Bud: There were several we tried to call who left.

Clare: Well, so many people have. There were two men that used to live here. I do not know whether they still are here or not.

Sanger: In Portland?

Clare: In Portland. Mike McClenahan. He was in a law office in [inaudible].

Sanger: It seems like I have heard of him. What was his last name?

Bud: McClenahan.

Clare: McClenahan.

Sanger: M-C-C-L—McClenahan, probably A-H-A-N. Mike, where is he, do you know?

Bud: He is in [inaudible] right now. He belongs to a bunch of lawyers there. He got in there.

Clare: You saw him before you retired in the barbershop, was it not? I was trying to think. Johnny Hull lived here in Portland for a long time.

Sanger: What did he do?

Bud: Both McClenahan and he took shipments and took them to [New] Mexico.

Sanger: There was a guy, maybe you knew him, [O.R.] Simpson.

Clare: “Big” Simpson?

Sanger: Yeah.

Clare: Yeah, is he still alive?

Sanger: Yeah. Well, he was last year.

Clare: Well, did you go to his house by any chance?

Sanger: Yeah.

Clare: Did you see his boy?

Sanger: No.

Clare: Oh, shoot. I would like to know what he looked—does he live nearby?

Sanger: I do not know, but Simpson lives along the levee, along the river in Richland.

Clare: In Richland?

Sanger: It is a nice house. He apparently loves and enjoys life. Some buddy of his, a sergeant, hangs out with him.

Clare: McClenahan was his pal up there, was he not?

Sanger: Oh, he was? Simpson was good because he said he was the lieutenant in charge of at least one of the groups that took his convoys when they would take a convoy up to Fort Douglas, Salt Lake City. Then they would transfer the plutonium. They would get out of the car, somebody from Los Alamos would get in, and they would go the rest of the way.

Clare: You know, this is not of any interest to you as far as your book is concerned, but my cousin was a physicist down at Y and I did not know it.

Sanger: Oh, was he? What was his name?

Clare: Danny Grim.

Sanger: Grim?

Clare: Grim. I think it was spelled G-R-I-M.

Sanger: And you did not know that?

Clare: No, I did not know that until well after the war was over. I was trying to think. I cannot think of anybody else.

Sanger: Well, I was down there.

Clare: I cannot think of anybody else. Now, there was Bill. We know he is in York. Cloy is down in Florida. Johnny Hull, I do not know whether he is still here or not. The last I heard, wasn’t he running a tavern out in [inaudible]?

Bud: For a little while.

Clare: But I do not know where he is now.

Sanger: Was he in military intelligence, too?

Bud: No, he was on the delivery desk.

Sanger: Yeah, that was an interesting part of it, too.

Clare: Tommy Every, I do not know where he is. He is a Portland boy, but I do not know whether he came back to Portland or not.

Sanger: I suppose you kept some friends for some time after the war.

Clare: Yeah, we did for a while and then there was–

Bud: You know somebody you forget for Christmas, or something came up that they were sick or something. Then you never even noticed. They just dropped off that way. I know I can understand that because I got sick with this breathing business and this arthritis. I lost interest.

Sanger: Did you have children?

Bud: Yeah. Three: two girls, one boy.

Sanger: But they were not born over there, or was one of them?

Bud: No.

Clare: No, we moved down to Portland in May, before the boy was born in August.

Bud: I did not want him born on the project.

Sanger: Why not?

Bud: It was awful. I had the inspection every damn month with x-rays. They did not know a damn thing about what the effects of radiation were. The only thing that they had, they used to have that stuff that—

Sanger: Radium.

Bud: Yeah.

Sanger: To make it shine in the dark?

Bud: Yeah. They knew the effect of that, but the girls that did that were right in contact with it. Here, they had no contact. They really did not know too much.

Clare: Well, that is the trouble with his lung problems now. The doctor cannot find a reason for it.

Sanger: Oh, they cannot?

Clare: I mean it just is there.

Sanger: When did that start?

Bud: I do not know, maybe it just crept in.

Clare: Well, it became acute two years ago, January. That is when it got to the point where—well, I do not know. He says he was having breathing difficulties for a long time before that, but that was the time when he was in the hospital. The doctors began investigating to see what the trouble was. He is going to one of the best lung specialists here in Portland, and they still cannot figure out what the problem is.

Sanger: It is not emphysema?

Bud: No.

Clare: No, it is not emphysema.

Sanger: No?

Bud: They do not know. They actually came out and told me they do not know. I had an experience like that before. I was a patient of Dr. Scott and I had tumors that were attached to the body lining. They were as big as grapefruit. Finally, there was enough of them that it crowded the heart. He called in a bunch of experts there. They had the lights out and all my x-rays all around there. One of the doctors, he sort of grabbed me. He says, “Now look, you can see right there. You have got a hold of the patient!” He dropped me like a hot brick. [Laughter]

Clare: But we have always wondered if that is where it came from.

