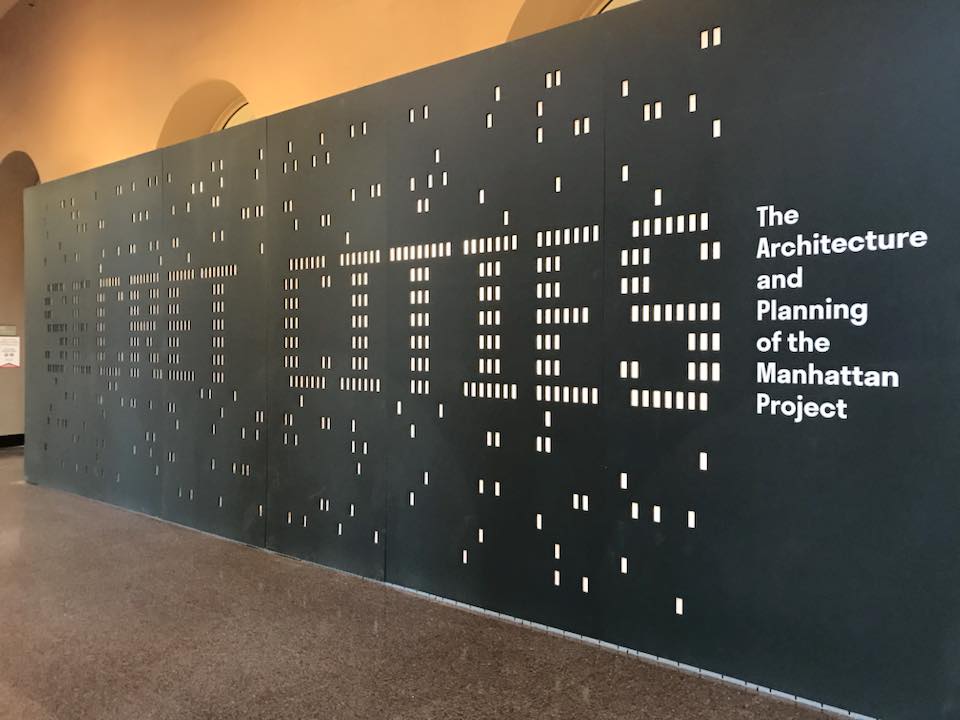

On May 3, a new exhibition, “Secret Cities: The Architecture and Planning of the Manhattan Project,” opened at the National Building Museum in Washington, DC. “Secret Cities” explores architecture and daily life at Hanford, WA, Los Alamos, NM, and Oak Ridge, TN during the Manhattan Project. AHF served as an advisor for the exhibition. The exhibition features excerpts from several AHF oral history interviews that recount life in these communities during World War II.

Martin Moeller, the National Building Museum’s senior curator, explains, “The Manhattan Project was one of the most complicated endeavors in history. While its scientific, military, and political importance have been widely recognized, less well known is its significance in the history of architecture, engineering, and planning. This exhibition explores how the three new cities built for the Manhattan Project served as proving grounds for emerging ideas about buildings and communities. The exhibition also tells the very human story of the unique cultures that developed in these places, illuminated in part through several oral histories provided by the Atomic Heritage Foundation.”

“Secret Cities” begins by highlighting early twentieth-century discoveries about radiation and radioactivity. It traces the development of the Bauhaus and other modernist schools of architecture, as well as the work of the architectural firm Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, which would become the primary architecture and planning contractor for Oak Ridge.

The exhibition then discusses the famous Einstein-Szilard Letter and the entry of the United States into World War II in 1941. Fearing they were in a race against Nazi Germany to build an atomic weapon, Manhattan Project officials, under the leadership of General Leslie Groves, expropriated large swathes of land in three states to build a top-secret weapons laboratory and production facilities. In the areas of Los Alamos, Hanford, and Oak Ridge, local residents, including farmers and Native American communities, were evicted from their lands, often with minimal compensation.

