Published: July 30, 2018

Updated: December 5, 2018

Uranite photo Courtesy of Rob Lavinsky

Uranium was discovered in 1789 by German scientist Martin Heinrich Klaproth in the mineral pitchblende. It was isolated shortly after, but its radioactive properties were not discovered until 1896 by Henri Becquerel. The discovery of uranium fission in 1938 led several countries to begin research into the possibility of developing an atomic bomb.

Scientists learned that Uranium-238 could be converted into a separate element, plutonium-239. For the fuel for atomic weapons, scientists needed fissile isotopes of uranium and plutonium. Uranium-235, which is fissile, would need to be separated from the much more common isotope uranium-238. Uranium could also be transformed into plutonium in a nuclear reactor. The demand for uranium mining and men to work those mines skyrocketed in the early days of the Manhattan Project, and would become one of its enduring legacies.

Uranium Mining

Uranium mining began on a large scale in the Czech Republic in the late 19th century as a way to procure ores for use in Marie Curie’s studies to isolate radium. Radium isolation continued to be uranium’s main purpose until the outbreak of World War II and the discovery that uranium could be converted into plutonium when using a nuclear reactor. Immediately, leaders of the Manhattan Project knew they would need to purchase and mine large amounts of uranium in a short amount of time. Created in 1944 and chaired by Brigadier General Leslie Groves, the Combined Development Trust (CDT) was tasked with this project.

Outside of central and eastern Europe in countries like the Czech Republic, Germany, and Ukraine, most uranium was located in central Africa, Kazakhstan, and Canada, with smaller quantities found in many western American states. Using funds provided by the CDT, in 1944 Groves would purchase more than 3.4 million pounds of uranium from the Belgian Congo alone, with lesser amounts purchased from Canadian and American companies.

Such large scale procurement and mining would come at a cost, however. This cost would not just be monetary, although the CDT spent close to $40 million in its first three years. Early uranium mining techniques and poor health and safety standards, coupled with rudimentary knowledge about radiation exposure, made working in the mines unsafe. This meant there would also be a tremendous human cost, both in Africa and the United States.

Uranium Mining in the Belgian Congo

Shinkolobwe Mine

Owned by The Union Minière du Haut-Katanga (Mining Union of Upper-Katanga) during the 1940s, Shinkolobwe uranium mine was located in the Belgian Congo.Uranium mining in the Belgian Congo primarily took place at the Shinkolobwe Mine owned by the Union Minière du Haut Katanga (Mining Union of Upper Katanga). It is located in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (previously known as the Belgian Congo and later Zaire), approximately 100 miles northwest of Lubumbashi. The uranium in Congo was especially pure; at times, the pitchblende where the uranium was embedded created sixty times more usable uranium than the average mine.

Groves struck a deal with the Belgian government — which was exiled in London at the time — granting them rights to the mine for uranium extraction. Edgar Sengier, director of the Union Minière du Haut Katanga, helped with the project. With an initial stockpile of 1,000 tons of uranium in New York, Sengier shipped an additional 3,000 tons from the African colony to America. Production at the mine would continue throughout the war, with several hundred tons being shipped monthly to the various Manhattan Project sites. Most of the uranium used during World War II was from the Congolese mines, and the “Little Boy” bomb the U.S. dropped on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945 used Congolese uranium.

However, the transportation of uranium across the Atlantic Ocean was an arduous task. The journey needed to be quick and secretive. German U-boats harassed Allied shipping constantly, making the route dangerous as well. Indeed, two of the forty uranium shipments from Congo to the United States were torpedoed and lost. Costs also skyrocketed into the hundreds of millions as the Shinkolobwe site and the roads connecting it to port cities needed to be drastically modernized. These obstacles played a large role in the diminishing importance of Congolese uranium after the war ended. Toward the latter half of the 1950s, the United States was more invested in keeping the uranium out of Soviet hands than actually mining the element itself.

Shrouded in secrecy, the mine’s human impact is almost entirely unknown. Few, if any, records were kept of initial working conditions there, though it is likely that they were subpar. Daily laborers worked for minimal wages around the clock to meet demand for the United States. By 1960, the United States no longer needed uranium from the Congo. The mine was officially closed in 2004, though later that year several people died when sealing one of the shafts. Artisanal mining — small-scale, subsistence mining — continues to this day. Most of the minerals, such as cobalt and copper, are mined illegally and sold on the black market. However, uranium deposits still exist at the site, a fact which has recently worried outside observers. Radioactivity from the uranium’s decay continues to be released into the environment. In 2006, it was also discovered that some uranium was being smuggled out of the country. Following an investigation by the UN Security Council, it was determined that the uranium was likely headed to Iran.

