National Academy of Sciences Report

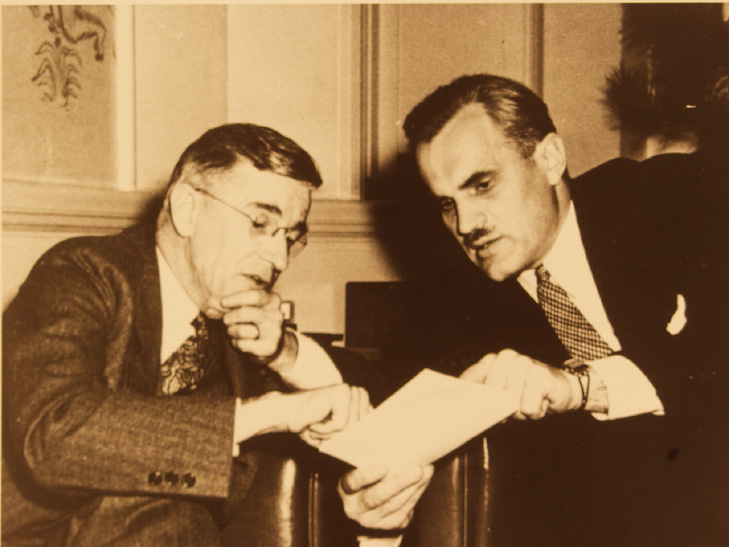

Vannevar Bush forwarded the final report of the National Academy of Sciences, which “agreed with the essence of The MAUD Report from Britain that an atomic bomb WAS feasible,” to the President on November 27, 1941. Roosevelt did not respond until January 19, 1942. By the time FDR responded, Bush had already set the wheels in motion. He put Edgar V. Murphree, a chemical engineer with the Standard Oil Company, in charge of a group responsible for overseeing engineering studies and supervising pilot plant construction and any laboratory-scale investigations. Next he appointed Harold Urey, Ernest Lawrence, and Arthur Compton as program chiefs.

Urey, located at Columbia, was put in charge of research on the diffusion and centrifuge methods of isotope separation as well as studies into the use of heavy-water as a moderator. Lawrence, at Berkeley, took charge of electromagnetic and plutonium responsibilities. Compton, at the University of Chicago, would run the chain reaction and weapon theory programs.

Top Policy Group

Bush’s responsibility was to coordinate engineering and scientific efforts and make final decisions on recommendations for construction contracts. In accordance with the instructions he received from Roosevelt, Bush removed all uranium work from the National Defense Research Committee (NDRC). From this point forward, broad policy decisions relating to uranium were primarily the responsibility of the Top Policy Group – Vannevar Bush, Vice President Henry Wallace, Secretary of War Henry Stimson, and Army Chief of Staff George C. Marshall.

A high-level conference convened by Vice President Wallace on December 16, 1941 put the seal of approval on these arrangements. Two days later, the S-1 Committee allocated $400,000 to Ernest Lawrence to continue his electromagnetic work.

With the United States now at war and with the fear that the American bomb effort was behind that of Nazi Germany, a sense of great urgency permeated the federal government’s scientific enterprise. Even as Bush tried to fine-tune the organizational apparatus, new scientific information poured in from laboratories to be analyzed and incorporated into planning for the upcoming design and construction phase.

By spring of 1942, as American naval forces slowed the Japanese advance in the Pacific with an April victory in the battle of the Coral Sea, the situation had changed from one of too little money and no deadlines to one of a clear goal, plenty of money, but too little time. The race for the bomb was on.

[The text for this page was taken from the U.S. Department of Energy’s official Manhattan Project history: F. G. Gosling, The Manhattan Project: Making the Atomic Bomb (DOE/MA-0001; Washington: History Division, Department of Energy, January 1999), 9-10.]