The Dragon Bites Twice: “Tickling the Tail of the Dragon”

First in August of 1945 and again in May of 1946, two Los Alamos, NM scientists, Harry Daghlian and Louis Slotin, were exposed to lethal doses of radiation while performing experiments to determine critical mass. These experiments, performed at the Omega Site, were commonly referred to as “Tickling the Tail of the Dragon”. Although several months apart, both accidents occurred on a Tuesday and both on the 21st of the month, and ultimately both men died in the same hospital room at the U.S. Engineers Hospital at Los Alamos, NM.

On August 21, 1945, Daghlian was working on a criticality experiment, attempting to build a neutron reflector. He was working alone and late at night. While working on the experiment, the neutron counter indicated placing the last brick would cause the assembly to go supercritical. While slowly backing away before placing the tungsten carbide brick, he accidentally dropped it. Already having received the initial blast of neutron radiation, he disassembled the pile, exposing himself to additional gamma radiation. He died 25 days later at the hospital in Los Alamos.

On Tuesday, May 21, 1946, Louis Slotin was demonstrating a criticality experiment that involved gradually bringing together two beryllium-coated halves of a sphere that held plutonium at its core- without allowing the halves to touch- and recording the increasing rate of fissioning. Then, in one fateful moment, the screwdriver slipped.

A blue glow flashed from the sphere and the Geiger counter clicked furiously. Slotin, exposed to nearly 1,000 rads of radiation (well above a lethal dose), reacted instinctively and knocked the spheres apart. His action stopped the chain reaction and prevented the seven other individuals in the room from being exposed to the same high levels of radiation as he experienced. Slotin’s health rapidly deteriorated and he spent his last nine days receiving around-the-clock care as he went through the ravages of radiation sickness, passing away on May 30, 1946.

It was not until the second accident and Louis Slotin’s death that more rigorous safety procedures were applied. After the incident, criticality experiments at Los Alamos were conducted remotely, with roughly a quarter of a mile separating scientists from radioactive material. Their deaths helped incite a new era of health and safety measures.

The same plutonium core – nicknamed “the demon core” – was being used by Daghlian and Slotin at the time of their accidents. The plutonium core was intended to be the core of the third atomic bomb. However, Japan surrendered and the assembly was called off, resulting in the core being left in Los Alamos. The core was then intended for use in the Operation Crossroads nuclear tests, but after the criticality accident, time was needed for its radioactivity to decline and for it to be re-evaluated for the effects of the fission products it held, some of which were highly neutron poisonous to the desired level of fission. For more about the demon core and its fate, see historian Alex Wellerstein’s article, “The Third Core’s Revenge.” To hear an eyewitness account of the Slotin accident with Raemer Schreiber, click here.

The Philadelphia Incident

On September 2, 1944, three men entered the transfer room of the liquid thermal diffusion semi-works at the Philadelphia Navy Yard to repair a clogged tube. The tube they were working on consisted of two concentric pipes with liquid uranium hexafluoride circulating in the space between them and the innermost pipe contained high-pressure steam.