Navajo Uranium Miners in Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah

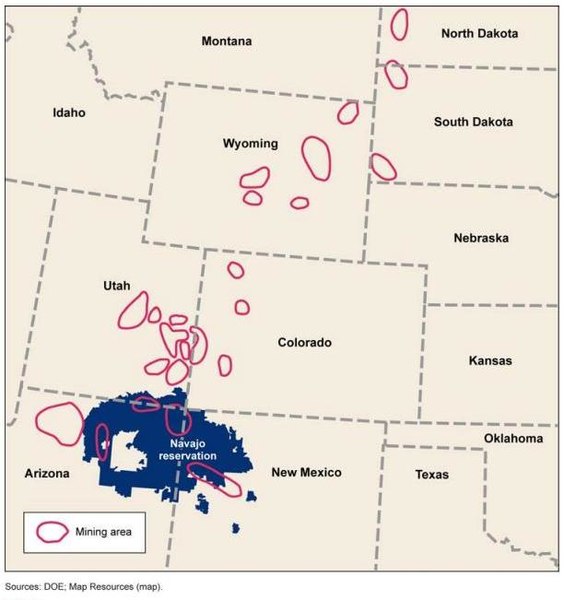

The importance of imported uranium from Africa dwindled primarily due to increasing costs. Improved refinery methods also contributed to the shift toward domestic mining. Doing so enabled scientists at Hanford, Los Alamos, Berkeley and Oak Ridge to enrich low-grade uranium into a more purified form so it could be used in nuclear weapons. Given these developments, it became obvious that the Atomic Energy Commission needed to find a uranium source closer to home. Several areas in the arid valleys of the southwestern United States held considerable amounts of the radioactive element. The reserves were located in sparsely populated areas, but had a marked impact on the communities nearby economically, socially, and politically. In addition, the adverse effects of uranium mining in this region disproportionately affected minority communities, specifically local Native Americans.

The Navajo Tribe is one of the largest Native American tribes in the United States. The Navajo Nation reservation is the largest, by land, in the United States, spanning approximately 27,000 square miles. The Navajos reside primarily in Arizona, New Mexico, Utah and California. They consider themselves extremely close with nature and historically have excelled at weaving and silver working. As with many Native American communities, traditional life for the Navajo Nation has grown increasingly difficult. One of the largest issues facing the Navajos concerns the lasting environmental legacy that the Manhattan Project and the Atomic Energy Commission have had on their lands.

Uranium Mining in the United States

Carnotite, a radioactive mineral, existed in abundance across New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado, and Utah. For years carnotite was mined almost exclusively for its vanadium and radium. Vanadium was used for strengthening alloys, especially steel, while radium was a commodity after its discovery in 1898. It was used extensively in scientific projects conducted by Marie Curie and later was used as a luminous paint for watches, aircraft switches, and clocks. However, carnotite also contained uranium, and this became the primary reason it was mined as the Manhattan Project concluded and the Cold War began.

Uranium milling is the process by which uranium ore is separated from other minerals, yielding dry-product referred to as “yellowcake.” No matter which process is used for milling, large amounts of water are used to dissolve other minerals and keep the uranium particles from floating away. This water becomes highly irradiated, and must be kept in large storage bins so that its radioactive elements can decay.

Following the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the demand for more uranium to produce nuclear weapons increased dramatically. Mines sprang up rapidly on Navajo land, as several large carnotite deposits were found, or had been found previously, on the various plateaus on the reservation. Though the Navajos had succeeded in preventing widespread mining incursions in previous years, they were unable to do so as the Cold War intensified. Navajo leaders did not appreciate these intrusions into their land, but the sudden influx of capital in the area also enabled many unemployed Navajo men to get jobs in the mines and earn a substantially higher income than they otherwise would have. Miners worked without any protective equipment and often exposed their families to the radioactive dust left on their work clothes. Additionally, many Navajo and other tribal groups built their homes with material from mine sites or drank from contaminated pools of water, as they were never informed about the dangers associated with uranium mining.