Sanger: What happened to those? Did they operate or what?

Clare: No, they disappeared.

Sanger: They did?

Clare: Yeah, the way they came.

Bud: All they did was they left a mark where each one was, you know [inaudible]. It was like a grapefruit. It had a little stem and then a big thing like this.

Sanger: Really, and then it just went away and disappeared?

Bud: Dr. Scott questioned these different doctors about what the procedure should be. Some would have opened me up like a fish, you know, taking them out like you would out of a fish.

He says, “You cannot prove that that has ever been done. That would not be a cure. It might just set the whole thing afire. I am going to tell my patient that we will just keep track of it for a year by x-rays. We will x-ray every week.”

Clare: Well, the doctors all said, “Well, he is in the hospital, is he not?”

Bud: Yeah, I was down there listening to them.

Clare: He says, “No, he has been working every day.”

Sanger: Well, you do not suppose you got too many x-rays or something, do you?

Bud: I do not know. I had them up there in Richland.

Sanger: You did?

Bud: Yeah, because I was all over that project. I was getting more than—

Sanger: They wanted to check radiation?

Bud: Yeah. There were also reports of spies. We had found that somebody had taken a shit, right in the middle of one of the galleries of the plant.

Sanger: Oh, which plant? The separation plant?

Bud: No, it was where they were reducing the ore down. We had to explain that, of course. I could not explain it. I took a picture of it, but I could not explain it.

Clare: Cloy did that.

Bud: Cloy had to write the report and was carrying on.

Clare: Cloy was marvelous with words.

Bud: He just delighted in words.

Clare: He could just – we had one case.

Bud: He was an ex-lawyer.

Clare: Oh, he was called. I guess he was agent in line or something. He had to go clear across the river because there was a spy over there carrying a suitcase. They had better get over there fast. He went tearing over across the river. We wrote up a report about the cow carrying a suitcase. [Laughter]

Bud: He had more fun with them. There were certain types.

Clare: There was another one. I cannot remember what subject we made of it. Anyway, a racing pigeon had tired and it had come down in Yakima. He had to rush over there and solve that.

Sanger: To make sure it was not carrying a message or something?

Clare: We had some fancy little story about that.

Bud: We had more fun with those darn fool reports.

Sanger: Whatever happened to the case you were talking about? Did they ever catch the guy?

Bud: No. One of those secrets.

Sanger: Do you recall much racial problems with black and white?

Bud: No, no. The only time I ran into it was down in Tennessee. I had just come from going through a project area that was fenced. It had its own fence. I caught the bus. One-half the bus was Negroes and one-half of the bus was white, right down the middle of the damn bus. Each side had eyes out. They were just looking at and swearing at each other and everything. The bus driver saw me in my uniform. He says, “Thank God, can you keep it?”

I said, “Go right down to the entrance and we’ll shed these guys and their knives.” I stood up there in front. One guy unarmed. All I had was a uniform.

Sanger: That was enough?

Bud: That was enough. They did not want to mess with the Army.

Sanger: Incidentally, when you were in plain clothes in Hanford, I suppose you were armed then?

Bud: Oh, yes.

Sanger: With what, a handgun?

Bud: Yes, a Detective’s Special. I would rather have a brick.

Clare: You went on our vacation with that darn thing.

Sanger: A .38, huh?

Bud: Uh-huh.

Sanger: A small one?

Bud: Barrel this long.

Sanger: Two-inch barrel?

Bud: I had—

Sanger: But you had access, I guess, to a tommy gun.

Bud: Oh, in my car there was a rifle, a tommy gun, and a gas gun. I was a walking arsenal.

Sanger: Riot gun or not?

Bud: No, I did not have a riot gun.

Sanger: I guess you did not have to worry about a riot.

Bud: I had one of those officer’s rifles, what do they call those damn things. They are about as useful as a—

Sanger: Oh, a carbine?

Bud: Yeah, they are about as useless as my little Detective’s Special. You know, they sent me up chasing those damn balloons as espionage.

Sanger: I was going to ask you about that. What is the story on that?

Bud: Well, the Japanese manufactured a piece of paper that was out of this world.

Sanger: Those fire balloons?

Bud: Yes.

Sanger: Explosive or whatever?

Bud: Yeah. They attached a fireball to them. It had fins and all fanciness. Then they had an explosive in there to blow up the balloon, because they did not want anybody to know what the hell it was. Here, out of the sky came this thing and set everything on fire. It was ingenious.

