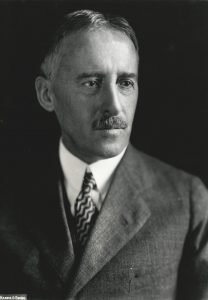

As the Manhattan Project neared its first atomic test, there was a growing sentiment among project leaders that an advisory committee to make recommendations on nuclear energy should be created. In response to these concerns, in May 1945 Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson, with the approval of President Harry Truman, established the Interim Committee. The committee was so named because it was an interim, or temporary body, that would last until a more formal organization dealing with nuclear issues was created. Its official function was “to study and report on the whole problem of temporary war controls and later publicity, and to survey and make recommendations on post war research, development and controls, as well as legislation necessary to effectuate them” (Norris 658).

The Target Committee

In the early spring of 1945, prior to the creation of the Interim Committee, General Leslie Groves established the Target Committee to provide military recommendations on how to use of the atomic bomb. It included Manhattan Project scientists William Penney, who worked on “the size of the bomb burst, the amount of damage expected, and the ultimate distance at which people would be killed” and John von Neumann, who worked on computations (Rhodes 628). Their recommendations would become paramount as the Interim Committee made its final decisions.

During this time, there were six options under consideration (Norris 379):

- Use as a tactical weapon to assist in the invasion of Japan

- Use as a demonstration before observers

- Use as a demonstration against a military target

- Use against a military target

- Use against a city with warning

- Use against a city without warning

The Target Committee also worked to establish a list of potential target cities. They had to be “important targets in a large urban area of more than three miles diameter… capable of being damaged effectively by blast” and “likely to be unattacked by next August” (Rhodes 632). According to Groves, the reason for this last criterion was “to enable us to assess accurately the effects of the bomb” (Rhodes 627). This would prove to be difficult, however, as they had to coordinate with the U.S. Air Force, which recently intensified its bombing campaign against many Japanese cities.

One of the principal arguments in favor of dropping the bomb was that it could force a Japanese surrender without a ground invasion. To do so, however, would mean that the bomb had to both demonstrate military superiority and also break the will of the Japanese to continue waging war. Therefore, in choosing the list of cities, the Target Committee asserted “that psychological factors in the target selection were of great importance. Two aspects of this are (1) obtaining the greatest psychological effect against Japan and (2) making the initial use sufficiently spectacular for the importance of the weapon to be internationally recognized when publicity on it is released.” This second aspect was particularly important for demonstrating American military power to the Soviet Union, which would soon occupy most of Eastern Europe and was also preparing to invade Japan.

On May 10, the Target Committee sent a set of recommendations to General Groves establishing Kyoto, Hiroshima, Yokohama, Kokura Arsenal, and Niigata as the primary targets of the bomb. The idea of bombing the Japanese emperor’s palace was considered, but ultimately deemed militarily unfeasible. Kyoto and Hiroshima were considered high priority “AA” targets. The Target Committee noted that “from the psychological point of view there is the advantage that Kyoto is an intellectual center for Japan and the people there are more apt to appreciate the significance of such a weapon as the gadget” while Hiroshima was “an important army depot and port of embarkation in the middle of an urban industrial area.”

Nevertheless, as Groves would later remember, Secretary Stimson was adamantly against the inclusion of Kyoto on the list of targets. “He immediately said: ‘I don’t want Kyoto bombed.’ And he went on to tell me about its long history as a cultural center of Japan, the former ancient capital, and a great many reasons why he did not want to see it bombed” (Rhodes 640). By the time of the Trinity Test, the list of preferred cities had been refined to just three: Hiroshima, Yokohama, and Kokura Arsenal. Nagasaki would not be added to the list until the end of July.

Establishing the Interim Committee

The Interim Committee would convene eight times beginning on May 9, 1945. Unlike the Target Committee, the Interim Committee consisted almost entirely of civilians: Stimson as chairman, his assistant George Harrison as the alternate chairman, Undersecretary of the Navy Ralph Bard, Assistant Secretary of State of Economic Affairs William Clayton, Vannevar Bush, James Conant, Karl Compton, and James Byrnes as a representative of President Truman.

In addition to these eight representatives, the Interim Committee also established the Scientific Panel consisting of Manhattan Project leaders Arthur Compton, Ernest Lawrence, J. Robert Oppenheimer, and Enrico Fermi. Although their scientific expertise was certainly useful, another reason for creating the Scientific Panel was to appease the growing discontent among Manhattan Project scientists over possible military use of the bomb, exemplified in the Franck Report and the Szilard Petition. The four scientists were told they could “feel free to tell their people” that the committee had met and that they had been given “complete freedom to present their views on any phase of the subject” (Bird and Sherwin 297).