Work continued constantly, as the mines attempted to meet the ever-growing demand for the radioactive element during the Cold War arms race with the Soviet Union. More than 1,000 mines were established across the Navajo Nation reservation, with almost 4 million tons of uranium being mined there from 1944-1989.

Church Rock Uranium Mill Spill

Small accidents at the uranium mines were not uncommon. However, one mishap in particular has increasingly gained attention, though it was largely ignored at the time. The incident occurred at the Church Rock uranium mill, 20 miles north of Gallup, New Mexico, directly adjacent to Navajo land.

On July 16, 1979, the Church Rock uranium mill experienced the largest release of radioactive material on United States soil. The south cell disposal pond experienced a massive, twenty foot breach in its wall — likely caused by numerous six-inch cracks in the cement.[1] The wall, which acted as a dam to keep the radioactive waste in the pond, was located directly next to Pipeline Arroyo, a tributary for the larger Puerco River. In all, 1,100 tons of solid radioactive waste and 93 million gallons of liquid waste ended up in the river.

Government and private cleanup efforts following this spill were slow. Some Native American communities did not even realize there had been a disaster until several days later. Numerous wells were contaminated, with almost all being abandoned in subsequent months rather than cleaned. In some places, the radioactivity levels in the water were up to 7000 times that of legal drinking water. The spill received little attention largely because it happened in such a rural area —despite the fact that the amount of waste released in this accident far exceeded the waste released in the Three Mile Island accident, probably the most high profile nuclear accident in American history. Immediate health consequences included radiation burns for some children who swam downstream following the spill and the death of wildlife due to ingesting large amounts of the water. Long-term consequences remain inconclusive.

Health Legacy and Compensation

Recent studies suggest that Navajos who worked in, or lived very close to, the uranium mines in Arizona and New Mexico have suffered numerous health complications, including lung cancer and various pneumoconioses. Stomach cancer, too, is fifteen times higher than average among the Navajo communities, while in some areas it reaches close to 200 times. Due to lifestyle choices and genetics, these Native American communities were less likely to get cancer and other illnesses beforehand, making the changes in their incidence rates more drastic. The federal government initially scrutinized these findings because of the small sample sizes used, which may have delayed compensational funding for some time.

Reparations were finally approved in 2000 following yet another study that indicated that members of the Navajo community were suffering from radiation related diseases. This funding was attached to the already existing Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA), which initially did not cover uranium mill workers and others exposed due to uranium mining. The amendment also made the claimant process more streamlined, enabling Navajo workers better access to the benefits they were due.

While these reparations are an ongoing remedy to years of hardship that the Navajo as a community have experienced, challenges still persist. Language barriers and inaccessibility to medical clinics or civil courts where individuals might start their claimant processes remain difficult obstacles to surmount.

Abandoned Mines and Continuing Impact

The legacy of the uranium mines on Navajo lands persists to this day. Most of the mines are abandoned in various spots throughout the landscape, with more than 500 mines being designated under a single Superfund cleanup project by the federal government. Most of these mines are unsealed and present possible health risks until properly cleaned, especially because many of them are completely unmarked. Cleanup continues and will so for years, as funding is limited and costs millions of dollars per year. The decontamination scope has also expanded over the last several years, with water sources being added to the list of polluted areas. The program has received some backlash from local communities, however, due to its low rank on the National Priorities List. Using this system, sites that are considered the most harmful to humans are cleaned first, while other projects are shelved for later cleanup when more funds become available. This has caused many of the most contaminated mines to remain unclean, as they lie in relatively low-density population areas.

The abandoned mines present a unique health risk, as they constantly emit radioactive elements into the air, but often remain unseen by the public. Until these mines are cleaned up, it is likely that individuals living near them may continue to experience the negative consequences that come with breathing in irradiated air or drinking irradiated water. No legislation has been passed regarding individuals exposed to radiation this way, as RECA benefits only apply to those who worked in the mines themselves. Going forward, the issue of reparations due to exposure from unsealed mines will remain a large issue for the Navajo Nation. Several lawsuits regarding the topic remain pending, but no cases have been resolved yet.

Uranium Mining in Other American States

Uranium mining was also carried out in several other American states. Idaho, Utah, South Dakota, North Dakota, Texas, Arizona, Washington, Oregon, and Wyoming are all states where uranium miners are covered under the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act. Historically, these states have been associated with a variety of mining booms, from silver and gold to vanadium and radium. The uranium deposits in these states are located along fault-line ridges that dot the rural landscape. Almost all the mines existed as vanadium, radium, and then as uranium mines, with each element extracted and refined in response to the demand for it at the time.

