William Downey: Now, as I remarked, one of the security officers told me a little time before, there was going to be a really fantastic new thing, only one of the greatest things that ever happened in the history of the world. This kind of hyperbole I never took too seriously anyway.

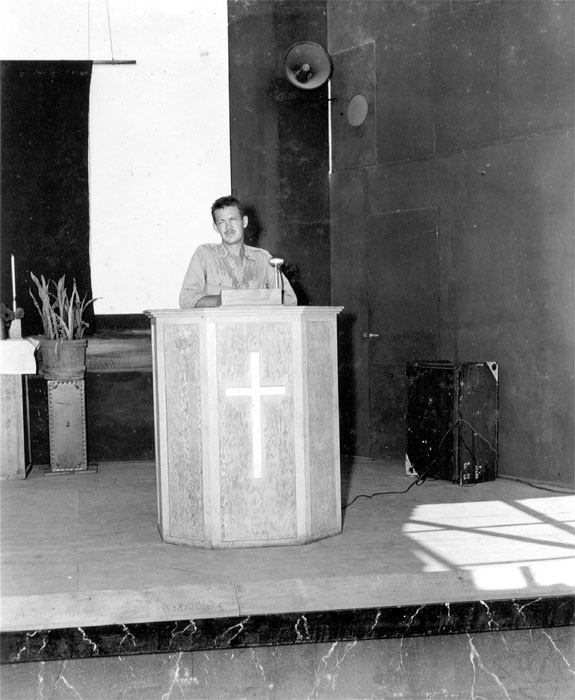

The night of the mission, there was a general briefing in one of the Quonset huts, and when all the data, all the information had been given in this general briefing, there had been special briefings during the day. They called it a general briefing and it was the custom of the 509th that the last thing on this was a prayer by the chaplain, which is me.

[Fr. George] Zabelka wasn’t even there. This is the night of the mission, he was not in the Quonset hut. I prayed this short prayer, which has been printed many times now. You can read it in the Dawn Over Zero. I have been really criticized for this by left-wing people, anti-bomb people. As I reread the prayer over and over through the years, I can’t see a doggone thing they are unhappy about. They certainly can’t complain about trying to end the war with it and end it in [inaudible]. They can’t complain about that. They can’t complain about my petition that God take care of our flyers, or would they rather a parachute—rather have me say, “Strike these bastards down.” I don’t understand these people.

The night they left, this was a lot of lights, you know, Hollywood kind of lights and cameras and so forth. Now that because Leslie Groves wanted the publicity and so forth, when they returned it was something else, a heck of a lot of people there. I was there again. A lot of flag officers or general officers were there.

[Paul] Tibbets got out of the airplane first and he was smoking a pipe. Saturday Evening Post back then had a big picture of it that’s been reprinted many times. He stuck his pipe up in his sleeve, he stood at attention, see. If you looked at that picture carefully, you could see that he was holding a pipe up there. General Spaatz, he was a four-star general, pinned the Distinguished Service Cross on his flying suit. This was the second highest decoration our country can give, and it’s for exceptional valor and that sort.

The Nagasaki mission almost was a tragedy. What I’m going to tell you about it has all been printed in books and so forth. They found out one of the gasoline pumps from one of the tanks wasn’t working, so they took off with 600 unavailable gallons of gasoline. [Charles] Sweeney’s point of view was that if they were short of gas they could stop at Iwo Jima and get re-gassed.

There were weather planes sent ahead to radio back on both of these missions, radio back the conditions of the weather. Because this bomb was not to be dropped by this elementary and primitive radar, but only by this Norden bombsight, which is extremely accurate. Japan was closed in with clouds, might have been like out there today. At 30,000 feet, visual bombing was not a possibility. Early in the morning, around nine o’clock, many, many times, many, many days, the clouds would be sparse and scattered. These two other planes were to radio back the weather conditions, the cloud cover.

Now, it happened that Claude Eatherly’s airplane had Hiroshima as the city about which he would radio back the weather. I think it was two-tenths cloud cover, and that was adequate for visual bombing. That was the Hiroshima strike. I don’t know who did it for the Nagasaki strike.

In addition to this, with these weather planes, there was two more airplanes filled with scientific equipment and people. Interesting thing, there was a very famous British air officer by the name of—a group captain, that’s the same as a colonel in the US Army. Captain Cheshire, I don’t know if you’ve run across his name.

Paul Filipkowski: Leonard Cheshire?

Downey: Hmm?

Filipkowski: Leonard Cheshire.

