World War II along the Columbia River

Stretching from coast to coast, the Manhattan Project grew into an enormous national effort during World War II, employing more than 600,000 temporary and permanent workers. In January 1943, the remote Hanford site in eastern Washington State was selected for the Manhattan Project’s top-secret site for plutonium production. The site occupied approximately 580,000 acres with some fifty miles of the Columbia River flowing through the high desert steppe. Within months, 50,000 workers were constructing the first-of-a-kind reactors and other plutonium production facilities.

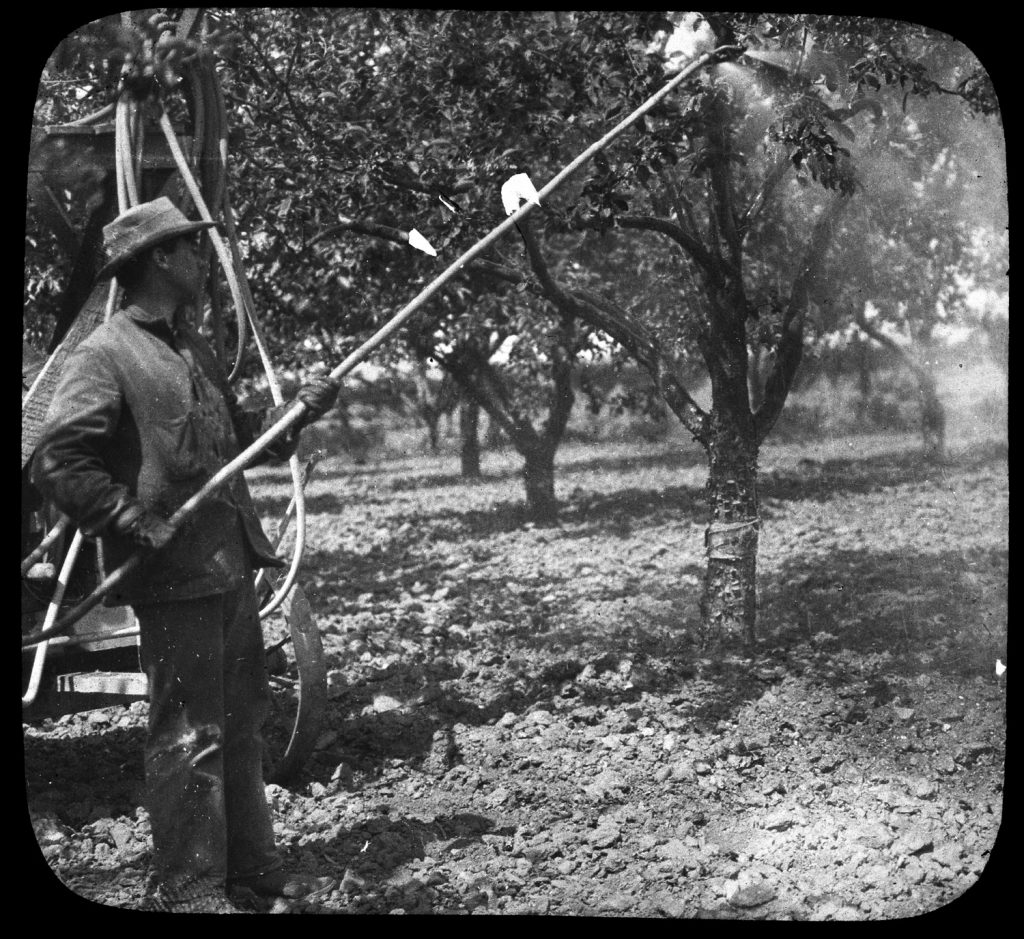

Before the government took over, about two thousand people lived in the communities of White Bluffs, Hanford, and Richland or managed farms and orchards nearby. For centuries, four different Native American tribes enjoyed the land along Columbia River for camping, hunting, and fishing. Abruptly, the government notified them that they had to leave the land, disrupting their personal lives, communities, and traditional ways.

