Tucked between the sprawling fields and open pastures that frame the rural village of Rhydymwyn in northeast Wales lies a mysterious patch of narrow land. Shielded by towering oak trees and overgrown brush, a closer look reveals a vast expanse of abandoned lots surrounded by rusting barb-wired fence. A series of empty brick structures dot the landscape, their sides covered with moss and faded by time. For more than half a century, the ghostly complex has remained a mystery—until now.

On August 27, 1939, just days before the outbreak of the second World War, Britain’s Treasury approved £546,000 for the development of a top-secret chemical weapons plant and storage facility in North Wales. Experts from the Imperial Chemical Industries Company (ICI), Britain’s largest manufacturer of chemical weapons, chose the secluded Rhydymwyn Valley Works as it’s new production facility.

The product? Mustard gas: a toxic, blistering agent that causes temporary blindness and, if inhaled, destruction of lung tissue. The gas was first used during World War I with devastating effects. With another world war looming in the 1930s, the threat from chemical weapons was very real. Britain and other major powers considered their production necessary, if only as a means of deterrence.

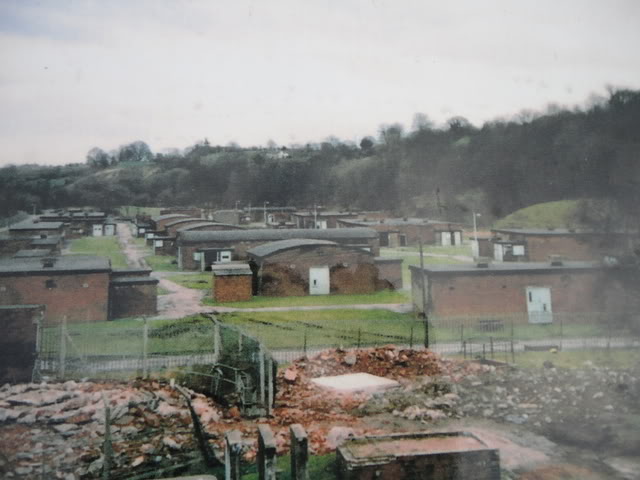

Valley Works, which became operational in 1941, was built on a long narrow plot of land beside the Alyn River and was divided into several distinct zones. This served not only to separate the various hazardous stages in the productions of munitions, but also to maintain secrecy. The compartmentalization ensured that workers at the site were unaware of the detail of operations in other facilities.

The site included a vast network of underground tunnels and bombproof caverns to store more than 1,500 tons of Mustard Gas produced at a nearby facility in Runcorn. Facilities for charging, bonding, and assembling the shells were also constructed at the Valley Works. In 1942, construction began on five buildings to produce the toxic mustard gas, though only two of these facilities actually produced the agent. By 1943, there were 2,200 people working in over 100 buildings at Valley Works.

The site included a vast network of underground tunnels and bombproof caverns to store more than 1,500 tons of Mustard Gas produced at a nearby facility in Runcorn. Facilities for charging, bonding, and assembling the shells were also constructed at the Valley Works. In 1942, construction began on five buildings to produce the toxic mustard gas, though only two of these facilities actually produced the agent. By 1943, there were 2,200 people working in over 100 buildings at Valley Works.

But among the storage facilities and maze of underground tunnels, Rhydymwyn was also hiding something else: research and development associated with “Tube Alloys,” the codename for the British effort to develop an atomic bomb. Between 1942 and 1946, British scientists carried out research on gaseous diffusion, one of the proposed methods to separate the fissile Uranium-235 from the heavier, more abundant Uranium-238.

Britain’s effort to build an atomic bomb had begun in 1940, after physicists Otto Frisch and Rudolf Peierls at the University of Birmingham determined that such a weapon would only require several kilograms of fissionable material to produce an atomic explosion. In order to separate uranium isotopes, British physicists favored gaseous diffusion—a method that would separate U-235 from U-238 based on the small differences in atomic weight.

In 1942, Rhydymwyn’s building P6 was selected to develop and test the gaseous diffusion process. Although constructed to manufacture mustard gas, the building was never outfitted with the manufacturing machinery. Plant officials inserted partition walls, constructed physics and chemistry workshops, and set up a glassblower’s laboratory. Several enormous Gaseous diffusion cells were delivered and installed in stages to test the process.

In 1942, Rhydymwyn’s building P6 was selected to develop and test the gaseous diffusion process. Although constructed to manufacture mustard gas, the building was never outfitted with the manufacturing machinery. Plant officials inserted partition walls, constructed physics and chemistry workshops, and set up a glassblower’s laboratory. Several enormous Gaseous diffusion cells were delivered and installed in stages to test the process.

“There were about a dozen of us laboratory assistants there,” recalls Myfanwy Prichard-Roberts, who was assigned to Rhydymwyn in 1942 after enrolling in the Women’s Technical Service Register. “This big plant, P6, I’d never been in such a building before and it was divided up into offices. There was a chemistry lab, a physics lab running down the right of the building, and a glass blowing cubical.”

The research and development effort at Rhydymwyn was led by Rudolf Peierls and included dozens of physicists and industrial chemists as well as several female laboratory assistants. Eileen Doxford was one of ten women recruited from a national base to help test equipment prototypes. “I worked with this glass apparatus and there was a little instrument attached to this which was called a pirani, which earned me the name of Pirani Queen,” recalls Eileen. “I had to calibrate what was happening in this glass apparatus and pump it down below atmospheric pressure and I would have a piece of graph paper and down one side I would put the pressures as it went down and along the bottom would be the time.”

For security purposes, the P6 building was sealed off and all employees were segregated from other workers at the site. Many had no idea that they were working on a process to enrich uranium for an atomic bomb. “We didn’t know what the work was all about, we just did as we were told and we never asked questions because we weren’t encouraged to find out what was going on,” says Myfanwy. “And we never did, not until after the war.”

The mysterious activity at P6 did not prevent rumors from swirling, however. “There is a story that went around,” says Myfanwy. “Some people took a van from Rhydymwyn one evening to meet a plane from America that was bringing some uranium in…all they came away with was just a small box.”

The mysterious activity at P6 did not prevent rumors from swirling, however. “There is a story that went around,” says Myfanwy. “Some people took a van from Rhydymwyn one evening to meet a plane from America that was bringing some uranium in…all they came away with was just a small box.”

Assisting Peierls at Rhydymwyn was Klaus Fuchs, a German theoretical physicist who fled to Britain in 1933 to escape Nazi persecution. In December 1943, Peierls and Fuchs travelled to New York to meet with General Leslie Groves and Manhattan Project leaders involved in gaseous diffusion. The following spring, Fuchs was transferred to Los Alamos where he joined the Theoretical Division and helped work on the lens system for the implosion bomb. It was later discovered that Fuchs was passing atomic secrets to the Soviet Union.

As the Manhattan Project expanded in size and scope, work at Rhydymwyn slowed and in 1945 P6 was converted into a general storage facility. Soon after, Valley Works halted mustard gas production and many buildings were demolished or converted into storage facilities. In 2003, the site underwent major remediation and a Visitor Centre was built on the site of the old gatehouse.

Today, the Rhydymwyn Valley Works site is a flourishing nature preserve, home to a wide variety of plants and wildlife. Visitors to the site can still take a tour through an eerie maze of underground tunnels and marvel at the huge bombproof caverns that once stored mustard gas.

For more information about Valley Works and to hear first hand accounts of those who worked there during World War II, please visit the Rhydymwyn Valley History Society’s website.