June 21, 2023 Newsletter

Congratulations to Los Alamos on being one of Smithsonian magazine’s top 15 best small towns to visit in 2023! Los Alamos is preparing for an influx of tourists from the “Oppenheimer” film and this great publicity. Bring them on!

This issue features the Manhattan Project interpreted four ways–by artworks, books, a radio program, and cinema. First, Oak RIdge in the 1940s comes alive in watercolors by Manhattan Project veteran Jan Myers. New books provide insights into Cormac McCarthy’s thoughts on the Manhattan Project; journalist Evan Thomas’s analysis of the end of World War II; and Miriam Hiebert’s detective story about a uranium cube from Nazi Germany’s ill-fated nuclear reactor project.

Next are a radio program and cinema. ABC Radio Adelaide has a show called “Brunch with Edward Teller” featuring Cindy Kelly talking about Edward Teller with audiences Down Under. A preview of Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer reports that author Kai Bird was “stunned” after watching the movie.

Finally, the National History Day contest brought 2,600 students, 600 teachers, and Heather McClenahan, former executive director of the Los Alamos Historical Society, to Washington, DC for a week. Enjoy!

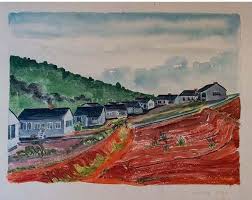

Oak Ridge in Watercolors

After her husband, Lawrence S. Myers, Jr.,was recruited to work at Oak Ridge, Jan Vanderwalder Myers decided to apply. With college courses in general and organic chemistry, she was hired as a chemist working along graduate students, PhDs, and professors in the Chemistry Building of Site X-10.

After living in dorms and then a 20 x 20 yellow “birdcage,” Jan and Larry were assigned to a two-bedroom cemesto house at 234 Vermont Avenue. Rent was $37 a month and included coal, water, and electricity. To Jan, it seemed palatial.

Jan was a very talented artist and created dozens of beautiful watercolors of Oak Ridge in the 1940’s (pictures above and below). Catherine Myers, Jan’s daughter, has generously donated the paintings to the Oak Ridge History Museum. Karla Mullen, director of the Museum, is thrilled:

“These colorful paintings are a wonderful complement to the Museum’s large collection of black-and-while photos by Ed Westcott. They vividly capture the red mud, rows of newly built houses, and the verdant green hills of Oak Ridge.”

Cormac McCarthy and the Manhattan Project

On Saturday, October 6, 2006, Cormac McCarthy came to the Atomic Heritage Foundation’s symposium, “Legacy of the Manhattan Project: Creativity in Science and the Arts.” Held in Los Alamos, the program featured Richard Rhodes (Making the Atomic Bomb), author Joseph Kanon (Los Alamos), composer John Adams (Doctor Atomic), and other luminaries. Sadly, McCarthy died on June 13, 2023.

For nearly forty years, McCarthy was a Senior Fellow at the Santa Fe Institute. Murray Gell-Mann, who won the Nobel Prize in physics in 1969, co-founded the Santa Fe Institute in 1984 and persuaded McCarthy to join him there. Over the next four decades, McCarthy made the Institute a second home, exploring mathematics, physics, and analytic ideas with scientists and scholars. He also enjoyed elaborate lunches and dinners with Murray Gell-Mann and other SFI researchers.

McCathy’s last two interrelated novels, The Passenger and Stella Maris (2022), reflect his interest in the Manhattan Project and its legacy. Each novel takes the perspective of one of the two children of a Manhattan Project couple. Their mother went to work at age 19 at Oak Ridge’s Y-12 electromagnetic separation plant. As McCarthy describes, when the switches were thrown for the first time, “hairpins in their hundreds shot from the women’s heads and crossed the room like hornets.”

