The Manhattan Project in Japan

Manhattan Project members participated in early missions to survey the two atomic bombing sites—Hiroshima and Nagasaki—after the Japanese surrender in August 1945. The Manhattan Project’s representatives were led by General Leslie Groves’s deputy, General Thomas Farrell.

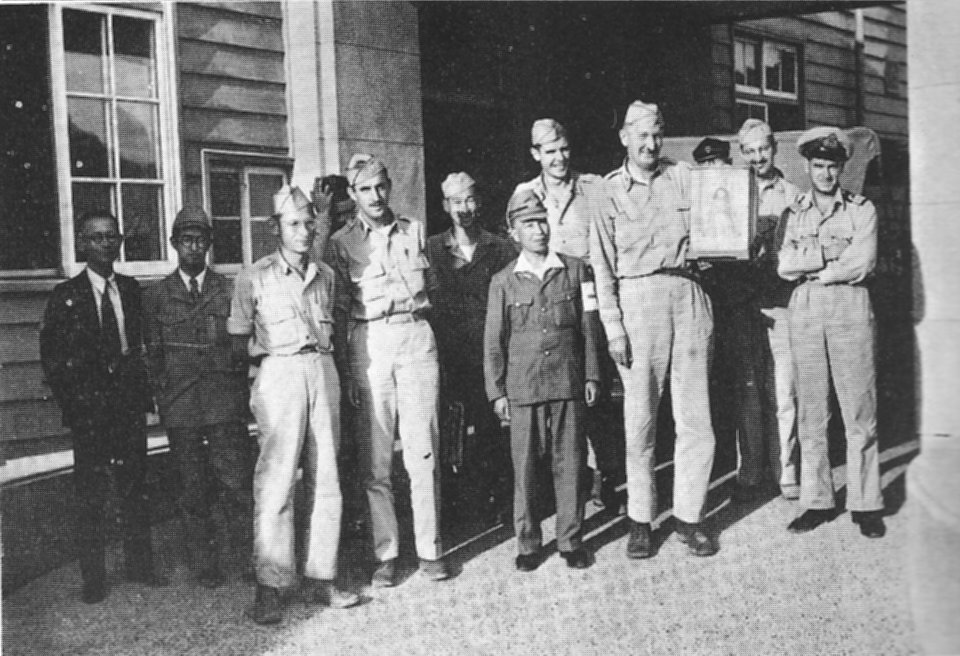

They arrived in Tokyo on September 1, 1945. Farrell brought along members of the Army Air Forces, and they also worked with Japanese scientists who served as interpreters and helped with data collection.

Farrell had originally organized two groups, led by Colonel Stafford Warren and Captain Hymer Friedell, to go to Nagasaki and Hiroshima, respectively. Warren and Friedell were both medical officers and radiation experts. A special early group, led by Farrell himself, entered Hiroshima on September 8.

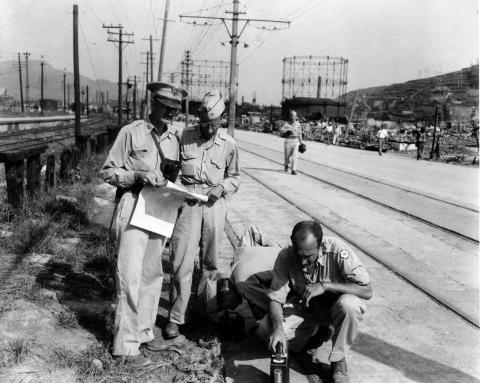

The Manhattan Project members were joined by others from the International Red Cross, the Army Medical Corps, and the staff of General Douglas MacArthur. They took readings with Geiger counters and photographs of the destruction caused by the bomb. Warren and Friedell’s teams proceeded afterwards. Warren’s arrived in Nagasaki on September 17, but Friedell’s was delayed by weather and arrived on September 26, giving them little more than a week to complete their survey.

In her interview on the Atomic Heritage Foundation’s Voices of the Manhattan Project website, Los Alamos “computer” Jean Bacher recalled conversing with Philip Morrison, one of the Los Alamos scientists who traveled to Hiroshima and Nagasaki. She described Morrison and other Japan surveyors from Los Alamos as “appalled and just stunned” at what they saw in Japan. After listening to Morrison’s recounting of the devastation, Bacher described feeling “absolutely undone” and unable to sleep.