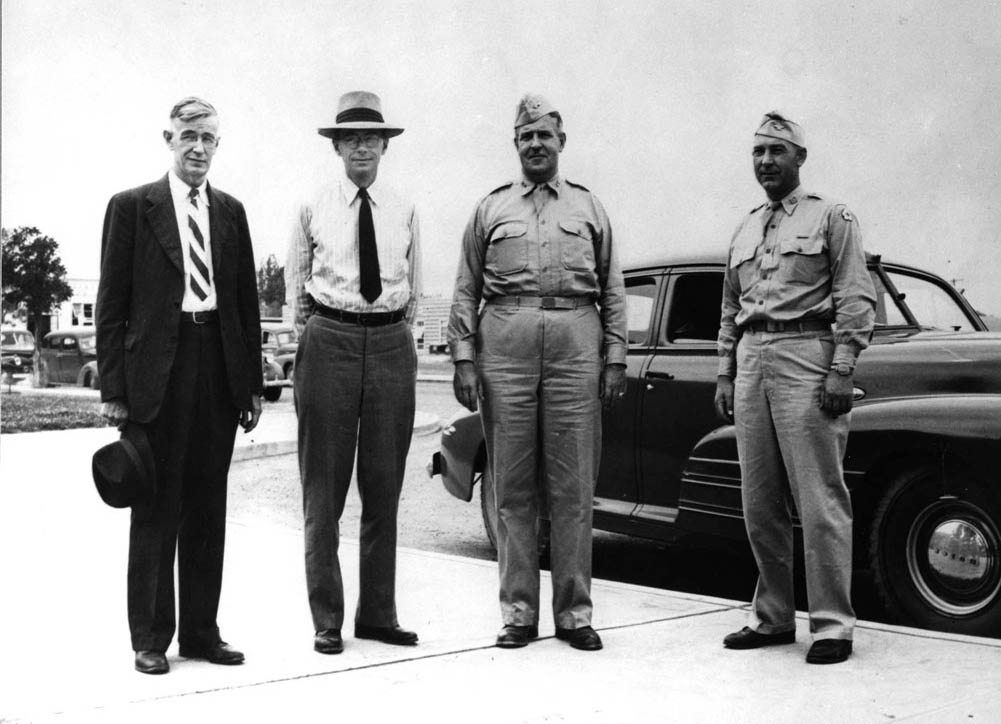

September 1942: General Leslie Groves Takes Charge

Named the director of the Manhattan Project in September 1942, Army Corps of Engineers General Leslie R. Groves had already overseen a million men and spent $8 billion (four times the cost of the Manhattan Project). Groves had been in charge of managing the Army’s mobilization for World War II, including the construction of camps, air bases, munition plants, hospitals, and the Pentagon.

Not one to waste time, Groves immediately focused on the Manhattan Project’s need for appropriate sites to develop the world first’s atomic bomb. The project needed hundreds of acres of land with sufficient resources and enough isolation to protect its secrecy.

While isolation was an important selection criterion, finding completely isolated sites that also had access to transportation, a nearby labor force, and other resources was impossible. When the land along the Columbia River was selected for the Hanford reservation, local residents were forced to abandon their homes and land. Displacement came with economic and emotional repercussions, and the operations that followed led to long-term environmental consequences for the area.

“Like a Bombshell”

Hanford was selected for its abundance of water for hydroelectric power, rural isolation and long construction season. The area’s proximity to the Grand Coulee and Bonneville Dams on the Columbia River was ideal for hydroelectric power. For the Hanford site, the United States government requisitioned about 580,000 acres, equivalent to about half of Rhode Island.

In early 1943, there were some 2,300 people living in the towns of Hanford, White Bluffs and Richland and unincorporated agricultural lands along the Columbia River. Residents were given anywhere from twenty-eight days to ninety days’ notice to vacate their homes. Because of secrecy, the government vaguely explained to residents that the land was needed for a new military wartime project. The “Notice of Exclusion” sent to Paula and Ludwig Bruggemann’s father, a fruit farmer in White Bluffs, demonstrates the ambiguous language of these War Department notices:

“To: Paul Ludwig Bruggemann

“To: Paul Ludwig Bruggemann

Attached hereto is a copy of Public Proclamation No. 18, dated July 14, 1943, by Headquarters, Western Defense Command and Fourth Army, Presidio of San Francisco, California.

