The Bombings

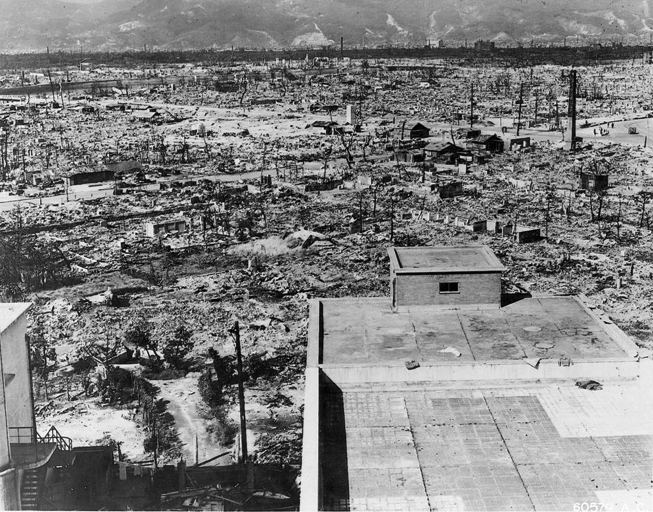

On August 6, 1945, the United States dropped its first atomic bomb, a uranium gun-type bomb nicknamed “Little Boy,” on Hiroshima. It exploded with approximately 15 kilotons of force above the city of 350,000, causing a shockwave of destruction and a fireball with temperatures as hot as the sun.

Kimura Yoshihiro, in third grade at the time, saw the bomb fall from the plane. “Five or six seconds later, everything turned yellow. It was like I’d looked right at the sun. Then there was a big sound a second or two later and everything went dark” (Rotter 197). Those at the epicenter of the blast were vaporized instantly. Others suffered horrific burns or were crushed by falling buildings. Hundreds threw themselves into the nearby river to escape the fires that burned throughout the city. As Doctor Michihiko Hachiya recalled, “Hiroshima was no longer a city, but a burnt-over prairie” (199). Sadako Kurihara also expressed the aftermath in her poem “Ruins” (226):

Hiroshima: nothing, nothing-

old and young burned to death,

city blown away,

socket without eyeball.

White bones scattered over reddish rubble;

above, sun burning down:

city of ruins, still as death.

Three days later, the United States dropped a second bomb, a plutonium implosion bomb called “Fat Man,” on Nagasaki, home to an estimated 250,000 at the time. Koichi Wada, two miles away from ground zero, remembered, “The light was indescribable – an unbelievably massive light lit up the whole city.” Sumiteru Taniguchi, fourteen at the time, was blown completely off his bicycle by the force of the blast. “The earth was shaking so hard that I hung on as hard as I could so I wouldn’t get blown away” (Southard 43). Katsuji Yoshida, only a half mile from the explosion, recalled, “Blood was pouring out of my flesh. I know it sounds strange, but I felt absolutely no pain. I even forgot to cry” (48). You can watch testimonials from survivors here. To read more accounts from the survivors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, click here.

The Japanese military quickly sent a three-member documentary crew to record the bombings for possible propaganda use, though there would be too much chaos to use the footage. Yamahata Yosuke, the photographer on the team, remembered, “One blessing among these unfortunate circumstances is that the resulting photographs were never used by the Japanese army… in one last misguided attempt to rouse popular support for the continuation of warfare” (79).

The surrender of Japan was announced on August 15, six days after the bombing of Nagasaki. The end of the war disenchanted the survivors. Nagasaki resident Seiji Nagano recalled, “‘Why?’ we asked. ‘After everything we did to try to win the war! What purpose did it serve? So many people died. So many homes have burned down. What will we do now? What will we do? What will we do?’” (95).

Immediate Aftermath

In the days after the bombings, families in Hiroshima and Nagasaki were advised to leave the cities. Some left with what little provisions they could find, but many had nowhere to go. They made primitive huts on the edge of the cities, or slept in train stations and burned-out train cars.

Meanwhile, symptoms of radiation poisoning began. These included hair loss, bleeding gums, loss of energy, purple spots, pain, and high fevers, often resulting in fatalities. Rumors quickly spread that the mysterious illness was contagious. Hibakusha were turned away from homes, and some farmers even refused to give them food. The Japanese government’s report on August 23 describing radiation poisoning as an “evil spirit” did not help the situation (Hogan 133). It would not be the last time the hibakusha faced discrimination.