It had a little ring in there. It had holes drilled in it that had firecrackers in them. Now, the firecrackers would blow up a little sandbag, see. That would lighten up and the balloon would go up. It would go up from there and it would go along. Then all of a sudden, it would start sinking because it rained or got moisture on it and it started sinking. Well, as soon as it hit a certain altitude, one of those firecrackers would go off and back up it would go. We found those things clear over in Wisconsin.

Clare: I had a piece of the paper for a long time. It is around here still somewhere.

Sanger: From one of them?

Bud: Uh-hm. They had me up in this plane. We were up here. The damn balloon was down here. We get down there and the balloon was up there. That is what we kept doing all day long, chasing that damn balloon.

Sanger: How far did you go?

Bud: Well, I was chasing this one. I was just outside the district, just about a mile and a half away from the fence. I do not know, but fancy I flew that every morning. I finally got it. I threw a brick at it. I put a hole in it and it went down. I got out there and I start tromping all over that thing and got all the gas out of it. I radioed in that I had found it and got it. They sent a bus up with all of this specially trained personnel, gloves, full contamination suits, masks. I had been walking around on that stuff and they had not told me! They were afraid of bacterial warfare.

Sanger: Oh, how big was it, do you remember?

Bud: Well, I would say it was a little bigger than our living room.

Clare: You mean longer or bigger around?

Bud: Bigger around.

Sanger: Well, it had a bomb on it, did it?

Bud: Yeah.

Sanger: But it did not go off, I take it.

Bud: No, it did not go off. The explosive did not go off either.

Sanger: I understand that a couple came down on the project during that period. Did you ever see any of those that just on their own came down?

Bud: No, it was just this one. Two of them came down near Astoria. That is when the people were killed.

Sanger: There is a book about those. A friend of mine is interested in the subject. The Smithsonian put out kind of a long pamphlet about them, which details where every single one of them was found. You said you flew that fence line every day?

Bud: Yeah, that was one of my duties.

Sanger: Somebody, Army, a small plane, or what?

Bud: This guy had been over in Europe and he got wounded. He lost an eye. We had a little plane, an artillery spotter plane. He had it fitted with the MVPH slots [inaudible]. Then he had the air brakes on.

Sanger: So he could fly slowly?

Bud: Yeah, so he could fly slowly. Hell, if there was a wind blowing, he had trouble trying to keep that thing balanced. He would either go ahead or he would back up.

But he died. I used to fly with him every morning.

Sanger: You would, what? Check the perimeter? Is that it?

Bud: Check the fence, yeah.

Sanger: All the way around?

Bud: All the way around.

Sanger: That was quite—how long would that take?

Bud: Oh about an hour and a half.

Sanger: Would it? Then you were looking for what? Breaks in the fence or suspicious people?

Bud: What we were looking for was tracks of any kind from the fence or to the fence.

Sanger: It was smoothed or what so you could tell? Kind of like the Berlin Wall?

Bud: Yeah. That was done in Africa. The British had been using that for about 100 years.

Sanger: That technique?

Bud: That technique

Sanger: There was smooth what, sand or something on each side of the fence?

Bud: Yeah, well the soil there is sandy, you see. All it is is sagebrush.

Sanger: You would look for tracks. Did you ever find any?

Bud: No, I had to go out on one deal. There was a house, but they had run the people out. They were reporting people from in the project were going there, and they did not know what was going on. So I was sent out there to look.

Clare: Didn’t you have told them on the phone what was going on?

Sanger: That house was inside the fence?

Bud: Yeah. Anyway, I went out there. I had a driver, a young kid. We were perched up on the hill. I looked down. I said, “That’s the house. I want to go there.” The road led down this way and we followed it down the grade, you know. The damn kid turned the thing there and we went down. I spent all there praying and holding onto that damn set of blankets and the seat there to keep from popping off of it. My eyes were bugged out. I thought they had shoved my glasses off.

Sanger: In a Jeep or a car?

Bud: Jeep.

Clare: What was the name of the town that was up from Hanford? It was White something.

Sanger: White Bluffs.

Clare: White Bluffs.

Bud: White Bluffs, yeah.

Clare: Has anybody ever told you about the milkshakes up at White Bluffs?

Sanger: No.

Clare: Oh, it was just a little – I do not know if there was a little drug store or what. It was just a little building. These people were still there. They had not been moved out yet. The officer of the day used to stop down at the WACs barracks when they had to go up to White Bluffs. They would take two or three of us up and take us out for milkshakes. I have never tasted a milkshake like those milkshakes up there.

Bud: It was about 115 in the shade when they got the milkshakes. They thought they were in heaven.

Clare: Oh, it was pig heaven.

Sanger: Was that fairly early in the game that they were still there, or what?

Bud: The construction was still going on.

Clare: Oh, I do not know.