You, PAUL LUDWIG BRUGGEMANN, are hereby notified that your presence in Total Exclusion Area No. 3 violates the provisions of Public Proclamation No. 18; and you are hereby further notified and directed to leave Total Exclusion Area No. 3 by September 30, 1943.

By Order of the District Engineer: F. T. Matthias, Lt. Col., Corps of Engineers, Deputy District Engineer, Manhattan District.”

In his interview on the Voices of the Manhattan Project website, Walt Grisham explains what his family’s farm was like before the government requisitioned the land for the Manhattan Project. According to Grisham, his family farm had two acres of grapes, four acres of apricots, seven acres of peaches, a small patch of asparagus, alfalfa hay, and pasture and row crops. They also had cows, chickens, and Duroc hogs. Describing their lifestyle, he said that “they didn’t run to town for a quart of milk or a dozen eggs in those days. It was kind of a self-supporting, diversified situation, where you were pretty much on your own.”

When Grisham learned that his family was being forced off of their farm and land by the government, he was abroad in England serving in the U.S. Air Force. He explained that his family along with others were “given a deadline and that was it. No assistance in how to get there or how to leave. It became a real tough situation.” The stress was so great, Grisham remembered, that his “mother had a stroke in the process of moving.”

While compensation was provided to the families and farmers in exchange for the land, residents found the government’s appraisal and subsequent compensation greatly insufficient. Grisham noted that in the appraisal given to his family at the time “there was no mention on the appraisal of buildings. No buildings. No irrigation system. No fences were listed on the appraisal that they had.” To Grisham, the exclusion of these features and the family’s orchards never made sense because they “constitute a major value, as far as a farm is concerned.”

Arguing the government was undervaluing their property, many families took the government to court in hopes of getting a more favorable appraisal. In an interview with S. L. Sanger, local lawyer Lloyd Wiehl recounted the shock of the government’s actions and appraisals: “It came like a bombshell. They announced they were taking the whole valley. For what? We didn’t know. At that time, the farmers were short of money and didn‘t have any place to go, really.”

According to Wiehl, the government made such low appraisals because “they brought in Federal Land Bank people from clear out of the state, like Montana or elsewhere. They didn’t understand the valley or fruit, and they didn’t think much of the valley.” With the help of Wiehl, many of the farmers were able to get their property reappraised and settle with the government for greater compensation out of court. General Groves’ Officer-In-Charge at Hanford, Colonel Franklin T. Matthias, realized settling outside of court would save time, which was more pressing than money during the war.

Native American Tribes Seek Visitation Rights

While farmers and other local residents received at least some compensation, the Native American tribes, who frequented the area for fishing, hunting, and ceremonial purposes, received no compensation. Native Americans were the first known inhabitants of the Columbia Basin, an ideal spot for salmon fishing, hunting, and living. During the wintertime, the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, the Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation, and the Nez Perce Tribe lived in the Columbia Basin, while the Wanapum Tribe lived there year-round.

.jpg)

Russell Jim, a member of the Yakama people and head of the Confederate Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation, told the Atomic Heritage Foundation in an interview that his people “lived in harmony with the area, with the river, with all of the environment. All the natural foods and medicines were quite abundant.” The Yakama previously used Hanford and the Columbia Basin area for their wintering grounds.

Similar to the views of farmers in the area, Russell Jim explained how he imagined Manhattan Project leaders saw the area: “The area was an isolated wasteland, and the people were expendable. And that was in writing. And therefore the Manhattan Project was justified here, and everyone was moved out, including the Yakama Nation people.” With the government’s requisition of the land for the Manhattan Project, the Wanapum tribe who lived on the land permanently were forced to resettle in Priest Rapids.

