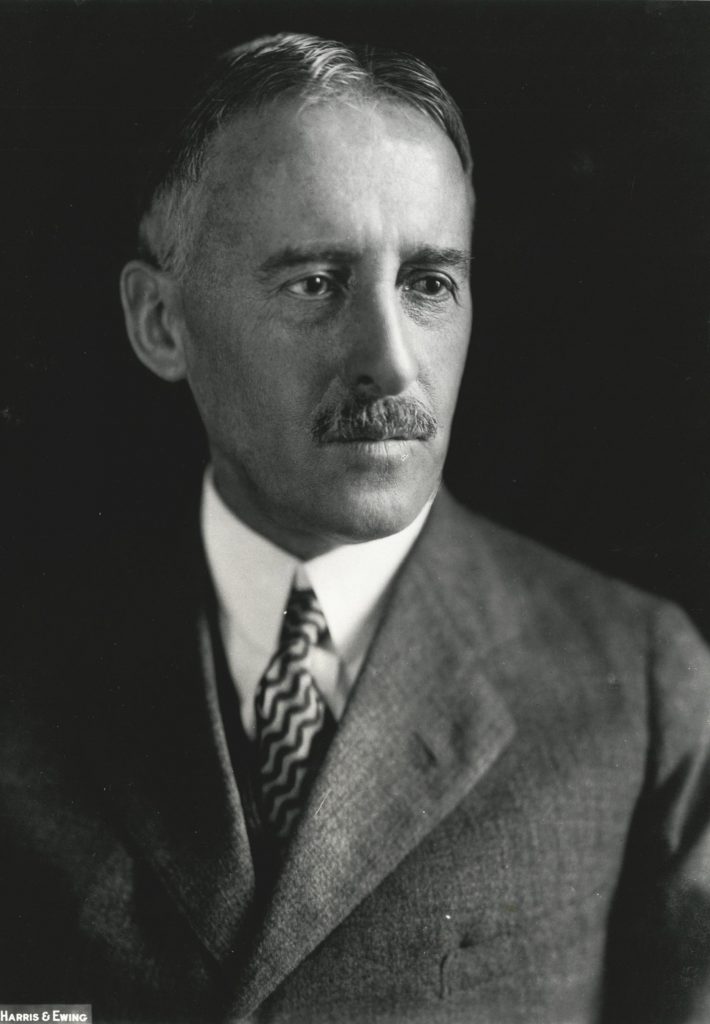

As Secretary of War under Presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry Truman, Henry L. Stimson (1867-1950) oversaw the entire Manhattan Project, and was responsible for appointing key project leaders and authorizing project construction sites across the US.

By the time Stimson became Secretary of War under Roosevelt, scientific processes behind the atomic bomb had been researched for nearly a decade, but no formal proposals suggesting a US organization to research and construct a nuclear weapon had yet been made. In 1941, President Roosevelt appointed Stimson, along with Vice President Henry Wallace, Army Chief of Staff George Marshall, and scientists Vannevar Bush and James B. Conant to a Top Policy Group dedicated to exploring nuclear technology and policy. As the potential strength and importance of nuclear weapons grew clearer, the Top Policy Group evolved into a separate entity dedicated to producing the atomic bomb–the Manhattan Project–with Stimson as its head.

Beginning in late 1942, Stimson authorized project sites and remained informed of all program ventures. Stimson also secured the necessary money and approval from Roosevelt and from Congress, and made sure the Manhattan Project had the highest priorities. He appointed General Leslie Groves to oversee all site planning, scientific research, and construction. His choice of Groves to lead the project ultimately proved of great importance, as Groves’ decisive, efficient, and blunt manner swiftly moved the project towards completion in 1945.

While Stimson grew ever older and more frail under Roosevelt’s administration–he was seventy-three at the time of his appointment as War Secretary–he refused to retire from the job, confiding to Groves that the Manhattan Project was in fact the only reason he stayed on. His devotion to the project spoke to his belief that the atomic bomb was of utmost importance to the US war effort.

Views on the Atomic Bomb

Although Stimson understood little of the science behind the bomb, he understood the complicated political and military implications the creation of the bomb would have on future international order. His dislike of what he viewed as the unethical war practices of city bombing and merciless attacks on civilians made him unwilling to use the bomb on Japanese cities, immediately rejecting Groves’ first suggestion to bomb Kyoto, a city he revered as the country’s ancient cultural hub. Ever careful with nuclear technology’s ability to irrevocably change international politics, Stimson also hesitated to support the dropping of the bomb without first warning Japan of its existence.

After Roosevelt’s death in 1945, Stimson, under the approval of now-President Truman, established The Interim Committee to discuss nuclear issues. The committee voted to use atomic bombs on Japan without prior warning. Despite Stimson’s doubts, however, he ultimately defended the use of the bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki after the attacks had been executed.