She soon followed their father to Los Alamos. A physicist, their father remembered Oppenheimer. “You could take a problem you’d been working on for weeks and he would sit there puffing on his pipe while you put your work up on the board and he’d look for a minute and say: Yes. I think I see how we can do this. And get up and erase your work and put up the right equations and sit down and smile at you.” (The Passenger, p. 370)

Like his father, Bobby Western is a physicist. In his view, “Physics tries to draw a numerical picture of the world. I don’t know if that actually explains anything. You can’t illustrate the unknown. Whatever that might mean.” (The Passenger, p. 156.) But physics has left an imprint on Western even after becomes a racecar driver. His Maserati’s trident reminds him of Schrodinger’s wavefunction.

In Stella Maris, the main character is Bobby’s sister Alicia. She is a mathematical prodigy, entering the University of Chicago at age 13. But Alicia’s pursuit of revolutionary mathematical theories makes her question the nature of reality. Hallucinating, she checks herself into a psychiatric facility. The two novels raise many philosophical questions about religion, truth, and science and reflect the years Cormac McCarthy spent talking with Murray Gell-Man and others at the Santa Fe Institute.

In the Fog of War

Road to Surrender by Evan Thomas is a compelling account of the weeks leading to Japan’s surrender, a time of enormous uncertainty. With extensive new research, Evans offers historical insights into the minds and roles of three men: US Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson, Japan’s Foreign Minister Shigenori Togo, and US Army Strategic Air Force Carl Spaatz. Thomas writes his account in the present tense which heightens the sense of immediacy.

Secretary of War Henry Stimson closely oversaw the top-secret development of the atomic bomb and understood its potential destructive power. In June 1945, Stimson wants to bring an end to the war as quickly as possible but struggles with moral and postwar issues. Stimson objects to targeting Kyoto, the ancient capital of Japan, and believes that after the war, the bomb ought to be internationally controlled by “a group of enlightened wise men.”

Foreign Minister Shigenori Togo is one of the “Big Six,” members of the Supreme Council for the Direction of the War, who are committed “to fight to the bitter end.” In spring of 1945, Togo realizes that Japan is beaten but even using the word surrender is forbidden.

Togo quietly works to find ways to bring about peace. He futilely reaches out to the Soviet Union to mediate. The Hiroshima bomb is dropped on the morning of August 6. Two days later, Togo meets privately with Emperor Hirohito who agrees that “we must not miss a chance to terminate the war.”

However, Prime Minister Suzuki is unable to get the other four of the Big Six to convene to talk about the terms of surrender. They tell Suzuki they are “unavailable” or have “more pressing business.” From their country’s own failed attempt to make an atomic bomb, Japanese military leaders did not think that the US could possibly have more than one bomb.

In the early morning of August 9, Soviet troops invade Manchuria. The Big Six are still stymied. With no consensus recommendation, Emperor Hirohito makes an unprecedented decision to bring the war to an end immediately and accepts the terms of the Potsdam Declaration with the sole proviso that Japan be allowed to keep its emperor.

Hirohito records a message to be broadcast to the Japanese people announcing his decision. Anticipating a coup, Togo hides the recording and then transmits it in English in Morse code at 8 PM Tokyo time on August 10, 1945, to the Allies in Washington, DC and London.

Meanwhile, young military officers ask War Minister Amani to lead a coup. Amani refuses: “As a Japanese soldier, I must obey my Emperor.” At noon August 15, 1945, the Emperor’s radio message is heard throughout Japan urging the people to “bear the unbearable.”

Hirohito never uses the words for “surrender” or “defeat,” but describes the war situation as “not necessarily in Japan’s advantage.” Because of the “new and most cruel bomb,” if Japan continued to fight it would result in “the ultimate collapse and obliteration” of Japan and “the total extinction of human civilization.” Over the course of the war, well over 20 million people have died in Japan and her conquered territories.

In charge of the US Army Strategic Air Force, General Carl Spaatz runs the strategic air war against Japan including the delivery of the atomic bombs. He was deeply disturbed by the Dresden bombing and later the civilian casualties caused by the atomic bombs. After World War II as chief of the newly independent Air Force, he opposed the first use of nuclear weapons. At the end of his life, he talked about the “wrongness and folly of using nuclear weapons.”

