After World War II, the tension between communist and democratic forms of government strained relations between the Soviet Union and the United States and provided the ideological underpinnings of the Cold War. These tensions almost boiled over into full on conflict several times, especially as nuclear arms proliferation and testing advanced rapidly during the late 1950s and early 1960s. Both nations found it critical to expand their spheres of influence, largely by promoting leadership in the “Third World” that would be sympathetic to their causes. Arguably more important, however, was the ability to have friendly governments that could be used as allies to fight conventional wars or provide bases for the placement of nuclear warheads in the case of nuclear warfare. By using both diplomatic and military power, the United States and the Soviet Union attempted to carve out areas that could be utilized as staging grounds against one another.

The African continent, especially the southern and central portions, proved to be fertile grounds for these kind of interventions. Colonial powers in the region such as England, Portugal, Germany, and Belgium had started declining in power due to the tremendous costs associated with World War II. As many colonies pursued struggles for independence, the United States, Soviet Union, and China attempted to fill the power vacuums with money and arms. Skirmishes and full blown wars would occur as a result, as the two superpowers engaged in proxy wars that would kill many tho usands. The reverberations from these conflicts would further destabilize the region for years to come, leading to more wars, cases of genocide, and severely dysfunctional economies, the scars of which can still be seen today. While proxy wars occurred across the globe — from Central and South America, to parts of Asia — this article focuses on the proxy wars that occurred in the central, eastern, and southern portions of Africa.

usands. The reverberations from these conflicts would further destabilize the region for years to come, leading to more wars, cases of genocide, and severely dysfunctional economies, the scars of which can still be seen today. While proxy wars occurred across the globe — from Central and South America, to parts of Asia — this article focuses on the proxy wars that occurred in the central, eastern, and southern portions of Africa.

Congo Crisis (1960-1965)

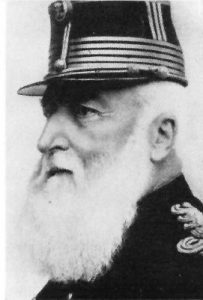

The Congo Crisis was a period of social, political, and military upheaval in the newly formed Republic of the Congo-Léopoldville (present day Democratic Republic of the Congo, formerly Zaire). Congo had been a Belgian territory since the 1880s. It was first privately owned by King Leopold II (right) and referred to as the Congo Free State before being renamed the Belgian Congo after it was taken over by the Belgian government. Under Belgian rule, life for the Congolese was miserable, with millions dying of starvation, disease, and poor working conditions.

Resistance began in the 1950s and culminated with a declaration of independence in June of 1960. Formally broken off from Belgium, the Republic of the Congo-Léopoldville was tasked with forming a government and quelling regional and tribal strife from within. These issues were exacerbated by a poor economy and years of destabilization. The Congolese power trio of Patrice Lumumba, Joseph Kasa-Vubu, and Joseph-Désiré Mobutu (later renamed Mobutu Sese Seko) faced challenges almost immediately. Sectarian violence and lawlessness had broken out during the first several weeks of independence, mainly between several tribal groups vying for power. Dozens of European nationals had been slaughtered as a result, causing the Belgian government to send troops back into the Congo to escort Belgian citizens back to Europe.