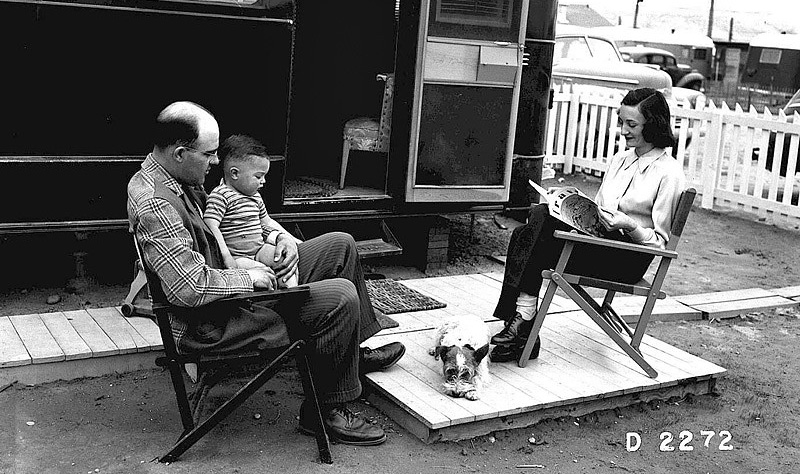

Fueled by wartime urgency, construction proceeded rapidly at each site. Yet the planners of the “Secret Cities” realized the importance of creating communities where employees would want to live and work. Bill Wilcox, who arrived in Oak Ridge in 1943, remembered, “Groves realized that it was important to have the feeling of a community where these scientists and engineers and top managers and their spouses and their children would feel at home, not like they were just off in a terribly temporary community. He wanted it to have the feel of a normal town.” Wilcox described the building of neighborhood schools and shopping centers, and why he felt Oak Ridge was a “remarkable place.”

Fueled by wartime urgency, construction proceeded rapidly at each site. Yet the planners of the “Secret Cities” realized the importance of creating communities where employees would want to live and work. Bill Wilcox, who arrived in Oak Ridge in 1943, remembered, “Groves realized that it was important to have the feeling of a community where these scientists and engineers and top managers and their spouses and their children would feel at home, not like they were just off in a terribly temporary community. He wanted it to have the feel of a normal town.” Wilcox described the building of neighborhood schools and shopping centers, and why he felt Oak Ridge was a “remarkable place.”

