Updated April 3, 2019.

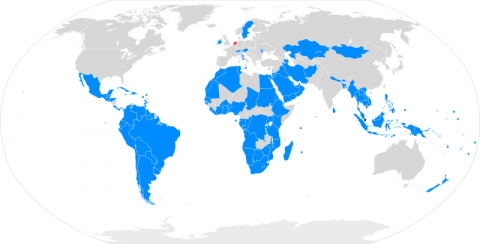

On July 7, 2017, the United Nations passed Resolution 71/258, or the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW). 122 nations adopted this ambitious treaty to prohibit the development, testing, production, manufacturing, acquisition, and possession of nuclear weapons and nuclear explosives.[1] After it passed, initially 23 countries signed the treaty when it was first opened for signature on September 20, 2017. Since then, 47 additional countries have signed the treaty.[2]

Notably and unsurprisingly, the countries that did not sign the TPNW are countries with nuclear weapons. The 5 nuclear states that are party to the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) which are the United States, Russia, China, the United Kingdom, and France, and the nuclear states outside of the NPT (India, Pakistan, Israel, and North Korea), boycotted the vote. As well, countries under the US nuclear umbrella did not vote. For example, Japan, South Korea, and NATO members do not possess nuclear weapons but they are under the protection of the United States through extended deterrence.

The TPNW will not enter into force until at least 50 countries have ratified it. While 70 countries have signed the treaty and thus indicated that they accept it and promise not to undermine it, these signatures are not legally binding. Ratification is legally binding because the treaty must be adopted by the countries’ legislatures and therefore become part of those countries’ laws.[3] As of February 2019, only 22 countries have ratified the TPNW and became state parties to the treaty, including Austria, Costa Rica, Mexico, and New Zealand.[4] This means that the treaty does not yet have legal force and effect.[5] The TPNW will enter into force 90 days after 50 countries ratify it.

The Humanitarian Initiative

The TPNW has its roots in the Humanitarian Initiative, which is “a continuation of the decades-long drive to advance nuclear disarmament through legal means” and aims to “‘[fill] the legal gap’ on the use of nuclear weapons and advancing the nuclear disarmament agenda.”[6] Countries that support the Initiative have pointed to three core arguments for prohibiting nuclear weapons:[7]

1. There have been too many “close calls” that almost resulted in the use of nuclear weapons.

2. The humanitarian and environmental impacts of a nuclear detonation would be catastrophic, and no nation has the capacity to respond to such a situation.

3. The use of nuclear weapons would inherently violate the idea of just wars and, in particular, Jus in Bello (Latin for “right in war”), which refers to the actions of parties in armed conflicts.[8] The theory of just wars states that for a country to act morally in a war or conflict, it must follow the principles of discrimination (only attacking combatants and not attacking innocent, nonmilitary civilians), proportionality (a country’s force used in war must be proportional to the country’s adversary’s use of force), and responsibility (ensuring that all actions are carried out with the intention of producing only good impacts, negative impacts of action are not intended, and “the good of the war must outweigh the damage done by it”).[9]

The inception of the Humanitarian Initiative began after the 2010 UN NPT Review Conference. The 2010 Review Conference stated in the final document that:

“The Conference expresses its deep concern at the catastrophic humanitarian consequences of any use of nuclear weapons and reaffirms the need for all States at all times to comply with applicable international law, including international humanitarian law.”[10]

This was the first time that the humanitarian consequences of nuclear weapons have been taken into consideration during an NPT Review Conference.

From 2013 to 2014, three inter-governmental conferences were held in Norway, Mexico, and Austria about the humanitarian consequences of nuclear weapons. As well, NGOs had the opportunity to bring in civil society’s perspective on nuclear issues and played an instrumental role in these conferences. The most prominent NGO was the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN). The December 2014 Vienna Conference resulted in the Humanitarian Pledge, which “[r]ecogniz[ed] the complexity of and interrelationship between these consequences [of nuclear weapons] on health, environment, infrastructure, food security, climate, development, social cohesion and the global economy that are systemic and potentially irreversible.”[11]

At the 2015 NPT Review Conference, Switzerland, on behalf of 16 other countries, delivered a joint statement about the “humanitarian consequences” and the “immeasurable suffering” a nuclear explosion would bring. The statement concludes that “[a]ll States must intensify their efforts to outlaw nuclear weapons and achieve a world free of nuclear weapons.”[12] Eventually, a total of 159 countries signed onto this declaration.[13]

In 2016, a special UN working group was convened to discuss the possibility of nuclear disarmament. In August of that year, the group focused on the legal frameworks surrounding nuclear weapons and later proposed that negotiations for a treaty prohibiting nuclear weapons should take place. This proposition eventually led to the December 2016 UN General Assembly Resolution 71/258, or the TPNW.[14]

