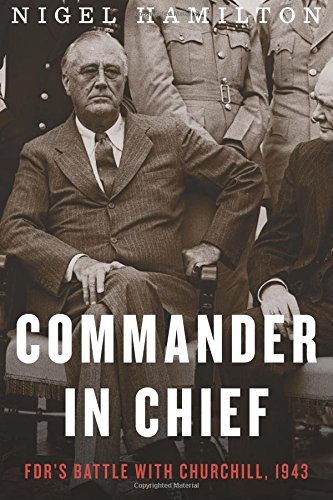

A great deal has already been written about Franklin Delano Roosevelt, one of the United States’ most beloved presidents. It comes as no surprise, then, that in order to tread new ground in the field of FDR scholarship, Nigel Hamilton’s new book hones in on a very specific subject. Commander in Chief: FDR’s Battle with Churchill, 1943 (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016) is a follow-up to his 2014 entry The Mantle of Command: FDR at War, 1941-1942. It focuses on Roosevelt as a military leader, and specifically on the year 1943, from the planning of the Casablanca Conference to the Allied invasion of mainland Italy. Presumably Mr. Hamilton is working on a follow-up volume focusing on the same topic for 1944 and 1945.

The specificity of the subject matter does not hurt the book’s readability. Commander in Chief weaves together compelling storylines, backed by a wealth of primary source material, on Roosevelt’s handling of the war. The focus is often on his clashes with advisers and fellow Allied leaders; in fact, the president’s actual World War II enemies, the Axis Powers, take a back seat to “allies” foreign and domestic who oppose his strategies. These opponents range from his Chief of Staff resisting the ailing president’s desire to fly across the Atlantic, to Josef Stalin refusing to meet and discuss the future of world politics.

As the book’s subtitle suggests, Roosevelt’s biggest tiff was with British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, whom Hamilton is fond of calling Roosevelt’s “active and ardent lieutenant” (the irony has diminishing returns with each use). As Hamilton tells it, Churchill resisted Overlord (the operation that would be known as D-Day) at every turn, arguing instead for a hodgepodge of other options: an invasion in 1945/6, an advance through the Balkans or Norway, a bigger offensive in Italy.

The problem with portraying World War II and FDR through these clashes is that Commander in Chief often slips from biography into hagiography. In each case, Hamilton is unambiguously on Roosevelt’s side. Frustratingly, he often presents a flimsy case for why, exactly, Roosevelt was right and everyone else was wrong. Rather than addressing opposing viewpoints head-on, he resorts to language dismissive of FDR’s adversaries and unflattering descriptions of their personalities. Hamilton’s other arguments are often repetitive and based on counterfactuals. For example, he states that a 1943 cross-Channel invasion would have been doomed to fail because of American troops’ lack of battle experience, and then repeats this assertion ad nauseam. These argumentative techniques would be expected from a newspaper opinion column, but not from a respectable biography.

This is not to say that Roosevelt was never right about strategy, simply that Hamilton does not entertain any other possible conclusion. A more balanced account might present the arguments for each side with equal weight, and explain what made these decisions so difficult and contentious. But Commander in Chief is not that account. Much time is spent on Roosevelt’s insistence on unconditional surrender and how it would form a basis for the new, United Nations-ruled international system. The surrender doctrine is portrayed as a way to avoid the sins of the Treaty of Versailles and prevent the Axis nations from re-arming. No mention is given of the fact that Versailles included a number of provisions aimed at preventing rearmament, or of the theory that the surrender doctrine may have lengthened the war in the Pacific.

The clear bias toward FDR is understandable, but it still weakens the biography’s effect. Another weakness is the confusing tangle of military leaders, both British and American, whom the text fails to distinguish from each other. Commander in Chief, at times, reads like an academic paper requiring intense attention to detail, rather than the narrative history it is clearly trying to be. It is possible that reading this back-to-back with The Mantle of Command would mitigate this issue. But without that, the reader may be left confused by the laundry list of generals and admirals.

All that aside, Commander in Chief does present a detailed look at the Western Allies’ military command apparatus. It also does a great job linking decisionmaking to human stories, including the principal actors’ personalities and relationships with one another. The style of the book keeps it engaging as well. Several “Parts,” each corresponding to an event, are divided up into smaller, vignette-length chapters. This keeps the pace moving along, which is no small feat, considering the highly specific subject matter.

Commander in Chief is well-suited for World War II buffs, but perhaps not so much for presidency buffs. The discussion of military strategy certainly seems comprehensive (though the Manhattan Project only merits a few passing mentions), but the discussion of FDR is not. He is portrayed as conflicted and even flawed, but never as fallible.

For more information about Roosevelt, see AHF’s new profile of him. For more on Anglo-American cooperation, see the article on Britain’s Early Input into the Manhattan Project.