The debate over what precipitated the Japanese surrender at the end of World War II is a source of contention among historians. This debate has also figured prominently in the discussion of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki (for more on that discussion, see Debate over the Bomb). The “traditional narrative” put forward in the war’s immediate aftermath was that using the atomic bombs caused the surrender, but this narrative has come under fire in subsequent years.

As with other debates around the Manhattan Project, ambiguities arise due to the fact that many of the available primary sources are considered unreliable. The historians who have tackled this issue have generally used the same pool of primary source information, but they have come to divergent conclusions because they differed in which sources they considered trustworthy or significant.

Traditionalist School

The “traditionalist school” accepts the explanation given by President Truman, Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson, and others in the government in the aftermath of the war. The traditionalist conception is that the atomic bombs were crucial to forcing Japan to accept surrender, and that the bombings prevented a planned invasion of Japan that might have cost more lives. Emperor Hirohito’s citation of the “new and most cruel bomb” in his speech announcing surrender bolsters this theory’s credibility.

Historians have critiqued various parts of this rationale for the bombings, including casualty estimates from the planned invasion. Retrospective estimates vary wildly, and are often lower than the figures stated by Truman and Stimson. But there is also a sizable literature disagreeing with the central premise: that the bombs led to the surrender.

Revisionist School

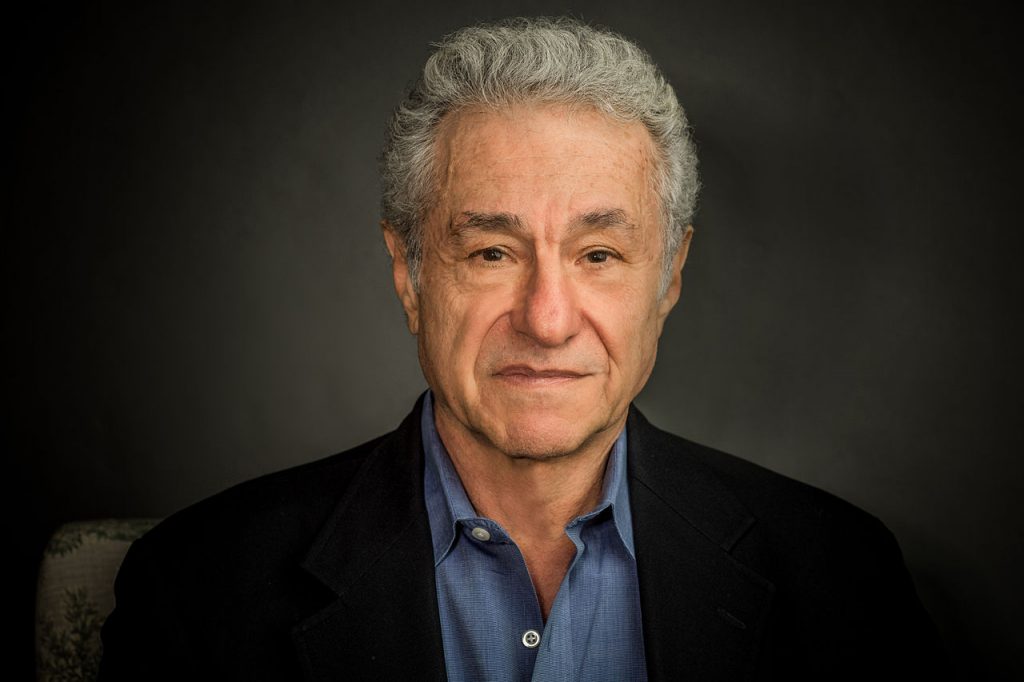

The oldest and most prominent critics of the traditionalist school have been the “revisionist school,” starting with Gar Alperovitz in the 1960s. The revisionists argue that Japan was already ready to surrender before the atomic bombs. They say the decision to use the bombs anyway indicates ulterior motives on the part of the US government. Japan was attempting to use the Soviet Union to mediate a negotiated peace in 1945 (a doomed effort, since the Soviets were already planning on breaking off their non-aggression pact and invading). Revisionists argue that this shows the bombings were unnecessary.

The oldest and most prominent critics of the traditionalist school have been the “revisionist school,” starting with Gar Alperovitz in the 1960s. The revisionists argue that Japan was already ready to surrender before the atomic bombs. They say the decision to use the bombs anyway indicates ulterior motives on the part of the US government. Japan was attempting to use the Soviet Union to mediate a negotiated peace in 1945 (a doomed effort, since the Soviets were already planning on breaking off their non-aggression pact and invading). Revisionists argue that this shows the bombings were unnecessary.

The other piece of evidence behind this claim is the US Strategic Bombing Survey, conducted after the war. It concluded that Japan would have surrendered anyway before November (the planned start date for the full-scale invasion). Some historians have identified flaws in the survey, based on contemporary evidence. Others have argued that the US had no reason to trust the sincerity of the Japanese outreach to the Soviets, and that evidence from within Japan indicates that the Japanese Cabinet was not fully committed to the idea of a negotiated peace.

Revisionists have also contended that surrender could have happened without the bombings if the US had compromised on its goal of unconditional surrender. The sticking point for the Japanese was retaining the emperor in his position. It is unclear if they would have accepted the reduction of the emperor to a figurehead, as eventually happened after the war. Many officials advocated for maintaining the emperor’s authority as a condition for surrender even after the Hiroshima bombing.

