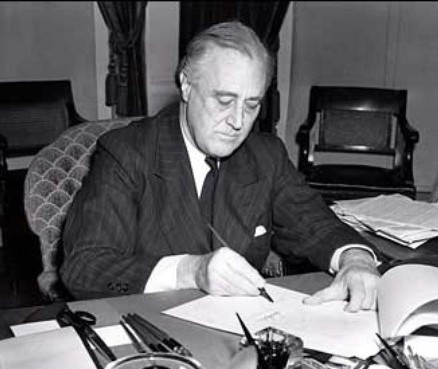

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (1882 – 1945) was the 32nd President of the United States of America.

Under Roosevelt’s tenure as President, the Manhattan Project was set into motion. He had direct responsibility for establishing and funding the project and its forerunners. Before his death in office in 1945, he made decisions that would influence the eventual choice to drop the atomic bombs on Japanese cities, as well as post-war nuclear policy.

BEFORE THE WAR

In October 1939, economist Alexander Sachs arranged a meeting with Roosevelt in order to present the famous letter from Albert Einstein and Leo Szilard, detailing the benefits of nuclear research, as well as the harm that could come from potential weapons. At the end of Sachs’s summary of the letter, Roosevelt responded, “Alex, what you are after is to see that the Nazis don’t blow us up.” Roosevelt took action, approving the formation of what became the Advisory Committee on Uranium (Uranium Committee), headed by Bureau of Standards Director Lyman J. Briggs. The Committee’s first meeting, later that month, involved some of the scientists who would go on to contribute to the Manhattan Project: Szilard, Eugene Wigner, and Edward Teller.

In 1940, Roosevelt gave a speech to the Pan American Scientific Congress, where he discussed some of the moral concerns scientists had about wartime. Speaking about the ongoing war in Europe, he said, “What has come about has been caused solely by those who would use, and are using, the progress that you have made along lines of peace in an entirely different cause.” Later the same year, he approved his adviser Vannevar Bush’s plan for a National Defense Research Council (NDRC), which subsumed the Uranium Committee.

The NDRC, however, was without a source of independent funding. In 1941, Roosevelt created the Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD) by executive order as a part of the Office for Emergency Management, with Bush as its director. The Uranium Committee became a part of the OSRD, codenamed S-1. A few months later, Bush met with the President and relayed the findings of the MAUD Committee Report from Britain, which focused on the theory behind the bomb and cautioned about German advances in that area. In response, Roosevelt formed what became known as the “Top Policy Group” to make future decisions about atomic policy, cutting out many of those actually working on the technology.

Further steps toward the birth of the Manhattan Project came in unofficial ways from the Oval Office. Bush and Roosevelt had agreed privately that the OSRD could not handle the atomic project alone, and the President agreed to secure funding for that enterprise. In January 1942, Roosevelt implicitly endorsed the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) Report, which encouraged pursuing a weapon, with a note to Bush.

DURING THE WAR

On December 7, 1941, Japanese fighters carried out a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, leading to the US entering the war. In 1942, Roosevelt approved a plan to have the Army Corps of Engineers assist in the uranium project, leading to the establishment of the Manhattan Engineer District (MED) and the official start of the Manhattan Project. In December of that year, Roosevelt approved $500 million for the project, further confirming his support for the project.

Niels Bohr met with the President in August 1944 to suggest some sort of international regime for controlling nuclear weapons after the war. Roosevelt and Winston Churchill, meeting a month later, rejected Bohr’s plan and any other that would involve cooperation with the Soviet Union. At that same meeting, a secret memo beween the two leaders confirmed Japan as the target for an atomic bomb, should one be developed. In a conversation between Roosevelt and Secretary of War Henry Stimson that year, the latter encouraged an eventual quid pro quo with the Russians, but cautioned against revealing the secret weapon at that point in time.

Roosevelt died on April 12, 1945. He was succeeded by his Vice President, Harry S. Truman. Truman was informed of the existence of the Manhattan Project and eventually approved the use of the atomic bombs against Japan.

OTHER IMPACTS ON THE PROJECT

As President, Roosevelt affected the Manhattan Project in ways beyond authorizing the project itself and its predecessor organizations. He was helpful, for example, in setting up some of the corporate participation in the bomb’s development. When DuPont was initially reluctant to participate, a call from Roosevelt to the company’s president convinced them to join the effort.

Roosevelt’s decisions in other areas also affected life for Manhattan Project workers. His 1941 Executive Order 8802 banned racial discrimination “in the employment of workers in defense industries of Government.” This led to the hiring of a number of Black and Hispanic workers at the various Manhattan Project sites. However, because segregation was still allowed, the accomodations and facilities for non-White workers were often inferior at sites like Hanford and Oak Ridge.