Nobel Prize-winning physicist Val Fitch recalled being awestruck by the world’s first nuclear test, the Trinity Test: “It’s hard to overstate the impact on the senses of something like that. First the flash of light, that enormous fireball, the mushroom cloud rising thousands of feet in the sky, and then, a long time afterwards, the sound. The rumble, thunder in the mountains. Words haven’t been invented to describe it in any accurate way.”

The Atomic Heritage Foundation (AHF) has launched a new “Ranger in Your Pocket” (www.RangerInYourPocket.org) online educational program on the history of the Trinity Site, where the test took place. The program features over thirty video vignettes with firsthand accounts from Fitch, Manhattan Project leaders General Leslie Groves, J. Robert Oppenheimer, George Kistiakowsky, and others. Veterans describe the fateful day of July 16, 1945, when the Manhattan Project ushered the world into the Atomic Age.

AHF has partnered with the White Sands Missile Range Historical Foundation on the project. In addition to being available online, the vignettes may also be shown in the White Sands Missile Range Museum, which is currently being expanded. The Trinity Site is open to tourists two days a year including on Saturday, October 6, 2018. This program will be a valuable resource for visitors to learn more about the Trinity Site and what they can see during their trip.

Darren Court, director of the White Sands Missile Range Museum, remarked, “The museum is pleased to have this program on the Trinity Site in time for the Open House on Saturday, October 6, 2018. In addition, it will be a great asset for visitors to the museum year round.”

Jim Eckles, who worked in the White Sands Missile Range Public Office for thirty years, stars as the leading expert on the Trinity Site. Beginning with the early history, Eckles explains that the site is near the notorious Jornada del Muerto road, or “Journey of the Dead Man.” Spanish colonizers gave the road the forbidding name because many settlers lost their lives to thirst, starvation, or attacks by members of the Apache tribes. Over the centuries, ranchers settled in the area and raised cattle, sheep, and other livestock.

During World War II, Manhattan Project scientists raced to design and build the world’s first atomic bombs, fearing Nazi Germany might develop one first. In early 1944, scientists at the laboratory at Los Alamos, NM, struggled to design a plutonium-based bomb. Fearing it might not work, they searched for a remote, isolated area to test it. After viewing several sites, they settled on a corner of the Alamogordo Bombing Range, 240 miles south of Los Alamos. Ranchers in the area had been forced to more off their land when the US Army Air Force leased it to create the Alamogordo Bombing and Gunnery Range in 1941.

During World War II, Manhattan Project scientists raced to design and build the world’s first atomic bombs, fearing Nazi Germany might develop one first. In early 1944, scientists at the laboratory at Los Alamos, NM, struggled to design a plutonium-based bomb. Fearing it might not work, they searched for a remote, isolated area to test it. After viewing several sites, they settled on a corner of the Alamogordo Bombing Range, 240 miles south of Los Alamos. Ranchers in the area had been forced to more off their land when the US Army Air Force leased it to create the Alamogordo Bombing and Gunnery Range in 1941.

In the “Ranger in Your Pocket” program, Manhattan Project veterans describe their uncertainty. They worried about whether the bomb would work at all, and if so, whether it would work too well. Physicist Emilio Segrè was assured by others that “there was no chance of igniting the atmosphere. But I’m enough of a physicist to know that you calculate everything, and then something happens that you never dreamed of.”

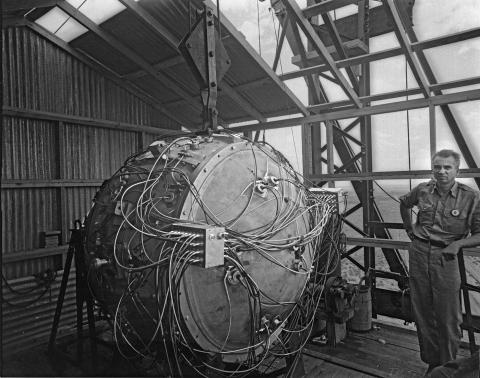

In the unrelenting desert heat, the preparations were especially intense as the deadline neared in mid-July 1945. The plutonium core was carefully assembled in a former bedroom of the Schmidt/McDonald Ranch House. Shirtless young men in shorts worked on the “Gadget” under a makeshift tent before the bomb was hoisted to the top of the 100-foot steel tower. Norris Bradbury, who succeeded Oppenheimer as director of the Los Alamos National Laboratory, explained, “My personal concern with the Trinity shot was to get that Gadget assembled up on top of the tower…I would not let anybody come up unless I was there, because I didn’t want anybody monkeying with it. I was responsible for that thing. Even inadvertently, somebody might brush against something.”

Army Corps of Engineers General Groves had ordered an enormous steel container dubbed “Jumbo” to be made as a precaution. If the bomb was a dud, Jumbo would contain the nuclear device and its precious plutonium. But by the time the test occurred, scientists were confident the “Gadget” would work and did not use Jumbo. Later, the Army set off explosives in Jumbo, trying to destroy it but only blowing off its ends. Visitors at the site today can see Jumbo’s remains.

-822x1024.jpg)

On July 16, 1945, a major thunderstorm postponed the test until 5:29 AM. For most of the scientists, the long vigil was nerve wracking. But the unflappable General Groves caught three or four hours of sleep. “We had about four hours to wait for the bomb there. The tents were flapping and there was a high wind. [James B.] Conant and [Vannevar] Bush were in the same tent with me. They said after, “How on earth did you sleep? You went right to sleep, and we stayed awake!”

The moment of detonation elicited various responses from eyewitnesses. Physicist Hans Courant evoked his emotional response to the fireball: “My hands got warm from the heat from the bomb, which just grew and grew, and then eventually started up into the sky. I had been sitting there and I thought, “Oh, my God.” It was terrible. Suddenly, I realized that next time there would be people under it. It never occurred to me. Well, it was also wonderful. It worked.”

Chemist William Spindel remembered: “It was the most shocking, enormous explosion that I had ever seen. It was the most intimidating minute I have ever spent. Seeing the terrible ball, growing and growing, enormous colors.” Chemist Lilli Hornig: “These sort of boiling clouds and color—vivid colors like violet, purple, orange, yellow, red, just everything. It was fantastic. And we were all kind of shaken up.” Val Fitch recalled remarking, “The war will soon be over.”

The “Ranger” program explores the legacy of the Trinity Test for New Mexico and the world today. In one vignette, historian Jon Hunner explains the chilling significance of the successful test: “Now humans have the ability to destroy the earth.” Eckles clarifies the source of the famous “trinitite” glass produced by the test, which tourists love to search for during visits to the site. The program also describes the possible health effects of radioactive fallout and the efforts of the Tularosa Basin Downwinders to receive compensation and recognition for their suffering.

The Atomic Heritage Foundation is very grateful to the White Sands Missile Range Historical Foundation, the New Mexico Intervention Fund of the National Trust for Historic Preservation, philanthropists Clay and Dorothy Perkins, and other private donors for their financial support of the project.