The Soviet Invasion

.jpg) Another school of thought dismisses parts of both the traditionalist and revisionist theories, emphasizing instead the Soviet invasion of Japan-controlled Manchuria. The most prominent proponent of this theory is Tsuyoshi Hasegawa, who has argued that the invasion was far more important than the bombs in contributing to the surrender. Hasegawa’s arguments are partly based on chronology: the Japanese government made important decisions about surrender after the invasion, rather than after the Hiroshima bombing three days earlier. The Nagasaki bombing, by all accounts, did not change their calculus very much. Also, while the emperor cited only the atomic bomb in his speech to the people, a later rescript addressing troops mentioned the invasion specifically.

Another school of thought dismisses parts of both the traditionalist and revisionist theories, emphasizing instead the Soviet invasion of Japan-controlled Manchuria. The most prominent proponent of this theory is Tsuyoshi Hasegawa, who has argued that the invasion was far more important than the bombs in contributing to the surrender. Hasegawa’s arguments are partly based on chronology: the Japanese government made important decisions about surrender after the invasion, rather than after the Hiroshima bombing three days earlier. The Nagasaki bombing, by all accounts, did not change their calculus very much. Also, while the emperor cited only the atomic bomb in his speech to the people, a later rescript addressing troops mentioned the invasion specifically.

Hasegawa also has focused on trying to parse the decision-making process within the Japanese Cabinet. He argues that the Japanese were somewhat accustomed to bombing after the firebombing of numerous cities, including Tokyo. The atomic bombs were, to them, simply an escalation in scale, not an entirely new threat. He also asserts that Japan would have considered the Soviet invasion a bigger shock because of the underlying betrayal. The Japanese were also motivated, according to Hasegawa, by the desire to not allow the Soviets to have a hand in the post-war process. The aristocratic government feared the Soviet Union might foment―or directly bring about―a communist overthrow of their power structure.

Hasegawa’s theory has gained popularity, with a notable convert being Pulitzer Prize winner Richard Rhodes, but it is far from universally accepted. Critics have alleged that his methodology involves too much guesswork and that he interprets sources too liberally.

Internal Politics

Another theory differs slightly from the traditionalist narrative. Some scholars still see the bomb as decisive. But they see it as an excuse for the Japanese leadership to end the war without facing an internal challenge. Herbert P. Bix, whose award-winning biography of Hirohito focused on internal Japanese records, contends that in 1945 many Japanese leaders were in a state of paranoia about a possible internal uprising. Especially after the government’s strictures against surrender, the emperor and his Cabinet worried about the consequences of capitulating. They were especially afraid of leftists or communist agitation. Despite the country’s strong nationalism, the 1940s had produced some general discontent because of rationing, bombings, and other wartime exigencies.

Another theory differs slightly from the traditionalist narrative. Some scholars still see the bomb as decisive. But they see it as an excuse for the Japanese leadership to end the war without facing an internal challenge. Herbert P. Bix, whose award-winning biography of Hirohito focused on internal Japanese records, contends that in 1945 many Japanese leaders were in a state of paranoia about a possible internal uprising. Especially after the government’s strictures against surrender, the emperor and his Cabinet worried about the consequences of capitulating. They were especially afraid of leftists or communist agitation. Despite the country’s strong nationalism, the 1940s had produced some general discontent because of rationing, bombings, and other wartime exigencies.

Bix argues that the emperor and the Cabinet saved face by declaring that they were surrendering in order to prevent further atomic bombings. This explanation helps to rationalize an apparent contradiction between the emphasis on saving Japanese lives in Hirohito’s radio broadcast and the government’s previously cavalier attitude toward their own civilian population. In the months before surrender, the Japanese government had ramped up the amount of kamikaze attacks. Just days before the final decision, they had been arming citizens with bamboo sticks to fend off a land invasion.

Bix posits that the bombs’ impact was not that they shocked the Japanese into giving up (he agrees with Hasegawa on this point), but that they allowed for the completion of a surrender process that was already desired. As with other theories above, this argument relies on guessing the thought process of the Japanese leaders.

The Nagasaki Question

In discussions of surrender, two key events dominate discussion: the bombing of Hiroshima, and the Soviet invasion. The bombing of Nagasaki, a few hours after the Japanese government learned of the Soviet advance, does not get much attention. Official reports and personal recollections from the Japanese government indicate that Nagasaki had little effect on decision-making. Critics of the bombings have asked why a second bomb was dropped at all, especially after such a short window of time.

Nuclear historians Alex Wellerstein and Michael Gordin have argued that this question is flawed, because the plan was originally to drop more than two atomic bombs on Japan. Manhattan Project figures, including J. Robert Oppenheimer and General Leslie Groves, and military planners such as General John E. Hull assumed that at least two bombs would be needed. Truman did not even give an explicit order about the bombs until after Nagasaki, when he put a moratorium on their use. Because of this, Wellerstein contends, “Why did they stop with Nagasaki?” is a more historically appropriate question than “Why did they bomb Nagasaki?”

A “Knockout Punch”?

With the shakiness of the evidence available, it is impossible to say for certain what caused the Japanese surrender. It is also impossible to prove counterfactuals about what would have happened if events had transpired otherwise. The schools of thought outlined here have coalesced around certain, oppositional interpretations of events. But the truth may lie somewhere in the middle. A new school, sometimes referred to as the “consensus school,” has sought to reconcile parts of the traditionalist and revisionist perspectives, both about the motivation behind the bombing and the reasons for surrender. Even Hasegawa, a fervent opponent of the traditional narrative, has admitted that the Soviet invasion did not deliver a “knockout punch” that lead to immediate surrender. It seems like there is no easy answer to the questions surrounding surrender, and historians will continue to debate the issue.