Downey: Leonard, right, right. He was the British pilot that led the Ruhr Valley Dam mission to blow up the Ruhr Valley Dam and cut the river free. He led that. [Prime Minister Winston] Churchill had called him in. I talked to him, you know, and he was a little provoked, because he could not fly, no room for him on the first strike. He had to wait for the second one. Churchill had called him in and made him, Cheshire, his—Churchill’s—personal representative. But he got on the second one.

So there were observers and this sort of thing and photographers and newspaper man, or men, I don’t know. They had another plane full of scientific measuring equipment. They were to rendezvous at a certain point on the way up.

Tibbets told me that he had told Sweeney, “You make one pass around that rendezvous and if they’re not there, go on to the target selected.” For whatever reason, Sweeney circled and circled and circled a little bit the rendezvous point, waiting for these other airplanes to get together, and one never did get there. They never joined up. Finally, he took off.

Because of this delay, the primary target—I believe it was Kokura—because of this delay, the weather had changed since the weather plane had reported and now it was socked.

They made three passes over. They could not see the aiming point. They saw an athletic field that was very close to the aiming point, but the bombardier, [Kermit] Beahan, would not drop that on anything but the aiming point. Away they had to go. Now, they’re realizing, after all this fiddling around, they’re low on gasoline. They got the damn bomb in there, and what to do?

They decided to fly to Iwo, I guess, and go over Hiroshima [misspoke: Nagasaki], the secondary target. And, when they got to Hiroshima [misspoke: Nagasaki], it was all socked in, too. But at the last moment, Beahan saw a big opening in the clouds—he was the bombardier—and away they went and popped her out there, missing the aiming point by about ten miles. But it exploded over a Mitsubishi factory, and all those Mitsubishi people were all fine little Japanese people who blessed us with the Jap Zero, as an example. And now are blessing us with their automobiles.

Filipkowski: Cars and trucks.

Downey: Yeah, some blessing. In any event, they took on off and landed on Iwo, and on the runway one of the engines quit altogether. This is all really true.

Well, the second mission was almost a tragedy, and it certainly could not be called a conspicuous success. No one would talk about that stuff at the time, see. But it’s all been written in books since.

You ought to read Paul Tibbets’ own story. Do you have that one?

Filipkowski: Right, I’ve got that one, too.

Downey: He discusses this in that book, about the same as I’m discussing it now.

Well, it was all great days. We were successful, and Japan’s still not, would not, still would not surrender under Potsdam. The point being, they wanted to preserve to preserve the Emperor’s status and not unconditional surrender. The Twentieth Air Force flew a maximum effort, one last maximum effort mission over Japan. I supposed if we had another atom bomb, a nuclear device, we would have used it again. But we didn’t have anymore. There wasn’t anymore. The first one was a uranium bomb and the second one was a plutonium bomb.

Filipkowski: I think the next one was around uranium, in weeks or something.

Downey: I don’t know. We just didn’t have one. A couple of days after that, Japan sued for peace under Potsdam, and the whole thing was over.

In my view, there’s very little difference between killing a Jap soldier in the jungles of Burma with a rifle bullet, and between that and killing Hiroshima off, see. It’s just a matter of quantity, not of quality.

This business of war is an evil, terrible thing. With the same forces of dehumanization and commitment to destroy, kill and destroy is everywhere. This is the terror and the horror and the evil of war. It’s everywhere involved, whether you just squeeze off one and kill a Jap soldier, or squeeze off a nuclear device. You got to remember this, we killed more on some of those incendiary raids than we ever did in Hiroshima. Nobody seems to get uptight about that.

Filipkowski: I know.

Downey: What we did in Hamburg, for instance, was just an unbelievable conflagration. I have read that the flames were so intense that it sucked in the surrounding air to feed the flames, causing wind that could even suck people into it. Beautiful Dresden, declared an open city, we just bombed the hell out of Dresden.

Now, nobody I know of with any loud voice has condemned these things, although the atom bomb is always a target for condemnation. It seems as if the Nazi, in the view of these critics, seems that the Nazi deserved worse treatment than the Jap. The point is, we had a device now, a device that the Soviets didn’t have. The Soviet sympathizers, well, in World War II there were a lot of them, because they were “allies.” Delighted to criticize nuclear strikes, and the Soviets didn’t have them.

In any event, in my view, the nuclear strikes were not substantially different in quality than the other part of the war. The napalm and the incinerator raiding of Tokyo and Yokohama, as an example, where all kinds of civilians were consumed.