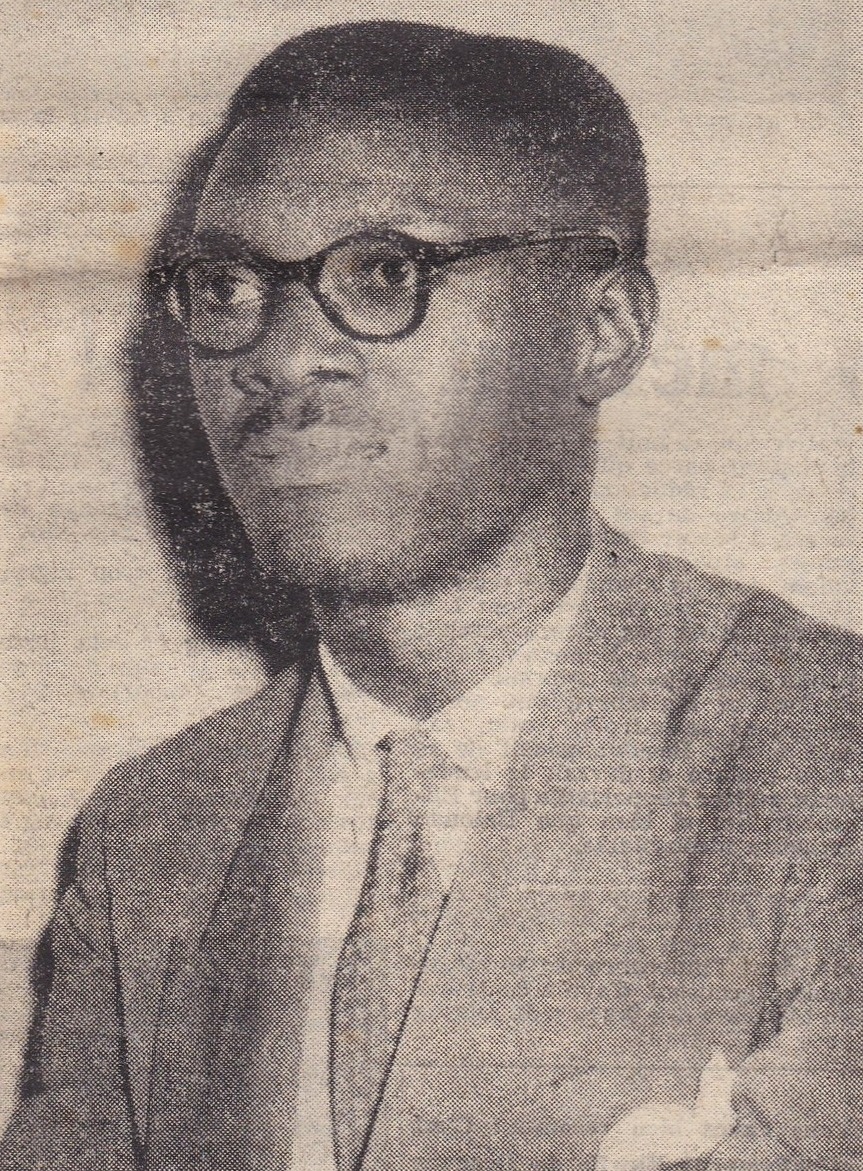

Under Lumumba (left), who became the first Prime Minister, power was consolidated and centralized in the capital of Léopoldville. The government developed an increasingly nationalist and communist tone, suppressing opposition parties and jailing their leaders. This caused the Katanga province, under the leadership of Moïse Tshombe, to secede. Tshombe was a relatively pro-Western leader and an enticing ally for the United States, which grew increasingly concerned with events in the Congo. The Soviet Union, too, saw opportunity in Lumumba, and the ground was set for a proxy war that would last five years. The main concern for both nations was not the wellbeing of the Congolese people or even financial gain. Rather, both nations were worried that the rich uranium mines in the southern areas of the Congo would come under the other’s control. While both the United States and the Soviet Union had uranium deposits of their own, the uranium located in the Congo was extremely valuable given its high quality. In fact, a majority of the uranium used in the “Little Boy” atomic bomb came from the Congolese mines.

Under Lumumba (left), who became the first Prime Minister, power was consolidated and centralized in the capital of Léopoldville. The government developed an increasingly nationalist and communist tone, suppressing opposition parties and jailing their leaders. This caused the Katanga province, under the leadership of Moïse Tshombe, to secede. Tshombe was a relatively pro-Western leader and an enticing ally for the United States, which grew increasingly concerned with events in the Congo. The Soviet Union, too, saw opportunity in Lumumba, and the ground was set for a proxy war that would last five years. The main concern for both nations was not the wellbeing of the Congolese people or even financial gain. Rather, both nations were worried that the rich uranium mines in the southern areas of the Congo would come under the other’s control. While both the United States and the Soviet Union had uranium deposits of their own, the uranium located in the Congo was extremely valuable given its high quality. In fact, a majority of the uranium used in the “Little Boy” atomic bomb came from the Congolese mines.