Nuclear Weapons States and the Vienna Conference

For the first time in December 2014, nuclear-weapon states that are party to the NPT attended the conference on the Humanitarian Impact of Nuclear Weapons: The United States and the United Kingdom. China, also an NPT member, sent an unofficial representative. India and Pakistan, two nuclear-weapon states that are not part of the NPT, were also present and had attended previous conferences.[15] The agenda of this Vienna Conference focused on “the risk of nuclear weapons use, the application of international law to the consequences of nuclear weapons explosions, and the shortfalls in international capacity to address a humanitarian emergency caused by the use of nuclear weapons.”[16]

Austria, in its address, stated that nuclear-weapon states in the NPT needed to “identify and pursue effective measures to fill the legal gap for the prohibition and elimination of nuclear weapons” and promised “to cooperate with all stakeholders to achieve this goal.”[17] The United States agreed with this sentiment, but added the caveat that there needs to be “a practical way to do it.”[18] The other four nuclear-weapon states in the NPT concurred that there are “serious consequences of nuclear weapon use” but also advocated for “the practical, step-by-step approach [the United States, the United Kingdom, France, Russia, and China] are taking has proven to be the most effective means to increase stability and reduce nuclear dangers.”[19]

The conference concluded that there was a legal gap with regards to nuclear weapons and called for a complete and immediate ban on nuclear weapons.[20] This, of course, stood in contradiction of the calls for “the practical, step-by-step approach” to nuclear disarmament. Traditionally, the step-by-step approach took the form of arms control treaties between the United States and Russia. From the end of the Cold War to today, the number of nuclear weapons dropped from over 57,000 weapons to 9,100 between the two countries as a result of these treaties.[21] Since then, however, nuclear arms reduction has slowed down, a situation many non-nuclear weapon states have expressed displeasure with. Furthermore, Washington and Moscow continue their modernization programs, which extend the lives of aging weapons.

Because of this diverging point of view on how to disarm, the United States, the United Kingdom, France, Russia, and China eventually boycotted the UN Working Group that worked on the TPNW and the vote on the TPNW. Allies under the protection of the U.S. nuclear umbrella did the same.

Role of Nongovernmental Organizations

One of the most notable aspects of the TPNW is the role that nongovernmental organizations and civil society played in the writing and eventual adoption of the treaty by the UN. ICAN, a nongovernmental organization that is committed to the prohibition of nuclear weapons, was one of the most prominent organizations in lobbying for the treaty. For its work, the Nobel Committee awarded ICAN the Nobel Peace Prize in 2017, citing “its work to draw attention to the catastrophic humanitarian consequences of any use of nuclear weapons and for its ground-breaking efforts to achieve a treaty-based prohibition of such weapons.”[22]

Other NGOs involved in advocating for a ban on nuclear weapons include the International Committee of the Red Cross and the Red Crescent, the International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War, and the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom.

Strengths of TPNW

The TPNW has two notable strengths. First, it “democratized” nuclear weapons issues. Second, it focused on the humanitarian impacts of nuclear weapons by highlighting the stories of survivors.

The conferences leading up to the treaty and the UN negotiations made nuclear weapons issues more democratic on two fronts. First, non-nuclear weapon states, such as Norway, Austria, Switzerland, Mexico, and Brazil, had the opportunity to take the lead on writing and negotiating a UN resolution related to nuclear weapons. Second, civil society played a huge role in the TPNW’s adoption. Traditionally, nuclear weapons states have taken the lead and almost monopolized the conversation surrounding nuclear weapons. This started with the failed Baruch Plan (1946), introduced by the United States, to completely eliminate the atomic bomb. This democratization demonstrated that concerns around nuclear weapons are not only limited to states that possess them.

Another strength is that the TPNW specifically puts front and center the victims of nuclear weapons and nuclear weapons testing. By doing so, the Humanitarian Initiative was reminding everyone about the real costs and consequences of nuclear weapons. During the conferences, survivors had the opportunity to share their stories. For example, Setsuko Thurlow, a hibakusha (atomic bomb survivor) from Hiroshima, has been a leader in ICAN and has shared her story to make real the consequences of nuclear weapons.[23] As well, Indigenous communities in Australia had the opportunity to present their statement before the UN about the impacts of British tests on their community, health, and culture.[24] While the Limited Test Ban Treaty of 1963 was, in part, a response to the Castle Bravo test, which resulted in the Daigo Fukuryu Maru Incident and the Marshallese being exposed to radioactive fallout, the language of the LTBT itself does not address the humanitarian impacts of atmospheric testing.

