AHF is involved in many preservation efforts at Hanford, WA. Our most notable accomplishments include our work on the B Reactor in Hanford, WA. AHF was involved in the successful effort to prevent the B Reactor from being cocooned. Today it is a popular tourist destination. More than 40,000 visitors have toured the B Reactor since 2009 from all 50 States and over 68 countries. If you can’t visit yourself, take a virtual tour with our “Ranger in Your Pocket: B B Reactor Tour” site.

To learn more about touring the reactor, visit the B Reactor Tours website. To view a map of the historic districts and sites in Hanford, please click here.

Preserving the B Reactor

As the first large-scale plutonium production reactor in the world, the B Reactor produced the fissile material for the Trinity test device, the Fat Man bomb detonated over Nagasaki, and a portion of the United States’ Cold War arsenal. Its fate has been unclear, however, since it was decommissioned in 1968. With the end of the Cold War, efforts to clean up Hanford accelerated and it appeared that the historic B Reactor would join other reactors in being “cocooned.”

The Control Panel at B Reactor

Friends of the B reactor worked tirelessly to prevent it from meeting a similar fate. Groups such as the B Reactor Museum Association, the Hanford Communities, the REACH Museum and the Atomic Heritage Foundation lobbied both local and national leaders to preserve the building with a goal of someday opening it to the public. In December of 2007, these forces won a major victory when a Department of Interior committee voted unanimously to recommend National Historic Landmark status for the reactor.

On March 12, 2008 the Department of Energy agreed to move forward with their part of such a plan and removed it from their list of Hanford properties to be dismantled. Assistant Secretary of Energy Jim Rispoli released a statement saying, “The B Reactor stands as a tribute to the ingenuity and dedication of the men and women who pioneered a nuclear technology in the hope that our nation’s security would be preserved for future generations. The steps we are taking will ensure we give this remarkable facility every chance to be permanently preserved for the public to see.”

The B Reactor has been open to the public for tours since 2009. Today schoolchildren 12 and up can visit the reactor, which have been described as “Amazing” and “incredible.”

In 2012, the Department of Energy received a $5 million allocation to preserve and restore buildings at Hanford. The funds will go towards a new roof for the B Reactor.

Trains and Cask Cars

Cask cars at Hanford

Trains were an important part of the smooth functioning of the Manhattan Project at Hanford. After irradiated fuel from the B Reactor had cooled off in the storage basin full of water for about 90 days, workers used twenty-foot long tongs to place the irradiated fuel into buckets.

To transport the fuel to the chemical separation plants, engineers designed special lead-lined cask cars. The fuel elements were loaded, under water, into a cask, which was sealed with a lid. A locomotive pulled the cask cars for their ten-mile journey to the three chemical separations plants, entering them through a railroad tunnel. Two 125-ton locomotives and two cask cars are on display at B Reactor. A bucket with fake slugs illustrates the once “hot” cargo.

Locomotive at Hanford

Thanks to generous grants from Watson Warriner and Clay and Dorothy Perkins, the Atomic Heritage Foundation plans to repaint the lead locomotive to its original orange and black Hanford Engineer Works colors. Missing builders plates will be replaced for both locomotives.

Department of Energy restrictions on donations have delayed the painting, but once the Manhattan Project National Historical Park is established by Congress, the paint job should be possible.

AHF hopes to raise funds for interpretive panels to explain the role of the locomotives and cask cars on display. The panels can also inform visitors about the significant role of railroads at Hanford. Twenty-three steam locomotives provided heat for 50,000 workers at the Hanford construction camp in the early days of the project. Eventually, forty thousand freight cars delivered materials on 158 miles of new track.

For more information about the trains and cask cars at Hanford, please click here to download a pamphlet.

Pre-War Hanford Sites

The first Euro-American settlers arrived in White Bluffs in 1861, establishing a town on the east bank of the Columbia River near what is now the 100-H area of the Hanford site.

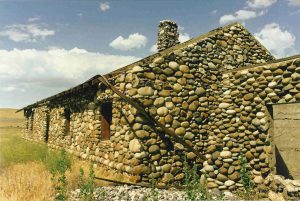

The Bruggemann Ranch House

Before World War II, the White Bluffs community had a population of about 1,000 with tree-lined streets and white clapboard homes and stores. Other buildings included an elementary and a high school, the White Bluffs Inn, railroad depot, White Bluffs Motor Company, bank and ice cream parlor.

Today, there are just a few indicators that White Bluffs even existed. Almost all of the buildings were demolished. Even the surrounding orchards were chopped down to stumps. The only remaining structure in the townsite is the White Bluffs bank. The bank was supposed to be impervious to robberies, but the wooden roof of the vault was exploited by bank robbers on at least one occasion. Now the weather is its biggest threat.

About 1,000 people in unincorporated areas on the Columbia River were also evicted by the Manhattan Project. Virtually all of these properties are now gone except for traces of irrigation ditches, foundations, curbstones and the stumps left from former orchards. One remarkable exception is the Bruggemann ranch building near White Bluffs. The building is a sturdy structure, constructed from riverstones from the nearby Columbia held together with concrete. It is all that remains of the 540-acre farm belonging to the Bruggemann family.

Today, the Bruggemann building remains an impressive example of the ingenuity of the area’s early agricultural settlers. It is near the Vernita Bridge and within two miles of the B Reactor. The plan is to restore the building and construct an additional one patterned after the original farmhouse. The properties could be a gateway to the Hanford site and an interpretive center for the history of those who lived along the Columbia River before the Manhattan Project.

The town of Hanford, after which Hanford Engineer Works was named, was settled in 1907 on land purchased by the Priest Rapids Irrigation and Power Company. Constructed in 1916, the Hanford High School had art deco-style architecture, unusual for a small farming town. Its gymnasium had highest-quality hardwood floor. In early 1943, it was used as offices by the Manhattan Project. Later, the building was reportedly used for bombing practice and SWAT team training, damaging the building until only the outer shell remains.

In 2012, the Department of Energy received a $5 million allocation to preserve and restore buildings at Hanford. The grant will help restore pre-World War II sites, including the Bruggeman Ranch building, the White Bluffs Bank, and stabilize the Hanford high school.

The T Plant

The T Plant was used to chemically separate plutonium from the irradiated fuel rods, a crucial role in the plutonium production process. A first-of-a-kind facility, the T Plant is still used by the Department of Energy today for handling radioactive waste.

On October 5 and 6, 2013, the T Plant was open for public tours for the first time. Some of the historic artifacts from the T Plant may be put on display at the Hanford REACH Interpretative Center, to open in July 2014.

Interpreting Hanford’s History

The Atomic Heritage Foundation has developed several exhibits for the B Reactor. Most recently, AHF developed two models in consultation with the B Reactor Museum Assocation. The models have been on display since April 2013.

The first model helps visitors understand the importance of the Columbia River and the dozens of auxiliary buildings that once surrounded the B Reactor. The 8’x8’ model will show what the site looked like in 1944 with 20 buildings surrounding the reactor. Lights on the model will trace the flow of water from the Columbia River, through several pump and treatment buildings, to the reactor and back into river.

The second is a display that enables visitors to understand how the “pile” of graphite blocks and process tubes worked. The exhibit displays some 1940s vintage graphite blocks as if they were in installed in the core of the reactor. Panels explain how exacting the engineering of the blocks was to ensure the smooth operation of the reactor.

A series of video vignettes complements these two exhibits so that visitors can learn more about the role of the Columbia River and the design of the graphite “pile.” In addition, tourists to the B Reactor can access AHF’s “Ranger in Your Pocket: B Reactor Tour” on their smartphones.