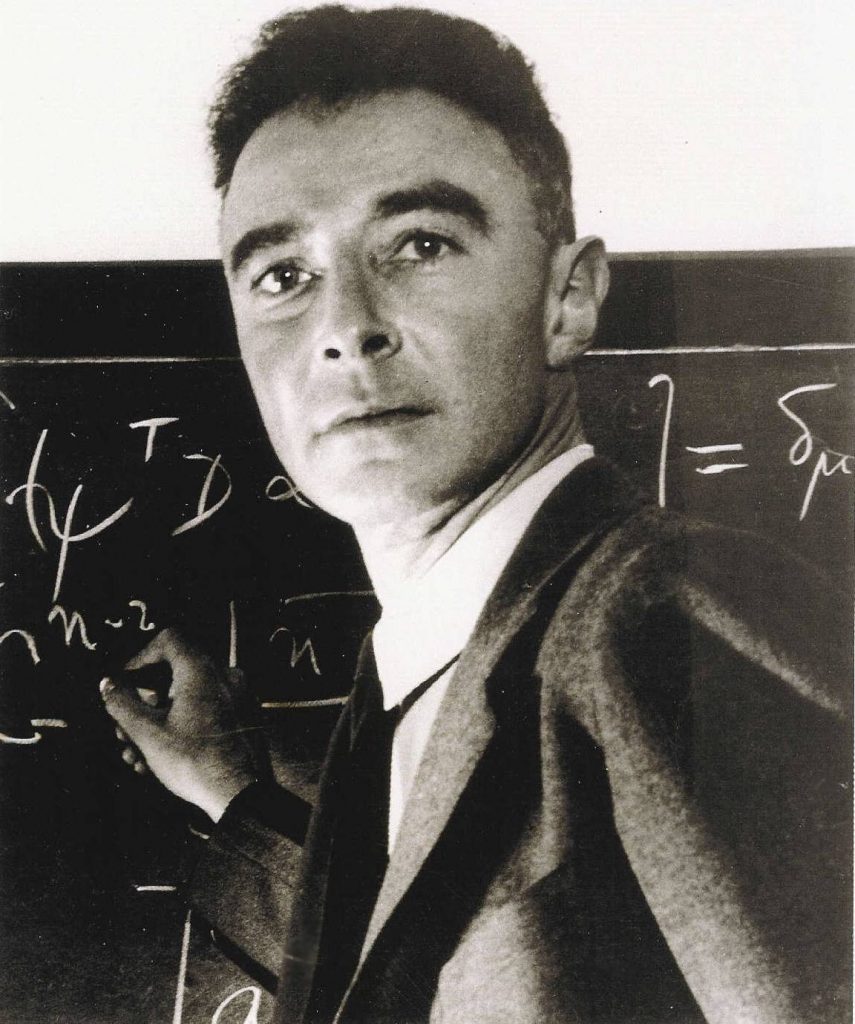

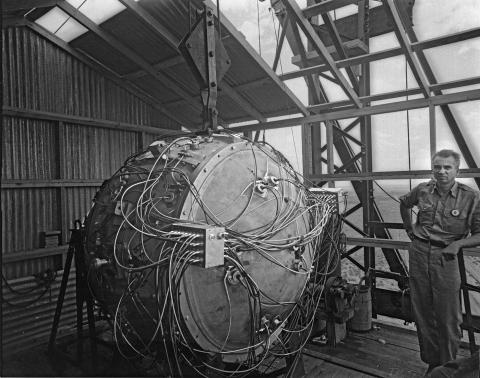

Doctor Atomic is an opera composed by John Adams with a libretto by Peter Sellars. The opera, which premiered in 2005, takes place in the weeks leading up to the Trinity Test, the first-ever detonation of a nuclear weapon. J. Robert Oppenheimer, director of the Los Alamos Laboratory, is the central character of the opera. Other historical figures involved in the Manhattan Project, including General Leslie Groves, Edward Teller, Robert R. Wilson, and Kitty Oppenheimer, are also represented.

Opera: A Background

The Encyclopedia Britannica defines opera as “a staged drama set to music in its entirety, made up of vocal pieces with instrumental accompaniment and usually with orchestral overtures and interludes.” Opera is a complex and collaborative art form. An operatic work begins with the composer, who writes the music, and the librettist, who writes the words. A performance of an opera requires an orchestra, principal singers, usually dancers and a chorus, and designers of the set, props, costumes, and lighting. Additionally, an opera needs a producer (or director) to coordinate the creative work, as well as administrative staff to take care of marketing, ticket sales, and other crucial functions. In short, producing an opera is a massive, and very expensive, undertaking. As such, opera has historically been an art form for the elite.

Drawing on existing musical and theatrical traditions in Western society, opera first began to emerge in late sixteenth-century Florence. Throughout the 1600s, the opera spread to other Italian cities, including Rome, Naples, and Venice. Opera grew more sensational in its plots, more extravagant in its sets and costumes, and more commercial as an enterprise. By the turn of the eighteenth century, opera had begun to spread to such countries as France, Germany, England, and Austria. In Europe, opera has continued to develop ever since with premieres of new works and revival productions of old ones, known in opera parlance as “repertory works.”