Although Japanese doctors began to guess that the outbreak of illness was caused by radiation, they had little means for treatment or research. Doctor Tatsuichiro Akizuki compared it to the Black Death of the Middle Ages: “Life or death was a matter of chance, of fate, and the dividing line between the man being cremated and the doctor cremating him was slight” (Southard 99).

Although Japanese doctors began to guess that the outbreak of illness was caused by radiation, they had little means for treatment or research. Doctor Tatsuichiro Akizuki compared it to the Black Death of the Middle Ages: “Life or death was a matter of chance, of fate, and the dividing line between the man being cremated and the doctor cremating him was slight” (Southard 99).

The United States, whose knowledge of radiation poisoning was only marginally better than that of the Japanese, was of little help. While Manhattan Project scientists did anticipate that the bomb would release radiation, they assumed that anyone affected by it would be killed by the blast. Furthermore, as Stafford Warren would later explain, “The chief effort at Los Alamos was devoted to the design and fabrication of a successful atomic bomb. Scientists and engineers engaged in this effort were, understandably, so immersed in their own problems that it was difficult to persuade any of them even to speculate on what the after effects of the detonation might be” (107). Hymer Friedell, the deputy medical director at Oak Ridge, echoed these sentiments: “The idea was to explode the damned thing. . . . We weren’t terribly concerned with the radiation” (Malloy).

The American lack of understanding led General Leslie Groves to dismiss reports of radiation sickness as Japanese propaganda. In a September 1945 article in The New York Times, Groves stated, “The Japanese claim that people died from radiations [sic]. If this is true, the number was very small.” In November, Groves also testified before the Senate that radiation poisoning was “without undue suffering” and “a very pleasant way to die” (Southard 113).

Censorship

Almost immediately after the Japanese surrender, General Douglas MacArthur issued an occupation press code, restricting Japanese journalists from reporting on anything related to the bombings or the effects of radiation, and limiting foreign journalists. Official censorship would not be lifted until the end of the occupation in 1952. Additionally, the hibakusha were limited by their own self-censorship. Many felt shame because of their injuries and illness, guilt from the loss of loved ones, and, most of all, a desire to forget the past.

Nevertheless, news of the hibakusha began to spread. Australian journalist Wilfred Burchett, the first foreign journalist to visit Hiroshima after the bombings, sent his report by Morse code to London to avoid censorship. It was published in the London Daily Express, and was promptly distributed worldwide. American journalist and writer John Hersey also told the stories of six survivors in his book Hiroshima, originally published in The New Yorker in August 1946. It sold over a million copies worldwide within six months, but would be banned in Japan until 1949.

Over time, Japanese writers also began to tell the stories of the hibakusha. Doctor Takashi Nagai, a Nagasaki survivor, wrote Nagasaki no Kane (“The Bells of Nagasaki”) in 1949. Occupation officials insisted on the addition of an appendix, The Sack of Manila, with detailed information on Japanese atrocities in the Philippines in 1945. Nagai became known as the “saint of Nagasaki” for his writings and Christian faith before his eventual death from radiation poisoning in 1951.

In addition to written censorship, images of the bombings and their aftermath were strictly controlled. Documentary footage of Hiroshima and Nagasaki shot by a 32-man Japanese crew was confiscated by the United States in 1946. Some of the first depictions of the bombings in Japan were therefore not photographs but drawings. Toshi and Ira Maruki, who were not at Hiroshima but rushed there soon after to find their relatives, published their collection of drawings, Pika-don (“Flash-bang”), in 1950.

The Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission

Japanese medical research into the effects of radiation was also strictly controlled by occupation forces. The only sanctioned research was American: the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission (ABCC).

At the time of the bombing, very little was known about the long-term effects of radiation, which could affect a person’s health decades after the bombing. In June 1946, Lewis Weed, the head of the National Research Council of the National Academy of Sciences, brought together a group of scientists to consider the possibility of a scientific study on the survivors of the atomic bomb. The scientists recommended a “detailed and long-range study of the biological and medical effects upon the human being,” asserting that it was “of the utmost importance to the United States and mankind in general” (Lindee 32). President Truman would formally establish the ABCC in 1947.