General George Marshall and General Groves were not officially part of the committee, but attended several meetings. According to Groves, “The purpose of the establishment of the Interim Committee was not so much to obtain its advice but rather to make certain that the American people as well as the leaders of other nations would realize that the very important decision as to the use of the bomb were not made by the War Department alone but rather that [they] were decisions reached by a group of individuals well removed from the immediate influence of men in uniform” (Norris 389).

Concerns over Post-War Control

At the committee’s first meeting on May 9, Stimson suggested that the bomb should be recognized not “as a new weapon merely but as a revolutionary change in the relations in the universe,” the implications of which “went far beyond the need of the present war” because it could become “a Frankenstein which would eat us up” (Bird and Sherwin 293). When asked about the future development of nuclear weapons, Oppenheimer asserted his belief that the “super bomb” (what would become the hydrogen bomb) was possible, while Lawrence recommended that “a sizable stockpile of bombs and material should be built up” (Bird and Sherwin 294).

Oppenheimer also suggested that there should be a “free exchange of information” between countries on the peaceful uses of atomic energy. Surprisingly enough, this view was shared by General Marshall, who asserted that because “Russia had always been friendly to science” it could be a starting point for future cooperation. Marshall even suggested that they invite two prominent Soviet scientists to witness the Trinity Test (Bird and Sherwin 295). Nevertheless, the committee also raised “the question of paramount concern… the attitude of Russia” (Norris 390). In the end the decision not to share atomic secrets may have contributed to the arms race during the Cold War.

The Decision

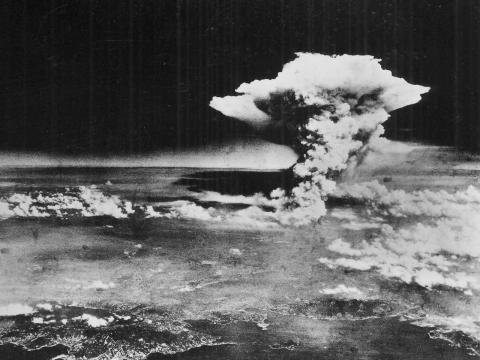

Despite the fact that from the beginning, according to Arthur Compton, it seemed “a foregone conclusion that the bomb would be used” (Norris 391), it took until June 1 for the committee to recommend use of the bomb. According to notes from this meeting, “the Committee agreed… that the Secretary of War should be advised that, while recognizing that the final selection of the target was essentially a military decision, the present view of the Committee was that the bomb should be used against Japan as soon as possible; that it be used  on a war plant surrounded by workers’ homes; and that it be used without prior warning.”

on a war plant surrounded by workers’ homes; and that it be used without prior warning.”

The Scientific Panel was also given the opportunity to make its own final recommendation independently from the rest of the committee. The scientists concluded that although “the opinions of our scientific colleagues on the initial use of these weapons are not unanimous… we can propose no technical demonstration likely to bring an end to the war; we see no acceptable alternative to direct military use.” The Scientific Panel also recommended “that before the weapons are used not only Britain, but also Russia, France, and China be advised that we have made considerable progress in our work on atomic weapons, that these may be ready to use during the present war, and that we would welcome suggestions as to how we can cooperate in making this development contribute to improved international relations.” Although this type of international cooperation would not come to pass, President Truman did choose to hint at the existence of the bomb at the Potsdam Conference in July.

Legacy

After the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the Scientific Panel of the Interim Committee was asked to issue a set of recommendations on the future of atomic energy. In a letter to Secretary Stimson, they concluded among other observations “that weapons quantitatively and qualitatively far more effective than now available will result from further work on these problems” but that “we have been unable to devise or propose effective military counter-measures for atomic weapons.” For this reason, the four scientists offered this sobering recommendation on the future of national security:

“We believe that the safety of this nation – as opposed to its ability to inflict damage on an enemy power – cannot lie wholly or even primarily in its scientific or technical prowess. It can be based only on making future wars impossible. It is our unanimous and urgent recommendation to you that, despite the present incomplete exploitation of technical possibilities in this field, all steps be taken, all necessary international arrangements be made, to this one end.”

The Interim Committee was officially disbanded following the Atomic Energy Act of 1946, which established the Atomic Energy Commission as the civilian institution responsible for all nuclear affairs.