After being denied Western aid to control rebel factions in the south of Congo, Lumumba turned to the Soviets, who provided him with weapons and military advisors. This decision worried officials in the United States, who now believed the budding nation would officially turn communist. Doing so would provide Moscow with crucial uranium deposits, while depriving the United States of their most prosperous overseas mines.

In a backchannel coup, United States military advisors helped Mobutu (right) and Belgian operatives overthrow Lumumba.[1] Lumumba was then arrested and transported to Katanga, where he and several other of his supporters were summarily executed. The United States provided further aid to Mobutu, who would rule the country with an iron fist until 1997.,_Bernhard_en_Mobutu,_Bestanddeelnr_926-6037-300x295.jpg)

The Congo Crisis provided a look at foreign policy by both the Soviet Union and United States on the African continent for the next thirty years. Neither side was willing to engage each other directly with military force, but both were willing to send aid, weapons, and advisors to support their respective regimes. The Congolese conflict and later proxy wars focused on physical resources, but were also fought because of political ideology, economics, and geographic strategy.

Ogaden War (1977-1978)

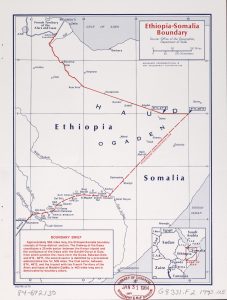

The Ogaden War was an eight-month long military engagement between the Provisional Military Government of Socialist Ethiopia (Derg) and the Somali Democratic Republic, supported by the Western Somali Liberation Front (WSLF). The conflict had its roots in territorial partitioning following the conclusion of World War II and the independence of Somalia from Italy and Great Britain in 1960. The Ogaden War was important in the context of the Cold War not because there was direct conflict between Soviet and American backed forces. Rather, the lack of American intervention on the part of the Somali regime, and the public fallout from President Jimmy Carter’s hesitancy to confront communist aggression, led to the gradual decline of détente between the United States and the Soviet Union.

Partitioning of the Horn of Africa stranded many ethnic Somalis in the neighboring countries of Ethiopia, Kenya, Djibouti, and Eritrea. The Haud, a valuable grazing area for nomadic communities, was located in the Ogaden. Legally a part of Ethiopia, the Ogaden was home to a majority Somali population. The Somalis were initially granted autonomy under British colonial rule, but this right was revoked when the British left and Ethiopia claimed sovereignty over the region. Almost immediately, the WSLF was formed and began a campaign of guerilla warfare against Ethiopian forces.

Less than ten years after being declared a sovereign nation, Somalia underwent a military coup which saw General Mohamed Siad Barre ascend to power. After declaring himself president, Barre established the Supreme Revolutionary Council, a communist junta which dissolved the Supreme Court and suspended the Constitution. Soviet funding to Somalia, which started in 1963, steadily increased. The goal of Soviet aid was to eventually establish a naval base at Berbera; doing so would enable the Soviets direct access to the Gulf of Aden and the Red Sea, in turn making sea trade with the oil-rich Arab nations to the north easier.

Ethiopia, to the west of Somalia, had been one of the only African nations which was never colonized (it was occupied by fascist Italy from 1936-1941). Following the end of the Solomonic dynasty, which saw Emperor Haile Selassie overthrown and replaced by the Marxist-Leninist Derg, Ethiopia descended into a political chaos for several years. General stability returned when Mengistu Haile Mariam took total control over the Derg in 1977.

Seeing an opportunity to retake the Ogaden and cement the support of his newly formed government, Barre (below right) aligned with WSLF forces and invaded the Ogaden in July of 1977. In one month, Barre’s forces had seized 60-70% of the Ogaden and seemed poised for a military victory. At this point, both sides were still backed by the Soviet Union and were using Soviet funds and arms to fight one another. However, the Soviet Union decided to shift primary support from Somalia to Ethiopia. Weapons, money, 1,500 Soviet advisors, and 15,000 Cuban troops arrived in the Ethiopian countryside in an attempt to stop the Somali offensive, which it did emphatically.