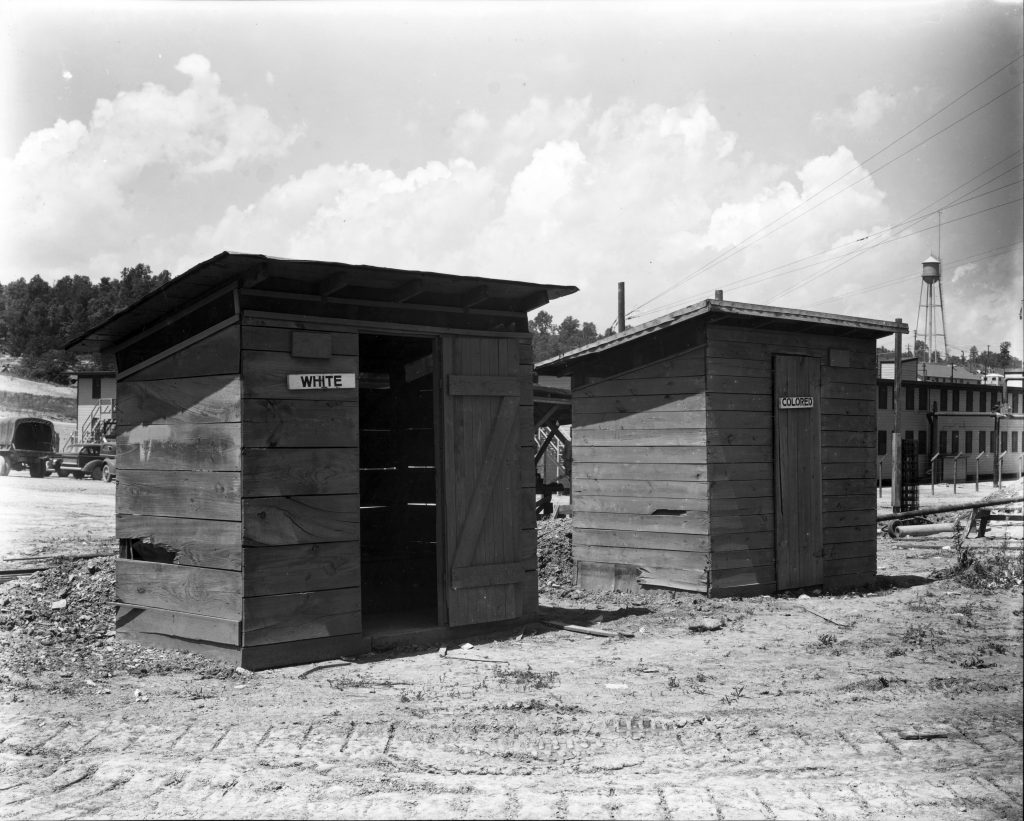

However, as the exhibition details, segregation was designed into the new communities from the beginning. At Oak Ridge, housing was segregated; African-Americans were forced to use separate restrooms, drinking fountains, and dining and recreational facilities. At Hanford, housing was also segregated. Just one of the nearby Tri-Cities, Pasco, allowed African-American residents.

In addition to working with potentially dangerous materials, Manhattan Project employees had to deal with other hardships in the new communities, from the omnipresent mud at Los Alamos and Oak Ridge to the desert dust storms at Hanford. Hanford worker Steve Buckingham remembered, “The recruiting posters were really funny. ‘Come to the evergreen state of Washington. Sparkling rivers. Snow-capped peaks. Wonderful fishing and hunting.’ What do they come to? They come to a desert.”

As its title suggests, the exhibition also explores the efforts at each site to keep the top-secret work hidden from the outside world. Author Jennet Conant mentions the security measures at Los Alamos: “The secrecy was so intense. The guards, the barbed wire; passes, all the precautions that were taken. They had hundreds of FBI agents, G-2 men stationed all around Albuquerque and Santa Fe. It was crawling with FBI. So the security precautions were enormous.” Despite these efforts, physicist Klaus Fuchs and other spies managed to pass atomic secrets to the Soviet Union.

As they enter the final room of the exhibition, visitors walk past a video of J. Robert Oppenheimer’s famous quotation from the Bhagavad Gita. The exhibition describes the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, featuring photographs of the devastation and reflections from veterans and survivors. “Secret Cities” concludes with sections on the growth of Oak Ridge, Hanford, and Los Alamos since World War II, atomic culture, and the creation of the Manhattan Project National Historical Park in 2015.

As they enter the final room of the exhibition, visitors walk past a video of J. Robert Oppenheimer’s famous quotation from the Bhagavad Gita. The exhibition describes the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, featuring photographs of the devastation and reflections from veterans and survivors. “Secret Cities” concludes with sections on the growth of Oak Ridge, Hanford, and Los Alamos since World War II, atomic culture, and the creation of the Manhattan Project National Historical Park in 2015.

The exhibition notes how the three communities have continued to influence American life since World War II. Los Alamos, Hanford, and Oak Ridge provided early models for postwar suburban development. Today, each site continues to work in areas such as national security, environmental cleanup, and renewable energy – some of the most pressing issues facing the United States in the 21st century.

“Secret Cities” provides a thought-provoking look at the Manhattan Project’s legacies for architecture, planning, engineering, and design. AHF highly recommends it to visitors and Washington, DC residents. The exhibition will be open through March 3, 2019.

For more information about the exhibition, visit the Building Museum’s website. “Secret Cities” was recently featured in The Guardian and Atlas Obscura. You can watch the full interviews with Bill Wilcox, Steve Buckingham, Jennet Conant, and many others on the “Voices of the Manhattan Project” website.