Amid a bitter rivalry with India, Pakistan became a nuclear power after testing its first bombs in 1998.

Early Years

Pakistan began its nuclear efforts during the 1950s as an energy program. It was prompted in large part by the United States’ “Atoms for Peace” program, which sought to spread nuclear energy technology across the globe. In 1956, the Pakistani government created the Atomic Energy Commission (PAEC) to lead the new program. The United States gave Pakistan its first reactor—the five megawatt Pakistan Atomic Research Reactor (PARR-1)—in 1962.

During this early period, PAEC chairman Ishrat Usmani devoted government resources to training the next generation of Pakistani scientists. Usmani founded the Pakistan Institute of Nuclear Sciences and Technology (PINSTECH) in 1965 and sent hundreds of young Pakistani students to be trained abroad.

Although Pakistan claimed that its nuclear program was only pursuing peaceful applications of atomic energy, there were signs that its leadership had other intentions. This fact was particularly evident in wake of the 1965 Indo-Pakistani War, which ended in a nominal victory for India. “If India builds the bomb, we will eat grass or leaves, even go hungry, but we will get one of our own,” proclaimed then-Minister of Foreign Affairs Zulfikar Ali Bhutto.

Weapons Development

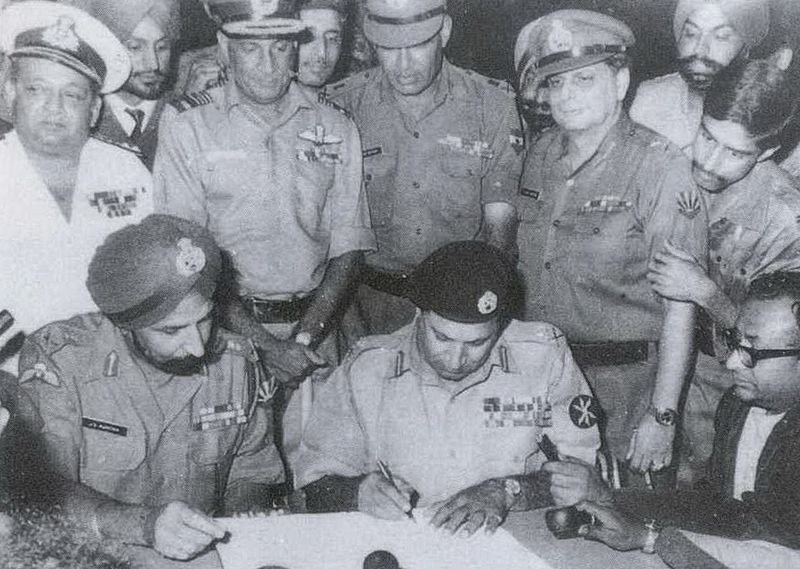

In 1971, war once again broke out between India and Pakistan. The conflict began when Pakistan conducted preventative strikes against Indian airfields which nonetheless failed to seriously cripple India’s Air Force. In response, India launched a ground campaign in support of the ongoing secession movement in East Pakistan, which would soon become independent Bangladesh. Pakistan sustained heavy losses, and almost 100,000 Pakistani soldiers were taken prisoner. Within two weeks, Pakistan surrendered.

In 1971, war once again broke out between India and Pakistan. The conflict began when Pakistan conducted preventative strikes against Indian airfields which nonetheless failed to seriously cripple India’s Air Force. In response, India launched a ground campaign in support of the ongoing secession movement in East Pakistan, which would soon become independent Bangladesh. Pakistan sustained heavy losses, and almost 100,000 Pakistani soldiers were taken prisoner. Within two weeks, Pakistan surrendered.

The humiliation of 1971 was a turning point in Pakistan’s decision to build an atomic bomb. In 1972, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto—soon to be elected Prime Minister—called a meeting in which he instructed top Pakistani scientists to build the bomb. Physicist Munir Ahmad Khan was among the scientists invited to the meeting. Trained in the United States at the Illinois Institute of Technology, Khan had worked at Argonne National Laboratory and served as head of reactor engineering for the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). He was quickly named chairman of PAEC and would lead the new direction of Pakistan’s nuclear program.

Around the same time, Pakistan began receiving considerable international support for its nuclear program. Canada, for example, provided a 137-megawatt heavy water nuclear reactor known as Canada Deuterium Uranium (CANDU). The reactor was installed at the Karachi Nuclear Power Plant (KANUPP) and was soon producing weapons grade plutonium. France likewise agreed to supply the Chashma plutonium separation plant. Nevertheless, the international community cracked down on the proliferation of nuclear materials after India’s first nuclear test in 1974. Canada withdrew its support for Pakistan in 1976, while France never completed the Chashma plant. A plutonium bomb suddenly seemed like a distant reality.

Project-706

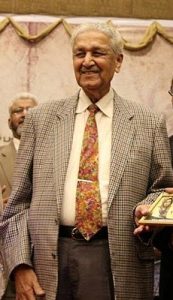

In December 1974, however, the course of the Pakistani bomb drastically changed with the return of German-trained metallurgist Abdul Qadeer Khan, more commonly known as A. Q. Khan. He had spent the previous four years working for URENCO, a nuclear fuel company, on uranium enrichment plants in the Netherlands and brought his vast knowledge of gas centrifuges to Pakistan. Over several decades, Khan would proliferate this technology to a whole host of would-be nuclear powers, including Iran, North Korea, and Libya.

