Stafford Leak “Staff” Warren was a Colonel in the Army Medical Corps and the Chief Medical Officer of the Manhattan Engineer District (MED). He also participated in the Trinity Test, early surveys of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and Operation Crossroads.

EARLY LIFE AND RECRUITMENT

Warren was born in Maxwell City, New Mexico, in 1896. His family had moved to the West two generations prior when his grandfather joined the California Gold Rush. He attended the University of California, Berkeley, and then got his medical degree from University of California, San Francisco. While in medical school, he married Viola Lockhart, a classmate from Berkeley. During the 1920s, the couple went on a trip to Europe, where they met some of the early European pioneers of nuclear science, including Marie Curie. They had three children together: Dean, Roger, and Jane.

After postdoctoral work at Johns Hopkins and Harvard, he joined the Department of Radiology at the University of Rochester’s new School of Medicine and Dentistry in 1926. He made contributions to the field of radiology that included taking a color video of live cancer cells, pioneering the “fever treatment” for gonorrhea, and creating an early iteration of the mammogram.

In early 1943, after a countrywide search, General Leslie Groves decided that he wanted Warren to be the Chief Medical Officer for the Manhattan Project. According to Colonel James Marshall, they had been convinced of the need for a medical official by the story of women who had died after spending World War I painting radium dials. Groves had considered scientists already involved in the project, such as Robert Stone at the University of Chicago. He settled on Warren, however, who had gained national renown for his work in radiology.

In March, Warren was invited to coffee with Groves, Marshall, and Eastman Kodak official Albert Chapman (Eastman was a Manhattan Project contractor based in Rochester). After coffee, he was whisked to a locked room by the two military men, who explained to him the vague outlines of their secret project. He was not the only one who had to be convinced: Groves had to press Rochester President Alan Valentine to release Warren to military service. He originally signed on in an advisory role, and briefly headed Rochester’s Atomic Energy Project, before his commission in the Army Medical Corps was approved.

MANHATTAN PROJECT INVOLVEMENT

After being commissioned as a Colonel, Warren and his wife moved down to the Oak Ridge site in June 1943. His deputy was Captain Hymer Friedell, who had previously handled medical affairs for the MED. Unlike some of the academics who joined the military as part of their wartime work, Warren relished his Army appointment. He even reportedly showed up to his first day of work at Oak Ridge wearing combat boots. His military-oriented outlook led to clashes with Stone, still the head of the Chicago Met Lab’s Health Division. They disagreed over whether the focus of their efforts should be on near-term wartime needs or long-term learning, and about the principle of military oversight.

When he arrived at Oak Ridge, the project was desperately understaffed in terms of health professionals. He enlisted outside organizations for recruiting help, including the Office of the Surgeon General (OSG). Warren arranged a special relationship between the MED and the OSG, where the latter organization agreed to help by commissioning and training civilians. At the same time, it allowed the MED to maintain its independence and secrecy. Another early concern for Warren was organizing the MED’s Medical Division. The men under Warren’s command ended up with three major tasks: research, clinical medicine, and industrial medicine (which eventually evolved to mainly cover radiation hazards).

Plutonium emerged as a major problem. Little was known about the new element and how it affected the human body. Warren was linked to the controversial human plutonium injection experiments that originated from the Manhattan Project. When questioned later, he said he had not opposed the experiments, but had not been directly involved either.

During the course of the Manhattan Project, Warren traveled (usually with Friedell) to many different sites: Berkeley, Chicago, Hanford, Los Alamos, and back to Rochester. At Chicago, early on in his tenure, he assisted with the creation of concrete shielding for Chicago Pile-1. He traveled to Los Alamos in August 1944 to meet with Health Group leader Louis Hempelmann following Don Mastick’s plutonium accident. He approved Hempelmann’s plan for biological research at Los Alamos. He also had to deal with every sort of medical concern at Oak Ridge, including insect control and worker nutrition. In addition, he personally advised General Groves on medical issues.

One of Warren’s challenges was handling the medical research leaders at all the different sites, each of whom had his own goals and personality. Medical professionals were not Warren’s only worry, however. He also had to see that standards were obeyed by all the contractors who handled radioactive or other hazardous materials. Often contractors were less cooperative than project staff.

1945: TRINITY AND JAPAN

In 1945, Warren spent more time in New Mexico, assisting Hempelmann and Captain James Nolan with safety planning for the Trinity Test. He witnessed the “100-Ton Shot” that preceded Trinity, and assisted in preparations such as doing an aerial survey of the area and, along with Nolan, drawing up an evacuation plan. Warren was especially concerned about the effect that thunderstorms might have on radioactive fallout. Groves initially dismissed the evacuation plan, citing security concerns, but eventually agreed to station troops in neighboring towns as a precaution. Groves later recounted being angry that Warren had not slept in the 48 hours preceding the test.

Warren observed the test itself, and remained in contact by phone with Friedell, who was prepared to take over in case of tragedy. After the test went off, many of the scientists observing reacted with relief or astonishment. Warren’s words to Friedell on the phone were simply, “All is well.” Warren’s work did not stop there. He directed teams that had been sent out to measure radiation around the site. Warren advocated banning further testing at the Trinity site, leading to a search for a less populated area.