The Manhattan Engineer District’s Report

On June 29, 1946, the Manhattan Engineer District published a report, The Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which detailed their observations from the survey visits to Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In the report, the Manhattan Project personnel outlined the effects of the atomic bombs on these two cities by compiling their observations and data regarding “damage to structures, injuries to personnel, morale effect, etc.” The hope was that this survey would provide scientific, technical and medical intelligence from Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

The report explained that damage to the cities from the bomb had two main causes: the blast (and pressure) of the explosion and fires. There were three types of categories for fires: primary fires (those from the bomb’s heat), secondary fires (those from collapse or damage to infrastructure), and fires that came from the original fires.

The report found four major causes of casualties in Hiroshima and Nagasaki: flash burns (immediate burns from the bomb’s heat and light), burns from fires, injuries from infrastructure collapse, flying debris or the bomb’s pressure waves, and radiation injuries from instantaneous penetration of gamma radiation from the bomb.

Significantly, the report concluded that the cities did not possess harmful levels of persistent radioactivity after the explosions. The evidence for this conclusion was based on measurements of the intensity of radioactivity in the cities and a lack of clinical evidence of people harmed by persistent radioactivity.

At the end of the report, the Manhattan Project workers also noted the observed psychological effects on survivors and demonstrated this feeling of terror by including an eye-witness account in the appendix.

U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey’s Report

The Manhattan Project teams were not the only survey teams sent to the bomb sites, though they were the first. They were followed by others, such as the US Strategic Bombing Survey (USSBS), established by the War Department specifically for the purpose of post-war surveying. Members of the USSBS testified before Congress about the effects of the atomic bombs, as did Farrell and Warren (though the different survey teams disagreed on multiple points about the bombs’ impact).

On June 19, 1946, the USSBS published a report, The Effects of the Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which addressed the observations and results of the USSBS surveys in Japan. The survey team included 300 civilians, 350 officers and 500 enlisted men with 60% from the Army and 40% from the Navy. In nine months, the USSBS “interrogated more than 700 Japanese military, government and industrial officials” about the atomic bombings and their effects in Japan.

The USSBS also surveyed civilians about their opinions on Japan’s status in the war before and after the bombs had been dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. While a majority of people had doubts about Japan’s victory prior to the bombs being dropped, an additional 28% thought victory was impossible following the atomic bombings.

The survey also reported that 40% of people reported a feeling of defeatism post-bombing. This number was higher in Hiroshima than Nagasaki, which the USSBS concluded was due to the more severe damage in Hiroshima.

Like the Manhattan Engineer District’s report, the USSBS report included an assessment of the damage and casualties from the bomb. The USSBS report also featured a section on how the atomic bomb works, and concluded by addressing the hypothetical atomic bombing of major U.S. cities.

Investigating Japan’s Atomic Progress

Not all the Manhattan Project members sent to Japan were looking specifically at the bombs’ effects. General Groves assigned a special task to Major Robert Furman, who had participated in the Europe-based Alsos Mission: to determine whether Japan had made its own steps towards an atomic bomb. In his interview on the Atomic Heritage Foundation’s Voices of the Manhattan Project website, Furman recalled going to “the universities and all the factories in Japan and Korea looking for any trace of nuclear action.”

Furman explained that universities were identified as potential sources because they knew that “if there was a project, the scientists had to come from the universities.” Specifically, their group knew of about “eight Japanese scientists who had studied in Germany and were possibly capable of running a project if Japan had one.”

Besides investigating universities, Furman described going to big corporations in Japan and Korea to inquire about their personnel, facilities, and research departments. Furman’s group traveled to Korea because it had mineral resources, which would be a starting point for nuclear research. They particularly wanted to see if there was any “mining of uranium, thorium, or radium.” He concluded that, though there had been some initial attempts at researching atomic weapons, there was “no serious project” in Japan.

While the Japanese military did invest in atomic bomb research, they were neither able to enrich enough uranium nor able to develop the required detonation technology for an atomic weapon. For more information on Japan’s atomic bomb research, click here.