On November 3, 1944, Japan released fusen bakudan, or balloon bombs, into the Pacific jet stream. They each carried four incendiaries and one thirty-pound high-explosive bomb. Japan’s latest weapon, the balloon bombs were intended to cause damage and spread panic in the continental United States. The balloons would claim six American lives on May 5, 1945, but they were widely considered a military failure. Japan halted the operation in April 1945.

Creation of the Fu-Go

The Japanese Military Scientific Laboratory originally conceived of the idea of balloon bombs in 1933. Their Proposed Airborne Carrier research and development program explored several ideas, including the initial idea of balloon bombs, according to Robert Mikesh. His scholarly report on these Fu-Go balloons is a definitive work on this obscure topic.

The idea of the balloon bombs returned when Japan sought to retaliate after the Doolittle Raid, which revealed Japan to be vulnerable to American air attacks. The 9th Military Technical Research Institute, better known as the Noborito Research Institute, was charged with discovering a way to bomb America, and they revived the idea of Fu-Go. They designed balloon bombs to be launched from Japanese submarines on the West Coast of America. The joint army-navy research into this operation came to an abrupt halt, however, when every submarine was recalled for the Guadalcanal operation in August 1943.

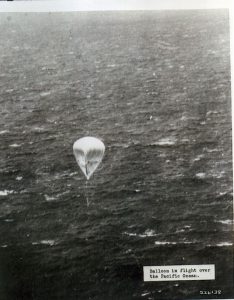

New efforts were then focused on designing a transpacific balloon, one that could be launched from Japan and reach the continental USA. In the winter of 1943 and 1944, meteorologists, with support from the engineers tasked to develop transpacific balloons, tested the winter jet stream. They discovered that a balloon could hypothetically travel on average 60 hours on this jet stream and successfully reach America.

This discovery greenlighted the mass production of 10,000 balloons in preparation for the winter winds of 1944 and 1945. The balloons were to be made of washi, a paper made from the bark of the kozo tree, and schoolgirls from neighboring schools were to be the labor force, conscripted as part of the total war effort mindset preached by the Japanese Empire. The girls, however, would not be told what they were making.

Finally, on the auspicious day of November 3, 1944, chosen for being the birthday of former Emperor Meiji, the first of the balloons were launched. Launching proved to be difficult as it took 30 minutes to an hour to prepare one balloon for flight, and required approximately thirty men. In addition, the balloons could only be launched during certain wind conditions. In the months of November to March, there were only 50 anticipated favorable days, and they expected to launch a maximum of 200 balloons from their three launch sites per day.

Despite the launches being top secret, once released, balloons were not hidden to those in the neighboring areas. Witnesses remembered these “giant jellyfish” drifting off into the sky, Mikesh details.

American Reaction

Two days after the initial launch, a navy patrol off the coast of California spotted some tattered cloth in the sea. Upon retrieval, they noted its Japanese markings and alerted the FBI. It wasn’t until two weeks later, when more sea debris of the balloons were found, that the military realized its importance. Then, over the next four weeks, various reports of the balloons popped up all over the Western half of America, as Americans began spotting the cloth or hearing explosions.

Edward Melkonian. Photograph courtesy of Karen Melkonian.

The initial reaction of the military was immediate concern. Little was known about the purpose of these balloons at first, and some military officials worried that they carried biological weapons. They suspected that the balloons were being launched from nearby Japanese relocation camps, or German POW camps.

In December 1944, a military intelligence project began evaluating the weapon by collecting the various evidence from the balloon sites. An analysis of the ballast revealed the sand to be from a beach in the south of Japan, which helped narrow down the launch sites. They also concluded that the main damage from these bombs came from the incendiaries, which were especially dangerous for the forests of the Pacific Northwest. The winter was the dry season, during which forest fires could turn very destructive and spread easily. Yet overall, the military concluded that the attacks were scattered and aimless.

Because the military worried that any report of these balloon bombs would induce panic among Americans, they ultimately decided the best course of action was to stay silent. This also helped prevent the Japanese from gaining any morale boost from news of a successful operation. In January 4, 1945, the Office of Censorship requested that newspaper editors and radio broadcasts not discuss the balloons. The silence was successful, as the Japanese only heard about one balloon incident in America, through the Chinese newspaper Takungpao.

