Manhattan Project scientists, workers, and families needed diversion to deal with the high pressure and intense secrecy of working at Los Alamos. As wives and children also began living on the Hill, Los Alamos’s residents began to organize many different means of recreation and leisure.

Family Life at Los Alamos

“It was the pre-baby boom baby boom,” recalled Ellen Bradbury Reid, who was a child at Los Alamos. “I think it cost a dollar to have a baby so everybody did.”

Each of these babies had PO Box 1663 on their birth certificate, the mailing address for the whole town of Los Alamos. This high birthrate transformed Los Alamos, leading to the construction of a school and a bigger hospital wing. John Mench, a member of the Special Engineer Detachment, recalled that his wife went into labor at the laundromat:

“My wife went to the laundromat one day, stood in line, and while she was standing in line started her labor pains. But being a stubborn Johnny Bull who was born in England, she gritted her teeth, kept her place in line, got her laundry in the washing machine eventually, got her washing done, folded it up, put it in her basket, and called her girlfriend to take her to the hospital because she was going to have our second daughter.”

Part of the reason for the high birth rate was the appeal of Los Alamos as a safe environment to raise children.

Part of the reason for the high birth rate was the appeal of Los Alamos as a safe environment to raise children.

“Los Alamos had no crime. There was no kidnapping. It was an ideal situation to have children—to be able to have this kind of freedom, to grow up in this environment,” said Dolores Heaton, who was a child at Los Alamos.

“That was free, enjoyable, it was fun,” Heaton continued. “We would stay out until two o’clock in the morning if we wanted to, going to other people’s homes. We had a youth center there that they made for us. Questions were never asked.”

“You could go any place you wanted to,” Esther Vigil remembered. “You could play in the canyons, where security would watch out—they knew the kids would sneak under the fences into the canyons. They would just keep an eye out, and so made sure they were all right when they snuck back.”

Many children attended a school set up by scientists’ and workers’ wives. However, the end of the school day could be chaotic. “There were a lot of children in Los Alamos, and so they decided to have a school bus,” remembered Robert Howes Jr. “The first time it drove down the street, it opened the door and kids got out like hamsters all over the place. Nobody was expecting them not to be civilized. Cars had to screech to stop and everything, and after that the parents got together and tried to make rules for such things.”

For the most part, however, keeping track of children was fairly easy. Once a child turned 6, he or she received the standard ID pass to go in and out of Los Alamos.

“If parents didn’t want their children going off of the Hill, all they had to do is take their ID card away from them and they weren’t going anywhere,” Heaton remembered. “Because at that time to get and out of Los Alamos you had to have your badge and your ID card. There were no ifs, ands, or buts about that.”

Parties at Los Alamos

Having families on the Hill helped combat some of the isolation felt by the scientists and workers of the Manhattan Project, but it did not entirely solve their stress.