Barre immediately denounced the Soviet Union, and broke relations with every communist nation besides China and Romania. He then removed all Soviet diplomats in the country in an effort to draw in Western support. Barre was quoted as saying the United States needed to “fulfill its moral responsibility to Somalia” with more than just words.[2] Although the United States shifted in support of Somalia monetarily, the incursion into the Ogaden was denounced by American leadership as provocative, and no ground forces or advisors were committed to Barre.[3]

President Carter believed the issue should be resolved regionally, rather than internationally. With the memory of Vietnam still fresh, he did not want to overcommit in a distant conflict, nor did he want to upset the delicately balanced détente which had existed since the Cuban Missile Crisis. Carter repeatedly asked Soviet officials, such as Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko, to disengage from the conflict and allow it to be solved diplomatically. His wishes, however, we never met, and Cuban and Soviet forces drove the Somali National Army back across the Ogaden.

The Ogaden War ended in a rout and by March of 1978 all Somali forces had withdrawn from Ethiopian territory. The war spawned hardship in both countries, and each underwent brutal civil wars (Somalia’s continues to this day). In the context of the Cold War, the Ogaden conflict appeared a victory for the communist cause. The American public, and some members of Congress and Carter’s own cabinet, disagreed with the actions (or lack thereof) he took to help the Somalis. Many analysts believe that the conservative wave in the 1980 presidential election was due in large part to President Carter’s foreign policy mishaps, one of which, at least in the public’s opinion, occurred in the Ogaden.[4]

The Soviets were emboldened by their success and attempted to occupy Afghanistan in 1980. A final break in detente resulted, and the United States and Soviet Union entered a second phase of the Cold War.

Angolan Civil War (1975-2002)

The Angolan Civil War was a prolonged conflict in the southwestern African nation that spilled into several nearby countries, including the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Namibia. The conflict was fought along ethnic and political lines but included foreign intervention from the United States, the Soviet Union, China, Cuba, and South Africa. It is the best example of a true Cold War proxy war on the African continent, and its early years would ultimately shape foreign policy in southern Africa for subsequent conflicts.

The war began following the withdrawal of Portuguese forces following the Angolan War of Independence. 1974-1975 became known as the Angolan Crisis, as the power vacuum that had been created in the newly formed nation gave way to fighting between several military and political factions. Three parties existed: The Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA), which was Marxist in nature and supported by the Soviet Union and Cuba; the National Front for the Liberation of Angola (FNLA), which was backed by the United States; and the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA), which broke from the FNLA and was aided by China to counter Soviet assistance to the MPLA. The MPLA was led by Agostinho Neto, the FNLA by Holden Roberto, and the UNITA by Jonas Savimbi.

By mid-1975, the MPLA had forced FNLA and UNITA — which soon after signed a treaty of alignment with one another — south toward the Angola-South West Africa (modern-day Namibia) border. The Apartheid government of South Africa, hoping to limit leftist activity in the region, approved the use of ground forces bolster the retreating FNLA and UNITA forces and prevent a possible rout. Following a brief offensive under the newly formed coalition, the Soviet Union and Cuba doubled down on their defense of the MPLA government. The Soviets amped up their economic aid, while the Cubans initially committed about 15,000 ground troops to the region, a number that rose to nearly 36,000 within the year. The United States responded by furthering aid of their own to the UNITA and FNLA forces and also pledged their support to South African maneuvers. The war was now being fought directly between capitalist and communist leaning countries, as well as being supplied by the two superpowers of the world.