In February 17, 1945, the Japanese used the Domei News Agency to broadcast directly to America in English and claimed that 500 or 10,000 casualties (the news accounts differ) had been inflicted and fires caused, all from their fire balloons. The propaganda largely aimed to play up the success of the Fu-Go operation, and warned the US that the balloons were merely a “prelude to something big.”

The American government, however, continued to maintain silence until May 5, 1945. In Bly, Oregon, a Sunday school picnic approached the debris of a balloon. Reverend Archie Mitchell was about to yell a warning when it exploded. Sherman Shoemaker, Edward Engen, Jay Gifford, Joan Patzke, and Dick Patzke, all between 11 to 14 years old, were killed, along with Rev. Mitchell’s wife Elsie, who had been five months pregnant. They were the only Americans to be killed by enemy action during World War II in the continental USA.

Their deaths caused the military to break its silence and begin issuing warnings to not tamper with such devices. They emphasized that the balloons did not represent serious threats, but should be reported. In the end, there would be about 300 incidents recorded with various parts recovered, but no more lives lost.

The closest the balloons came to causing major damage was on March 10, 1945, when one of the balloons struck a high tension wire on the Bonneville Power Administration in Washington. The balloon caused sparks and a fireball that resulted in the power being cut. Coincidentally, the largest consumer of energy on this power grid was the Hanford site of the Manhattan Project, which suddenly lost power.

“We had built special safeguards into that line, so the whole Northwest could have been out of power, but we still were online from either end,” said Colonel Franklin Matthias, the officer-in-charge at Hanford during the Manhattan Project, in an interview with Stephane Groueff in 1965. “This knocked out the power, and our controls tripped fast enough so there was no heat rise to speak of. But it shut down the plant cold, and it took us about three days to get it back up to full power again.”

The balloon did not have any major consequences. Matthias recalled that although the Hanford plant did lose about two days of production, “we were all tickled to death this happened” because it proved the back-up system worked.

Vincent “Bud” Whitehead, a counter-intelligence agent at Hanford, recalled chasing and bringing down another balloon from a small airplane: “I threw a brick at it. I put a hole in it and it went down. I got out there and I start tromping all over that thing and got all the gas out of it. I radioed in that I had found it and got it. They sent a bus up with all of this specially trained personnel, gloves, full contamination suits, masks. I had been walking around on that stuff and they had not told me! They were afraid of bacterial warfare.”

Although balloon sightings would continue, there was a sharp decline in the number of sightings by April 1945, explains historian Ross Coen. By late May, there was no balloons observed in flight.

End of the balloons

Following the end of the war, a team of American scientists arrived in Tokyo in September to create a report on Japanese scientific war research. The team was co-headed by Karl T. Compton, a longtime scientific advisor to the US government, and Edward Moreland, a scientist hand-picked by General MacArthur. As part of their report, they interviewed officials from Noborito who had worked on the Fu-Go program.

Edward Melkonian. Photograph courtesy of Karen Melkonian.

On September 19, two Americans spoke with Lieutenant Colonel Terato Kunitake and a Major Inouye. They stated that all records of the Fu-Go program had been destroyed in compliance with a directive on August 15. This interview, and no official Japanese documents, was to be the only source of information regarding the objectives of the Fu-Go program for the US authorities, explains Coen.

The investigators learned that the Japanese had planned to make 20,000 balloons, but had fallen short of that mark. They also learned that the campaign was “designed to offset the shame of the Doolittle raid,” Coen notes. According to this interview, the Japanese Army had known that it would not be an effective weapon, but pursued it for the morale boost. When there were no reports of actual damage in the US, the Japanese media had made up fake stories about the weakening of American resolve. They also confirmed that there was no plan for biological or chemical warfare with the balloons.

According to the two men interviewed, the Army had stopped the balloon program because of a lack of resources. There were barely any more kozo trees, which was needed for the paper production. In addition, B-29s had bombed the Showa Denko chemical plant, which heavily limited Japan’s hydrogen resources. They said a second factor was the lack of information about whether the balloons even reached America and caused damage. They confirmed that even if the war had continued on for another year, the balloons would not have been used in the upcoming winter winds.

To this day, historians believe not all balloons have been recovered. While most are likely lost in the ocean, residents of the Pacific Northwest are advised to be careful when exploring uncharted territories. As recently as 2014, a balloon was discovered in Canada, and it was technically functional.

While the balloons failed to be an effective weapon, they were a product of wartime scientific innovation. When the first balloons arrived in America, they technically became the world’s first intercontinental ballistic missile.