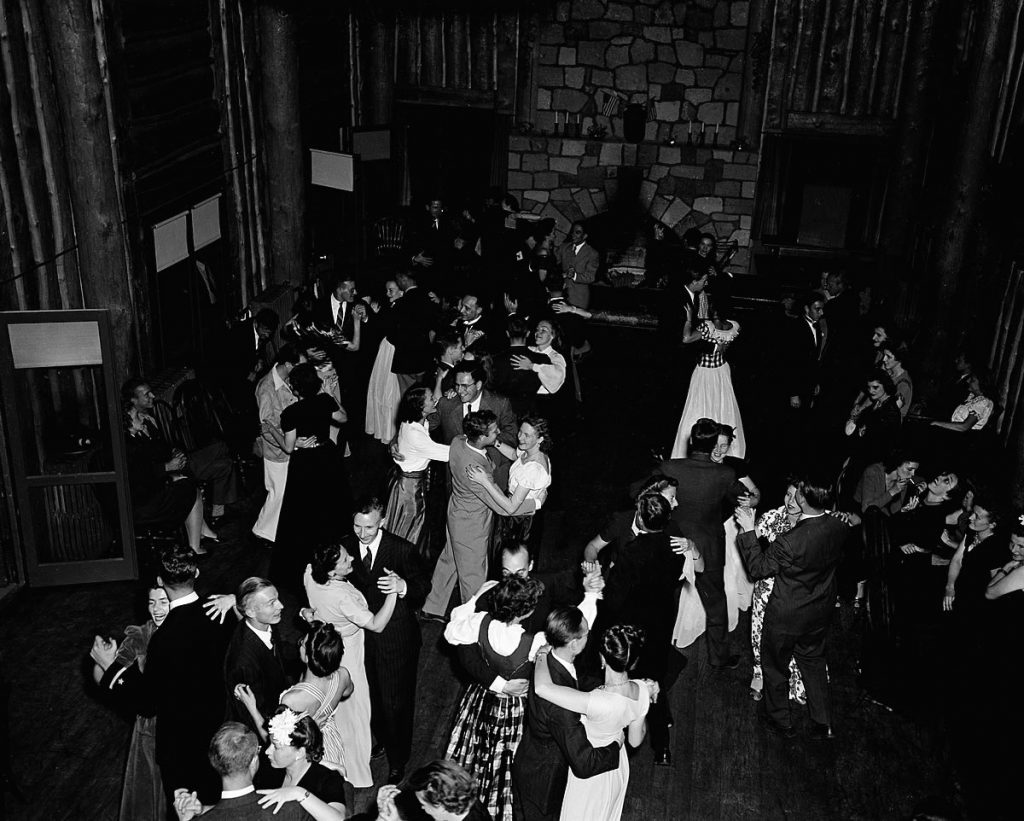

“We were tired. We were deathly tired,” remembered Elsie McMillan, the wife of scientist and future Nobel Prize winner Edwin McMillan. “We had parties, yes, once in a while, and I’ve never had so many drinks as there on the few parties. Because you had to let off steam, you had to let off this feeling of your soul, your ‘God, am I doing right?’ You had to.”

At these parties, the scientists and their wives dined, drank, danced, and discussed everything but their work. “Instead of being like most scientific evenings that you get used to – the men go off in a corner, and get to talking about what they are interested in – they could not do this,” said Jean Bacher, who was married to scientist Robert Bacher. “You would have some fascinating conversation. You would have a chance to talk about something besides science. You see, they couldn’t mention anything that they were working on.”

“Everyone was dancing, and we all had a marvelous time,” recalled Louis Hempelmann, director of the Health Group at Los Alamos. “Had we drunk the same amount at a lower level, it would not have affected us at all, but I think that is what gave us such a good time. Oppie danced in the same way, in this old worldly manner, holding his arms way out; classic.”

“Everyone was dancing, and we all had a marvelous time,” recalled Louis Hempelmann, director of the Health Group at Los Alamos. “Had we drunk the same amount at a lower level, it would not have affected us at all, but I think that is what gave us such a good time. Oppie danced in the same way, in this old worldly manner, holding his arms way out; classic.”

Other workers held their own parties in the dormitories to also let off steam after a long week. “Everybody in my dorm would get together, chip in, and give a dorm party. Because it was dusty, muddy, rainy, snowing, you wore boots and things to work. We always specified “formals” for the ladies so we could dress up for something,” said Rebecca Diven, who worked with plutonium at Los Alamos. “We’d have a crew set up and clean up and then we would have punch in which somehow alcohol would magically appear, and we could make punch and different things.”

Albert Bartlett, who worked with mass spectrometers, described where this alcohol “magically appeared” from:

“The basic ingredient of the punch in the dorm parties was ethyl alcohol from the laboratory stock. Now, I suppose it’s still true that if you’re running a university chemistry laboratory, you have to keep very careful inventory records of your ethyl alcohol stock. But here, you could just go and get whatever you needed. For punch, apparently, somebody knew how to pull the strings to get it, and there weren’t any federal inspectors around checking on it. A lot of times, the punch was pretty strong.”

But the requisitioning of alcohol took a tragic turn, Bartlett related. “The word got around, and then sort of the inevitable happened. Some of the custodial people apparently went in to the chemical supplies to get something for some punch they were going to have, and they got ethylene glycol [antifreeze] instead of ethanol.”