The ABCC was officially a collaboration between the American National Research Council and the Japanese National Institute of Health. The success of the Commission was dependent on Japanese cooperation, not only from Japanese physicians but from the hibakusha as well. It was evident from the beginning, however, that the doctors did not trust each other. As one American doctor stated, “Just the thought of what the Japanese would do if they had free unrestrained use of our data and what they might publish under the imprimatur of the ABCC gives me nightmares.” On the other side, Nagasaki doctor Nishimori Issei countered, “The ABCC’s way of doing research seemed to us full of secrets. We Japanese doctors thought it went against common sense. A doctor who finds something new while conducting research is obligated to make it public for the benefit of all human beings” (Southard 182).

While the Commission provided medical examinations, it did not provide medical care because its mission had a no-treatment mandate. In the 1940s, medical treatment for human subjects was uncommon in most scientific studies, and the ABCC considered diagnosis a form of treatment in and of itself. The Commission also claimed that it was protecting the economic security of local doctors, despite frequent urging from Japanese physicians to treat the survivors.

Furthermore, treatment would have violated occupation policy. Colonel Crawford Sams, head of the Public Health and Welfare Section, told ABCC officials that they had “no authority to request examinations, obtain specimens or do operations on Japanese patients” (Lindee 131). Treatment itself became a political issue because, in the public eye, treating the hibakusha could have constituted American atonement for the bombings.

Nevertheless, the policy was controversial within the ABCC, and in practice it was not strictly enforced. American physicians did sometimes treat the hibakusha, particularly when their work involved home visits or pediatrics. On the other hand, many of the hibakusha never received treatment, and were merely photographed and then sent home. Norman Cousins, an American activist, criticized the ABCC for the “strange spectacle of a man suffering from [radiation] sickness getting thousands of dollars’ worth of analysis but not one cent of treatment from the Commission” (Southard 184).

Needless to say, this approach angered the hibakusha. Many were also upset that the ABCC was conducting studies on the bodies of the deceased. In the end, the majority of victims were willing to participate and to allow autopsies of their loved ones because they hoped that the research would ultimately help their cause. Others, like Mineko Do-oh, remained more resistant: “I refused to cooperate because of the way I was treated. I felt like an object being kept alive for research – and my pride wouldn’t allow this to happen” (193).

The ABCC was officially disbanded in 1975. Some of its programs, such as the Life Span Study (established in 1958), were taken over by Japanese institutions and continue to track the lingering effects of radiation to this day.

Fighting Back

The end of censorship in 1952 brought a new opportunity for the hibakusha to tell their stories. Photographs of the bombings and its victims, such as those in Yosuke Yamahata’s Atomized Nagasaki, were finally published. Life magazine would also publish a series of photographs from the bombings in 1952, including some taken by Yamahata.

Nevertheless, the hibakusha faced discrimination in their own society. They were denied entrance to public baths, job opportunities, and even marriage due to their status. Children with visible injuries were taunted by their classmates. Koichi Wada later explained, “A lot of rumors circulated back then that the hibakusha were carriers of serious diseases or that if two survivors got married, they would have disabled children” (Southard 204). Because of this, hibakusha often tried to hide the fact that they were survivors of the atomic bomb. Sumiteru Taniguchi recalled wearing long-sleeved shirts year round: “I didn’t want people to see my scars. I didn’t want them to gawk at me with weird expressions on their faces” (209).

Hibakusha also suffered from the long-term effects of radiation exposure. Beginning in 1947, doctors began to notice a higher incidence of leukemia as well as other cancers. Most of the conditions that the hibakusha suffered from were not covered under Japanese health care laws, while the terms of the 1951 San Francisco Peace Treaty prevented them from suing the United States for damages.

A legal movement to provide governmental support for the hibakusha began, as well as fundraising campaigns to support the victims. The 1957 Atomic Bomb Victims Medical Care Law eventually provided some benefits, but there were stringent requirements including proof of location at the time of the bombing, which was very difficult to obtain. The Hibakusha Relief Law, passed in 1995, was more comprehensive and officially defined the hibakusha as those who were within two kilometers of the blasts or visited the bombing sites within two weeks. By this definition, there was more than a million hibakusha at the end of the war. Nevertheless, as Taniguchi explained, “The law is very hard to understand, and the procedures for applying for and receiving support from the government are very complicated” (300).