In December 1974, however, the course of the Pakistani bomb drastically changed with the return of German-trained metallurgist Abdul Qadeer Khan, more commonly known as A. Q. Khan. He had spent the previous four years working for URENCO, a nuclear fuel company, on uranium enrichment plants in the Netherlands and brought his vast knowledge of gas centrifuges to Pakistan. Over several decades, Khan would proliferate this technology to a whole host of would-be nuclear powers, including Iran, North Korea, and Libya.

Although he was never officially head of Pakistan’s nuclear program, Khan played a vital role in its success. In 1976, he was put in charge of the Engineering Research Laboratories in Kahuta, which was later named the Khan Research Laboratories (KRL). The site of a uranium enrichment plant, KRL offered Pakistan a second path to the bomb via highly enriched uranium (HEU) rather than plutonium. Khan’s laboratory was mostly autonomous from PAEC and the uranium bomb project even had a special codename: Project-706.

Although Project-706 began under Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, his influence over the project was short-lived. In 1977, General Muhammad Zia ul-Haq took power in a coup d’état and hanged Bhutto in 1979. The military took control of the nuclear program and it remains under military control today despite Pakistan later returning to a civilian government.

In 1979, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan had a significant impact for Pakistan. Under President Ronald Reagan, the United States gave military support to the Afghan mujahideen to fight the Soviet Union. Pakistan—a neighbor of Afghanistan with crucial supply routes—proved to be an essential ally in this effort. As a result, the United States largely turned a blind eye to the Pakistani nuclear program. In 1982, for example, Zia made an official visit to the United States. “He’s a good man,” wrote Reagan in his diary. “Gave me his word they were not building an atomic or nuclear bomb. He’s dedicated to helping the Afghans & stopping the Soviets” (Reed and Stillman 249).

In 1985, the U.S. Congress passed the Pressler Amendment, which established a protocol for sanctions against Pakistan if it crossed certain “red lines,” such as manufacturing highly enriched uranium and making a fissionable bomb core. The law was designed to allow the United States to maintain good relations with Pakistan, but it ultimately forced the American government to implement sanctions in the 1990s.

Beginning in the early 1980s, Pakistan conducted a series of “cold tests,” which involved a nuclear device without fissile materials. It conducted over 20 additional cold tests during the next decade. Pakistan also strengthened its alliance with China against India. Among other assistance to Pakistan’s nuclear program, the Chinese government invited Pakistani scientists to Beijing. On May 26, 1990, China tested a Pakistani bomb (Pak-1) on Pakistan’s behalf at the Lop Nur test site. The so-called “Event No. 35” was most likely a uranium implosion bomb, a derivative of the Chinese CHIC-4 design. Pakistan also reached an agreement with North Korea for Nodong ballistic missiles in exchange for Pakistani uranium enrichment technology.

Nuclear Tests

During the 1990s, Pakistan prepared for possible testing. Project officials selected the Ras Koh Hills in the southwestern Baluchistan province as a test site. Engineers drilled test shafts deep into the ground in preparation. Pakistan also vastly improved its missile technology, developing the Ghauri medium-range ballistic missile, a derivate of the North Korean Nodong.

During the 1990s, Pakistan prepared for possible testing. Project officials selected the Ras Koh Hills in the southwestern Baluchistan province as a test site. Engineers drilled test shafts deep into the ground in preparation. Pakistan also vastly improved its missile technology, developing the Ghauri medium-range ballistic missile, a derivate of the North Korean Nodong.

Prime Minister Mohammad Nawaz Sharif faced enormous pressure to authorize nuclear tests after India conducted its own tests in May 1998. “We in Pakistan will maintain a balance with India in all fields,” said Foreign Minister Gohar Ayub Khan, a proponent of testing. “We are in a headlong arms race on the subcontinent.” International leaders, however, called on Sharif not to respond to the Indian tests. The United States even offered a repeal of the Pressler Amendment and additional military aid should Pakistan refrain from testing.

In the end, however, Pakistani officials went ahead with preparations for the test—codenamed Chagai-I—when Sharif gave the order “Dhamaka kar dein” (conduct the explosion). A military escort flew the bomb parts to Ras Koh, where they were assembled and placed in the test shafts along with diagnostic cables. On May 28, 1998—less than three weeks after India’s nuclear tests—Pakistan exploded its first devices at the Ras Koh test site. “Today, we have settled a score and have carried out five successful nuclear tests,” announced Sharif. With a total yield of 9 kilotons, however, there is some debate about how many bombs were actually tested (Reed and Stillman 257). Two days later, Pakistan conducted an additional test, Chagai-II.

Pakistan Today

Unlike India, Pakistan does not have a no first use doctrine regarding its nuclear arsenal. In the aftermath of the 1998 tests, Prime Minister Sharif affirmed that the Pakistani bomb was “in the interest of national self-defense…to deter aggression, whether nuclear or conventional.” In 2002, President Pervez Musharraf declared that Pakistan would “respond with full might” if attacked.

Unlike India, Pakistan does not have a no first use doctrine regarding its nuclear arsenal. In the aftermath of the 1998 tests, Prime Minister Sharif affirmed that the Pakistani bomb was “in the interest of national self-defense…to deter aggression, whether nuclear or conventional.” In 2002, President Pervez Musharraf declared that Pakistan would “respond with full might” if attacked.

After 9/11, the United States grew very concerned that political instability and religious radicalism in Pakistan could give non-state actors such as the Taliban access to nuclear materials. With help from the West, the Pakistani government took steps to improve its nuclear security, although concerns remain today.

The civilian National Command Authority (NCA) maintains command and control of Pakistan’s nuclear weapons. As of 2016, the Nuclear Threat Initiative estimates the Pakistani arsenal at 100-120 warheads, but with materials for more than 200.