The three men, janitors Manuel Salazar, Alberto Roybal, and Pedro Baca, passed away from ethylene glycol poisoning on January 29, 1946.

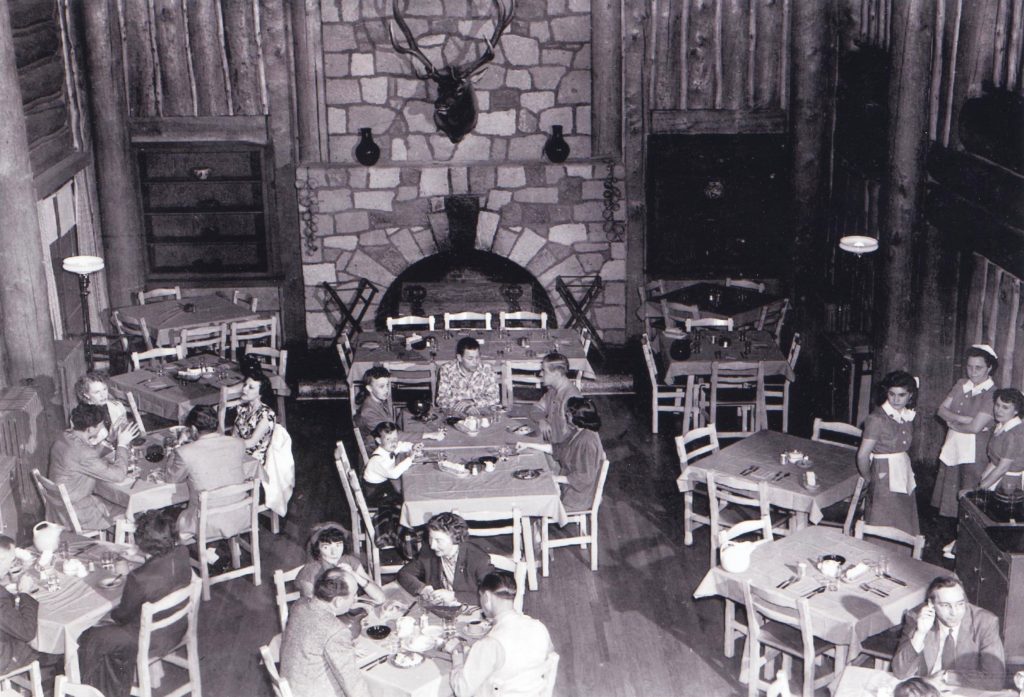

Food at Los Alamos

Although alcohol could be difficult to procure, workers at Los Alamos did not have same difficulties obtaining food. It was readily available at the Post Exchange and the mess halls.

Although alcohol could be difficult to procure, workers at Los Alamos did not have same difficulties obtaining food. It was readily available at the Post Exchange and the mess halls.

“The mess hall sergeant was very good if you were going to go on a picnic someplace,” said Diven. “You could go and say, “I would like some meat for a barbeque on a picnic,” and he would give you from the mess hall what you needed for the picnic and he would give you other supplies if you needed it. Or you could have your coupon book to have some canned things if you were going camping. That wasn’t very practical because canned goods were heavy, but you would use them for whatever you needed at that point, or for dorm parties.”

Because scientists came from diverse backgrounds, Los Alamos featured wide variety of types of cooking. J. Robert Oppenheimer in particular was famous for his interest in cooking. Nevertheless, the high altitude of Los Alamos made cooking difficult. Peggy Bowditch, then a young girl, recalled a cooking experiment that ended up as an inedible dish.

“I did try to cook at Los Alamos. Our mother was not a cook, and I would get a cookbook and my sister would be the lookout, you know. When Mother came home, she did not want to catch us messing up the kitchen,” Bowditch said. “Following the Joy of Cooking, which was not written for that altitude, I made the worst mess. I mean, even my sister and I could not eat it. And when she’d would call out that Mother was coming, I would quickly ditch the pan of failed brownies on a lilac bush outside the back door, and then quickly clean it up. Years later, when I went back to the house, I checked the health of the lilac. Apparently, it liked my cooking even though it was inedible.”