Despite discrimination, the hibakusha slowly found ways to rebuild their lives. They petitioned the American government for the confiscated video footage of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and it was eventually released in 1967. They also petitioned for the return of the hibakusha autopsy specimens during the 1960s, and the ABCC ultimately agreed.

As the Japanese scientific community became more established after the war, the Radiation Effects Research Foundation (RERF) was created to calculate exact dose estimates of the survivors. The Atomic Bomb Disease Institute was also established at Nagasaki University.

Perhaps most importantly, the hibakusha became more comfortable publicly expressing their experiences, and many found a new purpose in doing so. Taniguchi went on a speaking tour, explaining that he owed it to the “hundreds of thousands of people who wanted to say what I’m saying, but who died without being able to” (250).

To this end, one of the most important cultural products of the period was Keiji Nakazawa’s comic Barefoot Gen, originally published in 1972 and 1973 in the weekly magazine Shonen Jump. Nakazawa survived the bombing of Hiroshima and lost most of his family when he was six years old. Barefoot Gen is thus semi-autobiographical, and tells the story of Hiroshima from the prewar era to the aftermath of the bombing. In the end, Gen, the hero, leaves Hiroshima to go to Tokyo and become a professional cartoonist, declaring “I’ll go on living whatever it takes! I promise.” Unlike other hibakusha works, Barefoot Gen shows issues such as Japanese propaganda and restrictions on freedoms as well as postwar discrimination against the hibakusha. As Nakazawa later recalled, “It was the first time people had heard the truth. That’s what they told me everywhere I went” (Szasz 114).

The Anti-Nuclear Movement

Since the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan has been a world leader in the anti-nuclear movement. This movement was also prompted in part by American hydrogen bomb tests in the Marshall Islands in 1954. During the Castle Bravo test, the largest ever conducted by the United States, fallout reached a Japanese fishing boat named Daigo Fukuryū Maru or “Fifth Lucky Dragon,” located 80 miles east of the test site. All 23 members of the crew, as well as their catch, were exposed to radiation. One crewmember died several months later, although the cause of his death remains disputed.

Since the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan has been a world leader in the anti-nuclear movement. This movement was also prompted in part by American hydrogen bomb tests in the Marshall Islands in 1954. During the Castle Bravo test, the largest ever conducted by the United States, fallout reached a Japanese fishing boat named Daigo Fukuryū Maru or “Fifth Lucky Dragon,” located 80 miles east of the test site. All 23 members of the crew, as well as their catch, were exposed to radiation. One crewmember died several months later, although the cause of his death remains disputed.

The Lucky Dragon incident prompted outrage across Japan. Hiroshima mayor Shinzo Hamai declared that humans were facing “the possibility of self-extinction” and needed “total abolition of war and for the proper control of nuclear energy throughout the world” (Hogan 181). A group of Tokyo housewives started a petition to ban nuclear weapons worldwide, collecting an extraordinary 32 million signatures, roughly a third of Japan’s population at the time. The Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission’s offer of free treatment to the Lucky Dragon crew in exchange for participation in the radiation study also set off an uproar among the hibakusha, who saw this as proof that that the ABCC was using them as guinea pigs.

The anti-nuclear movement even found its way into Japanese popular culture. In 1954, producer Tomoyuki Tanaka imagined, “What if a dinosaur sleeping in the Southern Hemisphere had been awakened and transformed into a giant by the Bomb? What if it attacked Tokyo?” (Tsutsui 15). The result was Godzilla, or Gojira in Japanese. As Tanaka would explain, “The theme of the film, from the beginning, was the terror of the Bomb. Mankind had created the Bomb, and now nature was going to take revenge on mankind” (18).

Movements for peace also began, such as the “peace declaration” read by the mayor of Nagasaki on the anniversary of the bombing every year since 1954. The Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park and Hall and the Nagasaki Peace Statue and Peace Park were opened in 1955. In 2015, the Hiroshima site received 1.5 million visitors, including more than 300,000 foreigners.