Although they received no compensation for the land, the tribes were given visitation rights that allowed them to camp, hunt or fish in the Hanford area. Wanapum Chief Johnny Buck met with Colonel Matthias to negotiate his tribe’s rights. In an interview with S. L. Sanger, Matthias remembered telling Buck that he would “arrange to take your people up to the White Bluffs island every morning by truck to do your fishing. We’ll bring you back by night or in some cases maybe you can stay there overnight.”

Issues with this arrangement soon arose. According to Atomic Spaces: Living on the Manhattan Project, Buck sent a letter to Matthias to “detailing the Manhattan District’s failures” in the winter of 1943 (Hales, p. 205). The result was a meeting at the Wanapum’s Spring Festival on April 2, 1944. In an agreement with Buck, Colonel Matthias arranged for a series of passes to be issued to the tribe (Hales, p. 205). Later, in the 1957 case Satiacum v. Washington (314 P.2d 400), the Washington Supreme Court ruled that the State must recognize Native American fishing rights (Murphree, ed., 1210).

Legacy of Displacement

Besides having to relocate, local residents experienced environmental and emotional repercussions. Visiting his family’s farmland years later, Grisham was grim: “You don’t see very much right now. You see a lot of cheat grass.” This sight was a sharp contrast to sixty years previously when there were fruit orchards and crops growing on the farm.

During World War II, soldiers and civilians made many sacrifices. In the case of the residents of Hanford, they gave up their homes and land for construction of Manhattan Project facilities. Gabriel Bohnee, who works for the Nez Perce’s Environmental Restoration and Waste Management Office, addresses the long-term impact: “The environment was sacrificed in the name of global power.”

When asked about his feelings on being displaced from his Hanford home, Grisham expressed disappointment rather than bitterness. Rather than question the importance of the Manhattan Project, Grisham found issue with how the Manhattan Project took over his community. His disappointment stemmed from feeling that he and his family were unfairly harmed in the urgency of the construction process.

Interpreting the History

On November 10, 2015, the National Park Service (NPS) and the Department of Energy (DOE) signed an agreement that officially established the Manhattan Project National Historical Park with units at Oak Ridge, TN, Hanford, WA, and Los Alamos, NM. The agreement provided a division of roles in managing the new park. The NPS is the “storyteller” responsible for interpreting the Manhattan Project while DOE must maintain its properties that are part of the park.

After convening meetings with scholars and the public, NPS published four major interpretive themes for the park. The first theme highlights displacement: “The “secret cities” created by the Manhattan Project, and the sacrifice and displacement connected to them, exemplified this massive wartime effort demonstrating remarkable opportunities to reflect on the extraordinary lengths to which people and nations go to protect their futures.”

After convening meetings with scholars and the public, NPS published four major interpretive themes for the park. The first theme highlights displacement: “The “secret cities” created by the Manhattan Project, and the sacrifice and displacement connected to them, exemplified this massive wartime effort demonstrating remarkable opportunities to reflect on the extraordinary lengths to which people and nations go to protect their futures.”

Through personal accounts, visitors can gain insight into the Manhattan Project’s impact on the agricultural settlers who lost their homes, farms, and communities along the Columbia River and the Native Americans who lost access to their camping, hunting, fishing and sacred lands. Below is a list of people who were displaced from the Hanford reservation who shared their perspectives.

The Atomic Heritage Foundation’s “Ranger in Your Pocket” program on “Hanford’s Pioneers” includes first-hand accounts from displaced families and members of Native American Tribes at Hanford. Click here to watch the program.

For more information about visiting the Manhattan Project National Historical Park, please click here.

List of Oral Histories

- Gabriel Bohnee

- Paula and Ludwig Bruggemann

- Frank Buck

- Rex Buck

- Walt Grisham

- Annette Heriford

- Kathleen Hitchock

- Russel Jim

- Colonel Franklin T. Matthias

- C. Marc Miller

- Veronica Taylor

- Lloyd Wiehl

united states government no trespassing sign_1.jpg)