Others, like John Mench, were more successful in cooking. “When the MPs who were on patrol brought us game, we had a huge pot which sat on top of these potbellied stoves,” Mench said. “We constantly kept a critter stew going in the barracks, which could be attacked any time that we wanted for a meal—always hot. And we’d swiped—well, we say “swiped,” but I think the mess sergeant turned his back, let it happen—we borrowed onions and carrots and potatoes and things and added it to venison and rabbit and turkey and sometimes quail, all put together in the same pot. And all of us imbibed in that stew. It was delicious.”

If Manhattan Project veterans were lucky, they would be invited to eat at Miss Edith Warner’s house on Otowi Bridge. “Joe [Kennedy] and I were invited by Oppie to have dinner there a couple of times,” said Adrienne Lowry, who was a mail courier at Los Alamos. “And she provided a fabulous meal, gosh! She was famous for her chocolate cake, and I think a lot of us left Los Alamos with her recipe on how to make Edith Warner’s chocolate cake.”

Places to Go and Things to Do

As Los Alamos continued to grow, so did its forms of recreation and leisure. The military established a recreation director and initially had two GIs to lead recreation, Corporal Tom Fike and Caesar Bango.

“There would always be groups doing one thing or another,” Bacher remembered. “There was a poker group and square dancing group and music groups of all kinds. It was the most organized place you had ever seen.”

Others also described a small lake, a bowling alley where you had to set your own pins, and man-made ice skating rink. “The military also built us an ice skating rink,” said Heaton. “There were great big shovels that we would use to push to clean off the snow so we could go ice skating. It was a little far from the main neighborhoods where we lived. In order to get there, an Army pickup truck would pick us up. And we would all climb in the back of this pickup truck and they would take us to the ice rink.”

Two theaters, Theater One and Theater Two, were a popular destination for the older crowd at Los Alamos. “We got to see a lot of movies, and it seemed like John Wayne was in most of them, either as a cowboy or the head of some commando outfit in the war,” Mench recalled. Of the two theaters, Theater Two was more popular and was the headquarters for the operations of the Army recreation department.

“This was an all-purpose building,” said Bob Porton, who worked for the Army recreation department. “It was built originally as a huge warehouse, but in that building, we ran dances on Saturday nights. Then we had to clean up the place and get some custodians who lived at a barracks next to it in about four o’clock in the morning, and get it all ready for church services. The chaplain did not want his podium on the stage, he wanted it the other way, so they wouldn’t face the stage and there were big huge benches in there that we had to move around. So the next morning had church services. When church was over, we had to turn everything back around because at two o’clock we had Army motion picture services.”

“It was used for everything under the sun. We had plays in there, we played basketball in there,” said Mench. “The women in the area—married women who did needlework or something—held parties in there for making quilts and things like that. Everything that ever happened in Los Alamos, whether it was a convention or whatever, was held in Theatre Two.”

Popular events at Theater Two included big dances that featured Los Alamos band “The Keynotes.” This band, created by Harold Fishbine, who had been an amateur musician before the war, played Big Band classics. The band continued to play after the war, doing gigs in Santa Fe. Two other bands at Los Alamos were called Los Cuatros and Sad Sack Six.

Popular events at Theater Two included big dances that featured Los Alamos band “The Keynotes.” This band, created by Harold Fishbine, who had been an amateur musician before the war, played Big Band classics. The band continued to play after the war, doing gigs in Santa Fe. Two other bands at Los Alamos were called Los Cuatros and Sad Sack Six.

“Dancing was also a favorite. Square dancing. The military base commander was particularly interested in square dancing, so he naturally was all for it and was generally the head man there at the square dance,” recalled Berlyn Brixner, a photographer and camera engineer. “They had plenty of people who were good at music playing, so they had plenty of music.”

In addition to the dances, Los Alamos also had its own orchestra and even put on plays. “My wife had been interested in plays before coming to Los Alamos, so a group of people soon got together and were presenting plays and my wife was among the actresses,” said Brixner. “They used to bring me in for set construction and that sort of thing. I was kind of a carpenter and painter and what have you to try to get sets made, and we had everything we needed to do those. They made very nice plays. They were enjoyed by everybody.”