In 1955, Hiroshima also organized the First World Conference Against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs. Members of the hibakusha spoke at the second conference, held in Nagasaki in 1956, and press coverage of the event amplified their voices.

Victim Consciousness

Although the suffering of the hibakusha is without a doubt unique to them, higaisha ishiki (“victim consciousness”) quickly took a central role in Japan’s collective national identity. This was foreshadowed and perhaps started by Emperor Hirohito in his radio speech announcing Japan’s surrender on August 15, 1945: “The enemy has begun to employ a new and most cruel bomb, the power of which to damage is indeed incalculable, taking the toll of many innocent lives. Should we continue to fight, it would not only result in an ultimate collapse and obliteration of the Japanese nation, but also it would lead to the total extinction of human civilization.”

While Germany in large part confronted and, from a national identity perspective, dealt with its crimes during World War II, Japan did not go through the same process. In establishing its post-war identity, Japan focused on the suffering of the atomic bombings rather than the atrocities it committed in the years leading up to and during the war. Japanese brutality included the invasion of Manchuria, where the infamous “Unit 731” conducted human medical experiments, POWs were used for slave labor, and thousands of women were forced into sexual slavery as “comfort women” for the Japanese Army. Equally brutal was the invasion of the Philippines, where the Bataan Death March saw the deaths of thousands of American and Filipino POWs.

The Tokyo Trials of Japanese war criminals lasted almost three times as long as those in Nuremberg, and all 25 “Class A” defendants were found guilty. The United States made use of mass media during the occupation to spread the news of Japanese war crimes, but it did not take root. While many Japanese were shocked to learn of the atrocities their army had committed, they also viewed all soldiers who saw combat as “victims” of the war and many believed the war to be legitimate self-defense.

The victim narrative persisted in large part because of political conservatism in the Japanese government under the Liberal Democratic Party. Historian John W. Dower described how “nuclear victimization spawned new forms of nationalism in postwar Japan – a neonationalism that coexists in complex ways with antimilitarism and even the ‘one-country pacifism’ long espoused by many individuals and groups associated with the political Left” (Hogan 124).

Victim consciousness was reflected, for example, in history textbooks which often shortened or completely left out Japan’s role in the war. Even the National Showa Memorial Museum, opened in 1999 in Tokyo, played down Japanese atrocities and was instead established “to commemorate Japanese suffering during and after World War II.”

Perceptions of the Hibakusha in the United States

For the most part, early reactions in the United States to the bombings were triumphant. Censorship meant that few stories of the survivors reached the United States. Government personnel, such as Secretary of War Henry Stimson in his article “The Decision to Use the Atomic Bomb,” defended the bombings, and it had a marked effect on public perception. As physicist Eugene Rabinowitch wrote in 1956, “With few exceptions, public opinion rejoiced over Hiroshima and Nagasaki as demonstrations of American technical ingenuity and military ascendency.”

Over time, however, the American public gained a better understanding of the experiences of the survivors. In 1955, the hibakusha were brought to national attention when a group of 25 women (dubbed the “Hiroshima Maidens”) came to the United States for reconstructive surgery. The project had its origins with Kiyoshi Tanimoto, a Methodist minister who was one of the six hibakusha featured in John Hersey’s Hiroshima. Tanimoto sought to help the women, who suffered from extreme deformities as a result of their injuries, but plastic surgery in Japan at the time was not as advanced as in the United States. Tanimoto enlisted the help of magazine editor and activist Norman Cousins. Over the objections of the State Department, which feared that the surgeries could constitute an admission of American guilt, the Maidens came to New York City. 138 operations were performed over 18 months at Mount Sinai Hospital with mixed results; one of the women died of cardiac arrest.