United States intervention in Angola was heavily shaped by several factors. First, much like in Vietnam, American leaders, such as Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, believed that a Communist takeover in Angola would lead to a “domino effect” in the rest of southern Africa. This belief was augmented by political and economic turmoil in the surrounding nations of Rhodesia (Zimbabwe), Zaire, and South West Africa. If Angola fell, it was feared that the Soviets, Cuba, and to a lesser extent China would feel bold enough to inspire revolution that was Pan-African and communist in nature, rather than nation-based and capitalist-oriented, throughout the African continent.

Second, offshore of the northern half of the country lay enormous oil fields. Neither the United States nor the Soviet Union wanted such reserves to fall into the other’s hands. Angolan oil could potentially benefit both nations economically and could also help cut costs of military operations in the continent should they arise in the future.

Third, the CIA feared that the Soviet Union was attempting to establish a military base in Angola. Such a concern was based on historical evidence. The Soviets had backed a 1977 coup led by former Interior Minister of Angola Nito Alves. Alves envisioned a globally integrated Angolan communist state, one heavily connected with the Soviet Union. He tried several times, unsuccessfully, to petition Neto, chairman of the MPLA, to build military installations for the Soviets in Angola, relatively close to the Western Hemisphere. Although Alves was eventually executed by Neto following the Nitista (a name given to the followers of Alves) coup, American officials knew that the Angolan War served as a real threat to its interests throughout all of Africa.

By 1976, the FLNA had collapsed as the United States switched to supporting the UNITA forces. Tensions between the MPLA and UNITA, and thus the Soviet Union and United States, respectively, increased throughout the mid-1980s. Between 1987 and 1988, the Angolan Civil War culminated in the Battle of Cuito Cuanavale. The MPLA was supported directly by Cuban soldiers and indirectly by Soviet advisors and weaponry, while the UNITA was backed directly by the South African Defense Force and indirectly by American money and weapons. Both sides claimed victory following the seven-month skirmish. Ultimately, due to economic limitations and growing casualties, the MPLA and UNITA leadership began peace talks.

The Angolan Civil War was crucial because it most clearly represented a clash of ideology between capitalism and communism on the African continent. For American interests, it was most important because Soviet military installations were not established on the Western coast of Africa. The civil war also destabilized southern Africa further, causing large refugee crises, increased ethnic tensions, and grudges based on former political allegiances. These factors combined to create conflicts in neighboring nations, creating several more civil wars and culminating in the 1998 Second Congo War, also known as the African World War.

South African Border War / Namibian War of Independence (1966-1990)

The South African Border War, also known as the Namibian War of Independence, was a prolonged battle between several governments and guerrilla movements. The war was essentially a battle for independence for South West Africa (now known as Namibia) from British influenced South Africa. Most of the fighting took place near the Angola-Namibia border. Due to this, the Border War inextricably became linked to the Angolan Civil War; oftentimes the two blended into one conflated battle based on Cold War ideological lines.

The main belligerents in the war were the South African government in the form of the South African Defense Forces (SADF), supported by the UNITA, the FLNA, and American arms, against the South West African People’s Organization (SWAPO), aided by the MPLA, Cuban military, and Soviet advisors.

The main belligerents in the war were the South African government in the form of the South African Defense Forces (SADF), supported by the UNITA, the FLNA, and American arms, against the South West African People’s Organization (SWAPO), aided by the MPLA, Cuban military, and Soviet advisors.

South West Africa had originally been a colony of the German Empire. As part of the Scramble for Africa, Germany occupied the area in 1884. Under German authority, the people of South West Africa faced a brutal regime that carried out several large massacres (often considered genocide) of the Herero and Namaqua people, beginning in 1904.

After World War I, Germany was forced to surrender its colonial possessions, and South West Africa became an administrative mandate under the trusteeship of South Africa. From the early 1920s until the mid-1960s, South Africa attempted several times to fully annex the territory of South West Africa but failed every time. However, the South African influence on South West Africa, especially under the apartheid government, continued to grow and alienate the people of South West Africa.