One of the most critical things about it is we were going to invade Japan. In any event, we were going to invade. It was laid on. [George C.] Marshall expected something in excess of a million American casualties. It was going to one in that November, and then after the first of the year there will be a second invasion, higher up on the archipelago. There wasn’t an infantry man in the Pacific who wasn’t damn happy that bomb was dropped.

Filipkowski: There’s one I work with.

Downey: Huh?

Filipkowski: There’s one I work with. He was on a ship off Okinawa when the bomb went off.

Downey: He was happy?

Filipkowski: He was.

Downey: He didn’t want to hit that beach. I mean, here were these Japs, they had four million soldiers. Approximately two million from Manchuria, who had been blooded, who had seen some sort of action, and two million of them that were in reserve in the archipelago itself. Besides that, they were teaching children how to have hand grenades for these GIs that loved children so much. Women were being trained to run out in motor boats. This sort of thing that has a big explosive charge in the prow, forward part, to ram this against American vessels in the invasion.

This was going to be one of the bloodiest things in the history of the world. It’s not unreasonable to suppose there would be three million or more Japanese casualties.

Now, these people today who criticize this, they’re getting a damn cheap ride, eh. It’s very easy from this point to complain and criticize and exercise judgment upon what happened forty-plus years ago. They weren’t there, their posterior was not exposed, their ass was not on the line, they didn’t have to hear shots fired in anger, and they didn’t have to risk their life on an invasion, eh. So, why not be a smartass and criticize, eh?

Filipkowski: They always sound like there wasn’t a war on.

Downey: Yeah. Well, it’s just unbelievable. You see, the Jap was a barbarian. They like to think that they’re the cultured people of the world, and all that manure. He was a barbarian. Look what they did at the Bataan Death March, look what they did all over Asia, in an exercise of cruelty and inhumanity.

Now, I don’t get too excited about Pearl Harbor. This was a military strike against a military target. But look what they did to those GIs who had surrendered on Bataan, and that horrible death march that took place. It happened all over the Pacific. They were a bunch of ghouls.

I’m sure the point of view I had was a point of view that almost everybody had, namely, “Let’s lick these guys, change their situation, and then we all can go home again. Most of us go home again alive, not in a rubber sack.” Well, that expresses my view, pretty much, of it.

I’m very defensive of the nuclear posture of America today. I don’t go around again it. Here are these asses over there in Cape Canaveral bitching about the Trident. It’s MIRVed with ten warheads and they call it “a destabilizing weapon.” That means that we will get an advantage over the Soviets in such a way as to get them all upset and they may pull off a preemptory strike or this sort of thing, a destabilizing weapon.

But these people don’t say that the Soviets have at least 308 SS-18s, and if you don’t know what an SS-18 is you got no business talking about this subject. An SS-18 is a gigantic missile—ten warheads in silo, ready to go. The last number I read a couple of years ago is 308 of them. I don’t hear them talking about that SS-18 being a destabilizing weapon, eh. They’re always so neutral in favor of Russia.

Well, we haven’t had a major war since the close of World War II. I’m persuaded that what’s happening in Afghanistan, what has been happening there for seven years would have been what would have happened on a much larger scale in Central Europe, except our possession of the atom, eh, and this constant threat of annihilation.

If one observes the Soviet treatment of Czechoslovakia, oh, first Hungary and Czechoslovakia, East Germany and Poland, one could say they’re really pretty bad, they’re really pretty terrible. But after all, that’s behind the Iron Curtain and they’re just keeping things steady and on even keel and so on. You can’t possibly say that about Afghanistan, not at all. Here’s deliberate, cold, mean, tough invasion. I do believe that this would’ve been the story of Europe, except for our possession of the atom, the bombs.

Now, this is the reason I think these people are stupid, stupid. They invite the destruction of America and consequent destruction of the world. If America falls, forget it. The lights are out everywhere. The Soviets are going to rule. Anyone who doesn’t think the Soviets intend to rule simply entertains a skewed mindset that is beyond my understanding. It’s basic to the communist philosophy, and this dialectic is basic, that history is inevitably on their side, and nothing anybody really can do will prevent the ultimate success of the Soviet Union and the establishment of communism, scientific socialism, throughout the world. I don’t have any doubt that they would be delighted if we would unilaterally disarm.

I want to say this to you, peace is not the greatest objective. It’s what attains peace or what is concomitant to peace. We could have peace next week. Reagan call up the Soviet Union, the First Secretary and say, “We are now about to destroy our nuclear devices. Come on over and help us with our problems and overcome a twenty year, forty divisions from the Soviet Union,” and we would have peace. It just wouldn’t be free. People like me would be quickly killed.