Another form of recreation was through the radio station, KRSN. It had a small frequency and was meant to be only for the community of Los Alamos. However, this didn’t work so well.

“In retrospect, it is pretty funny: in a place that was so obsessed with secrecy, certainly you could hear the radio station outside the fence,” said Reid, whose family lived outside the fence of Los Alamos because her father’s work required him to be closer to S-Site.

The radio station’s programming was varied, but mainly catered to the musical tastes of the Los Alamos community. “People were really very interested in music and they had amateur theatricals, particularly when the British got to Los Alamos. The Brits of course loved to do the crazy skits and they did Gilbert and Sullivan. There was an interest in music and theater and culture,” Reid remembered. “Maybe you would have in part called it a classical music station; people loaned them records and they played records. [Edward] Teller would sometimes play the piano for them and the announcer Bob Porton was there for a long, long time.”

Other music lovers like Benjamin Bederson, who was an SED, satisfied their musical cravings in a different way. “We had the amplifier, the large speaker and a record player set up in Richard Bellman’s office,” Bederson said. “Norman Greenspan and I decided to form a society where we could listen to classical music. We called it the Mushroom Society, because we could only meet at night when there was nobody there. We would play music very loud, Mahler and Beethoven, Wagner, and all of the classics very late at night, and really enjoying it.”

Leaving the Gates

On rare occasions, Manhattan Project scientists and workers were permitted to leave Los Alamos, whether it was to visit the Pueblos nearby or to go into Santa Fe. Those who visited the Pueblos, like Elsie McMillan, usually did so on the invite of their Pueblo housemaids.

“We had the great privilege of going down to the Pueblo and having lunch with the Penas many times,” Elsie McMillan remembered. “They all cooked their bread in the beehive ovens with their pottery, the black San Ildefonso.”

Those who visited Santa Fe were able to briefly escape the secrecy and tension of Los Alamos. Although they were sworn to secrecy, Manhattan Project veterans cherished the trip.

“We were allowed one day a month that did not count against sick leave or vacation to go shopping because you couldn’t buy a thread—a spool of thread—anything on the Hill. And if you made the mistake of saying, “I’m going to town,” you left with a long list of purchases for people on the “G-Mind” bus,” described Diven. “It went down on sort of a regular schedule, you could get there by the times the stores opened. And then I could get back in half a day and go hiking, whatever, and do the shopping we needed because there was nothing here in ’44. I loved it. I thought it was wonderful—mud, dust, wind, that’s all right.”

-1024x783.jpg) Leaving Los Alamos also could mean exploring the majestic New Mexico landscape. Many workers and scientists enjoyed activities such as skiing, hiking, and horseback riding. “More than once, somebody would bang on my door before breakfast and say, ‘Wake up! It’s snow. Let’s go skiing!’” said Diven. “I’d jump up and we’d ski, and miss breakfast incidentally, and then I’d get to work in time. I thought that was heaven. Imagine being able to go right out of your dorm room into a place where you could ski or hike in the mountains. That sort of thing was essential to me—hiking and skiing and being in the mountains.”

Leaving Los Alamos also could mean exploring the majestic New Mexico landscape. Many workers and scientists enjoyed activities such as skiing, hiking, and horseback riding. “More than once, somebody would bang on my door before breakfast and say, ‘Wake up! It’s snow. Let’s go skiing!’” said Diven. “I’d jump up and we’d ski, and miss breakfast incidentally, and then I’d get to work in time. I thought that was heaven. Imagine being able to go right out of your dorm room into a place where you could ski or hike in the mountains. That sort of thing was essential to me—hiking and skiing and being in the mountains.”

Heaton vividly described New Mexico’s spectacular scenery. “It was one of the most beautiful settings I think that I’ve ever seen in my life. We were covered by mountains on all sides—north, south, east, west were nothing but huge, huge mountains. They were absolutely incredible. I have to go back there periodically and get my mountain fix because it gets into your system, into your little brain. There’s nothing to take the place of those gorgeous, gorgeous, gorgeous mountains.”

The quotations in this article were drawn from the following interviews on the Voices of the Manhattan Project website:

Elsie McMillan, speech from Los Alamos National Laboratory Collection