In September 1945, after the end of the war, Warren went to Hiroshima and Nagasaki to investigate the bombs’ effects. He went on the rushed initial visit to Hiroshima, where, as one of the first military officers to enter the city, he received a sword from the city’s garrison commander. Years later, he went back to Japan to return the sword to the commander’s family. A few weeks after going to Hiroshima, he headed a more extensive mission to Nagasaki. In Japan, he worked closely with Ashley Oughterson, a surgeon on General Douglas MacArthur’s staff. The investigation groups also had assistance from Japanese scientists who served as interpreters.

Warren’s surveys concluded that residual radiation was not a major problem, and attributed most cases of radiation sickness to the bomb’s initial gamma-radiation burst. Warren’s conclusion was certainly off, given what is known now about the radioactive fallout from nuclear detonations, and about the casualties in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Some, such as historian Eileen Welsome, have cast Warren’s inaccuracies as deliberate misinformation, designed to downplay the destructive effects of the atomic bombs.

Warren testified about the radiation effects before Congress in February 1946, where he also contradicted the conclusions of the Strategic Bombing Survey. The Survey was conducted by the War Department to determine the effects of various type of bombs on Japan. It famously concluded that Japan would have surrendered even if the atomic bombs had not been dropped, fueling a fervent debate. Warren’s testimony mainly supplemented that of General Thomas Farrell, who argued that the Survey had underestimated both the psychological toll of the atomic bombs and their equivalent in conventional bombing.

The time in Japan clearly affected Warren, as he avoided talking about his experiences later in life, even with his family. He did not, however, question the bombings themselves. “We considered Hiroshima a surgical operation,” he later said. “With so much killing going on, we didn’t worry about the ethics of killing more.”

CROSSROADS AND AFTER

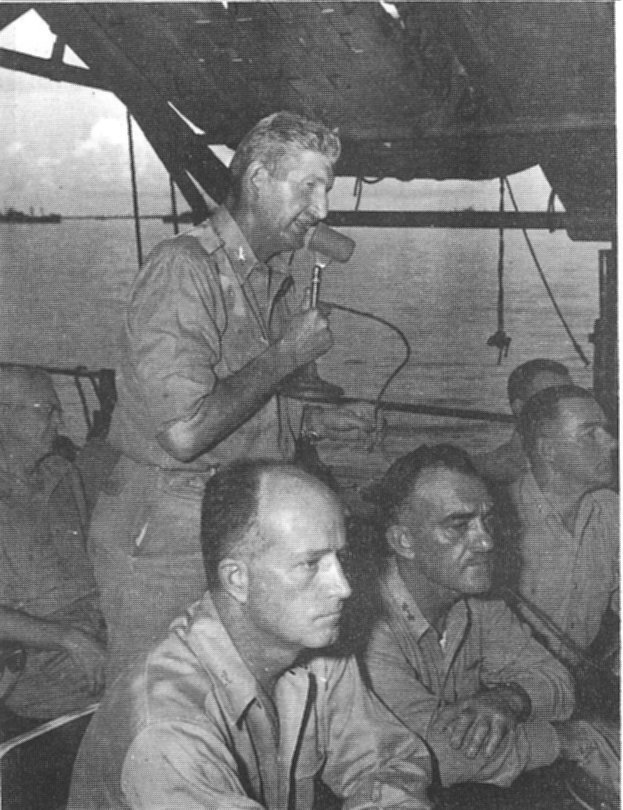

Warren was placed in charge of safety for the Operation Crossroads nuclear testing in the Pacific. His letters to his wife provide a good account of what went on at Bikini Atoll. The military initially underestimated the manpower needed for adequate precautions and testing. Warren tried desperately to recruit qualified colleagues, even pressing his son Dean into joining. He also formed a Medico-Legal Board to ensure that proper safety procedures were taken and to prevent the military from being liable for any accidents.

The first test, Shot Able, went off without a hitch. But the second, Shot Baker, caused more persistent levels of high radioactivity. The animals placed on the ships in the fallout zone had extremely high mortality. Several ships anchored at the atoll were supposed to have been decontaminated, but levels of radiation were so high that the effort was abandoned. Warren also had trouble gaining cooperation from Navy officers, who often ordered their men into unsafe situations. Eventually, Warren urged an accelerated conclusion to Crossroads, contributing to the cancellation of the third planned test. Afterward, he said, “I never want to go through the experience of the last three weeks of August again.”

After Crossroads, he began a crusade to inform the public about the dangers of fallout, especially its effect on the environment. This included a series of speeches and an article in LIFE magazine in August 1947, one of the earliest articles for the public about fallout. It concluded with the ominous lines: “The only defense against atomic bombs still lies outside the scope of science. It is the prevention of atomic war.” Some of his fellow scientists and Manhattan Project veterans resented his crusade. Warren’s successor at the MED, James Cooney, blamed him later for overblown public hysteria about fallout.

After retiring from the military in November 1946, he became the founding dean and a professor of biophysics at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) Medical School, and later Vice Chancellor of Health Services. Under his tenure, the school rose from the ground up, from temporary structures left over from the war to a world-class institution. He started an Atomic Energy Project at UCLA, modeled on the one at Rochester, and built the first nuclear reactor for medical purposes.

After leaving UCLA, he became a consultant to the US Public Health Service, and advised Presidents Kennedy and Johnson on mental disabilities. His wife died in 1968, and he married Gertrude Turner Huberty in 1970. He received the prestigious Enrico Fermi Award from the Department of Energy in 1971.

Warren died in 1981 in the Pacific Palisades neighborhood of Los Angeles. All of his papers, including those from during the war, are available at UCLA Library.