Opera grew popular among American elites in the nineteenth century, but the most frequently-performed works in the United States were those of the European master composers. After World War II, however, productions of new and inventive operas by American composers became more frequent, and these works grew in popularity among operagoers. This wave of American innovation in the opera has continued up through today.

The works of John Adams exemplify this trend. Even before Doctor Atomic, Adams had established himself as a prominent composer of contemporary American opera and classical music. His two previous operas, Nixon in China (1987) and The Death of Klinghoffer (1991), foreshadowed Doctor Atomic in that they both depicted recent historical events—respectively, President Nixon’s 1972 visit to China and the Achille Lauro hijacking in 1985. This represented a significant departure from the often-mythic subject matter of traditional operas, the start of a trend in recent opera toward subjects of contemporary political relevance. A 1995 New York Times article quotes Peter Sellars, director of the original productions of both of these works, as saying that “we’re watching opera move from being a decorative element for the wealthy to a socially engaged, active participant in the question of the founding of our society.”

Sellars went on to direct the original production of Doctor Atomic, which was also the first Adams opera for which he contributed the libretto. Since Doctor Atomic, the composer-librettist duo has gone on to write two more operas, A Flowering Tree (2006) and Girls of the Golden West (2017).

Creating Doctor Atomic

In 1999, Pamela Rosenberg, then-director of the San Francisco Opera, approached Adams in the hopes of commissioning an “American Faust” focusing on Oppenheimer and the Los Alamos story. Initially, Adams was lukewarm to the idea. He said at an Atomic Heritage Foundation symposium in 2006 that Faust seemed “very much a German or European myth, and that we Americans, we really have our own separate mythology.” Despite his lack of enthusiasm for the Faust aspect, Adams did see the dramatic potential in the atomic bomb, which he characterized as the “ultimate American myth” in its own right. He agreed to go forward with the project.

In 1999, Pamela Rosenberg, then-director of the San Francisco Opera, approached Adams in the hopes of commissioning an “American Faust” focusing on Oppenheimer and the Los Alamos story. Initially, Adams was lukewarm to the idea. He said at an Atomic Heritage Foundation symposium in 2006 that Faust seemed “very much a German or European myth, and that we Americans, we really have our own separate mythology.” Despite his lack of enthusiasm for the Faust aspect, Adams did see the dramatic potential in the atomic bomb, which he characterized as the “ultimate American myth” in its own right. He agreed to go forward with the project.

Alice Goodman, librettist for Nixon in China and The Death of Klinghoffer, was slated to collaborate again with Adams on Doctor Atomic. However, she ultimately decided to leave the project, so Peter Sellars stepped in. Rather than writing original material, Sellars made the unconventional decision to assemble a libretto from a variety of sources. The libretto mixed direct quotations of Manhattan Project figures—as recorded in letters, declassified documents, and memoirs—with passages from various other texts, including the Bhagavad Gita, a Tewa Pueblo lullaby, and poetry by the likes of John Donne, Charles Baudelaire, and Muriel Rukeyser.

Sellars and Adams have both justified the inclusion of poetry in the libretto on account of Oppenheimer’s well-known poetic disposition. As a Harvard student, Oppie was known to write and exchange sonnets with his friends as a way to relax. In a 1962 letter to General Leslie Groves, he references having had in mind Donne’s sonnet, “Batter my heart, three-person’d God” when naming the Trinity Test. In Doctor Atomic, Adams and Sellars set the sonnet to music as a soliloquy for Oppenheimer at the end of Act I, on the eve of the Trinity Test. In a panel discussion supplementing the original San Francisco production, Sellars recalls finding in his research that Kitty and Robert Oppenheimer, frustrated by the secrecy required for life in Los Alamos, would often communicate with each other in code through Baudelaire quotes. Thus, Sellars and Adams chose to use a Baudelaire poem as the text for a love scene between the two.

One issue that Sellars and Adams encountered in creating Doctor Atomic was the bias of representation in the documentary record, which pays careful attention to the high-ranking white men working on the Manhattan Project, but provides little to no information on the lives of the women and racial minorities who were also present in Los Alamos. This bias permeates the collective cultural understanding of the Manhattan Project as well. As John Adams put it, “The narrative is really one of guys, the brilliant young scientists and the Army, and it’s easy to overlook the fact that there were many women here.”

In an effort to expand this narrative, Adams and Sellars included the characters of Kitty Oppenheimer and Pasqualita. In Doctor Atomic, Pasqualita is the Tewa nursemaid for Oppenheimers. Although there is no documentation of the Oppenheimer family having such a maid, many Tewa women were employed in domestic work in Los Alamos, so the inclusion of this character is plausible. In fact, her namesake was a real Pueblo woman who helped the McMillan family around the house in Los Alamos, and whom Elsie McMillan remembers fondly.