The negative health consequences experienced in these communities are slightly less pronounced than those observed in the Navajo Nation. Health consequences still exist, however, as many community members in these states were kept in the dark about the harmful effects of radiation. Miners and local residents as young as four have died of cancers and other lung related illnesses in subsequent years.

The environmental and health impacts of radiation are still prevalent in these communities, but the more pronounced effect in many of these mining towns was the loss of community. Mining, in general, is an industry that experiences booms and busts periodically. This cyclical structure is amplified when it came to a volatile mineral being mined, such as uranium. Demand for the element plummeted in the early 1980s because of minor thawing in American-Soviet relations, which prompted the federal government to buy less uranium. This forced entire towns to close their doors.

One such town, Uravan, Colorado, ballooned in population from several dozen people to over 800 in a span of less than twenty years. By the mid-1980s, every single family had moved away from the town and a Superfund was set up to clean the area. This cleanup effort involved completely destroying and burying all previous infrastructure of the town. The total erasure of buildings, homes, and parks created a certain disconnect for former residents from these towns, a lost identity they struggle to recreate and maintain.

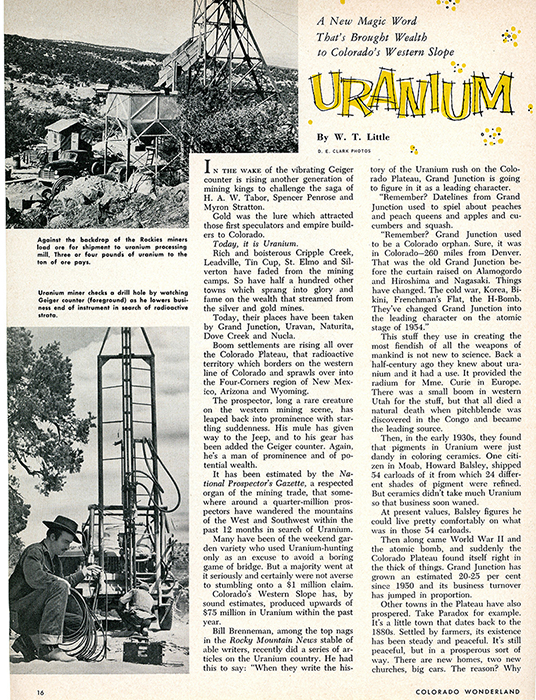

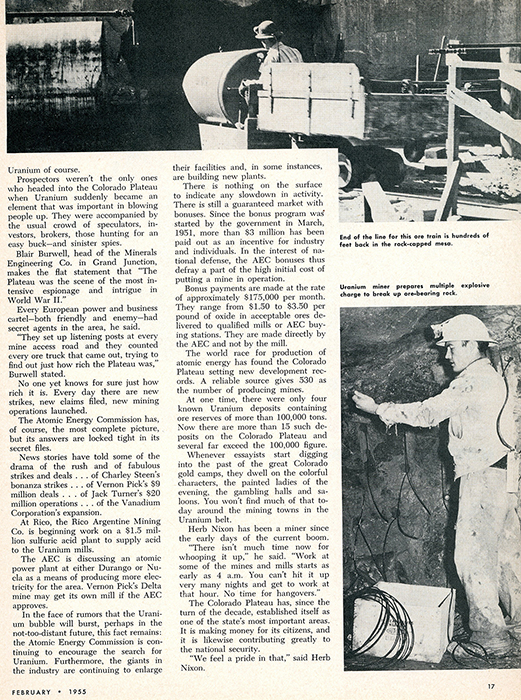

Magazine article about Uranium mining in Colorado

Legacy

The legacy of uranium mining is ongoing. While the miners themselves are covered under RECA, their family members remain uncompensated. Work continues on cleaning up and sealing the mines, a process that is slow and expensive. Only a few uranium mines remain operable in the United States, yet the legacy of uranium mines used in years past continues to impact individuals and communities, and will do so for the foreseeable future..

[1] Judy Pasternak, Yellow Dirt: An American Story of a Poisoned Land and a People Betrayed (New York: Free Press, 2010), 149.