Limitations of TPNW

The TPNW faces crucial limitations that must be addressed in order to ensure its success. The most notable problem is verification, which typically refers to “technical means and measures designed to ensure that a country is following the terms of the treaty and that it is not liable to engage in deception or outright cheating in an attempt to circumvent the spirit and the letter of the agreement.”[25]

Many practitioners and arms control scholars have noted that verification is the “most crucial but also the most difficult to negotiate.”[26] Verification is critical, because it establishes trust among countries and ensures that all parties are compliant with the treaty they signed. However, when a country is willing to undergo a verification process as part of its treaty obligations, that country must be willing to give up a certain level of secrecy and privacy. A verification process that reveals too much information may put that country’s security at risk. For that reason, negotiating verification procedures is the most difficult part.

Unlike the Chemical Weapons Convention of 1993, the TPNW does not include a verification or compliance regime to ensure that a nuclear weapons state is in compliance with its obligations to eliminate its nuclear stockpile. Beyond mentioning that an international organization would oversee the dismantlement and disarmament verification of nuclear weapons,[27] it does not outline the duties and responsibilities of said organization, nor does it detail the types of verification procedures a nuclear weapons state would have to undergo (e.g., on-site inspections).

As part of the TPNW, state parties must also be in compliance with the International Atomic Energy Association (IAEA) Safeguards Agreement. The Safeguards Agreement allow the IAEA to verify that a country with a nuclear energy program is not using its energy program for nuclear-weapons purposes and that the country is upholding its nonproliferation commitments.[28]However, the IAEA strictly deals with the issues of nuclear energy and therefore cannot oversee the dismantlement and disarmament of nuclear weapons.

As Dr. Jürgen Scheffran, a physicist and professor of geography at the University of Hamburg, Germany, states:

“To be effective, the TPNW needs to be adequately verified to build confidence, assure compliance of the State Parties and provide timely warning of non-compliance. Preconditions in the verification process are to define the goals, indicated by legal requirements regarding treaty-limited items and activities, and to identify the means to monitor states and activities. Goals and means of verification need to be balanced in terms of its benefits, costs and risks. The question is whether an intolerable deviation from treaty, limited items, and activities can be detected with reasonable efforts.”[29]

Future of the TPNW

The TPNW is not, by any means, immutable. Like other treaties, it can be amended to improve its effectiveness.

Dr. Scheffran suggests an adaptive approach to amending the TPNW and outlines three basic points that future amendments should include. First is preventing party states from accessing “any nuclear weapons, nuclear materials or other components relevant for a nuclear weapons capability.”[30] To accomplish this, states parties would participate in information exchanges and data gathering, which include but are not limited to declarations, on-site inspections, and remote monitoring.[31] Second is detecting illicit nuclear activities and preventing the (re)armament of state parties. Third is to create plans that include the “active dismantlement of nuclear weapons, disposal of nuclear materials, and the conversion or destruction of nuclear facilities.”[32]

Dr. Scheffran ends his recommendations by pointing out the importance that the current political climate and the relationships with other nations play in countries’ acquisition of –and decision to keep–nuclear weapons. He proposes that there should be an implementation of political, organizational, and societal mechanisms outside of the treaty to bolster verification and trust-building measures to reduce the incentives for a country to acquire a nuclear weapon. These mechanisms include bringing the general public into conversations about nuclear issues through education and discourse and improving international conflict-resolution procedures to resolve problems among countries before they become armed conflicts. [33]

Tamara Patton, a PhD Student at the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, suggests her own potential amendments to the TPNW, which would also address the problems surrounding verification. She proposes developing an “of an international monitoring system for nuclear disarmament and nonproliferation verification (NDN-IMS).”[34] The purpose of such a system would be to monitor state parties’ compliance with the TPNW, coordinate research to develop technologies that improve verification methods, and increase the warning time for the international community if a country decides to restart its nuclear weapons program after becoming a party to the TPNW. [35]

Conclusion

In the short term, the TPNW remains controversial in its success in prohibiting nuclear weapons. The treaty continues to gain support from states that do not possess nuclear weapons. However, countries that have nuclear weapons argue that they need those weapons to protect themselves against hostile nations and guard against an uncertain future. However, if comprehensive verification measures are included and relations among countries improve, the TPNW may be foundational in the process of disarming and dismantling nuclear weapons globally in the future.

[1] “Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons” (UN Resolution, New York City, 2017 https://www.un.org/disarmament/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/tpnw-info-kit-v2.pdf), 12.

[2] Signature/ratification status of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons,” ICAN, accessed March 20, 2019, http://www.icanw.org/status-of-the-treaty-on-the-prohibition-of-nuclear-weapons/.