Where the archival record has left gaps, Sellars and Adams have filled them in with poetry. Lacking direct quotations from Kitty Oppenheimer, Sellars chose to have her speak through the poetry of Muriel Rukeyser, a passionate, socially conscious poet and contemporary of the Oppenheimers. Sellars gives Pasqualita the text of a traditional Tewa lullaby as she sings the Oppenheimers’ baby to sleep on the eve of the Trinity Test.

Synopsis

Synopsis

The opera begins in June of 1945, a few weeks before the Trinity Test. Since Germany’s surrender in May, a group of scientists working on the bomb have begun to harbor misgivings about the planned use of the bomb against Japan. Robert Wilson circulates a petition intended for President Truman. Oppenheimer stops them, having recently returned from Washington with the news that the decision has been made to use the bomb. Additionally, the chosen strategy will target war plants in urban areas, surrounded by many civilians’ houses, with the goal of creating as much fear as possible.

In the next scene, Kitty and Robert reflect in their home on their love for each other and the moral nature of war. For the third scene, we move forward in time to July 15, 1945: the eve of the Trinity Test. An apprehensive air hangs about the stage as an electrical storm rages and General Groves grows increasingly frustrated. Act I ends with Oppenheimer reflecting on what is to come the next morning, and his role in the development of the bomb.

Act II starts back in the Oppenheimers’ home in Los Alamos, where Kitty and Pasqualita anxiously wait for signs of the explosion two hundred miles away. The second scene moves back to the test site around midnight before the test. Despite concerns over the escalating weather, General Groves orders that the test commence as scheduled. The men nervously wait in the storm until the sky clears ten minutes before the test. Time seems to stretch as suspense grows in the final moments leading up to the bomb. Once the countdown has finished, there is, according to the stage directions, “a mournful silence and the beginning of a new era.”

Doctor Atomic in the World

In addition to the original production at the San Francisco Opera in 2005, other notable productions of Doctor Atomic have been mounted at the Lyric Opera of Chicago in 2007, Die Nederlandse Opera in Amsterdam in 2007, the Metropolitan Opera in New York City in 2008, the Curtis Opera Theatre in Philadelphia in 2017, Barbican Hall in London in 2017, and the Santa Fe Opera in 2018.

Critics have mostly responded positively to Adams’s score. Alex Ross, classical music critic for the New Yorker, praised it in 2008 as “not only an ominous score but also an uncommonly beautiful one.” A 2017 review in the Philadelphia Inquirer commended Adams’s score for its “stretches of greatness, particularly in the first act, where the music plays with the tension between the warmth of humanity and science’s realization that for the first time it has humanity’s end in sight—and it was science itself that cleared the path.”

Tim Page, writing for the Washington Post in 2005, applauded Adams’s musical eclecticism, declaring that “Adams has begun to absorb the spectrum of musical history, the way past composers absorbed theory, counterpoint and harmony, and, by the force of will, made it distinctly his. To adapt a familiar but useful metaphor, “The trees in Doctor Atomic may not always be recognizably ‘Adams,’ but he owns the forest.”

Critical reception of Sellars’s libretto has been more mixed. While Page’s Washington Post review praised the libretto as “protean and dramatically vital for most of the evening,” a New York Magazine piece called it “an inelegant thing, lurching between documentary and mythic modes.” Another review in Slate Magazine called the libretto “pedestrian, speechifying, and painfully simplistic (when not embarrassingly schlocky as in the ‘love scenes’).”

Some critics have found the opera’s treatment of Oppenheimer’s moral attitudes toward the bomb to be simplistic. Ron Rosembaum wrote in Slate that he thought Doctor Atomic reduced Oppenheimer’s moral dilemma to “Do I want to succeed in building a bomb that could be used to kill 100,000 people at a time, or is that bad?”, not sufficiently taking into account Oppenheimer’s knowledge that many American and Japanese soldiers would likely die if Japan were invaded.

It is important to remember that the Oppenheimer of Doctor Atomic is not the man himself, but Oppenheimer as interpreted by and mediated through Adams and Sellars. This is true of all of the real-life historical figures portrayed in Doctor Atomic. Even when speaking—or singing—their own archivally recorded words, the characters of the opera should not be considered exact replicas of their historical counterparts in a given moment.

In an interview with New Mexico PBS, Sellars acknowledged that “a lot of what some of these gentlemen thought at the end of their lives has made it into the libretto.” Retrospective reflections have the gift of hindsight, and many scientists came to feel differently about the bomb in later years than they might have while working on the Manhattan Project. Thus, depicting these later thoughts as occurring in 1945 does not offer a strictly accurate picture of what the scientists may actually have been feeling in the weeks leading up to the Trinity Test. However, it may help the audience grasp the broader significance of the narrow sequence of events chronicled by the opera. A well-researched work of historical fiction, Doctor Atomic does the important work of engaging with and inviting moral contemplation of the history of the atomic bomb.