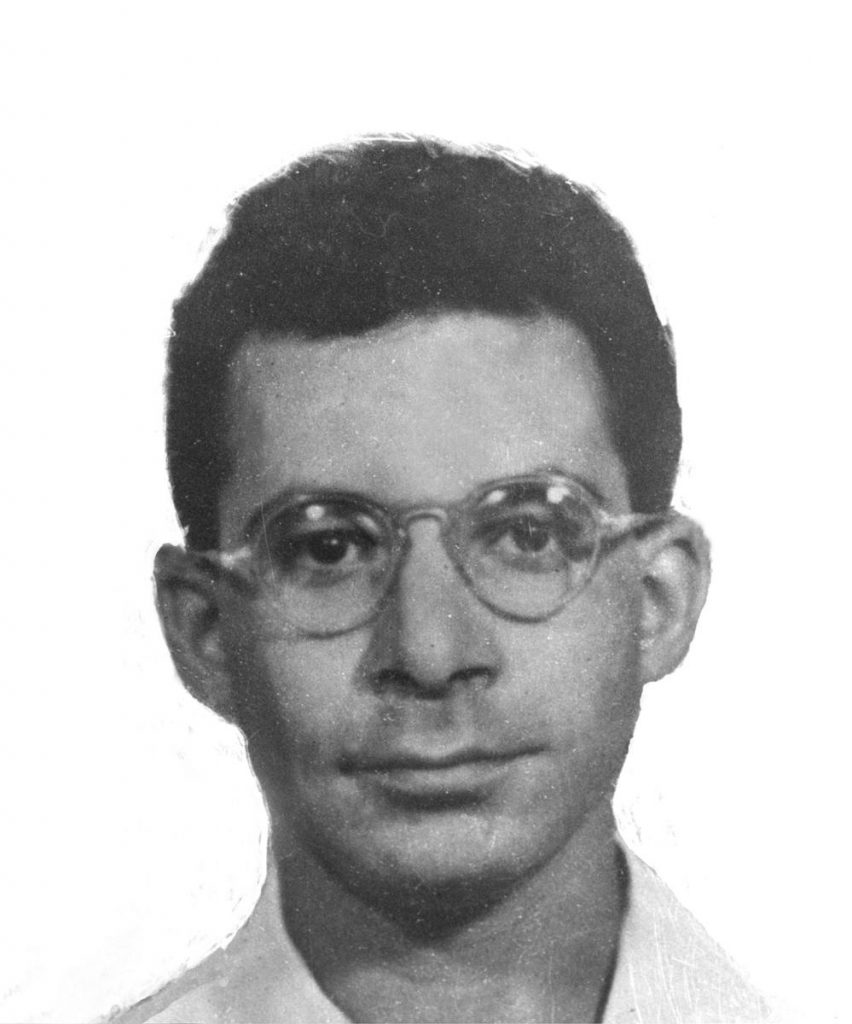

These men, all from different backgrounds and each representing a different facet of the complex Manhattan Engineer District, had one thing in common: they had all volunteered to work in a dangerous environment on a process that had only recently moved from the laboratory experimental stage to a pilot plant operation. Peter N. Bragg Jr., a chemical engineer from Arkansas, was hired in June by the Navy Research Lab; Douglas P. Meigs was an employee of the H. K. Ferguson Company of Cleveland, OH, the prime contractor for the thermal diffusion project; and Arnold Kramish, a physicist by education and a member of the Special Engineer Detachment (SED), was on loan from Oak Ridge, TN.

Kneeling on the floor with a Bunsen burner, Bragg and Meigs worked to free the clogged tube. Without warning, at 1:20 PM, there was a terrific explosion. As the tube shattered, the liquid uranium hexafluoride combined with the escaping steam and showered the two engineers with hydrofluoric acid, one of the most corrosive agents known. Within minutes, both Bragg and Meigs, with third degree burns all over their bodies, were dead and Kramish, also burned, was near death.

As the explosion ripped through the transfer room of the Naval Research Laboratory’s thermal diffusion experimental pilot-plant, the battleship U.S.S. Wisconsin sat berthed not more than two hundred yards away. Just back from its “shakedown” cruise, the sailors on board were never made aware that they had been exposed to a cloud of uranium hexafluoride, nor were the firemen and others who responded to the scene. Although not highly radioactive, the uranium hexafluoride was nevertheless toxic.

Due to the extreme secrecy surrounding the Manhattan Project and specifically this experimental facility at the Philadelphia Navy Yard, General Leslie Groves immediately drew a veil over the incident. A press release was entitled only “Explosion at Navy Yard.” Even the Philadelphia coroner was not made aware of the actual causes of death. It was not until many years later that the facts of the incident emerged.

small.jpg)