While the overall story is well known, Evan Thomas makes the events immediate with riveting details from diaries of the three men and other sources. Thomas captures the unrelenting pressure, anxiety, and moral ambiguity that weighted heavily on the participants as they struggled to end a long and horrific war.

The Uranium Club

The Uranium Club reads like a fast-paced, compelling detective story. The impetus for the book is a five-inch uranium cube used by Nazi scientists in World War II that mysteriously ended up in a physics lab at the University of Maryland. The account weaves contemporary investigations with stories of the Alsos Mission. Led by the colorful Lieutenant Colonel Boris T. Pash, the risky undertaking sought to capture the scientists and materials of the Nazi efforts to develop an atomic bomb.

Over a thousand cubes of uranium metal were produced in Europe during World War II. Werner Heisenberg used 664 to create his failed cube reactor experiment in a limestone cavern in Haigerloch. Heisenberg’s rival Kurt Diebner, a second-rate army scientist, was first to experiment with uranium cubes. At the end of the war, Diebner had 400 cubes in his laboratory in Thuringia.

Only 14 of the uranium cubes are known to remain. Fortunately, the National Museum of Nuclear Science & History in Albuquerque has one on display.

Brunch with Edward Teller

Paul Gough, a producer for ABC Radio Adelaide in Australia, is presenting “Brunch with Edward Teller.” At 10 AM on Tuesday, June 20, 2023, audiences Down Under can join Gough and Atomic Heritage Foundation’s Cindy Kelly for a virtual brunch with Edward Teller.

Edward Teller was born into a Jewish family in 1908 in Budapest, Hungary. He was one of the so-called “Martians,” along with Eugene Wigner, John van Neumann, and Leo Szilard. Italian Enrico Fermi quipped that they must have been dropped off in Budapest by a spaceship from Mars. All four Hungarians were brilliant scientists who played leading roles in the Manhattan Project.

In 1926, the regime of Nicholas Horthy, an anti-Semitic fascist dictator, led Teller to leave Hungary to study in Germany. There he received his PhD in physics under Nobel laureate Werner Heisenberg.

When Hitler came to power in Germany in 1933, Teller too fled to London and then Copenhagen, working under Nobel laureate Niels Bohr. In 1934, he married his long-time sweetheart Augusta Harkanyl, known as “Mici” (pronounced “Mitzi”). The couple emigrated to Washington, DC where Teller worked for Russian émigré George Gamov at the George Washington University until 1941.

Teller joined the Manhattan Project at Los Alamos in 1943, where he worked in the theoretical division under Hans Bethe. However, Teller did not want to work on the fission-based atomic bomb. He was fascinated with the possibility of a much more powerful fusion bomb called the “Super” or hydrogen bomb. While J. Robert Oppenheimer strongly preferred that Teller focus on the atomic bomb, he reluctantly agreed to support his work on the “Super.”

The hydrogen bomb was at least one thousand times more powerful than the Hiroshima and Nagasaki atomic bombs. Oppenheimer questioned whether a hydrogen bomb was militarily desirable or morally justified. After the war, Oppenheimer and other eminent scientists advocated ending development of the hydrogen bomb.

Atomic Energy Commissioner Lewis Strauss joined Teller in favor of a hydrogen bomb that promised to make a “quantum jump” in the capacity of the US nuclear stockpile. Teller accused Oppenheimer of acting on “direct orders from Moscow.” With Strauss and Teller questioning Oppenheimer’s loyalty, President Eisenhower authorized an Atomic Energy Commission investigation.

Beginning in 1950, Congressman Joe McCarthy held hearings on suspected Communists who were allegedly infiltrating American government, universities, industry, and elsewhere. In this atmosphere, the AEC began its own three- week security hearing on Oppenheimer in April 1954.

The proceedings were riddled with unfair and illegal procedures, including wiretapping Oppenheimer’s private discussions with his attorney. Teller’s testimony was most damning: “If it is a question of wisdom and judgment as demonstrated by actions since 1945, then I would say one would be wiser not to grant clearance.”

