TaraShea Nesbit’s The Wives of Los Alamos tells the collective story of the women who moved to Los Alamos to be with their scientist husbands during the Manhattan Project. Collective story, that is, because the book is written in a distinct and novel manner: the first person plural. “Our husbands joined us in the kitchen and said, We are going to the desert, and we had no choice except to say, Oh my! as if this sounded like great fun. Where? we asked, and no one answered.” While this style choice might seem to be limiting, Nesbit is able to get across the range of emotions and personalities that made up the wives of Los Alamos. Drawn from real stories – including a few that likely came from the Atomic Heritage Foundation’s “Voices of the Manhattan Project” oral history website – The Wives of Los Alamos is a lyrical and realistic glimpse into the complicated and secretive life of the women who accompanied their husbands to an unknown town to work on an unknown project.

Nesbit writes beautifully, and she is able to bring individual personalities into the mix of her collective narrator. Some women love Los Alamos, some hate it. Some wives are happy to be in the dark about what their husbands are working on, while others do their best to find out what the great secret is. Nesbit explores the women’s connection with their Pueblo Indian maids and the young Army soldiers on the base. The Wives of Los Alamos does an excellent job of weaving together the stories of many different communities and age groups, and the ways in which the project to build the bomb upended their lives.

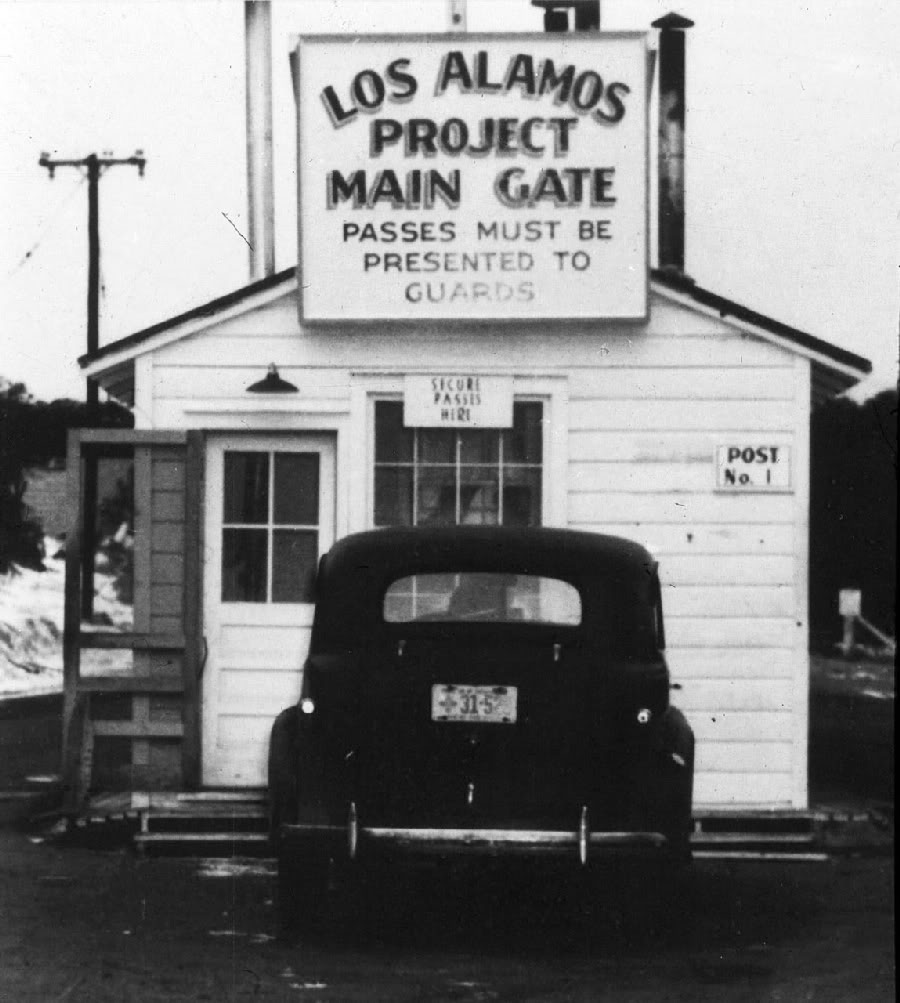

Nesbit chose to change the names of some of the real-life characters she based the book on. For example, one character is presented as the wife of a scientist who could only be Edward Teller. In the fiction, it is a little disconcerting, for those who know the history well, that the character’s name is “Helen” instead of Teller’s wife’s real name, “Mici.” “Robert,” the lone scientist who chooses to leave the project in December 1944, is based on Joseph Rotblat, who later won the Nobel Peace Prize for founding the Pugwash Conferences and promoting nonproliferation of nuclear weapons. Using the real names at least in some instances might have made it easier for people to look up further information about the scientists and their wives. But the use of surrogate names is reminiscent of the Manhattan Project‘s security officials who insisted on calling Enrico Fermi “Mr. Farmer” and Niels Bohr “Mr. Baker” despite the fact they were internationally known Nobel laureates, and further underscores the secrecy the wives encountered at Los Alamos.

Nesbit chose to change the names of some of the real-life characters she based the book on. For example, one character is presented as the wife of a scientist who could only be Edward Teller. In the fiction, it is a little disconcerting, for those who know the history well, that the character’s name is “Helen” instead of Teller’s wife’s real name, “Mici.” “Robert,” the lone scientist who chooses to leave the project in December 1944, is based on Joseph Rotblat, who later won the Nobel Peace Prize for founding the Pugwash Conferences and promoting nonproliferation of nuclear weapons. Using the real names at least in some instances might have made it easier for people to look up further information about the scientists and their wives. But the use of surrogate names is reminiscent of the Manhattan Project‘s security officials who insisted on calling Enrico Fermi “Mr. Farmer” and Niels Bohr “Mr. Baker” despite the fact they were internationally known Nobel laureates, and further underscores the secrecy the wives encountered at Los Alamos.

Nesbit’s book raises the bar for historical fiction. Readers who enjoy innovative story styles will like the book; people who prefer a more straightforward structure may not. We welcome The Wives of Los Alamos as an excellent contribution to the literature of Los Alamos and women in the Manhattan Project.

While often overlooked by historians, Nesbit conveys the many ways in which the wives of Los Alamos contributed as part of the project and in establishing a community for their families. To hear more stories from these women and other Manhattan Project participants, check out the Atomic Heritage Foundation’s “Voices of the Manhattan Project” website.