Bud: The thing was hurry, hurry, hurry. Everything, you know. Around the clock operations.

Clare: I was out of a lot of stuff because I lived down at Richland.

Sanger: Oh, yeah. Well, what was going in that house you were talking about?

Bud: I went in the house and I could not see that anything was going on. There was no empty beer bottles. There was nothing. There was just a torn up magazine in there. I take it somebody had to go to the bathroom was all I could tell you.

Then another thing. Boy, this was a definite deal to stop the project and everything. On your electric motors, there are ventilation holes all through the framework so the air can get in and get cooling air so the doggone thing will not overheat. Somebody conceived the idea –it was one of the men that had to do to keep the safety of the people. He had frameworks with wires on it so it was a mesh. He had that all in there. The guy that drilled the holes or the things to hold them on, he just drilled away and the damn motor was running all the time. Here was pilings come from the drilling there on the base of it. Somebody said [inaudible] there. It was just somebody’s dumb-headedness!

Sanger: Somebody thought it was sabotage?

Bud: Yeah, that is all they yelled, was sabotage.

Sanger: Did you ever find anything that really did look suspicious, genuinely suspicious that it might be sabotage?

Bud: No. Everybody was scared to death. By the time they got through with DuPont and our people, and we had security. The security men had to show a movie every month. Each area had to have this movie, a security movie.

Clare: That is something else that you and Johnny did.

Bud: Yeah, I had to take that over, too.

Sanger: What was the movie?

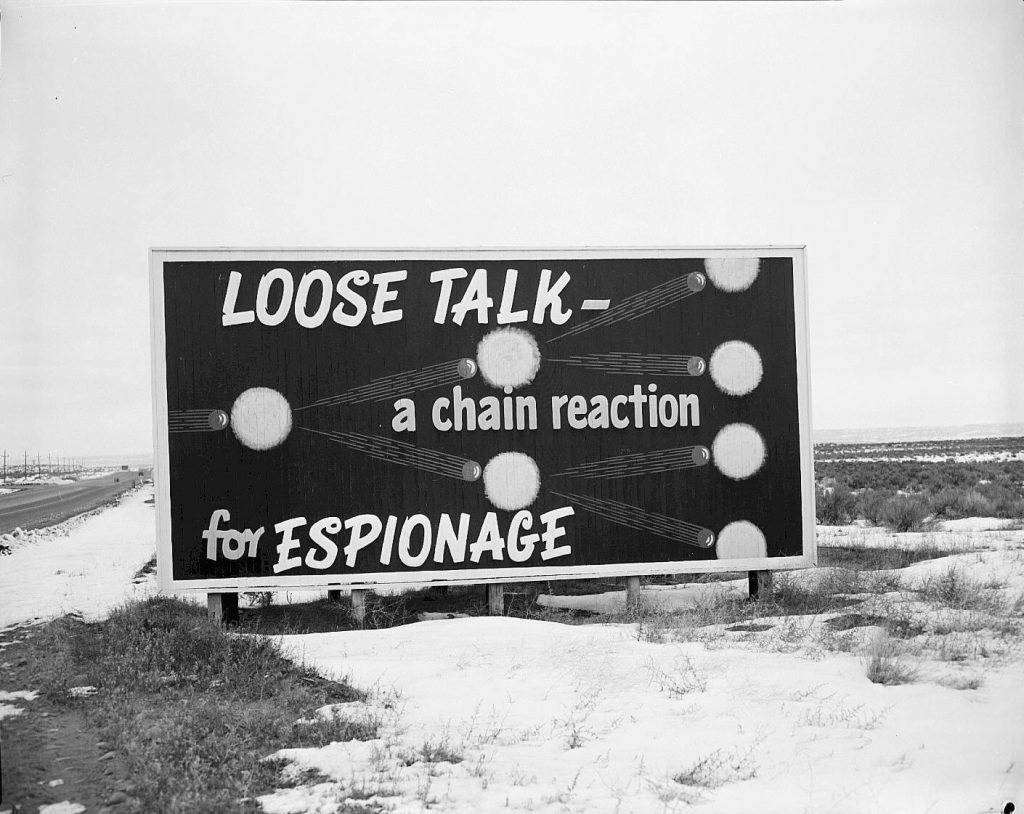

Bud: Old English movies mostly that showed how somebody with loose lips would flap out information and the submarines sink you.

Sanger: They showed those to the workers?

Bud: Yes. People, if you went up and asked their name, they would take a good look at you. [Laughter]

Clare: You know, we never saw any of those films.

Bud: I know. I often wondered about that. I was busy enough. I did not have to have any more.

Clare: In fact, I have never figured how I got in that project to start with.

Bud: I never figured out how I got in intelligence!