The AEC voted 2-to-1 to remove Oppenheimer’s security clearance and sideline him from setting US nuclear weapons policies. It was not until December 2023 that the Department of Energy’s Secretary Jennifer Granholm vacated the 1954 decision.

Meanwhile, work on the H bomb continued. In 1951, Teller collaborated with Polish mathematician Stanislaw Ulam and successfully invented a new design for a hydrogen bomb. However, Teller refused to give Ulam the credit he deserved, saying dismissively, “I contributed; Ulam did not.”

In 1952, Teller and physicist Ernest O. Lawrence founded a new laboratory that would rival the Los Alamos laboratory. The Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory allowed Teller to pursue the hydrogen bomb with its full support. Teller became known as the “Father of the Hydrogen Bomb,”

Over the next decades, Teller was increasingly engaged in the politics of nuclear weapons defense. In the 1980s, he promoted the strategic defense initiative (known as “SDI,” or “Star Wars” to critics). Like his promotion of the hydrogen bomb in the early 1950s, Teller’s predictions for SDI were very optimistic and unproven. In Reagan’s words, the system would “give us the means of making nuclear weapons impotent and obsolete.” Unfortunately, making a reliable system would be, at best, decades away.

Apart from his scientific work, Teller could be charming and good company. He loved to play the piano, preferring bold pieces by Rachmaninoff and others. He read fairy tales broadcast on the Los Alamos radio for the children of the Manhattan Project. His grandson Astro Teller remembers playing chess and Go with him as a boy. The elder Teller was always determined to win. If he lost, he demanded an instant rematch.

Teller died in 2003 after a long life centered on nuclear weapons. Most believe that producer Stanley Kubrick was inspired by Teller when he created the title character for his 1964 film, “Dr. Strangelove or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb.”

Oppenheimer coming July 21, 2023

Be prepared for Christopher Nolan’s “Oppenheimer,” on July 21, 2023. After seeing the movie, Kai Bird, co-author of Pulitzer Prize-winning American Prometheus:The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer on which the movie is based, is “still recovering emotionally.” Unlike Nolan’s other movies, this one is “R” rated so that children under 17 must be accompanied by a parent or guardian.

Nolan said, ‘“I know of no more dramatic tale with higher stakes, twists and turns and ethical dilemmas. The finest minds in the country were in a desperate race against the Nazis to harness the power of the atom in World War II.”

As a producer, Nolan prefers real world environments and avoids the use of computer-generated imagery. For the movie Dunkirk, Nolan found real World War II ships for the film’s battle scenes. For Oppenheimer, Nolan recreated a mock nuclear weapon detonation in New Mexico. Kai Bird said the movie was “stunning.”

The Manhattan Project National Historical Park (MAPR) sites are planning special showings and complementary programming including at the SALA event center in Los Alamos. Oak Ridge’s premier will be at the Cinemark theater. After the show in Kennewick, WA, join one of the B Reactor tours at Hanford. Wherever you see the film, remember the extraordinary weather and explosions you are watching are not just special effects.

National History Day

Since 1974, students across the country have competed in the National History Day (NHD) contest. Run by a nonprofit in College Park, MD, this year a half-million students developed projects around the theme “Frontiers in History: People, Ideas, and Events.” Not surprisingly, a number of entries featured aspects of the Manhattan Project.

From June 10 to 15, 2023, the University of Maryland hosted over 2,600 students and 600 teachers (see photo, above). The national contest is the culmination of a year’s research and project creation, with preliminary competitions at local and state levels. The top students from all 50 states, Washington, DC, and US territories were invited to complete in the national contest which had more than 400 historians and judges.

One bonus was that Heather McClenahan, the former director of the Los Alamos History Museum, came to Washington, DC to be a judge. Now living in Las Cruses, NM, Heather enjoys working on Manhattan Project related projects including interpreting the Oppenheimer house in Los Alamos, below.