[3] “What is the CTBT?” CTBTO, accessed March 25, 2019, https://www.ctbto.org/the-treaty/article-xiv-conferences/2011/afc11-information-for-media-and-press/what-is-the-ctbt/.

[4] Signature/ratification status of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons,” ICAN, accessed March 20, 2019, http://www.icanw.org/status-of-the-treaty-on-the-prohibition-of-nuclear-weapons/.

[5] “Glossary,” United Nations Treaty Collection, accessed March 20, 2019, https://treaties.un.org/pages/overview.aspx?path=overview/glossary/page1_en.xml.

[6] Michal Onderco, “Why nuclear weapon ban treaty is unlikely to fulfill its promise,” Global Affairs 3, no. 4-5 (2017): 391.

[7] Ibid., 392.

[8] “What are jus ad bellum and jus in bello?” ICRC, published January 22, 2015, https://www.icrc.org/en/document/what-are-jus-ad-bellum-and-jus-bello-0.

[9] “Just War Theory,” Oregon State, accessed March 20, 2019, https://oregonstate.edu/instruct/phl201/modules/just_war_theory/criteria_intro.html.

[10] “Final Document” (2010 Review Conference of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, New York City, 2010, https://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=NPT/CONF.2010/50%20%28VOL.I%29), 19.

[11] “Humanitarian Pledge” (Statement, Vienna Conference, Vienna, 2014, http://www.icanw.org/campaign/humanitarian-initiative/).

[12] “Joint Statement on the humanitarian dimension of nuclear disarmament by Austria, Chile, Costa Rica, Denmark, Holy See, Egypt, Indonesia, Ireland, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Nigeria, Norway, Philippines, South Africa, Switzerland” (Joint Statement, First Session of the Preparatory Committee for the 2015 Review Conference of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, New York City, 2015, http://www.reachingcriticalwill.org/images/documents/Disarmament-fora/npt/prepcom12/statements/2May_IHL.pdf).

[13] “Humanitarian Initiative,” ICAN, accessed March 20, 2019, http://www.icanw.org/campaign/humanitarian-initiative/.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Kingston Reif, “Nuclear Impact Meeting is Largest Yet,” Arms Control Association, published January/February 2015, https://www.armscontrol.org/ACT/2015_0102/News/Nuclear-Impact-Meeting-Is-Largest-Yet.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Rebecca Davis Gibbons, “The humanitarian turn in nuclear disarmament

and the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons,” The Nonproliferation Review 25 (2018):1-2, 11-36.

[20] “A Pledge To Fill The Legal Gap,” (Vienna Report, Vienna, 2014, http://www.icanw.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/ViennaReport.pdf): 2.

[21] David Wright, “Arms control successes,” Union of Concerned Scientists, published December 17, 2014, https://blog.ucsusa.org/david-wright/nuclear-weapons-end-of-the-cold-war-769.

[22] “The Nobel Peace Prize for 2017,” The Nobel Prize, accessed March 22, 2019, https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/peace/2017/press-release/.

[23] “Setsuko Thurlow,” ICAN, accessed March 25, 2019, http://www.icanw.org/setsuko-thurlow/.

[24] “Indigenous Statement to the U.N. Nuclear Weapons Ban Treaty Negotiations,” ICAN, accessed March 25, 2019, http://www.icanw.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Indigenous-Statement-June-2017.pdf.

[25] Craig R. Wuest, “The Challenge for Arms Control Verification in the Post-New START World,” (Report, Washington, DC, 2012, https://www.ipndv.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/Wuest_2012_The_Challenge_for_Arms_Control_Verification_in_the_Post_New_START_World.pdf): 2.

[26] Michal Onderco, “Why nuclear weapon ban treaty is unlikely to fulfill its promise,” Global Affairs 3, no. 4-5 (2017): 394.

[27] Ibid.

[28] “Basics of IAEA Safeguards,” IAEA, accessed March 25, 2019, https://www.iaea.org/topics/basics-of-iaea-safeguards.

[29] Jurgen Scheffran, “Verification and security of transformation to a nuclear weapon-free world: the framework of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons,” Global Change, Peace & Security 30, no. 2 (2018): 145.

[30] Jurgen Scheffran, “Verification and security of transformation to a nuclear weapon-free world: the framework of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons,” Global Change, Peace & Security 30, no. 2 (2018): 147.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Tamara Patton, “An international monitoring system for verification to

support both the treaty on the prohibition of nuclear weapons and the nonproliferation treaty,” Global

Change, Peace & Security 30, no.2 (2018): 190.

[35] Ibid.