Guerilla warfare broke out in 1966 when small cadres of SWAPO backed insurgents, named the People’s Liberation Army of Namibia (PLAN), established base camps in the bush of northern Namibia. Several of their raids were repelled for the next couple years, but the fighting caused the UN General Assembly to revoke South Africa’s mandate over the area. More SADF and South African police streamed into South West Africa to pacify the region, making anti-South African sentiment grow. By 1970, SWAPO-backed militias had emerged throughout a majority of the country and began a rigorous guerilla campaign, centered around mine warfare.

By the mid-1970s, the limited bush skirmishes had turned into full-scale military operations aided by Western and Eastern Bloc allies. Angola became independent following the Carnation Revolution in 1974, and the country plunged into civil war. The delineation between Angola and South West Africa became almost nonexistent, and numerous SWAPO military camps were established within Angolan boundaries. The MPLA gained the upper hand in Angola, offering a strategic ally to the similarly communist-leaning SWAPO.

South African Minister of Defense P.W. Botha believed that South West Africa served as an effective buffer state between communism and South Africa. If South West Africa fell, however, South Africa would be the next logical area for communism to infiltrate — indeed, many black South Africans sympathized with communism, which promised prosperity for all compared to the rigid and racist infrastructure of apartheid which guaranteed black oppression.

The United States, too, viewed South Africa as the last bastion of capitalist friendly government in southern Africa. The United States was only able to offer limited help to South Africa, as full-fledged sponsorship for the racist regime would have been unpopular among democratic societies around the world.

Using covert military operations and a steady supply of resources, the United States attempted to bolster the SADF enough to maintain authority over South West Africa. The most effective way that the SADF maintained control over South West Africa was to push SWAPO forces into Angola and then continue the attack there. Several high profile missions, including Operation Savannah, Operation Protea, and Operation Askari, did just that. In most cases, the SADF was able to overwhelm the combined forces of SWAPO, MPLA, and Cuban militants supported by Soviet advisors because of the superior weaponry provided to the SADF by the United States.

However, the war dragged on well into the 1980s, and with every escalation by the SADF, the Cubans and Soviets doubled down on protecting SWAPO and MPLA territory. Although the South African forces inflicted far more losses than they received, domestic support for the conflict waned as no end was in sight. American support, too, dwindled, and talks between Soviet and American advisors toward a ceasefire began. The talks lasted into the late 1980s and a formal ceasefire was declared by the 1988 Tripartite Agreement. It stipulated that Cuban forces would withdraw from the African continent, SADF forces would leave South West Africa, and open elections would be held in South West Africa.

Namibia was granted and affirmed its independence in 1990. Within the context of the Cold War, the legacy of the South African Border War exemplified the tension between the United States and the Soviet Union. However, the actions by both nations showed how public opinion can influence public policy over time. When the war began, tensions between the two nations were high, but ebbed and flowed throughout the conflict’s twenty-four year duration. By the early 1990s, both the US and Soviet Union saw diminishing support at home – especially in the Soviet Union, where the economy was falling apart at the seams – for costly proxy struggles overseas.

Legacy

These proxy wars on the African continent represent just a small sample of the global scale of the Cold War. The ideological war between communism and capitalism claimed millions of lives and cost untold amounts of money. Unfortunately for most of the African nations swept up in these conflicts, their domestic issues were of secondary concern to the US and USSR. Because of these conflicts, numerous nations in central, eastern and southern Africa were destabilized economically, politically, and socially. Pervasive issues stemming from these conflicts remain to this day and show the painful legacy of the Cold War.

[1] Kris Hollington, Wolves, Jackals and Foxes: The Assassins Who Changed History (New York: Thomas Dunne Books, 2007), 50–65.

[2] Anon, “Somalia Says Two Towns Hit by Ethiopian Planes” Washington Post, December 29, 1977b.

[3] Cyrus Vance, Hard Choices: Critical Years in America’s Foreign Policy (New York: Simon &

Schuster, 1983), 83.

[4] Jerel Rosati, The Rise and Fall of America’s First Cold-War Foreign Policy. In Jimmy Carter: Foreign

Policy and Post-Presidential Years, ed. Herbert Rosenbaum and Alexej Ugrinsky (Westport, CT:

Greenwood, 1994).