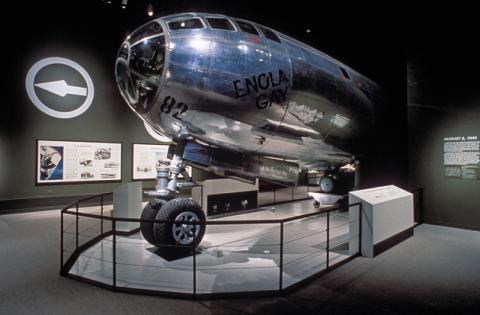

Tanimoto was featured along with the two of the Maidens on an episode of This is Your Life in May 1955. Without informing his guests in advance, host Ralph Edwards arranged for Captain Robert Lewis, the co-pilot of the Enola Gay, to appear as well. An ashen-faced Tanimoto shook hands with Lewis, who appeared overcome with emotion. (It was later reported that Lewis was in fact drunk – upon hearing that he would be appearing with victims of the bombings, he was so distraught that he headed straight for the bar.)

Following the visit of the Hiroshima Maidens, a new wave of literature and film on the bombings appeared in the United States. “Nuclear War in St. Louis,” written by anti-nuclear activists in St. Louis, was republished in Cousins’ Saturday Review in 1959. Betty Jean Lifton produced A Thousand Cranes, a documentary on children survivors, in 1970. Her husband, physician Robert Jay Lifton, also published Death in Life: Survivors of Hiroshima in 1967, featuring accounts from 70 hibakusha. As Robert Lifton later explained, “We require Hiroshima and its images to give substance to our own terrors… They have kept alive our imagination of holocaust and, perhaps, helped to keep us alive as well” (Hogan 160).

Nevertheless, the memory politics associated with the bombings remained controversial in the United States, just as they did in Japan. In 1995, a proposed Enola Gay exhibit at the National Air and Space Museum was canceled after protests from military veterans as well as heavy criticism from the media, historians, and even Congress. The exhibit had planned to show hibakusha testimonies and photographs, as well as a section on Japanese wartime atrocities.

Legacy

The effects of the atomic bombings of Japan continue to the present day. The very word “Hiroshima,” in Japan and in the United States, conjures images of the horrors of nuclear weapons and modern warfare. Historians, scientists, and politicians continue to debate the moral and strategic justifications of the bombings.

In 2011, the Fukushima Daiichi plant accident in Japan caused the worst nuclear meltdown since Chernobyl. It also prompted a major shift in the Japanese anti-nuclear movement toward protests against nuclear power, and the Japanese government is currently moving to phase out nuclear power plants completely. Victims of the accident are also called hibakusha. (Although the word uses slightly different characters than that of atomic bomb victims, in this case meaning “victims of radiation from a nuclear accident,” the two are pronounced the same.) A 2017 survey reported that 62% of the 348 Fukushima hibakusha who were interviewed have experienced discrimination.

Although in recent years Japan’s narrative stemming from victim consciousness has softened somewhat, it still exists. During his visit to Pearl Harbor in 2016, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe spoke of “the spirit of tolerance and the power of reconciliation” and offered his “sincere and everlasting condolences to the souls of those who lost their lives,” but made no apologies. Abe, a member of the Liberal Democratic Party, nevertheless faced political criticism in Japan for making the visit at all.

In May 2016, Barack Obama became the first U.S. president to visit Hiroshima. “We stand here in the middle of this city and force ourselves to imagine the moment the bomb fell,” he said. “We force ourselves to feel the dread of children confused by what they see. We listen to a silent cry. We remember all the innocents killed across the arc of that terrible war and the wars that came before and the wars that would follow.” Additionally, Obama called for limits on nuclear weapons, asserting, “We may not realize this goal in my lifetime, but persistent effort can roll back the possibility of catastrophe. We can chart a course that leads to the destruction of these stockpiles. We can stop the spread to new nations and secure deadly materials from fanatics.”

Obama also added two paper cranes to a memorial to Sadako Sasaki. Two years old at the time of the bombing, Sasaki became famous for folding paper cranes because of a Japanese legend that anyone who folds 1000 cranes will be granted a wish. She died from leukemia in 1955, and inspired the 1977 children’s book Sadako and the 1000 Paper Cranes. Today, paper cranes carry a symbolic importance for Japan. The Sadako Legacy, a nonprofit organization dedicated to carrying on Sasaki’s message, has donated her cranes to memorials around the world, including the World Trade Center and Pearl Harbor.

As of 2016, an estimated 174,000 hibakusha remain alive today. They and their descendants still face discrimination in Japan, particularly with marriage. Many continue to conceal the truth of their history and the suffering that their families endured.